The Greater Production Campaign on The

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Saskatchewan Bound: Migration to a New Canadian Frontier

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln Great Plains Quarterly Great Plains Studies, Center for 1992 Saskatchewan Bound: Migration to a New Canadian Frontier Randy William Widds University of Regina Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/greatplainsquarterly Part of the Other International and Area Studies Commons Widds, Randy William, "Saskatchewan Bound: Migration to a New Canadian Frontier" (1992). Great Plains Quarterly. 649. https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/greatplainsquarterly/649 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Great Plains Studies, Center for at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in Great Plains Quarterly by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. SASKATCHEWAN BOUND MIGRATION TO A NEW CANADIAN FRONTIER RANDY WILLIAM WIDDIS Almost forty years ago, Roland Berthoff used Europeans resident in the United States. Yet the published census to construct a map of En despite these numbers, there has been little de glish Canadian settlement in the United States tailed examination of this and other intracon for the year 1900 (Map 1).1 Migration among tinental movements, as scholars have been this group was generally short distance in na frustrated by their inability to operate beyond ture, yet a closer examination of Berthoff's map the narrowly defined geographical and temporal reveals that considerable numbers of migrants boundaries determined by sources -

A THREAT to LEADERSHIP: C.A.Dunning and Mackenzie King

S. Peter Regenstreif A THREAT TO LEADERSHIP: C.A.Dunning and Mackenzie King BY Now mE STORY of the Progressive revolt and its impact on the Canadian national party system during the 1920's is well documented and known. Various studies, from the pioneering effort of W. L. Morton1 over a decade ago to the second volume of the Mackenzie King official biography2 which has recently appeared, have dealt intensively with the social and economic bases of the movement, the attitudes of its leaders to the institutions and practices of national politics, and the behaviour of its representatives once they arrived in Ottawa. Particularly in biographical analyses, 3 a great deal of attention has also been given to the response of the established leaders and parties to this disrupting influence. It is clearly accepted that the roots of the subsequent multi-party situation in Canada can be traced directly to a specific strain of thought and action underlying the Progressivism of that era. At another level, however, the abatement of the Pro~ gressive tide and the manner of its dispersal by the end of the twenties form the basis for an important piece of Canadian political lore: it is the conventional wisdom that, in his masterful handling of the Progressives, Mackenzie King knew exactly where he was going and that, at all times, matters were under his complete control, much as if the other actors in the play were mere marionettes with King the manipu lator. His official biographers have demonstrated just how illusory this conception is and there is little to be added to their efforts on this score. -

Terms of Office

Terms of Office The Right Honourable Sir John Alexander Macdonald, 1 July 1867 - 5 November 1873, 17 October 1878 - 6 June 1891 The Right Honourable The Honourable Sir John A. Macdonald Alexander Mackenzie (1815-1891) (1822-1892) The Honourable Alexander Mackenzie, 7 November 1873 - 8 October 1878 The Honourable Sir John Joseph Caldwell Abbott, 16 June 1891 - 24 November 1892 The Right Honourable The Honourable The Right Honourable Sir John Joseph Sir John Sparrow Sir John Sparrow David Thompson, Caldwell Abbott David Thompson 5 December 1892 - 12 December 1894 (1821-1893) (1845-1894) The Honourable Sir Mackenzie Bowell, 21 December 1894 - 27 April 1896 The Right Honourable Sir Charles Tupper, 1 May 1896 - 8 July 1896 The Honourable The Right Honourable Sir Mackenzie Bowell Sir Charles Tupper The Right Honourable (1823-1917) (1821-1915) Sir Wilfrid Laurier, 11 July 1896 - 6 October 1911 The Right Honourable Sir Robert Laird Borden, 10 October 1911 - 10 July 1920 The Right Honourable The Right Honourable The Right Honourable Arthur Meighen, Sir Wilfrid Laurier Sir Robert Laird Borden (1841-1919) (1854-1937) 10 July 1920 - 29 December 1921, 29 June 1926 - 25 September 1926 The Right Honourable William Lyon Mackenzie King, 29 December 1921 - 28 June 1926, 25 September 1926 - 7 August 1930, 23 October 1935 - 15 November 1948 The Right Honourable The Right Honourable The Right Honourable Arthur Meighen William Lyon Richard Bedford Bennett, (1874-1960) Mackenzie King (later Viscount), (1874-1950) 7 August 1930 - 23 October 1935 The Right Honourable Louis Stephen St. Laurent, 15 November 1948 - 21 June 1957 The Right Honourable John George Diefenbaker, The Right Honourable The Right Honourable 21 June 1957 - 22 April 1963 Richard Bedford Bennett Louis Stephen St. -

GOVERNMENT Rt. Hon. Arthur Meighen, June 29, 1926

GOVERNMENT 607 Rt. Hon. Arthur Meighen, June 29, 1926 — With the enactment of the Ministries and September 25, 1926 Ministers of State Act (Government Organization Rt. Hon. William Lyon Mackenzie King, September 25, Act, 1970), five categories of ministers ofthe Crown 1926 — August 6, 1930 may be identified: departmental ministers, ministers with special parliamentary responsibilities, ministers Rt. Hon. Richard Bedford Bennett, August 7, 1930 — without portfolio, and three types of ministers of October 23, 1935 state. Ministers of state for designated purposes may Rt. Hon. William Lyon Mackenzie King, October 23, head a ministry of state created by proclamafion. 1935 — November 15, 1948 They are charged with developing new and compre Rt. Hon. Louis Stephen St-Laurent, November 15, hensive policies in areas of particular urgency and 1948 -June 21, 1957 importance and have a mandate determined by the Rt. Hon. John George Dicfenbaker, June 21, 1957 — Governor-in-Council. They may have powers, duties April 22, 1963 and functions and exercise supervision and control of elements of the public service, and may seek Rt. Hon. Lester Bowles Pearson, April 22, 1963 — April 20, 1968 parliamentary appropriations to cover the cost of their staff and operations. Other ministers of state Rt. Hon. Pierre EllioU Trudeau, April 20, 1968 — may be appointed to assist departmental ministers June 4, 1979 with their responsibilities. They may have powers, Rt. Hon. Joe Clark, June 4, 1979 — March 3, 1980 duties and functions delegated to them by the Rt. Hon. Pierre EllioU Trudeau, March 3, 1980 — departmental minister, who retains ultimate legal June 30, 1984 responsibility. -

The Encyclopedia of Saskatchewan | Details File:///T:/Uofrpress/Encyclopedia of SK - Archived/Esask-Uregina-Ca/Entr

The Encyclopedia of Saskatchewan | Details file:///T:/uofrpress/Encyclopedia of SK - Archived/esask-uregina-ca/entr... BROWSE BY SUBJECT ENTRY LIST (A-Z) IMAGE INDEX CONTRIBUTOR INDEX ABOUT THE ENCYCLOPEDIA SEARCH DEWDNEY, EDGAR (1835–1916) Welcome to the Encyclopedia of Saskatchewan. For assistance in Edgar Dewdney was born in Bideford, Devonshire, England exploring this site, please click here. on November 5, 1835, to a prosperous family. Arriving in Victoria in the Crown Colony of Vancouver Island in May 1859 during a GOLD rush, he spent more than a decade surveying and building trails through the mountains on the If you have feedback regarding this mainland. In 1872, shortly after British Columbia’s entry entry please fill out our feedback into Confederation, he was elected MP for Yale and form. became a loyal devotee of John A. Macdonald and the Conservative Party. In Parliament he pursued the narrow agenda of getting the transcontinental railway built with the terminal route via the Fraser Valley, where he happened to have real estate interests. In 1879 Dewdney became Indian commissioner of the Edgar Dewdney. North-West Territories (NWT) with the immediate task of Saskatchewan Archives averting mass starvation and unrest among the First Board R-B48-1 Nations following the sudden disappearance of the buffalo. Backed by a small contingent of Indian agents and Mounted Police, he used the distribution of rations as a device to impose state authority on the First Nations population. Facing hunger and destitution, First Nations people were compelled to settle on reserves, adopt agriculture and send their children to mission schools. -

University of Alberta Perceptions and Parameters of Education As A

University of Alberta Perceptions and Parameters of Education as a Treaty Right within the Context of Treaty 7 Sheila Carr-Stewart A thesis submitted to the Faculîy of Graduate Studies and Research in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Educational Administration and Leadership Department of Educational Policy Studies Edmonton, Alberta spring 2001 National Library Bibliothèque nationale m*u ofCanada du Canada Acquisitions and Acquisitions et Bibliographk Services services bibliographiques 395 Wellington Street 395. nie Wellington Ottawa ON KIA ON4 Oîîawa ON K1A ON4 Canada Canada The author has granted a non- L'auteur a accordé une licence non exclusive licence allowing the exclusive permettant à la National Library of Canada to Bibliothèque nationale du Canada de reproduce, loan, distribute or sell reproduire, prêter, distribuer ou copies of this thesis in microform, vendre des copies de cette thèse sous paper or electronic formats. la forme de microfiche/nlm, de reproduction sur papier ou sur format électronique. The author retains ownership of the L'auteur conserve la propriété du copyright in this thesis. Neither the droit d'auteur qui protège cette thèse. thesis nor substantid extracts fkom it Ni la thèse ni des extraits substantiels may be printed or othenirise de celle-ci ne doivent êeimprimés reproduced without the author's ou autrement reproduits sans son permission. autorisation . In memory of John and Betty Carr and Pat and MyrtIe Stewart Abstract On September 22, 1877, representatives of the Blackfoot Confederacy, Tsuu T'ha and Stoney Nations, and Her Majesty's Govemment signed Treaty 7. Over the next century, Canada provided educational services based on the Constitution Act, Section 91(24). -

The Canadian Bar Review

THE CANADIAN BAR REVIEW THE CANADIAN BAR REVIEW is the organ of the Canadian Bar Association, and it is felt that its pages should be open to free and fair discussion of all matters of interest to the legal profession in Canada. The Editor, however, wishes it to be understood that opinions expressed in signed articles are those of the individual writers only, and that the REVIEW does not assume any responsibility for them. It is hoped that members of the profession will favour the Editor from time to time with notes of important cases determined by the Courts in which they practise. Contributors' manuscripts must be typed before being sent to the Editor at the Exchequer Court Building, Ottawa . TOPICS OF THE MONTH. ACADEMIC HONOURS FOR THE PRESIDENT OF THE C.B .A. -Our readers will be interested to learn that at a Convocation of Queen's University, held on the 12th of last month, Sir James Aikins, K.C ., President of the Canadian Bar Association, received the honorary degree of Doctor of Laws . Sir Robert Borden, K.C ., Chancellor of the University, presided at the Convocation . At the same time simi- lar degrees were conferred upon His Excellency the Governor- General of the Dominion and Sir Clifford Sifton . Four other insti- tutions of learning in Canada had preceded Queen's University in paying a tribute to the distinguished place held by Sir James Aikins as a citizen of Canada, namely, the University of Manitoba in 1919, Alberta University and McMaster University in 1921, and Toronto University in 1924 . -

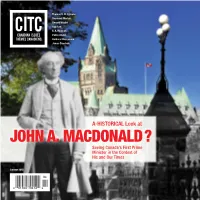

JOHN A. MACDONALD ? Seeing Canada's First Prime Minister in the Context of His and Our Times

Thomas H. B. Symons Desmond Morton Donald Wright Bob Rae E. A. Heaman Patrice Dutil Barbara Messamore James Daschuk A-HISTORICAL Look at JOHN A. MACDONALD ? Seeing Canada's First Prime Minister in the Context of His and Our Times Summer 2015 Introduction 3 Macdonald’s Makeover SUMMER 2015 Randy Boswell John A. Macdonald: Macdonald's push for prosperity 6 A Founder and Builder 22 overcame conflicts of identity Thomas H. B. Symons E. A. Heaman John Alexander Macdonald: Macdonald’s Enduring Success 11 A Man Shaped by His Age 26 in Quebec Desmond Morton Patrice Dutil A biographer’s flawed portrait Formidable, flawed man 14 reveals hard truths about history 32 ‘impossible to idealize’ Donald Wright Barbara Messamore A time for reflection, Acknowledging patriarch’s failures 19 truth and reconciliation 39 will help Canada mature as a nation Bob Rae James Daschuk Canadian Issues is published by/Thèmes canadiens est publié par Canada History Fund Fonds pour l’histoire du Canada PRÉSIDENT/PResIDENT Canadian Issues/Thèmes canadiens is a quarterly publication of the Association for Canadian Jocelyn Letourneau, Université Laval Studies (ACS). It is distributed free of charge to individual and institutional members of the ACS. INTRODUCTION PRÉSIDENT D'HONNEUR/HONORARY ChaIR Canadian Issues is a bilingual publication. All material prepared by the ACS is published in both The Hon. Herbert Marx French and English. All other articles are published in the language in which they are written. SecRÉTAIRE DE LANGUE FRANÇAISE ET TRÉSORIER/ MACDONALd’S MAKEOVER FRENch-LaNGUAGE SecRETARY AND TReasURER Opinions expressed in articles are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the opinion of Vivek Venkatesh, Concordia University the ACS. -

Richard Bedford Bennett

Richard Bedford Bennett Biography I propose that any government of which I am the head will at the first Richard Bedford Bennett was born in Hopewell Hill, New Brunswick subsistence living. Relief for unemployed families was administered on a th session of Parliament initiate whatever action is necessary to that end, or in 1870, the son of a shipbuilder. After finishing Grade 8, he went municipal level. Attempts by Bennett to coordinate welfare on a federal Canada’s prime minister perish in the attempt.—R. B. Bennett, June 9, 1930, on the elimination to Normal School and trained as a teacher. By the age of 16 he was and provincial level were rejected by the provinces. of unemployment teaching near Moncton and two years later, became school principal in Douglastown. At the same time, he began articling part-time in a By 1933, the Depression was at its worst and Bennett’s government 11 law office. By 1890, Bennett had saved enough money to study law appeared indecisive and ineffectual. He became the butt of jokes such at Dalhousie University. He graduated in 1893, and joined a local law as “Bennett buggies,” cars pulled by horses or oxen because the owners firm. In 1897, he moved to Calgary and became the law partner of could no longer afford gasoline. Dissension was widespread throughout Conservative Senator James A. Lougheed. the party and Cabinet due to Bennett’s inability to delegate authority. He held the portfolios for finance and for external affairs, and his failure His first foray into politics had been as alderman in Chatham, New to consult with Cabinet angered his ministers. -

The Men in Sheepskin Coats Tells the Story of the Beginning of Stories About Western Canada in These Countries

THE MEN IN SHEEP S KIN COA ts Online Resource By Myra Junyk © 2010 Curriculum Plus By Myra Junyk Editor: Sylvia Gunnery We acknowledge the financial support of The Government of Canada through the Book Publishing Industry Development Program (BPIDP) for our publishing activities. Curriculum Plus Publishing Company 100 Armstrong Avenue Georgetown, ON L7G 5S4 Toll free telephone 1-888-566-9730 Toll free fax 1-866-372-7371 E-mail [email protected] www.curriculumplus.ca Background A Summary of the Script Eastern Europe. Writers and speakers were paid to spread exciting The Men in Sheepskin Coats tells the story of the beginning of stories about Western Canada in these countries. Foreign journalists Ukrainian immigration to the Canadian West. Wasyl Eleniak and were brought to Canada so that they could promote the country Ivan Pylypiw, the first “men in sheepskin coats,” came to Canada when they returned home. from the province of Galicia in Ukraine on September 7, 1891. Prime Minister Wilfrid Laurier and Minister of the Interior Clifford One of the main groups that responded to the advertising campaign Sifton wanted to build a strong Canada by promoting immigration. was the Ukrainians. In 1895, the Ukranians did not have a country Doctor Joseph Oleskiw encouraged Ukrainian farmers such as Ivan of their own. Some of them lived in the provinces of the Austro- Nimchuk and his family to come to Canada. Many other Ukrainians Hungarian Empire while others lived under the Tsar of Russia. Their followed them. rulers spoke other languages and had customs that seemed strange. The small farmers of the province of Galicia in Western Ukraine felt Settlement of the Canadian West crushed by the Polish overlords. -

Imperial Plots Roundtable Commentary: a Reply Sarah Carter

Document generated on 09/27/2021 10:22 a.m. Journal of the Canadian Historical Association Revue de la Société historique du Canada Imperial Plots Roundtable Commentary: A Reply Sarah Carter Volume 29, Number 1, 2018 URI: https://id.erudit.org/iderudit/1065724ar DOI: https://doi.org/10.7202/1065724ar See table of contents Publisher(s) The Canadian Historical Association / La Société historique du Canada ISSN 0847-4478 (print) 1712-6274 (digital) Explore this journal Cite this document Carter, S. (2018). Imperial Plots Roundtable Commentary: A Reply. Journal of the Canadian Historical Association / Revue de la Société historique du Canada, 29(1), 190–204. https://doi.org/10.7202/1065724ar All Rights Reserved © The Canadian Historical Association / La Société This document is protected by copyright law. Use of the services of Érudit historique du Canada, 2018 (including reproduction) is subject to its terms and conditions, which can be viewed online. https://apropos.erudit.org/en/users/policy-on-use/ This article is disseminated and preserved by Érudit. Érudit is a non-profit inter-university consortium of the Université de Montréal, Université Laval, and the Université du Québec à Montréal. Its mission is to promote and disseminate research. https://www.erudit.org/en/ JOURNAL OF THE CHA 2018 | REVUE DE LA SHC Imperial Plots Roundtable Commentary: A Reply SARAH CARTER I am honoured and grateful to have such a distinguished group of col- leagues discuss Imperial Plots. Thanks to Jarvis Brownlie for organizing the panel and to Lara Campbell, Valerie Korinek, Carolyn Podruchny, and Katherine McKenna for their thoughtful and astute comments and insights at the University of Regina meeting of the CHA. -

The Canadian Parliamentary Guide

NUNC COGNOSCO EX PARTE THOMAS J. BATA LI BRARY TRENT UNIVERSITY us*<•-« m*.•• ■Jt ,.v<4■■ L V ?' V t - ji: '^gj r ", •W* ~ %- A V- v v; _ •S I- - j*. v \jrfK'V' V ■' * ' ’ ' • ’ ,;i- % »v • > ». --■ : * *S~ ' iJM ' ' ~ : .*H V V* ,-l *» %■? BE ! Ji®». ' »- ■ •:?■, M •* ^ a* r • * «'•# ^ fc -: fs , I v ., V', ■ s> f ** - l' %% .- . **» f-•" . ^ t « , -v ' *$W ...*>v■; « '.3* , c - ■ : \, , ?>?>*)■#! ^ - ••• . ". y(.J, ■- : V.r 4i .» ^ -A*.5- m “ * a vv> w* W,3^. | -**■ , • * * v v'*- ■ ■ !\ . •* 4fr > ,S<P As 5 - _A 4M ,' € - ! „■:' V, ' ' ?**■- i.." ft 1 • X- \ A M .-V O' A ■v ; ■ P \k trf* > i iwr ^.. i - "M - . v •?*»-• -£-. , v 4’ >j- . *•. , V j,r i 'V - • v *? ■ •.,, ;<0 / ^ . ■'■ ■ ,;• v ,< */ ■" /1 ■* * *-+ ijf . ^--v- % 'v-a <&, A * , % -*£, - ^-S*.' J >* •> *' m' . -S' ?v * ... ‘ *•*. * V .■1 *-.«,»'• ■ 1**4. * r- * r J-' ; • * “ »- *' ;> • * arr ■ v * v- > A '* f ' & w, HSi.-V‘ - .'">4-., '4 -' */ ' -',4 - %;. '* JS- •-*. - -4, r ; •'ii - ■.> ¥?<* K V' V ;' v ••: # * r * \'. V-*, >. • s s •*•’ . “ i"*■% * % «. V-- v '*7. : '""•' V v *rs -*• * * 3«f ' <1k% ’fc. s' ^ * ' .W? ,>• ■ V- £ •- .' . $r. « • ,/ ••<*' . ; > -., r;- •■ •',S B. ' F *. ^ , »» v> ' ' •' ' a *' >, f'- \ r ■* * is #* ■ .. n 'K ^ XV 3TVX’ ■■i ■% t'' ■ T-. / .a- ■ '£■ a« .v * tB• f ; a' a :-w;' 1 M! : J • V ^ ’ •' ■ S ii 4 » 4^4•M v vnU :^3£'" ^ v .’'A It/-''-- V. - ;ii. : . - 4 '. ■ ti *%?'% fc ' i * ■ , fc ' THE CANADIAN PARLIAMENTARY GUIDE AND WORK OF GENERAL REFERENCE I9OI FOR CANADA, THE PROVINCES, AND NORTHWEST TERRITORIES (Published with the Patronage of The Parliament of Canada) Containing Election Returns, Eists and Sketches of Members, Cabinets of the U.K., U.S., and Canada, Governments and Eegisla- TURES OF ALL THE PROVINCES, Census Returns, Etc.