Introduction

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Flower of English Chivalry

David Green. Edward the Black Prince: Power in Medieval Europe. Harlow: Pearson Longman, 2007. 312 pp. $28.00, paper, ISBN 978-0-582-78481-9. Reviewed by Stephen M. Cooper Published on H-War (January, 2008) In the city square of Leeds in West Yorkshire, the 1360s. He never became king of England, but there is a magnificent statue of the Black Prince, he was the sovereign ruler of a large part of erected in 1903 when the British Empire was at its France. The prince was a brilliant soldier and height and patriotism was uncomplicated. Dis‐ commander, but he was "not a political animal," playing an intense pride in his life and achieve‐ and there is a strong argument for saying that he ments, the inscription proclaims that the prince won the war but lost the peace because of his mis‐ was "the victor of Crécy and Poitiers, the Flower government of Aquitaine (p. 153). In pursuing his of English Chivalry and the Upholder of the Rights chosen themes, Green deliberately plays down the of the People in the Good Parliament." One would fighting, at which the prince was very good, and not expect a book published in 2007 to make the concentrates on the politics, where the prince was same grandiose claims, and David Green does not either rather hopeless or simply uninterested. In even intend his newest book Edward the Black terms of religion and estate management, there is Prince to be a conventional biography--he has no real evidence that "the Flower of English written one of those already (The Black Prince Chivalry" was even personally involved. -

Shakespeare's

Shakespeare’s Henry IV: s m a r t The Shadow of Succession SHARING MASTERWORKS OF ART April 2007 These study materials are produced for use with the AN EDUCATIONAL OUTREACH OF BOB JONES UNIVERSITY Classic Players production of Henry IV: The Shadow of Succession. The historical period The Shadow of Succession takes into account is 1402 to 1413. The plot focuses on the Prince of Wales’ preparation An Introduction to to assume the solemn responsibilities of kingship even while Henry IV regards his unruly son’s prospects for succession as disastrous. The Shadow of When the action of the play begins, the prince, also known as Hal, finds himself straddling two worlds: the cold, aristocratic world of his Succession father’s court, which he prefers to avoid, and the disreputable world of Falstaff, which offers him amusement and camaraderie. Like the plays from which it was adapted, The Shadow of Succession offers audiences a rich theatrical experience based on Shakespeare’s While Henry IV regards Falstaff with his circle of common laborers broad vision of characters, events and language. The play incorporates a and petty criminals as worthless, Hal observes as much human failure masterful blend of history and comedy, of heroism and horseplay, of the in the palace, where politics reign supreme, as in the Boar’s Head serious and the farcical. Tavern. Introduction, from page 1 Like Hotspur, Falstaff lacks the self-control necessary to be a produc- tive member of society. After surviving at Shrewsbury, he continues to Grieved over his son’s absence from court at a time of political turmoil, squander his time in childish pleasures. -

The Wars of the Roses: a Timeline of Key Events Edward III Reigns From

The Wars of the Roses: A Timeline of Key Events . Edward III reigns from 1327 – 1377. Edward has many sons the heirs of which become the key players in the Wars of the Roses (see family tree). o Edward’s first son Edward (The Black Prince) dies in 1376. His son, Richard becomes Richard II following Edward III’s death and reigns from 1377 until 1399. o Edward’s third son Lionel also predeceases him. Lionel’s daughter, however, is integral to the claim made by The House of York to the throne at the time of the Wars of the Roses. Her granddaughter marries Richard, Duke of York who is the son of Edward III’s fifth son, Edmund, Duke of York. Their child Richard, 3rd Duke of York will eventually make a claim for the throne during the Wars of the Roses. o Edward’s fourth son John of Gaunt, Duke of Lancaster, founds The House of Lancaster. His son, Henry (Bolingbroke), overthrows Richard II to become Henry IV. The descendants of Henry IV are King Henry V and King Henry VI. The House of Lancaster therefore has an uninterrupted reign of 62 years. o Edward’s fifth son Edmund of Langley, Duke of York founds The House of York. His son Richard, 2nd Duke of York marries the great- granddaughter of Edward’s third son. 1377: Edward III dies, and Richard II, his grandson, becomes king. Richard II is overthrown by his cousin Henry Bolingbroke who becomes King Henry IV. 1413: Henry IV dies, and Henry V becomes king. -

History of the Plantagenet Kings of England [email protected]

History of the Plantagenet Kings of England [email protected] http://newsummer.com/presentations/Plantagenet Introduction Plantagenet: Pronunciation & Usage Salic Law: "of Salic land no portion of the inheritance shall come to a woman: but the whole inheritance of the land shall come to the male sex." Primogeniture: inheritance moves from eldest son to youngest, with variations Shakespeare's Plantagenet plays The Life and Death of King John Edward III (probably wrote part of it) Richard II Henry IV, Part 1 Henry IV, Part 2 Henry V Henry VI, Part 1 Henry VI, Part 2 Henry VI, Part 3 Richard III Brief assessments The greatest among them: Henry II, Edward I, Edward III The unfulfilled: Richard I, Henry V The worst: John, Edward II, Richard II, Richard III The tragic: Henry VI The Queens Matilda of Scotland, c10801118 (Henry I) Empress Matilda, 11021167 (Geoffrey Plantagent) Eleanor of Aquitaine, c11221204 (Henry II) Isabella of France, c12951348 (Edward II) Margaret of Anjou, 14301482 (Henry VI) Other key notables Richard de Clare "Strongbow," 11301176 William the Marshal, 1st Earl of Pembroke, 11471219 Simon de Montfort, 6th Earl of Leicester, c12081265 Roger Mortimer, Earl of March, 12871330 Henry "Hotspur" Percy, 13641403 Richard Neville "The Kingmaker," 14281471 Some of the important Battles Hastings (Wm I, 1066): Conquest Lincoln (Stephen, 1141): King Stephen captured Arsuf (Richard I, 1191): Richard defeats Salidin Bouvines (John, 1214): Normandy lost to the French Lincoln, 2nd (Henry III, 1217): Pembroke defeats -

Hundred Years

THE HUNDRED YEARS WAR HISTORY The Hundred Years War was fought between England and France from 1337 to 1453. The war was a series of battles with long periods of peace in between. In 1337, King Edward III of England claimed he was the rightful king of France. This started the long war between the two countries. FIGHTING Disputes caused fighting to continue for over one hundred years. These arguments were over the control of the valuable wool trade, disputes over areas of land, and the support for Scotland by the French. King Edward III believed he was the rightful heir to the French crown through his mother, Isabella. He claimed the right to the throne when he was fifteen because King Charles IV of France died without a male heir. The French chose Philip to be their king instead. When Philip VI of France took control of Aquitaine from the English in 1337, King Edward III decided to fight back. He invaded France and claimed his right to the French throne. EDWARD’S ARMY Edward did not attempt to conquer and control the French land, but instead raided the land in something called chevauchees. He struck deep into the land burning crops, plundering cities, and creating havoc. King Edward III’s army was led by his son, the valiant Edward the “Black Prince” during the 1350s. He was a famous hero to the English known for his chivalry. He led English troops to major victories over the French. During the battle of Poitiers, the Black Prince captured the current King of France, John II. -

Isabella of France: the Rebel Queen Free Download

ISABELLA OF FRANCE: THE REBEL QUEEN FREE DOWNLOAD Kathryn Warner | 336 pages | 15 Mar 2016 | Amberley Publishing | 9781445647401 | English | Chalford, United Kingdom Isabella of France Edward, highly dependent on Despenser, refused. Despite Isabella giving birth to her second son, JohninEdward's position was precarious. Subscribe Isabella of France: The Rebel Queen our weekly newsletter and join our 3, subscribers to stay up to date on History of Royal Women's articles! The 10 best English queens in history. Warner does a fantastic job to cut through all the myths and bullshit that have built up around the queen for centuries Isabella of France: The Rebel Queen even by historians themselves. I grew up in the north of England, and hold two degrees in medieval history and literature from the University of Manchester. Trivia About Isabella of Franc Isabella of France: The Rebel Queen somewhat familiar with this period, I noticed that Ms. Isabella was held under house arrest for a while, and was forced to give up the vast lands and income she had appropriated; she had awarded herself 20, marks or 13, pounds a year, the largest income anyone Isabella of France: The Rebel Queen England received the kings excepted in the entire Middle Ages. More on: United Kingdom. Henry of Lancaster was amongst the first to break with Isabella and Mortimer. If you've read my Edward book, you'll know that I demolish many myths which have been invented about him over the centuries and which many people assume are factual, and I do the same with Isabella. -

ABSTRACT the Military and Administrative Leadership of The

ABSTRACT The Military and Administrative Leadership of the Black Prince Ashley K. Tidwell, M.A. Mentor: Jeffrey S. Hamilton, Ph.D. Edward of Woodstock, Prince of Wales and Aquitaine (1330-1376), has been analyzed on many different levels for his military genius in battle during the Hundred Years War. Known as the Black Prince, Edward had an effective ruthlessness in battle that has made his military career and his chivalrous nature a subject of interest to historians. However, Edward was more than a military leader; he was a ruler. Becoming Prince of Aquitaine in 1362 after the Peace of Brétigny, Edward had to face a new role many have overlooked in his rather short lifetime: governor and leader of a foreign people. This role tends to be overlooked among the historical community, due in large part to the lack of primary documents. Regardless, this role was an important aspect of the prince’s life for it proved that the Black Prince had both successes and failures throughout his lifetime. The Military and Administrative Leadership of Edward, the Black Prince by Ashley K. Tidwell, B.A. A Thesis Approved by the Department of History ___________________________________ Jeffrey S. Hamilton, Ph.D., Chairperson Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of Baylor University in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts Approved by the Thesis Committee ___________________________________ Jeffrey S. Hamilton, Ph.D., Chairperson ___________________________________ Keith A. Francis, Ph.D. ___________________________________ Julia T. Hejduk, Ph.D. Accepted by the Graduate School August 2008 ___________________________________ J. Larry Lyon, Ph.D., Dean Page bearing signatures is kept on file in the Graduate School. -

What Every Elizabethan Knew

Shakespeare's Histories What the Elizabethans Believed About History "In order to write his plays about English history Shakespeare turned to contemporary history books, called chronicles, particularly those by Edward Hall and Raphael Holinshed. Recounting the past sequentially, these books discussed politics, weather, local events, disasters, and marvelous occurrences like the birth of a baby with two heads. The chronicle accounts of kings, queens, rebellions, battles, wars, councils, and the like entertained as well as informed; they provided a long-running series on the lives of the rich and famous, who happened also to be the royal, the powerful, the good, and the evil. The millions of people today who eagerly read historical novels, watch BBC specials or films like Oliver Stone's JFK, or devour materials on Princess Diana's life and death, would have turned to chronicles in Shakespeare's day. They substituted for our histories, docu-dramas, journals, films, and in some cases, even our soap operas. Chronicles offered the excitements of historical research as well as those of popular non-fiction and fiction. Confronting so rich a record of human achievement and folly, chroniclers often read in English history political and moral truths. Everywhere they saw, or at least said they saw, the evils of dissension and rebellion, for example, or the inevitable workings of divine justice. Shakespeare inherited these thematic focuses as he shaped chronicle materials, often loose, formless, into sharp conflicts between compelling individuals; sometimes he darkened them into tragedy, as in Richard II; sometimes he brightened them into comedy, as in Henry V. -

King Edward III & Queen Philippa of Hainault My 18Th Great Grandparents

Queen Philippa interceding for the Burghers of Calais by J.D. Penrose, (Wikipedia). King Edward III & Queen Philippa of Hainault my 18th Great Grandparents ~ Published on November 26, 2019 Philippa of Hainault (Middle French: Philippe de Hainaut; 24 June[1] c.1310/15[2] – 15 August 1369) was Queen of England as the wife of King Edward III.[3] Edward promised in 1326 to marry her within the following two years.[4] She was married to Edward, first by proxy, when Edward dispatched the Bishop of Coventry "to marry her in his name" in Valenciennes (second city in importance of the county of Hainaut) in October 1327.[5] The marriage was celebrated formally in York Minster on 24 January 1328, some months after Edward's accession to the throne of England. In August 1328, he also fixed his wife's dower.[6] Philippa acted as regent in 1346,[7] when her husband was away from his kingdom, and she often accompanied him on his expeditions to Scotland, France, and Flanders. Philippa won much popularity with the English people for her kindness and compassion, which were demonstrated in 1347 when she successfully persuaded King Edward to spare the lives of the Burghers of Calais. This popularity helped maintain peace in England throughout Edward's long reign. [8] The eldest of her thirteen children was Edward, the Black Prince, who became a renowned military leader. Philippa died at the age of fifty-six from an illness closely related to edema. The Queen's College, Oxford was founded in her honour. (Wikipedia). Currently a student in the MA Eighteenth Century Studies program at the University of York, UK, recently I had the opportunity to read "Acts of Union and Disunion," Linda Colley (p. -

Martin's Notes from the June/July 2017 Visits To

MARLOW SOCIETY HISTORY GROUP. Members of the Marlow Society made visits to three local places of historic interest during 2017. The June visit to Basing Castle introduced us to the ruins of the largest private house in Tudor England, a Royalist house destroyed after a siege in which Oliver Cromwell deployed his heavy artillery to breach the walls. Bricks from the demolished house were recycled and can now be seen in the walls of nearby houses. In contrast the Tudor Great Barn is a staggering fully preserved structure which, in former times, provided storage for the estate’s grain in winter. Try to book a guided walk: ours brought the place to life. The Great Barn The Kitchens In July we went to Frogmore Paper Mill. This is located close to Hemel Hempstead. In it is the world’s oldest mechanised paper mill. At the beginning of the nineteenth century the Fourdrinier brothers acquired a French patent for a mechanised mill, but this did not become viable until its design had been significantly developed into the first useable machine in 1802. Powered by a water wheel, now restored, and with access to the Grand Union Canal, the paper making industry flourished, no doubt in part due to the introduction of the Penny Post in 1840. The business later became part of the John Dickinson Company, then the British Paper Company, and continued in production until 2009. We were shown how to make a sheet of paper by hand and produced our own example. We then saw a Fourdrinier machine in action, turning a “porridge” of recycled paper pulp and water into a roll of paper in four minutes. -

MEDIEVAL TURNING POINTS INFLUENCED by MY ANCESTORS Such As King Alfred the Great

MEDIEVAL TURNING POINTS INFLUENCED BY MY ANCESTORS Such as King Alfred the Great BY DEAN LADD 2013 INTRODUCTION This is a sequel to my manuscript, Medieval Quest, My Ancestors’ Involvement in Royalty Intrigue. The concept for this writing became readily apparent after listening to the newest Great Courses lectures about these turning points in Medieval history and realizing that my ancestors were key persons in many of the covered events. For instance, Eleanor of Aquitaine was one of the most remarkable women of the time, having married two kings and being the mother of two kings. Her son, King John, signed the Magna Carta, which wasn’t generally recognized as an important event until much later. Such turning point events shaped and continue to shake the world today. Medieval Quest was written in the journalistic form of “interviews in the period” with five key women, whereas this manuscript is written as normal history to a much greater research depth. It will include the historical impact of many others, extending back to Charles Martel (688-741). King Alfred the Great (849-899) is shown on the cover page. This is his statue, located where he was buried in Winchester, UK. The number of greats, stated in this manuscript, varies slightly from those in Medieval Quest. My following royalty ancestors were key participants in Medieval turning points: Joan Plantagenet, called “The Fair Maid of Kent” (1335-1385 King Edward I of England, called “Long Shanks” (1239-1307) King John of England, called “Lackland” (1166-1216) Eleanor of Aquitaine (1122-1203) William 1 of England, called “The Conqueror” (1027-1087) Saint Margaret of Scotland (1045-1093) Saint Vladimir of Kiev, Called “The Great” (958-1015) Saint Olga of Kiev (890-969) King Alfred the Great of England (849-899) Rurik the Viking (830-879) Charlemagne of the Franks (742-813) Charles Martel of the Franks, Called “The Hammer” (686-741). -

Answers to History Quiz 1

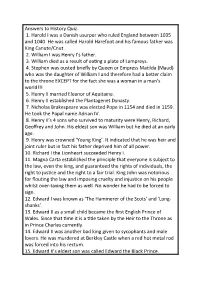

Answers to History Quiz. 1. Harold I was a Danish usurper who ruled England between 1035 and 1040. He was called Harold Harefoot and his famous father was King Canute/Cnut. 2. William I was Henry I’s father. 3. William died as a result of eating a plate of Lampreys. 4. Stephen was ousted briefly by Queen or Empress Matilda (Maud) who was the daughter of William I and therefore had a better claim to the throne EXCEPT for the fact she was a woman in a man’s world!!! 5. Henry II married Eleanor of Aquitaine. 6. Henry II established the Plantagenet Dynasty. 7. Nicholas Brakespeare was elected Pope in 1154 and died in 1159. He took the Papal name Adrian IV. 8. Henry II’s 4 sons who survived to maturity were Henry, Richard, Geoffrey and John. His eldest son was William but he died at an early age. 9. Henry was crowned ‘Young King’. It indicated that he was heir and joint ruler but in fact his father deprived him of all power. 10. Richard I the Lionheart succeeded Henry I. 11. Magna Carta established the principle that everyone is subject to the law, even the king, and guaranteed the rights of individuals, the right to justice and the right to a fair trial. King John was notorious for flouting the law and imposing cruelty and injustice on his people whilst over-taxing them as well. No wonder he had to be forced to sign. 12. Edward I was known as ‘The Hammerer of the Scots’ and ‘Long- shanks’.