The Land of Lorne;

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Anne R Johnston Phd Thesis

;<>?3 ?3@@8393;@ 6; @53 6;;3> 530>623? 1/# *%%"&(%%- B6@5 ?=316/8 >343>3;13 @< @53 6?8/;2? <4 9A88! 1<88 /;2 @6>33 /OOG ># 7PJOSTPO / @JGSKS ?UDNKTTGF HPR TJG 2GIRGG PH =J2 CT TJG AOKVGRSKTY PH ?T# /OFRGWS &++& 4UMM NGTCFCTC HPR TJKS KTGN KS CVCKMCDMG KO >GSGCREJ.?T/OFRGWS,4UMM@GXT CT, JTTQ,$$RGSGCREJ"RGQPSKTPRY#ST"COFRGWS#CE#UL$ =MGCSG USG TJKS KFGOTKHKGR TP EKTG PR MKOL TP TJKS KTGN, JTTQ,$$JFM#JCOFMG#OGT$&%%'($'+)% @JKS KTGN KS QRPTGETGF DY PRKIKOCM EPQYRKIJT Norse settlement in the Inner Hebrides ca 800-1300 with special reference to the islands of Mull, Coll and Tiree A thesis presented for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Anne R Johnston Department of Mediaeval History University of St Andrews November 1990 IVDR E A" ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS None of this work would have been possible without the award of a studentship from the University of &Andrews. I am also grateful to the British Council for granting me a scholarship which enabled me to study at the Institute of History, University of Oslo and to the Norwegian Ministry of Foreign Affairs for financing an additional 3 months fieldwork in the Sunnmore Islands. My sincere thanks also go to Prof Ragni Piene who employed me on a part time basis thereby allowing me to spend an additional year in Oslo when I was without funding. In Norway I would like to thank Dr P S Anderson who acted as my supervisor. Thanks are likewise due to Dr H Kongsrud of the Norwegian State Archives and to Dr T Scmidt of the Place Name Institute, both of whom were generous with their time. -

Walks and Scrambles in the Highlands

Frontispiece} [Photo by Miss Omtes, SLIGACHAN BRIDGE, SGURR NAN GILLEAN AND THE BHASTEIR GROUP. WALKS AND SCRAMBLES IN THE HIGHLANDS. BY ARTHUR L. BAGLEY. WITH TWELVE ILLUSTRATIONS. Xon&on SKEFFINGTON & SON 34 SOUTHAMPTON STREET, STRAND, W.C. PUBLISHERS TO HIS MAJESTY THE KING I9H Richard Clav & Sons, Limiteu, brunswick street, stamford street s.e., and bungay, suffolk UNiVERi. CONTENTS BEN CRUACHAN ..... II CAIRNGORM AND BEN MUICH DHUI 9 III BRAERIACH AND CAIRN TOUL 18 IV THE LARIG GHRU 26 V A HIGHLAND SUNSET .... 33 VI SLIOCH 39 VII BEN EAY 47 VIII LIATHACH ; AN ABORTIVE ATTEMPT 56 IX GLEN TULACHA 64 X SGURR NAN GILLEAN, BY THE PINNACLES 7i XI BRUACH NA FRITHE .... 79 XII THROUGH GLEN AFFRIC 83 XIII FROM GLEN SHIEL TO BROADFORD, BY KYLE RHEA 92 XIV BEINN NA CAILLEACH . 99 XV FROM BROADFORD TO SOAY . 106 v vi CONTENTS CHAF. PACE XVI GARSBHEINN AND SGURR NAN EAG, FROM SOAY II4 XVII THE BHASTEIR . .122 XVIII CLACH GLAS AND BLAVEN . 1 29 XIX FROM ELGOL TO GLEN BRITTLE OVER THE DUBHS 138 XX SGURR SGUMA1N, SGURR ALASDAIR, SGURR TEARLACH AND SGURR MHIC CHOINNICH . I47 XXI FROM THURSO TO DURNESS . -153 XXII FROM DURNESS TO INCHNADAMPH . 1 66 XXIII BEN MORE OF ASSYNT 1 74 XXIV SUILVEN 180 XXV SGURR DEARG AND SGURR NA BANACHDICH . 1 88 XXVI THE CIOCH 1 96 1 LIST OF ILLUSTRATIONS Toface page SLIGACHAN BRIDGE, SGURR NAN GILLEAN AND THE bhasteir group . Frontispiece BEN CRUACHAN, FROM NEAR DALMALLY . 4 LOCH AN EILEAN ....... 9 AMONG THE CAIRNGORMS ; THE LARIG GHRU IN THE DISTANCE . -31 VIEW OF SKYE, FROM NEAR KYLE OF LOCH ALSH . -

Bishops, Priests, Monks and Their Patrons the Lords of the Isles and the Church

CHAPTER 5 Bishops, Priests, Monks and Their Patrons The Lords of the Isles and the Church Sarah Thomas Whilst the MacDonald contribution to the Church, and in particular to Iona, has been discussed, their involvement in the patronage of parish churches and secular clergy has up until now been neglected.1 This is an area of immense potential, given the surviving source material in the papal archives; through the study of clerical identities, building on the work of John Bannerman, we are able to identify connections between the clergy and the Lords of the Isles.2 The Lordship of the Isles incorporated two bishoprics, four monastic houses and approximately 64 parish churches of which the Lords had patronage of 41.3 In an age where the appropriation of parish churches to monastic and ecclesias- tical authorities was widespread, the Lordship’s patronage of so many parish churches meant that they had considerable influence over clerical careers and had significant scope to reward kindreds. However, that amount of control over ecclesiastical benefices might strain relations between lord and bishop. Relations with the monastic institutions were not always smooth either; a par- ticular issue was the admission of MacKinnons into the monastery of Iona. The Lordship lands lay within two dioceses; their lands in the Hebrides in the diocese of Sodor and their lands in Kintyre, Knapdale, Lochaber, Moidart, 1 Steer and Bannerman, Late Medieval Monumental Sculpture; Bannerman, ‘Lordship of the Isles’; M. MacGregor, ‘Church and Culture in the late medieval Highlands’ in J. Kirk (ed), The Church in the Highlands (Edinburgh, 1998); R.D. -

Where to Go: Puffin Colonies in Ireland Over 15,000 Puffin Pairs Were Recorded in Ireland at the Time of the Last Census

Where to go: puffin colonies in Ireland Over 15,000 puffin pairs were recorded in Ireland at the time of the last census. We are interested in receiving your photos from ANY colony and the grid references for known puffin locations are given in the table. The largest and most accessible colonies here are Great Skellig and Great Saltee. Start Number Site Access for Pufferazzi Further information Grid of pairs Access possible for Puffarazzi, but Great Skellig V247607 4,000 worldheritageireland.ie/skellig-michael check local access arrangements Puffin Island - Kerry V336674 3,000 Access more difficult Boat trips available but landing not possible 1,522 Access possible for Puffarazzi, but Great Saltee X950970 salteeislands.info check local access arrangements Mayo Islands l550938 1,500 Access more difficult Illanmaster F930427 1,355 Access more difficult Access possible for Puffarazzi, but Cliffs of Moher, SPA R034913 1,075 check local access arrangements Stags of Broadhaven F840480 1,000 Access more difficult Tory Island and Bloody B878455 894 Access more difficult Foreland Kid Island F785435 370 Access more difficult Little Saltee - Wexford X968994 300 Access more difficult Inishvickillane V208917 170 Access more difficult Access possible for Puffarazzi, but Horn Head C005413 150 check local access arrangements Lambay Island O316514 87 Access more difficult Pig Island F880437 85 Access more difficult Inishturk Island L594748 80 Access more difficult Clare Island L652856 25 Access more difficult Beldog Harbour to Kid F785435 21 Access more difficult Island Mayo: North West F483156 7 Access more difficult Islands Ireland’s Eye O285414 4 Access more difficult Howth Head O299389 2 Access more difficult Wicklow Head T344925 1 Access more difficult Where to go: puffin colonies in Inner Hebrides Over 2,000 puffin pairs were recorded in the Inner Hebrides at the time of the last census. -

South Skye Web.Indd

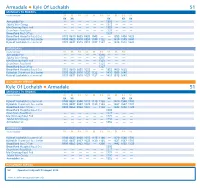

Armadale G Kyle Of Lochalsh 51 MONDAYS TO FRIDAYS route number 51 51 51 51 51 51 51 51 51 51 XX XX XX XX XX Armadale Pier — — — — — — 1310 — — — Sabhal Mor Ostaig — — — — — — 1315 — — — Isle Oronsay Road End — — — — — — 1323 — — — Drumfearn Road End — — — — — — 1328 — — — Broadford Post Offi ce — — — — — — 1337 — — — Broadford Hospital Road End 0715 0810 0855 0935 1045 — — 1355 1450 1625 Kyleakin Shorefront bus shelter 0730 0825 0910 0950 1100 1122 — 1410 1505 1640 Kyle of Lochalsh bus terminal 0737 0831 0915 0957 1107 1127 — 1415 1512 1647 SATURDAYS route number 51 51 51 51 51 51 51 51 51 Armadale Pier — — — — — 1310 — — — Sabhal Mor Ostaig — — — — — 1315 — — — Isle Oronsay Road End — — — — — 1323 — — — Drumfearn Road End — — — — — 1328 — — — Broadford Post Offi ce — — — — — 1337 — — — Broadford Hospital Road End 0715 0810 0855 1005 — — 1355 1450 1625 Kyleakin Shorefront bus shelter 0730 0825 0910 1020 1122 — 1410 1505 1640 Kyle of Lochalsh bus terminal 0737 0831 0915 1027 1127 — 1415 1512 1647 NO SUNDAY SERVICE Kyle Of Lochalsh G Armadale 51 MONDAYS TO FRIDAYS route number 51 51 51 51 51 51 51 51 51 51 XX XX XX XX XX Kyle of Lochalsh bus terminal 0740 0832 0900 1015 1115 1138 — 1420 1540 1700 Kyleakin Shorefront bus shelter 0745 0837 0907 1022 1120 1143 — 1427 1547 1707 Broadford Post Offi ce 0800 0852 0922 1037 — 1158 — 1442 1602 1722 Broadford Hospital Road End — — — — — — 1205 — — — Drumfearn Road End — — — — — — 1217 — — — Isle Oronsay Road End — — — — — — 1222 — — — Sabhal Mor Ostaig — — — — — — 1230 — — — Armadale Pier — — — — — — -

Kintour Landscape Survey Report

DUN FHINN KILDALTON, ISLAY AN ARCHAEOLOGICAL SURVEY DATA STRUCTURE REPORT May 2017 Roderick Regan Summary The survey of Dun Fhinn and its associated landscape has revealed a picture of an area extensively settled and utilised in the past dating from at least the Iron Age and very likely before. In the survey area we see settlements developing across the area from at least the 15 th century with a particular concentration of occupation on or near the terraces of the Kintour River. Without excavation or historical documentation dating these settlements is fraught with difficulty but the distinct differences between the structures at Ballore and Creagfinn likely reflect a chronological development between the pre-improvement and post-improvement settlements, the former perhaps a relatively rare well preserved survival. Ballore Kilmartin Museum Argyll, PA31 8RQ Tel: 01546 510 278 [email protected] Scottish Charity SC022744 ii Contents 1. Introduction 1 2. Archaeological and Historical Background 2 2.1 Cartographic Evidence of Settlement 4 2.2 Some Settlement History 6 2.3 A Brief History of Landholding on Islay 10 3. Dun Fhinn 12 4. Walkover Survey Results 23 5. Discussion 47 6. References 48 Appendix 1: Canmore Extracts 50 The Survey Team iii 1. Introduction This report collates the results of the survey of Dun Fhinn and a walkover survey of the surrounding landscape. The survey work was undertaken as part of the Ardtalla Landscape Project a collaborative project between Kilmartin Museum and Reading University, which forms part of the wider Islay Heritage Project. The survey area is situated on the Ardtalla Estate within Kildalton parish in the south east of Islay (Figure 1) and survey work was undertaken in early April 2017. -

Layout 1 Copy

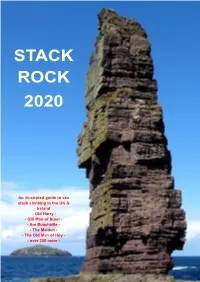

STACK ROCK 2020 An illustrated guide to sea stack climbing in the UK & Ireland - Old Harry - - Old Man of Stoer - - Am Buachaille - - The Maiden - - The Old Man of Hoy - - over 200 more - Edition I - version 1 - 13th March 1994. Web Edition - version 1 - December 1996. Web Edition - version 2 - January 1998. Edition 2 - version 3 - January 2002. Edition 3 - version 1 - May 2019. Edition 4 - version 1 - January 2020. Compiler Chris Mellor, 4 Barnfield Avenue, Shirley, Croydon, Surrey, CR0 8SE. Tel: 0208 662 1176 – E-mail: [email protected]. Send in amendments, corrections and queries by e-mail. ISBN - 1-899098-05-4 Acknowledgements Denis Crampton for enduring several discussions in which the concept of this book was developed. Also Duncan Hornby for information on Dorset’s Old Harry stacks and Mick Fowler for much help with some of his southern and northern stack attacks. Mike Vetterlein contributed indirectly as have Rick Cummins of Rock Addiction, Rab Anderson and Bruce Kerr. Andy Long from Lerwick, Shetland. has contributed directly with a lot of the hard information about Shetland. Thanks are also due to Margaret of the Alpine Club library for assistance in looking up old journals. In late 1996 Ben Linton, Ed Lynch-Bell and Ian Brodrick undertook the mammoth scanning and OCR exercise needed to transfer the paper text back into computer form after the original electronic version was lost in a disk crash. This was done in order to create a world-wide web version of the guide. Mike Caine of the Manx Fell and Rock Club then helped with route information from his Manx climbing web site. -

Discovering Bonnie Prince Charlie and the Jacobites

DISCOVERING BONNIE PRINCE CHARLIE & THE JACOBITES NATIONAL MUSEUM PALACE OF EDINBURGH STIRLING KILLIECRANKIE ALLOA TOWER LINLITHGOW OF SCOTLAND HOLYROODHOUSE CASTLE CASTLE PALACE DOUNE CASTLE The National Trust for Scotland HUNTINGTOWER Historic Scotland CASTLE National Museum of Scotland Palace of Holyroodhouse CULLODEN BATTLEFIELD Thurso BRODIE CASTLE Lewis FORT GEORGE Ullapool Harris Poolewe North Fraserburgh Uist Cromarty Brodie Castle URQUHART A98 Benbecula Fort George A98 CASTLE A947 Nairn A96 South Uist Fyvie Castle Skye Kyle of Inverness Culloden Huntly Lochalsh Battlefield Kildrummy A97 Leith Hall Barra Urquhart Castle Canna Castle DRUM CASTLE A887 A9 Castle Fraser A944 A87 Kingussie Corgarff Aberdeen Rum Glenfinnan Castle Craigievar Drum Monument A82 Castle A830 A86 Eigg Castle Fort William A93 A90 A92 A9 House Killiecrankie of Dun FYVIE CASTLE A861 Glencoe Pitlochry A924 Montrose Tobermory A933 A82 Glamis Dunkeld Craignure Dunstaffnage Castle A827 A822 Dundee Staffa Burg A92 Mull A85 Crianlarich Perth Huntingtower CASTLE FRASER Iona Oban A85 Castle A9 St Andrews M90 Doune Castle Alloa Tower Stirling Castle Stirling Helensburgh A811 Edinburgh Tenement M80 CRAIGIEVAR House Glasgow CASTLE Linlithgow A8 Dumbarton Edinburgh Palace A1 Glasgow Castle M8 A74 A7 Berwick M77 EdinburghA68 M74 Pollok House Ardrossan A737 A736 Castle M74 A72 A83 National Palace of LEITH HALL A726 Holmwood A749 A841 Museum of Holyroodhouse Ayr Scotland Greenbank Garden A725 A68 Moffat DUMBARTON DUNSTAFFNAGE GLENFINNAN GLENCOE HOUSE OF DUN CORGARFF KILDRUMMY CASTLE CASTLE MONUMENT Dumfries CASTLE CASTLE Stranraer Kirkcudbright The Palace of Holyroodhouse image: Royal Collection Trust/© Her Majesty Queen Elizabeth II 2016. Photographer: Sandy Young DISCOVERING BONNIE PRINCE CHARLIE & THE JACOBITES The story of Prince Charles Edward Stuart (Bonnie Prince Charlie) and the Jacobites is embedded in Scotland’s rich and turbulent history, resonating across the centuries. -

Mid Ebudes Vice County 103 Rare Plant Register Version 1 2013

Mid Ebudes Vice County 103 Rare Plant Register Version 1 2013 Lynne Farrell Jane Squirrell Graham French Mid Ebudes Vice County 103 Rare Plant Register Version 1 Lynne Farrell, Jane Squirrell and Graham French © Lynne Farrell, BSBI VCR. 2013 Contents 1. INTRODUCTION ................................................................................................................................... 1 2. VC 103 MAP ......................................................................................................................................... 4 3. EXTANT TAXA ...................................................................................................................................... 5 4. PLATES............................................................................................................................................... 10 5. RARE PLANT REGISTER ....................................................................................................................... 14 6. EXTINCT SPECIES .............................................................................................................................. 119 7. RECORDERS’ NAME AND INITIALS .................................................................................................... 120 8. REFERENCES .................................................................................................................................... 123 Cover image: Cephalanthera longifolia (Narrow-leaved Helleborine) [Photo Lynne Farrell] Mid Ebudes Rare Plant Register -

The Seventh Argyll Bird Report

THE SEVENTH ARGYLL BIRD REPORT PUBLISHED BY THE ARGYLL BIRD CLUB 1991 Argyll Bird Club The Argyll Bird Club was formed in 1985 and aims to play an active role in the promotion of ornitholo and conservation within Argyll, in the District of Argyll and Bute, in Stra%clyde Region. The club has steadily built up its membership to the present level of around 170. One da Jon meeting is held in the spring and another in the autumn, these inch8% e tal s, scientific papersand field trips. Conferences on selected topics are also organised occasionally. In 1986 the club held its first conference, a successful meeting between foresters and biid conser- vationists. This was followed in 1987 with a two-day conference in Oban on fish farming and the environment. The club has close contacts with other conseKvation groups both locally and nationally, Zncluding the British Trustfor Orqitholofy, the Royal Societ for the Protection of Birds. Scottish Ornithologists’- C ub and the Scottisl Naturalists’ Trust. Membership of the club promote sagreater interest in birds throu h indi. vidual and shared participation in various recording and surveying sca emes, and the dissemination of this information to members thro-ugh four newslet- terseachyear and theannual Argyll BirdReporf.Thereport isdistributed free to all members (one per family membership) and is the major publication of the club. Most of the annual subscription is used to pay for this. Corporate membership of the Club is also available to hotels, companies and other write to the Back copies of earlier reports THE SEVENTH ARGYLL BIRD REPORT Edited by: S. -

The General Lighthouse Fund 2003-2004 HC

CONTENTS Foreword to the accounts 1 Performance Indicators for the General Lighthouse Authorities 7 Constitutions of the General Lighthouse Authorities and their board members 10 Statement of the responsibilities of the General Lighthouse Authorities’ boards, Secretary of State for Transport and the Accounting Officer 13 Statement of Internal control 14 Certificate of the Comptroller and Auditor General to the Houses of Parliament 16 Income and expenditure account 18 Balance sheet 19 Cash flow statement 20 Notes to the accounts 22 Five year summary 40 Appendix 1 41 Appendix 2 44 iii FOREWORD TO THE ACCOUNTS for the year ended 31 March 2004 The report and accounts of the General Lighthouse Fund (the Fund) are prepared pursuant to Section 211(5) of the Merchant Shipping Act 1995. Accounting for the Fund The Companies Act 1985 does not apply to all public bodies but the principles that underlie the Act’s accounting and disclosure requirements are of general application: their purpose is to give a true and fair view of the state of affairs of the body concerned. The Government therefore has decided that the accounts of public bodies should be prepared in a way that conforms as closely as possible with the Act’s requirements and also complies with Accounting Standards where applicable. The accounts are prepared in accordance with accounts directions issued by the Secretary of State for Transport. The Fund’s accounts consolidate the General Lighthouse Authorities’ (GLAs) accounts and comply as appropriate with this policy. The notes to the Bishop Rock Lighthouse accounts contain further information. Section 211(5) of the Merchant Shipping Act 1995 requires the Secretary of State to lay the Fund’s accounts before Parliament. -

Leabhar Nan Gleann = the Book of the Glens

i- H.fAJi. lu^yv^. tzZ/rc^ LEABHAR NAN GLEANN: THE BOOK OF THE . GLENS . ZIMMER ON PICTISH MATRIARCHY BY GEORGE HENDERSON, Ph.D. EDINBURGH : NORMAS MACLEOD, The Mound. INVERNESS : Woeks. 'Tub Highland News" Printing ihfiRARY ACCESSION PREFATORY NOTE. rnSE following pages are reprinted from ^l^ "The Highland Home Journal," the -L weekly supplement of "The Highland News," where they appeared for the first time. The sweet voices associated in my memory with so many of them, I know, I shall hear no more, and yet they abide with me in spirit. If for a little time they may enable any one else to share in a portion of the joy given me, my aim will have been amply fulfilled. My original intention was to restrict myself entirely—as I have to a good extent done—to unpublished sources, and to have included some Gaelic romances. When I had proceeded but a part of the way I had mapped out, inner considerations led me to offer some transliterations from the Fernàig MS., actuated in part also by a suggestion given by the editors in their preface. To give the whole, space fails me; but what is here given includes an interesting portion, and, perhaps, what is in all respects of most permanent significance. It was not my aim to obliterate dialectal traits unnecessarily. The shroud of the traditional orthography would here have often marred the living form; but I liave no quarrel with the rigid traditional scrjpt in its place. May I ven- ture to hope therefore that, as it is, my reading of Macrae's often puzzling, incon- Bistent phonetic spelling, does no great in- justice to a noble voice, which is to me daily deepening a long-cherished fondness for Kintail.