WINGATE Final.Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Janet Cardiff & George Bures Miller

JANET CARDIFF & G. B. MILLER page 61 JANET CARDIFF & GEORGE BURES MILLER Live & work in Grindrod, Canada Janet Cardiff Born in 1957, Brussels, Canada George Bures Miller Born in 1960, Vegreville, Canada AWARDS 2021 Honorary degrees, NSCAD (Nova ScoOa College of Art & Design) University, Halifax, Canada 2011 Käthe Kollwitz Prize, Akademie der Künste, Berlin, Germany 2004 Kunstpreis der Stadt Jena 2003 Gershon Iskowitz Prize 2001 Benesse Prize, 49th Venice Biennale, Venice, Italy Biennale di Venezia Special Award, 49th Venice Biennale, Venice, Italy 2000 DAAD Grant & Residency, Berlin, Germany SELECTED INDIVIDUAL EXHIBITIONS 2019 Janet Cardiff & George Bures Miller, Museo de Arte Contemporaneo de Monterrey, Monterrey, Mexico 2018-2019 Janet Cardiff & Geroge Bures Miller: The Instrument of Troubled Dreams, Oude Kerk, Amsterdam, The Netherlands 2018 Janet Cardiff & George Bures Miller: The Poetry Machine and other works, Fraenkel Gallery, FRAENKELGALLERY.COM [email protected] JANET CARDIFF & G. B. MILLER page 62 San Francisco, CA FOREST… for a thousand years, UC Santa Cruz Arboretum and Botanic Garden, Santa Cruz, CA Janet Cardiff & George Bures Miller: Two Works, SCAD Art Museum, Savannah, GA 2017-18 Janet Cardiff & George Bures Miller, 21st Century Museum of Contemporary Art, Kanazawa, Japan 2017 Janet Cardiff: The Forty Part Motet, Switch House at Tate Modern, London, England; Nelson Atkins Museum of Art, Kansas City, MO; Mobile Museum of Art, Mobile, AL; Auckland Castle, Durham, England; TRAFO Center for Contemporary Art, Szczecin, Poland -

JASPER JOHNS 1930 Born in Augusta, Georgia Currently Lives

JASPER JOHNS 1930 Born in Augusta, Georgia Currently lives and works in Connecticut and Saint Martin Education 1947-48 Attends University of South Carolina 1949 Parsons School of Design, New York Selected Solo Exhibitions 2009 Focus: Jasper Johns, The Museum of Modern Art, New York 2008 Jasper Johns: Black and White Prints, Bobbie Greenfield Gallery, Santa Monica, California Jasper Johns: The Prints, The Madison Museum of Contemporary Art, Madison, Wisconsin Jasper Johns: Drawings 1997 – 2007, Matthew Marks Gallery, New York Jasper Johns: Gray, Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York 2007 Jasper Johns: From Plate to Print, Yale University Art Gallery, New Haven Jasper Johns: Gray, Art Institute of Chicago; Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York Jasper Johns-An Allegory of Painting, 1955-1965, National Gallery of Art, Washington, DC; Kunstmuseum Basel, Switzerland States and Variations: Prints by Jasper Johns, National Gallery of Art, Washington, D.C. 2006 Jasper Johns: From Plate to Print, Yale University Art Gallery Jasper Johns: Usuyuki, Craig F. Starr Associates, New York 2005 Jasper Johns: Catenary, Matthew Marks Gallery, New York Jasper Johns: Prints, Amarillo Museum of Art, Amarillo, Texas 2004 Jasper Johns: Prints From The Low Road Studio, Leo Castelli Gallery, New York 2003 Jasper Johns: Drawings, The Menil Collection, Houston, Texas Jasper Johns: Numbers, Cleveland Museum of Art, Cleveland; Los Angeles County Museum of Art Past Things and Present: Jasper Johns since 1983, Walker Art Center Minneapolis; Greenville County Museum of -

Drifttilskud Museer 2021

MUSEUMSNAVN ÅR TILSKUD I ALT Arbejdermuseet 2021 5.808.555 ARKEN Museum for Moderne Kunst 2021 31.687.053 ARoS Aarhus Kunstmuseum 2021 2.080.556 Billund Museum 2021 1.125.109 Bornholms Kunstmuseum 2021 1.012.073 Bornholms Museum 2021 1.512.073 Brandts 2021 2.258.478 Danmarks Tekniske Museum 2021 5.983.863 Dansk Jødisk Museum 2021 3.012.073 De Danske Kongers Kronologiske Samling 2021 9.016.901 De Kulturhistoriske Museer i Holstebro Kommune 2021 5.651.279 Den Gamle By Danmarks Købstadmuseum 2021 8.632.807 Designmuseum Danmark 2021 15.671.064 Energimuseet 2021 1.915.737 Esbjerg Kunstmuseum 2021 1.147.197 Faaborg Museum 2021 1.012.073 Fiskeri-& Søfartsmuseet 2021 4.754.230 Frederiksberg Museerne 2021 1.012.073 Fuglsang Kunstmuseum 2021 3.717.237 Furesø Museer 2021 1.012.073 Gammel Estrup - Herregårdsmuseet 2021 3.863.355 Give-Egnens Museum 2021 1.012.073 Glud Museum 2021 1.589.797 Greve Museum 2021 2.063.478 HEART Herning Museum Of Contemporary Art 2021 1.423.527 Helsingør Kommunes Museer 2021 1.012.073 Historie & Kunst 2021 1.946.741 Holstebro Kunstmuseum 2021 1.399.756 Industrimuseet Frederiks Værk 2021 1.012.073 Industrimuseet Horsens 2021 1.218.066 J.F. Willumsens Museum 2021 1.100.493 Kastrupgårdsamlingen 2021 1.012.073 Kroppedal Museum 2021 5.155.135 Kunsten Museum Of Modern Art, Aalborg 2021 2.566.687 Kunstmuseet Trapholt 2021 2.132.633 KØN – Gender Museum Denmark* 2021 517.207 KØS - Museum For Kunst I Det Offentlige Rum 2021 2.246.968 Langelands Museum 2021 1.317.613 Lemvig Museum 2021 1.163.607 Limfjordsmuseet 2021 1.100.204 Louisiana -

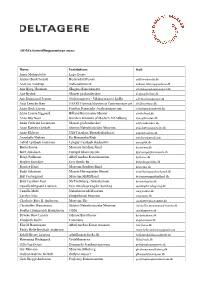

ODM's Formidlingsseminar 2020 Navn: Institution: Amer Mahmutovis

ODM's formidlingsseminar 2020 Navn: Institution: Mail: Amer Mahmutovis Lego House Anders Bank Lodahl Rudersdal Museer [email protected] Andreas Tolstrup Nationalmuseet [email protected] Ane Bjerg Thomsen Skagens Kunstmuseer [email protected] Ane Bysted Museet på Sønderskov [email protected] Ane Damgaard Jepsen Østfynsmuseer - Vikingemuseet Ladby [email protected] Anja Lemcke Stær HEART Herning Museum of Contemporary art [email protected] Anna Back Larsen Fonden Danmarks Jernbanemuseum [email protected] Anna Louise Siggaard Billund Kommunes Museer [email protected] Anne Bay Noer Kunsten Museum of Modern Art Aalborg [email protected] Anne Cathrine Lorentzen Museet på Sønderskov [email protected] Anne Katrine Gjerløff Statens Naturhistoriske Museum [email protected] Anne Kleberg ULF I Aarhus/Børnekultuthuset [email protected] Annebelle Nielsen En Hemmelig Klub [email protected] Astrid Lystbæk Andersen Lyngby-Taarbæk Stadsarkiv [email protected] Bente Sonne Museum Sønderjylland [email protected] Berit Jakobsen Hempel Glasmuseum [email protected] Birgit Pedersen ARoS Aarhus Kunstmuseum [email protected] Birgitte Damkjer Den Gamle By [email protected] Birgitte Hjort Museum Sønderjylland [email protected] Bodil Jakobsen Museet Herregården Hessel [email protected] Brit Vestergaard Museum Midtjylland [email protected] Britt Caroline Juul Ny Trelleborg - Sekretariatet [email protected] Camilla Klitgaard Laursen Den Hirschsprungske Samling [email protected] Camilla Mehl Naturhistorisk Museum [email protected] Carsten Niss Østsjællands -

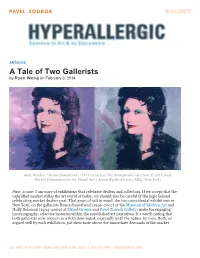

A Tale of Two Gallerists by Ryan Wong on February 3, 2014

ARTICLES A Tale of Two Gallerists by Ryan Wong on February 3, 2014 Andy Warhol, “Ileana Sonnabend” (1973) (courtesy The Sonnabend Collection, © 2013 Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts / Artists Rights Society [ARS], New York) First, a note: I am wary of exhibitions that celebrate dealers and collectors. If we accept that the unbridled market stifles the art world of today, we should also be careful of the logic behind celebrating market dealers past. That grain of salt in mind, the two coincidental exhibitions in New York, on the gallerists Ileana Sonnabend (1914–2007) at the Museum of Modern Art and Holly Solomon (1934–2002) at Mixed Greens and Pavel Zoubok Gallery, make for engaging historiography, selective histories within the established art narratives. It’s worth noting that both gallerists were women in a field dominated, especially until the 1980s, by men. Both, as argued well by each exhibition, put their taste above the immediate demands of the market. The publicity image for each exhibition is a portrait of the gallerist by Warhol. For Solomon, it is a vertical photo booth series from 1983, Solomon clearly enjoying herself as she mugs for each shot. In Sonnabend’s 1973 diptych portrait, Warhol applied his signature mess of zig-zags around the contours of the silkscreened image. The reliance on Warhol is no coincidence: his alchemical touch makes these women familiar, even to those who don’t frequent the back rooms of the art world. Hooray for Hollywood! at Mixed Greens opens with a room full of portraits of the gallerist by artists from Robert Mapplethrope to William Wegman to Christo. -

Katalog 2008.Pdf

Billedkunstner Anders Visti Åbne værksteder • 4.-5. oktober ’08,kl. 11-17 • www.midtikunsten.dk ÅrhusÅrhuhus Udgiver: Region Midtjylland Regional Udvikling Oplevelsesøkonomi og landdistrikter Skottenborg 26 8800 Viborg Tlf.: 8728 5000 Mail: [email protected] www.midtikunsten.dk Lay-out: Grafi sk Service • 4400-08-125 Tryk: Unitryk Forsideillustration: Billedkunstner Anders Visti ISBN 87-7788-176-1 Oplag: 14.000 Viborg 2008 Indhold Forord ............................................................................................... 4 Favrskov ........................................................................................... 6 Hedensted ....................................................................................... 8 Herning ............................................................................................ 9 Holstebro ......................................................................................... 10 Horsens ............................................................................................ 11 Ikast-Brande ................................................................................... 14 Lemvig .............................................................................................. 16 Norddjurs ........................................................................................ 19 Odder ................................................................................................ 22 Randers ........................................................................................... -

Jeppe Hein Full

JEPPE HEIN BORN 1974 Copenhagen Lives and works in Copenhagen / Berlin EDUCATION 1999 Städelschule, Hochschule für Bildende Künste, Frankfurt am Main 1997 Royal Danish Academy of Arts, Copenhagen SOLO EXHIBITIONS 2021 “Space in Action. Action in Space”, Das Lenbachhaus, Munich, Germany “Your Light is the Light in Me”, Galleri Nicolai Wallner, Copenhagen, Denmark “kunst findet stadt - Jeppe Hein”, Kurgarten Baden-Baden, Germany “YOU MAKE ME SHINE”, KÖNIG SEOUL, MCM HAUS, Seoul, Korea 2020 “All Your Wishes”, Terminal B At La Guardia Airport, Queens, NY “Nothing is as it appears”, KÖNIG GALERIE, St. Agnes, Chapel, Berlin, Germany “Circular Appearing Rooms”, Bundeskunsthalle Bonn, Germany “Today I feel like”, Schirn Kunsthalle, Frankfurt, Germany 2019 “Breathe With Me”, UN Headquarters and Central Park, New York, NY “I AM WITH YOU”, 303 Gallery, New York, NY “Behind Hein”, König Galerie, Dessauer Strasse, Berlin, Germany “Change Yourself”, Politiken Forhal, Copenhagen, Denmark “Intervention Impact”, artconnexion, Lillie, France “Jeppe Hein”, SCAI Park, Tokyo, Japan 2018 “IN IS THE ONLY WAY OUT”, Cisternerne, Copenhagen, Denmark “Inhale – Hold – Exhale”, Kunstmuseum, Thun, Switzerland 2017 “Don’t Expect Anything – Be Open to Everything”, König Galerie, Berlin, Germany “Your Way”, Château La Coste, Le Puy-Sainte-Réparade, France “Distance”, Sørlandets Kunstmuseum, Kristiansand, Denmark “Festival of Love, Modified Social Benches NY”, Southbank Centre, Festival Terrace & Queens Walk, London, UK “At sanse verden i dig selv”, Museet for Religiøs -

ANDY WARHOL New York, NY 10014

82 Gansevoort Street ANDY WARHOL New York, NY 10014 p (212) 966 - 6675 Born 1928, Pittsburgh, PA allouchegallery.com Died 1987, New York City, NY BFA Pictorial Design Carnegie Mellon University SELECTED SOLO EXHIBITIONS 2016 Andy Warhol: Shadows, Guggenheim Bilbao, Spain 2015 Andy Warhol: Works from the Hall Collection, Ashmolean Museum, Oxford, England 2015 Yes! Yes! Yes! Warholmania in Munich, Museum Brandhorst, Munich, Germany 2015 Capturing Fame: Photographs and Prints by Andy Warhol, Richard E, Peeler Art Center, Depauw University, Greencastle, IN 2015 Warhol: Myths and Legends from the Cochran Collection, Art Museum of South Texas, Corpus Christie, TX 2015 Transmitting Andy Warhol, Tate Liverpool, Liverpool, England 2014 Andy Warhol: 1950s Drawings, Anton Kern Gallery, New York, NY 2014 Transmitting Andy Warhol, Tate Liverpool, Liverpool, England 2014 Andy Warhol: Death and Disaster, Kunstsammlungen Chemnitz, Germany 2014 Andy Warhol: Shadows, The Museum of Contemporary Art, Los Angeles, CA 2014 Warhol: Art. Fame. Mortality, The Salvador Dali Museum, St. Petersburg, FL 2014 Andy Warhol’s 13 Most Wanted Men and the 1964 World’s Fair, Queens Museum of Art, New York, NY 2014 Andy Warhol: 15 Minutes Eternal, Mori Art Museum, Tokyo, Japan 2013 Andy Warhol: Toy Paintings, Tel Aviv Museum of Art, Tel Aviv, Israel 2012 Warhol Headlines, National Gallery of Art, Washington, D.C 2011 Andy Warhol and Elizabeth Taylor, Gagosian Gallery, New York, NY 2010 Andy Warhol: Motion Pictures, Museum of Modern Art, New York, NY 2007 Andy Warhol Disaster Prints, Kampa Museum, Prague, Czech Republic 2006 Andy Warhol Campbell’s Soup Cans, Museum of Contemporary Art, Los Angeles, CA 2000 Women of Warhol: Marilyn, Liz & Jackie, C & M Arts, New York, NY 1996 Rorschach Paintings, Gagosian Gallery, New York, NY 1992 Andy Warhol Polaroids 1971 – 1986, Anthony d’Offay Gallery, London, England 1992 Heaven and Hell Are Just One Breath Away! Gagosian Gallery, New York, NY 1989 Andy Warhol Retrospective, Museum Ludwig, Cologne, Germany 1988 Andy Warhol: Cars, The Solomon R. -

Oral History Interview with Leo Castelli

Oral history interview with Leo Castelli Archives of American Art 750 9th Street, NW Victor Building, Suite 2200 Washington, D.C. 20001 https://www.aaa.si.edu/services/questions https://www.aaa.si.edu/ Table of Contents Collection Overview ........................................................................................................ 1 Administrative Information .............................................................................................. 1 General............................................................................................................................. 2 Scope and Contents........................................................................................................ 1 Scope and Contents........................................................................................................ 1 Biographical / Historical.................................................................................................... 1 Names and Subjects ...................................................................................................... 2 Container Listing ...................................................................................................... Oral history interview with Leo Castelli AAA.castel69may Collection Overview Repository: Archives of American Art Title: Oral history interview with Leo Castelli Identifier: AAA.castel69may Date: 1969 May 14-1973 June 8 Creator: Castelli, Leo (Interviewee) Cummings, Paul (Interviewer) Extent: 194 Pages (Transcript) Language: English -

James Rosenquist - Select Chronology

James Rosenquist - Select Chronology THE EARLY YEARS 1933 Born November 29 in Grand Forks, North Dakota. Parents Louis and Ruth Rosenquist, oF Swedish and Norwegian descent. Family settles in Minneapolis, Minnesota in 1942. 1948 Wins junior high school scholarship to study art at the Minneapolis School of Art at the Minneapolis Art Institute. 1952-54 Attends the University oF Minnesota, and studies with Cameron Booth. Visits the Art Institute oF Chicago to study old master and 19th-century paintings. Paints storage bins, grain elevators, gasoline tanks, and signs during the summer. Works For General Outdoor Advertising, Minneapolis, and paints commercial billboards. 1955 Receives scholarship to the Art Students League, New York, and studies with Morris Kantor, George GrosZ, and Edwin Dickinson. 1957-59 Becomes a member oF the Sign, Pictorial and Display Union, Local 230. Employed by A.H. Villepigue, Inc., General Outdoor Advertising, Brooklyn, New York, and ArtkraFt Strauss Sign Corporation. Paints billboards in the Times Square area and other locations in New York. 1960s 1960 Quits working For ArtkraFt Strauss Sign Corporation. Rents a loFt at 3-5 Coenties Slip, New York; neighbors include the painters Jack Youngerman, Ellsworth Kelly, Agnes Martin, Robert Indiana, Lenore Tawney, Robert Rauschenberg, Jasper Johns, Barnett Newman, and the poet Oscar Williamson. 1961 Paints Zone (1960-61), his First studio painting to employ commercial painting techniques and Fragmented advertising imagery. 1962 Has first solo exhibition at the Green Gallery, New York, which he joined in 1961. Early collectors include Robert C. Scull, Count Giuseppe PanZa di Biumo, Richard Brown Baker, and Burton and Emily Tremaine. -

Review: 'Peter Saul: from Pop to Punk,' a Firebrand Willing to Offend

Smith, Roberta, “Review: ‘Peter Saul: From Pop to Punk,’ a Firebrand Willing to Offend,” The New York Times, March 12, 2015. Review: ‘Peter Saul: From Pop to Punk,’ a Firebrand Willing to Offend The New York art dealer Ileana Sonnabend once avowed — somewhat self- servingly — that the best collectors are people in her line of work. Every so often the evidence mounts, as it does with “Peter Saul: From Pop to Punk”at Venus Over Manhattan. This poetically named art gallery established in 2012 by Adam Lindemann, a collector and occasional writer for The New York Observer, does not represent artists, but it regularly stages relevant exhibitions, and this is one of his best. The show consists of a riveting clutch of 16 paintings and five large drawings from 1962 to 1973, all from the collection of Mr. Saul’s longtime dealer, Allan Frumkin (1927-2002). They shed special light on a crucial period in the development of this firebrand painter and lifelong abstract art denier, who, despite quite a bit of exposure, has yet to receive his due. Mr. Saul, who was born in San Francisco in 1934, attended what is now the San Francisco Art Institute and Washington University in St. Louis before heading to Europe in 1956. There he scraped by, going to museums and making paintings, first in the Netherlands, then Paris — where he had an influential encounter with Mad Magazine in a bookstore and also met Mr. Frumkin — and finally Rome. During the years covered by this show, Mr. Saul made an Abstract Expressionist version of Pop Art; returned to the United States in 1964; relinquished oil paint for acrylic; and quickly evolved his rather tightly wound fluorescent “wild style” concoctions of figures that are at once savage political cartoons and beautiful if 980 MADISON AVENUE NEW YORK, NY 10075 212.980.0700 VENUSOVERMANHATTAN.COM disconcerting paintings. -

MUSEUMSNAVN ÅR TILSKUD IALT Kvindemuseet 2019 41.494,31

MUSEUMSNAVN ÅR TILSKUD_IALT Kvindemuseet 2019 41.494,31 Naturhistorisk Museum 2019 332.707,41 Ærø Museum 2019 1.005.000,00 Bornholms Kunstmuseum 2019 1.015.000,00 Faaborg Museum 2019 1.015.000,00 Frederiksberg Museerne 2019 1.015.000,00 Furesø Museer 2019 1.015.000,00 Give-Egnens Museum 2019 1.015.000,00 Helsingør Kommunes Museer 2019 1.015.000,00 Industrimuseet Frederiks Værk 2019 1.015.000,00 Kastrupgårdsamlingen 2019 1.015.000,00 Marstal Søfartsmuseum 2019 1.015.000,00 Middelfart Museum 2019 1.015.000,00 Museum Amager 2019 1.015.000,00 Museum Skanderborg 2019 1.015.000,00 Vendsyssel Kunstmuseum 2019 1.026.174,70 Museum Jorn 2019 1.066.345,87 Randers Kunstmuseum 2019 1.066.345,87 Skovgaard Museet 2019 1.076.429,01 Museerne i Brønderslev Kommune 2019 1.079.599,45 Limfjordsmuseet 2019 1.100.808,28 J.F. Willumsens Museum 2019 1.101.088,81 Læsø Museum 2019 1.104.908,30 Vejen Kunstmuseum 2019 1.109.563,00 Nivaagaards Malerisamling 2019 1.119.105,89 Svendborg Museum 2019 1.119.829,83 Billund Museum 2019 1.125.056,44 Esbjerg Kunstmuseum 2019 1.146.562,38 Lemvig Museum 2019 1.162.539,20 Ribe Kunstmuseum 2019 1.208.018,84 Museum Vestfyn 2019 1.213.752,31 Industrimuseet Horsens 2019 1.215.563,48 Vesthimmerlands Museum 2019 1.225.910,54 Langelands Museum 2019 1.312.485,84 Øhavsmuseet Faaborg 2019 1.317.485,84 Struer Museum 2019 1.330.464,13 Holstebro Kunstmuseum 2019 1.392.463,66 HEART Herning Museum Of Contemporary Art 2019 1.415.607,90 Museum Mors 2019 1.416.636,03 Viborg Museum 2019 1.453.657,49 Museet For Samtidskunst 2019 1.565.324,89 Glud