By Jost Thöne Verlag —Pdf Sample—

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Messiah Notes.Indd

Take One... The Messiah Violin Teacher guidance notes The Messiah Violin is on display in A zoomable image of the violin is available Gallery 39, Music and Tapestry. on our website. Visit www.ashmolean.org/education/ Starting Questions The following questions may be useful as a starting point for thinking about the Messiah violin and developing speaking and listening skills with your class. • What materials do you think this violin is made from? • Why do you think this violin is in a museum? • Where do you think it might come from? • What kind of person do you think would have owned this violin? • Who could have made it? • Does the violin look like it has been played a lot or does it look brand new? • How old do you think the violin could be? • If I told you that nobody is allowed to play this violin do you feel about that? These guidance notes are designed to help you use the Ashmolean’s Messiah violin as a focus for cross-curricular teaching and learning. A visit to the Ashmolean Museum to see your chosen object offers your class the perfect ‘learning outside the classroom’ opportunity. Background Information Italy - a town that was already famous for its master violin makers. The new styles of violins and cellos that The Object he developed were remarkable for their excellent tonal quality and became the basic design for many TThe Messiah violin dates from Stradivari’s ‘golden modern versions of the instruments. period’ of around 1700 - 1725. The violin owes Stradivari’s violins are regarded as the fi nest ever its fame chiefl y to its fresh appearance due to the made. -

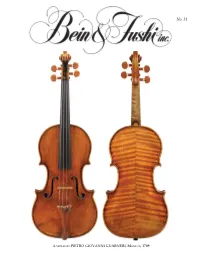

B&F Magazine Issue 31

No. 31 A VIOLIN BY PIETRO GIOVANNI GUARNERI, MANTUA, 1709 superb instruments loaned to them by the Arrisons, gave spectacular performances and received standing ovations. Our profound thanks go to Karen and Clement Arrison for their dedication to preserving our classical music traditions and helping rising stars launch their careers over many years. Our feature is on page 11. Violinist William Hagen Wins Third Prize at the Queen Elisabeth International Dear Friends, Competition With a very productive summer coming to a close, I am Bravo to Bein & Fushi customer delighted to be able to tell you about a few of our recent and dear friend William Hagen for notable sales. The exquisite “Posselt, Philipp” Giuseppe being awarded third prize at the Guarneri del Gesù of 1732 is one of very few instruments Queen Elisabeth Competition in named after women: American virtuoso Ruth Posselt (1911- Belgium. He is the highest ranking 2007) and amateur violinist Renee Philipp of Rotterdam, American winner since 1980. who acquired the violin in 1918. And exceptional violins by Hagen was the second prize winner Camillo Camilli and Santo Serafin along with a marvelous of the Fritz Kreisler International viola bow by Dominique Peccatte are now in the very gifted Music Competition in 2014. He has hands of discerning artists. I am so proud of our sales staff’s Photo: Richard Busath attended the Colburn School where amazing ability to help musicians find their ideal match in an he studied with Robert Lipsett and Juilliardilli d wherehh he was instrument or bow. a student of Itzhak Perlman and Catherine Cho. -

Carla Shapreau-CV

Carla Shapreau Department of Music 104 Curator, Ansley K. Salz Collection, Department of Music Morrison Hall #1200 Lecturer, School of Law University of California Senior Fellow, Institute of European Studies Berkeley, CA 94720-2316 University of California, Berkeley +1 (510) 849-0777 Research website: the Lost Music Project [email protected] _______________________________________________________________________________ Curriculum Vitae Academic Appointments and Affiliations • Curator, Salz Collection of Stringed Instruments, Department of Music, University of California, Berkeley, 2015-present • Lecturer, Berkeley School of Law, University of California, Berkeley, Art and Cultural Property Law, January 2010-present • Senior Fellow, University of California, Berkeley, Institute of European Studies (2014- present) (Research Associate 2011-2013, Visiting Scholar 2007-2010) Awards/Grants • 2018, National Endowment for the Humanities Fellowship Grant, European History: Orpheus Lost: The Nazi-Era Plunder of Music in Europe • 2017, France-Berkeley Fund grant: “The Economic, Social and Political World of Violins in the Pre-War and World War II Eras: Bridging the Archival Gap between the Musée de la Musique and the Smithsonian Institution Collections” • 2015, Claude V. Palisca Award, American Musicological Society for The Ferrell- Vogüé Machaut Manuscript, with co-authors Lawrence Earp and Domenic Leo • 2011, Austrian Marshall Plan Foundation grant: "Austria: Musical Expropriations During the Nazi Era and 21st Century Ramifications" • 2011, -

Antonio Stradivari "Servais" 1701

32 ANTONIO STRADIVARI "SERVAIS" 1701 The renowned "Servais" cello by Stradivari is examined by Roger Hargrave Photographs: Stewart Pollens Research Assistance: Julie Reed Technical Assistance: Gary Sturm (Smithsonian Institute) In 184.6 an Englishman, James Smithson, gave the bines the grandeur of the pre‑1700 instrument with US Government $500,000 to be used `for the increase the more masculine build which we could wish to and diffusion of knowledge among men.' This was the have met with in the work of the master's earlier beginning of the vast institution which now domi - years. nates the down‑town Washington skyline. It includes the J.F. Kennedy Centre for Performing Arts and the Something of the cello's history is certainly worth National Zoo, as well as many specialist museums, de - repeating here, since, as is often the case, much of picting the achievements of men in every conceiv - this is only to be found in rare or expensive publica - able field. From the Pony Express to the Skylab tions. The following are extracts from the Reminis - orbital space station, from Sandro Botticelli to Jack - cences of a Fiddle Dealer by David Laurie, a Scottish son Pollock this must surely be the largest museum violin dealer, who was a contemporary of J.B. Vuil - and arts complex anywhere in the world. Looking laume: around, one cannot help feeling that this is the sort While attending one of M. Jansen's private con - of place where somebody might be disappointed not certs, I had the pleasure of meeting M. Servais of Hal, to find the odd Strad! And indeed, if you can manage one of the most renowned violoncellists of the day . -

Some Misconceptions About the Baroque Violin

Pollens: Some Misconceptions about the Baroque Violin Some Misconceptions about the Baroque Violin Stewart Pollens Copyright © 2009 Claremont Graduate University Much has been written about the baroque violin, yet many misconceptions remain²most notably that up to around 1750 their necks were universally shorter and not angled back as they are today, that the string angle over the bridge was considerably flatter, and that strings were of narrower gauge and under lower tension.1 6WUDGLYDUL¶VSDWWHUQVIRUFRQVWUXFWLQJQHFNVILQJHUERDUGVEULGJHVDQG other fittings preserved in the Museo Stradivariano in Cremona provide a wealth of data that refine our understanding of how violins, violas, and cellos were constructed between 1666- 6WUDGLYDUL¶V\HDUV of activity). String tension measurements made in 1734 by Giuseppe Tartini provide additional insight into the string diameters used at this time. The Neck 7KHEDURTXHYLROLQ¶VWDSHUHGQHFNDQGZHGJH-shaped fingerboard became increasingly thick as one shifted from the nut to the heel of the neck, which required the player to change the shape of his or her hand while moving up and down the neck. The modern angled-back neck along with a thinner, solid ebony fingerboard, provide a nearly parallel glide path for the left hand. This type of neck and fingerboard was developed around the third quarter of the eighteenth century, and violins made in earlier times (including those of Stradivari and his contemporaries) were modernized to accommodate evolving performance technique and new repertoire, which require quicker shifts and playing in higher positions. 7KRXJK D QXPEHU RI 6WUDGLYDUL¶V YLROD DQG FHOOR QHFN SDWWHUQV DUH SUHVHUYHG LQ WKH 0XVHR Stadivariano, none of his violin neck patterns survive, and the few original violin necks that are still mounted on his instruments have all been reshaped and extended at the heel so that they could be mortised into the top block. -

Inventario (1

INVENTARIO (1 - 200) 1 Scatola contenente tre fascicoli. V. segn. 1 ELETTRICE PALATINA ANNA MARIA LUISA DE’ MEDICI 1 Lettere di auguri natalizi all’elettrice palatina Anna Maria Luisa de’ Medici di: Filippo Acciaiuoli, cc.2-4; Faustina Acciaiuoli Bolognetti, cc.5-7; Isabella Acquaviva Strozzi, cc.8-10; cardinale Alessandro Albani, cc.11-13; Fi- lippo Aldrovandi Marescotti, cc.14-16; Maria Vittoria Altoviti Cor- sini, cc.17-19; Achille Angelelli, cc.20-23; Roberto Angelelli, cc.24- 26; Dorothea Angelelli Metternich, cc.27-29; Lucrezia Ansaldi Le- gnani, cc.30-32; Giovanni dell’Aquila, cc.33-35; duchessa Douariere d’Arenberg, con responsiva, cc.36-40; governatore di Grosseto Cosimo Bagnesi, cc.41-43; Andrea Barbazzi, cc.44-46; segretario della Sacra Consulta Girolamo de’ Bardi, cc.47-49; cardinale [Lodovico] Belluga, cc.50-52; Lucrezia Bentivoglio Dardinelli, cc.53-55; Maria Bergonzi Ra- nuzzi, cc.56-58; cardinale Vincenzo Bichi, cc.59-61; «re delle Due Si- Nell’inventario, il numero del pezzo è posto al centro in neretto. Alla riga successiva, in cor- cilie» Carlo VII, con responsiva, cc.62-66; vescovo di Borgo Sansepol- sivo, sono riportate la descrizione estrinseca del volume, registro o busta con il numero com- cro [Raimondo Pecchioli], cc.67-69; Camilla Borgogelli Feretti, cc.70- plessivo dei fascicoli interni e le vecchie segnature. Quando il nesso contenutistico fra i do- 72; Cosimo Bourbon del Monte, cc.73-75; baronessa de Bourscheidt, cumenti lo rendeva possibile si è dato un titolo generale - in maiuscoletto - a tutto il pezzo, con responsiva, cc.76-79; vescovo di Cagli [Gerolamo Maria Allegri], o si è trascritto, tra virgolette in maiuscoletto, il titolo originale. -

“Triennale” Violin Making Competition Antonio Stradivari Cremona September 4Th - October 11Th 2015 Exhibition from September 24Th

14th International “Triennale” Violin Making Competition Antonio Stradivari Cremona September 4th - October 11th 2015 Exhibition from September 24th www.museodelviolino.org Graphic designer: Corrado Testa Graphic designer: Corrado regulation Dear Maestros, 1 the 14th International Triennale Violin Making Competition to be held in September 2015 will be of special importance. On the one hand, it will coincide with the Universal Exposition Milano EXPO 2015 in which Cremona aims at playing a leading role and being a pole of attraction for a great number of visitors. Cremonese violin making will in fact be signifi cantly represented in the Italian Pavilion; the winners of the Competition will be presented at the Pavilion the day before the offi cial awards ceremony that will be held, as is tradition, in the beautiful Teatro Ponchielli. On the other hand, it will be the fi rst Competition to be disputed after the opening of the Museo del Violino, a museum where the history of fi ve hundred years of Cremonese violin making is illustrated in a direct and fascinating way. The last room of the exhibition 2 is especially dedicated to contemporary violin making and the history of the Triennale Competition of Cremona. All the gold medal winning instruments are displayed here, in the same place as the great masterpieces of the past made by Stradivari, Amati and Guarneri, just to mention the main ones. We believe this to be a great honour for those makers who were awarded fi rst prize in this Competition and, at the same time, a great incentive to participate with enthusiasm in a contest which is universally known as “the Olimpics of Violin Making” for its reputation, number of entrants and the quality of selected instruments. -

Syrinx (Debussy) Body and Soul (Johnny Green)

Sound of Music How It Works Session 5 Musical Instruments OLLI at Illinois Hurrian Hymn from Ancient Mesopotamian Spring 2020 Musical Fragment c. 1440 BCE D. H. Tracy Sound of Music How It Works Session 5 Musical Instruments OLLI at Illinois Shadow of the Ziggurat Assyrian Hammered Lyre Spring 2020 (Replica) D. H. Tracy Sound of Music How It Works Session 5 Musical Instruments OLLI at Illinois Hymn to Horus Replica Ancient Lyre Spring 2020 Based on Trad. Eqyptian Folk Melody D. H. Tracy Sound of Music How It Works Session 5 Musical Instruments OLLI at Illinois Roman Banquet Replica Kithara Spring 2020 Orig Composition in Hypophrygian Mode D. H. Tracy Sound of Music How It Works Session 5 Musical Instruments OLLI at Illinois Spring 2020 D. H. Tracy If You Missed a Session…. • PDF’s of previous presentations – Also other handout materials are on the OLLI Course website: http://olli.illinois.edu/downloads/courses/ The Sound of Music Syllabus.pdf References for Sound of Music OLLI Course Spring 2020.pdf Smartphone Apps for Sound of Music.pdf Musical Scale Cheat Sheet.pdf OLLI Musical Scale Slider Tool.pdf SoundOfMusic_1 handout.pdf SoM_2_handout.pdf SoM_3 handout.pdf SoM_4 handout.pdf 2/25/20 Sound of Music 5 6 Course Outline 1. Building Blocks: Some basic concepts 2. Resonance: Building Sounds 3. Hearing and the Ear 4. Musical Scales 5. Musical Instruments 6. Singing and Musical Notation 7. Harmony and Dissonance; Chords 8. Combining the Elements of Music 2/25/20 Sound of Music 5 7 Chicago Symphony Orchestra (2015) 2/25/20 Sound of Music -

Media Information 2020

MEDIA INFORMATION 2020 THE STRAD DIRECTORY 2020 DIRECTORY DIRECTORY 2020 ESSENTIAL REFERENCE FOR THE STRING INDUSTRY In association with Roderich Paesold – Germany Meisterwerkstätten für feine Streichinstrumente & Bögen seit 1848 WWW.THESTRAD.COM WWW.THESTRAD.COM 2020 EDITION £20.00 US$30.00 €25.00 2020 STRING COURSES INTERNATIONAL COURSES FOR STRING PLAYERS AND MAKERS Supplement to The Strad January 2020 PUBLISHING READERSHIP PRINT RATES PRINT SPECS DIRECTORY DIGITAL RECRUITMENT SCHEDULE THE STRAD PORTFOLIO The voice of the string world since May 1890, The Strad reaches an influential audience of professionals and amateurs, experts and enthusiasts of all stringed instruments played with a bow. THE MAGAZINE The Strad is the only monthly magazine for stringed instruments with a truly international audience, 130-year heritage and a proud reputation for delivering the highest quality editorial content. THE STRAD SUPPLEMENTS DIRECTORY 2020 DIRECTORY DIRECTORY 2020 ESSENTIAL REFERENCE FOR THE STRING INDUSTRY 2020 In association with Roderich Paesold – Germany The Strad publishes essential market-leading supplements including a business Meisterwerkstätten für feine Streichinstrumente & Bögen seit 1848 STRING COURSES INTERNATIONAL COURSES FOR STRING PLAYERS AND MAKERS directory, guides to master classes and degree courses and an annual review of the latest accessories. We also publish a detailed instrument calendar, sponsored special WWW.THESTRAD.COM editions, and posters - all with promotional opportunities available. WWW.THESTRAD.COM 2020 EDITION £20.00 US$30.00 €25.00 Supplement to The Strad January 2020 DIGITAL PLATFORMS In 2019 we developed thestrad.com further by introducing The Strad Archive, allowing access to years of invaluable and exclusive content to our subscriber audience. -

Stradivarifestival

STRADIVARIfestival Cremona incanta. E suona Musical Enchantment in Cremona Cremona, Italy 14.09 - 12.10.2014 CONSIGLIO DI AMMINISTRAZIONE Fondazione Museo del Violino Antonio Stradivari Cremona - Soci Fondatori Gianluca Galimberti, Paolo Salvelli Paolo Bodini, Luigi Vinci, Roberto Zanchi CONSIGLIO GENERALE Gianluca Galimberti, Presidente Giovanni Arvedi, Presidente onorario Paolo Salvelli, Vicepresidente Paolo Bodini, Presidente “friends of Stradivari” Gian Domenico Auricchio, Stefano Bolis Chiara Bondioni, Manuela Bonetti Rossano Bonetti, Giuseppe Ghisani Renzo Rebecchi, Alessandro Tantardini Luigi Vinci, Roberto Zanchi Direttore Generale Museo del Violino Virginia Villa Direttore Artistico Stradivari Festival Francesca Colombo Tutto ciò che valorizza le eccellenze della nostra città vede The administration supports everything that promotes our city’s merits. l’Amministrazione presente come sostegno e come promozione. The council is working on extensive and detailed programming, based “ Come Giunta stiamo lavorando ad una programmazione ampia “ on alliances and shared projects. We’d like to thank the Museo del e precisa, fatta di alleanze e progetti condivisi. L’iniziativa Violino and Cavalier Giovanni Arvedi for making the STRADIVARIfestival STRADIVARIfestival, voluta dal Museo del Violino e dal Cavalier a reality. It’s an opportunity for the whole city. Giovanni Arvedi, che ringraziamo, è un’opportunità per tutta la città. Gianluca Galimberti Gianluca Galimberti Mayor of Cremona - President of Fondazione Museo del Violino Antonio Stradivari Sindaco di Cremona - Presidente Fondazione Museo del Violino Antonio Stradivari The STRADIVARIfestival is a privileged occasion, bringing together STRADIVARIfestival è un momento privilegiato dove, nel segno creativity and scientific rigour, product and gesture, symbolic content della liuteria, trovano sintesi creatività e rigore scientifico, prodotto “ and wonderfully physical objects, all under the banner of violin “ e gesto, contenuti simbolici e oggetti meravigliosamente fisici. -

Violin Detective

COMMENT BOOKS & ARTS instruments have gone up in value after I found that their soundboards matched trees known to have been used by Stradivari; one subsequently sold at auction for more than four times its estimate. Many convincing for- KAMILA RATCLIFF geries were made in the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, but the science did not exist then. Forgers now are aware of dendro- chronology, and it could be a problem if they use wood from old chalets to build sophisti- cated copies of historical instruments. How about unintentional deceit? I never like to ‘kill’ a violin — reveal it as not what it seems. But if the wood does not match the claims, I investigate. I was recently sent photos of a violin supposedly made by an Italian craftsman who died in 1735. The wood dated to the 1760s, so I knew he could not have made it. But I did see strong cor- relations to instruments made by his sons and nephews who worked in the 1770s. So Peter Ratcliff restores and investigates violins from his workshop in Hove, UK. I deduced that the violin might have been damaged and an entirely new soundboard made after the craftsman’s death. The violin Q&A Peter Ratcliff was pulled from auction, but not before it had received bids of more than US$100,000. Will dendrochronology change the market? Violin detective I think it already has, and has called into Peter Ratcliff uses dendrochronology — tree-ring dating — to pin down the age and suggest the question some incorrect historical assump- provenance of stringed instruments. -

Secretaries of Defense

Secretaries of Defense 1947 - 2021 Historical Office Office of the Secretary of Defense Contents Historical Origins of the Secretary of Defense . iii Secretaries of Defense . 1 Secretaries of Defense Demographics . 28 History of the Positional Colors for the Office of the Secretary of Defense . 29 “The Secretary of Defense’s primary role is to ensure the national security . [and] it is one of the more difficult jobs anywhere in the world. He has to be a mini-Secretary of State, a procurement expert, a congressional relations expert. He has to understand the budget process. And he should have some operational knowledge.” Frank C. Carlucci former Secretary of Defense Prepared by Dr. Shannon E. Mohan, Historian Dr. Erin R. Mahan, Chief Historian Secretaries of Defense i Historical Origins of the Secretary of Defense The 1947 National Security Act (P.L. 80-253) created the position of Secretary of Defense with authority to establish general policies and programs for the National Military Establishment. Under the law, the Secretary of Defense served as the principal assistant to the President in all matters relating to national security. James V. Forrestal is sworn in as the first Secretary of Defense, September 1947. (OSD Historical Office) The 1949 National Security Act Amendments (P.L. 81- 216) redefined the Secretary of Defense’s role as the President’s principal assistant in all matters relating to the Department of Defense and gave him full direction, authority, and control over the Department. Under the 1947 law and the 1949 Amendments, the Secretary was appointed from civilian life provided he had not been on active duty as a commissioned officer within ten years of his nomination.