A Performance Management Framework for State and Local Government: from Measurement and Reporting to Management and Improving

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Associate Superintendent / Chief Business Officer

Sequoia Union High School District Job Description Associate Superintendent / Chief Business Officer LEVEL: Senior Management SALARY RANGE: Competitive, Negotiable and Based On Experience JOB SUMMARY: Under direction of the Superintendent, provides district wide leadership and supervises, plans, organizes, develops, and directs the Business Services Division, including the following departments: Fiscal Services, Accounting, Budget, Purchasing, Technology, Transportation, Nutrition, Grounds, Maintenance, Custodial, Operations, Energy, Nutrition, Risk Management, Construction and Planning including Bond Management Oversight; supervise and train management level division staff, promote programs to students, staff and the general public, supervise and participate in the preparation, accounting and maintenance of all related financial records, statements, reports and cost studies; provides and maintains efficient and effective business services to all schools and departments in the District, and to do other related work as required. ESSENTIAL FUNCTIONS (include but not limited to) The Associate Superintendent / Chief Business Officer provides District-wide leadership and direction in the following areas: 1. Oversees all business and administrative services programs, including all areas of development, implementation, and evaluation. 2. Represents the District in communicating and collaborating with other school districts, public agencies and the general public as directed. 3. Assists the Superintendent in establishing long-range and strategic -

As of July 22, 2021 TUESDAY, JULY 27

As of July 22, 2021 TUESDAY, JULY 27 10:00-10:30am WELLNESS BREAK Yoga in the NACUBO Booth 11:00–11:15am Welcome Susan Whealler Johnston, President and CEO, NACUBO Megan Strand, Host and Producer CBO Speaks 11:15am–12:15pm Opening Session: The Hidden Brain Shankar Vedantam, NPR Social Science Correspondent and Host of Hidden Brain Robert Moore, Senior Vice President for Finance and Administration, Colorado College NPR science correspondent Shankar Vedantam offers unique insights into how our unconscious biases — what he calls the hidden brain — affect the decisions we make both personally and as groups and organizations. He bases these insights on data, not on psychological theories of the subconscious. Few speakers bring such a trove of breakthroughs in social science research to their audiences’ concerns. The Hidden Brain. Like a puppeteer behind a curtain, the hidden brain shapes our behavior, our choices, and the course of our relationships. But unconscious biases don’t just live in our individual brains; they also influence the success or failure of our organizations. In his presentations, as in his book The Hidden Brain: How Our Unconscious Minds Elect Presidents, Control Markets, Wage Wars, and Save Our Lives, Vedantam reveals these unconscious patterns and he lays out ways in which we can avoid the mistakes they often cause. CPE Category: Personal Development 12:15-1:30pm EXPO HALL 12:30-1:00pm WELLNESS BREAK Meditation in the NACUBO Booth 1:30-2:30pm CONCURRENT SESSIONS Community College Business Officers Roundtable Melissa Beardmore, vice president for learning resources management, Anne Arundel Community College Liz Clark, vice president, policy and research, NACUBO Randy Roberson, vice president, leadership development, NACUBO As higher education moves beyond the pandemic, what do the next few years hold for community colleges? Turn on your camera and connect with community college colleagues to discuss post-pandemic business and financial management issues. -

Press Release Climeco Promotes Derek Six to Chief Business Officer

Press Release FOR IMMEDIATE DISTRIBUTION CONTACT Nancy Marshall, Marketing Director 864-266-1210 or [email protected] ClimeCo Promotes Derek Six to Chief Business Officer August 8, 2018 (BOYERTOWN, PA) – ClimeCo is pleased to announce the promotion of Derek Six as our new Chief Business Officer. ClimeCo has grown exponentially in the last three years by adding professionals with incredible talent and by expanding into new markets. Mr. Six’s new role as Chief Business Officer will combine the traditional roles of Chief Operating Officer and Chief Financial Officer. “Derek has demonstrated incredible leadership in these areas historically,” says Bill Flederbach, President & CEO of ClimeCo. “He is someone who has the skills, focus, and drive to elevate ClimeCo’s growth for the future.” Mr. Six joined ClimeCo in 2015 after serving as the CEO of Environmental Credit Corp and has worked in the environmental markets since 2006. He is deeply involved in Cap and Trade policy and Offset policy — including co-founding the Carbon Offset Provider’s Coalition (COPC) and participating in the Compliance Offset Developer’s Association (CODA), the Verified Emission Reduction Association (VERA), the Climate Action Reserve ODS workgroup, and many other policy and trade associations. “I am honored to be ClimeCo’s new Chief Business Officer as we position ourselves for some amazing growth,” says Derek Six. “We have seen some truly monumental shifts in the last couple of years and I am excited about our future.” ClimeCo is a leader in the management and development of environmental commodities. We combine unrivaled commodity market expertise with engineering and environmental assessment, permitting and transaction structuring to help clients maximize their environmental assets and minimize their regulatory costs. -

Report of the Board of Directors on the Proposed Resolutions Submitted 4 to the Combined Shareholders’ Meeting of 30 May 2018

REPORT OF THE BOARD OF DIRECTORS ON THE PROPOSED RESOLUTIONS SUBMITTED 4 TO THE COMBINED SHAREHOLDERS’ MEETING OF 30 MAY 2018 REPORT OF THE BOARD OF DIRECTORS ON THE PROPOSED RESOLUTIONS SUBMITTED TO THE COMBINED SHAREHOLDERS’ MEETING OF 30 MAY 2018 The Board of Directors convenes the Shareholders of the Allocation: Company to the Combined Shareholders’ Meeting to be • No allocation to the legal reserve – held on 30 May 2018, in order to report on the Company’s (the amount being beyond 10% of the share capital) operations during the financial year closed 31 December • Dividends €83,782,308.00 2017 and submit the following proposed resolutions to their approval: • Retained earnings €57,715,274.70 The ex-dividend date for the total gross dividend of €1.00 due Q A p p r ova l o f t h e 2 0 17 a n n u a l fi n a n c i a l s t a t e m e n t s for each share would be 4 June 2018 and its payment date st rd and allocation of results (1 to 3 ordinary 6 June 2018. resolutions) In the event of a change in the number of shares carrying a The first items on the agenda relate to the approval of right to a dividend in comparison with the 83,782,308 shares the annual financial statements (first resolution) and the comprising the share capital on 14 February 2018, the overall consolidated financial statements (second resolution). amount of dividends would be accordingly adjusted and Ipsen SA’s annual financial statements for the year closed the amount allocated to the retained earnings would be 31 December 2017 show a loss of €17,369,249.12. -

Document Title

Approval Date Name Job Title JOB DESCRIPTION Job Title: Chief Business Officer (CBO) Dept. Executive Reports to: Chief Executive Officer (CEO) Date: August 2017 Job Purpose: A key role within the Charity Executive Team, the Chief Business Officer reports to the CEO and directly assists on all operational, strategic, development, planning and governance matters including risk management This accountability is split with c 60% of the role allocated to the charity and c 40% of the remit allocated to DfE funded client organisations. • The CBO also takes full and direct responsibility for financial reporting, accounting, internal controls and audit. • The CBO also leads the Operations Team and assumes full responsibility for all financial, IT, HR, Estates/facilities management, health & safety and fundraising activities. Dimensions: (i.e. significant numerical quantities on which the job has either a direct or indirect impact) The position is a strategic executive business management and finance role as a member of the Executive Team and Management Group. The post supports the CEO to deliver a strong, strategic and sustainable financial future for the charity and DfE funded client organisations. The following posts report directly to the CBO: • Head of Human Resources & OD • Head of Governance, Information & Technology • Senior Fundraising Officer • Management Accountant, Accountant and Accounts Assistant Key Accountabilities: (Specify main accountabilities. Focus on results expected, in line with Job Purpose) Strategy and Planning • Provide leadership in developing strategic business plans. • Provide recommendations to enhance the charities and client projects' financial performance. • Advise on the financial implications of all business activities. • Ensure credibility of Full Trustee Board plus the Audit & Finance sub-committee through timely & accurate analysis of results vs. -

Press Release

Press Release Astellas Announces Management Structure TOKYO, February 4, 2021 - Astellas Pharma Inc. (TSE: 4503, President and CEO: Kenji Yasukawa, Ph.D., “Astellas” ) today announced the following Executive Comittee Standing Members effective from April 1, 2021. Executive Committee*1 Standing Members (as of April 2021) Under Corporate Strategic Plan 2018, Astellas highlights “Evolving How We Create VALUE with Focus Area Approach” as one of its strategic goals. The goal of the Focus Area approach is to create innovative pharmaceuticals for diseases with high unmet medical needs by identifying unique combinations of biologies with clear disease relevance and versatile modalities / technologies. Chief Scientific Officer (CScO) is newly assigned for accelerating the Focus Area approach by strengthening research activities. Yoshitsugu Shitaka, who is currently the President of Astellas Institute for Regenerative Medicine and has contributed significantly to the development of the cell therapy, will be appointed to CScO, and will also serve as the President, Drug Discovery Research. Furthermore, Chief Business Officer (CBO) is newly assigned to lead and supervise the execution of Corporate Strategic Plan starting in Fiscal Year 2021. Percival Barretto-Ko, who has demonstrated a strong track record of robust leadership as President of United States Commercial will be appointed to CBO. Title Name New Representative Director, Kenji Yasukawa President and Chief Excecutive Officer (CEO) Representative Director, Naoki Okamura Corporate Executive Vice President, Chief Strategy Officer (CStO) and Chief Financial Officer (CFO) Chief Administrative Officer (CAO) and Fumiaki Sakurai Chief Ethics & Compliance Officer (CECO) Chief Medical Officer (CMO) Bernhardt Zeiher Chief Commercial Officer (CCO) Yukio Matsui Chief Scientific Officer (CScO) Yoshitsugu Shitaka ✔ Chief Business Officer (CBO) Percival Barretto-Ko ✔ General Counsel Catherine Levitt 1 *1 Executive Committee: an organization that discusses significant matters of management across Astellas. -

Geron Corporation 919 E

GERON CORPORATION 919 E. Hillsdale Blvd., Suite 250 Foster City, CA 94404 March 22, 2021 Dear Fellow Geron Stockholder: You are cordially invited to attend the 2021 Annual Meeting of Stockholders (the “Annual Meeting”) of Geron Corporation to be held on Tuesday, May 11, 2021, at 8:00 a.m., Pacific Daylight Time. In light of the COVID-19 pandemic, for the safety of all our stockholders and personnel, and taking into account federal, state and local guidance, we have determined that the Annual Meeting will be held in a virtual meeting format only, via the Internet, with no physical in-person meeting. You will be able to attend and participate in the virtual Annual Meeting online by visiting www.virtualshareholdermeeting.com/GERN2021, where you will be able to listen to the meeting live, submit questions, and vote. You will not be able to attend the meeting in person. Instructions on how to participate in the virtual Annual Meeting and demonstrate proof of stock ownership are posted at www.virtualshareholdermeeting.com/GERN2021. The webcast of the virtual Annual Meeting will be archived for one year after the date of the virtual Annual Meeting at www.virtualshareholdermeeting.com/GERN2021. As permitted by the rules of the Securities and Exchange Commission, we are pleased to furnish our proxy materials to stockholders primarily over the Internet. Consequently, most stockholders will receive a notice with instructions for accessing proxy materials and voting via the Internet, instead of paper copies of proxy materials. However, this notice will provide information on how stockholders may obtain paper copies of proxy materials if they choose. -

2021 Notice of Meeting

INDIVIOR PLC NOTICE OF ANNUAL GENERAL MEETING THURSDAY, MAY 6, 2021 AT 3.00PM AT THE OFFICES OF INDIVIOR PLC, 234 BATH ROAD, SLOUGH, BERKSHIRE SL1 4EE THIS DOCUMENT IS IMPORTANT AND REQUIRES YOUR IMMEDIATE ATTENTION. If you are in any doubt about the action to be taken, you should immediately consult your stockbroker, solicitor, accountant or other independent advisor who, if you are taking advice in the United Kingdom, is duly authorized under the Financial Services and Markets Act 2000, or an appropriately authorized independent advisor if you are in a territory outside the United Kingdom. If you have recently sold or transferred all of your shares in Indivior PLC, please forward this document, together with the accompanying documents (but not the personalized form of proxy), as soon as possible either to the purchaser or transferee or to the person who arranged the sale or transfer so they can pass these documents to the person who now holds the shares. If you have sold or otherwise transferred only part of your holding, you should retain this document and its enclosures. Indivior PLC, 234 Bath Road, Slough, Berkshire, SL1 4EE Registered in England & Wales. Company number 09237894 N O T I C E O F A N N U A L G E N E R A L M E E T I N G DEAR SHAREHOLDER, AGM format in light of the coronavirus pandemic I AM PLEASED TO ENCLOSE THE NOTICE OF The Board has been closely monitoring the coronavirus MEETING FOR THE ANNUAL GENERAL MEETING (COVID-19) pandemic and our priority continues to be the (‘AGM’) OF THE COMPANY. -

Deputy Superintendent, Chief Business Officer

JOB DESCRIPTION San Diego County Office of Education Deputy Superintendent, Chief Business Officer Purpose Statement The Deputy Superintendent, Chief Business Officer serves as the San Diego County Office of Education’s (“SDCOE”) chief business official and acts for, represents, and exercises the authority of the County Superintendent of Schools (“Superintendent”) as assigned. Hierarchically, the Deputy Superintendent, Chief Business Officer is the second-in-command of all SDCOE functions after the Superintendent. Essential Functions • Collaborates with the Superintendent and the Chief of Staff on operational and policy issues and oversees all fiscal matters for SDCOE, and serves as the executive in charge in the Superintendent’s absence. • Co-leads the Superintendent’s Strategic Leadership Team in the overall planning and direction of County Office functions and services; advises the Superintendent regarding use of resources, priorities, program opportunities, and methods to enhance the delivery of programs and support services. • Plans, directs, and supervises the Business Services Division, including District Financial Services, Internal Business, Facilities Planning, Maintenance and Operations, and Risk Management; confers with staff on individual school district finance problems, business applications, program planning, and other matters. o District Financial Services includes Business Advisory Services, Legal Advisory Services, Pupil Accounting, Commercial Warrants, Payroll Services, and Retirement Reporting o Internal Business -

Summary of Proceedings: Export Development Canada's Advisory

Summary of Proceedings: Export Development Canada’s Advisory Council on Corporate Sustainability and Responsibility Date: May 20, 2021 Participant Guest Speaker: Jonathan Hackett, Managing Director and Head, Sustainable Finance Group, Bank of Montreal CSR Advisory Council Members: Martine Irman, EDC Board Member, Senior Vice-President at TD Bank Group, Vice Chair at TD Securities Gordon Lambert, Suncor Sustainability Executive in Residence, Ivey School of Business, Western University Rosemary McCarney, Former Canadian Ambassador and Permanent Representative to the United Nations in Geneva Marie-Lucie Morin, Corporate Director and member of the Security and Intelligence Review committee Anita Ramasastry, Henry M. Jackson Professor of Law and Director of the Sustainable International Development Graduate Program at the University of Washington School of Law Christa Wessel, Chief Operating Officer and General Counsel at ClearView Strategic Partners Inc. David Wheeler, Co-Founder of the Academy for Sustainable Innovation Absent: Eduardo Bohorquez, Executive Director of Transparencia Mexicana From Export Development Canada (EDC): Mairead Lavery, President and Chief Executive Officer, and Council Chair Carl Burlock, Executive Vice-President and Chief Business Officer Justine Hendricks, Chief Corporate Sustainability Officer Todd Winterhalt, Senior Vice-President of Communications and Corporate Strategy Sophie Roy, Vice-President, Corporate Sustainability and Responsibility Chris Pullen, Director of Environmental, Social and Governance Strategy Implementation SESSION OVERVIEW The objective of the spring session of the Advisory Council on Corporate Sustainability and Responsibility was to equip the President and Executive Team with insights and advice on EDC’s approach to developing a sustainable finance framework. The Council heard from guest speaker Jonathan Hackett, Managing Director and Head of the Sustainable Finance Group at the Bank of Montreal, who provided an overview of sustainable finance and the impact on access to capital. -

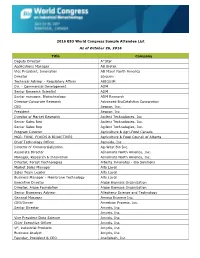

2016 BIO World Congress Sample Attendee List As of October 26

2016 BIO World Congress Sample Attendee List As of October 26, 2016 Title Company Deputy Director A*Star Applications Manager AB Biotek Vice President, Innovation AB Mauri North America Director abiquim Technical Advisor - Regulatory Affairs ABIQUIM Dir. - Commercial Development ADM Senior Research Scientist ADM Senior manager, Biotechnology ADM Research Director-Corporate Research Advanced BioCatalytics Corporation CEO Aequor, Inc. President Aequor, Inc. Director of Market Research Agilent Technologies, Inc Senior Sales Rep Agilent Technologies, Inc. Senior Sales Rep Agilent Technologies, Inc. Program Director Agriculture & Agri-Food Canada MGR. FUNC. FOODS & BIOACTIVES Agriculture & Food Council of Alberta Chief Technology Officer Agrivida, Inc Director of Commercialization Ag-West Bio Inc. Associate Director Ajinomoto North America, Inc. Manager, Research & Innovation Ajinomoto North America, Inc. Director, Forest Technologies Alberta Innovates - Bio Solutions Market Sales Manager Alfa Laval Sales Team Leader Alfa Laval Business Manager - Membrane Technology Alfa Laval Executive Director Algae Biomass Organization Director, Algae Foundation Algae Biomass Organization Senior Bioenergy Advisor Allegheny Science and Technology General Manager Amano Enzyme Inc. CEO/Owner American Process, Inc. Senior Director Amyris, Inc. Amyris, Inc. Vice President Data Science Amyris, Inc. Chief Executive Officer Amyris, Inc. VP, Industrial Products Amyris, Inc. Business Analyst Amyris, Inc. Founder, President & CEO Anellotech, Inc. Title Company VP Business Develpment Anellotech, Inc. Exec President Arancia Industrial CEO Arbiom VP Operations Arbiom Business Development Manager ARD Project Manager B.R.I Biorefinery Research & Innovations ARD Head of Fractionation and Biotechnology Departments ARD CEO Ardra Portfolio Manager Arizona State University Associate Research Professor Arizona State University ARPA-E Fellow ARPA-E Chief Executive Officer Arzeda CBO Arzeda Manager Asahi Kasei America Dr. -

AGM Proxy Statement 2019

Exhibit 99.1 August 13, 2019 Dear Shareholder, You are cordially invited to attend the 2019 Annual General Meeting of Shareholders (the “Meeting”) of AudioCodes Ltd. (the “Company” or “AudioCodes”), to be held on September 10, 2019, at 2:00 p.m., local time, or at any adjournment or postponement thereof, for the purposes set forth herein and in the accompanying Notice. The Meeting will be held at the offices of the Company located at 1 Hayarden Street, Airport City, Lod 7019900, Israel. The telephone number at that address is +972-3-976-4000. At the Meeting, shareholders will be asked to consider and vote on the matters listed in the enclosed Notice of Annual General Meeting of Shareholders. AudioCodes’ Board of Directors recommends that you vote FOR all of the proposals listed in the Notice. Management will also report on the affairs of AudioCodes, and a discussion period will be provided for questions and comments of general interest to shareholders. Whether or not you plan to attend the Meeting, it is important that your ordinary shares be represented and voted at the Meeting. Accordingly, after reading the enclosed Notice of Annual General Meeting of Shareholders and the accompanying Proxy Statement, please sign, date and mail the enclosed proxy card in the envelope provided. If a shareholder’s shares are held through a member of the Tel-Aviv Stock Exchange (the “TASE”) for trading thereon, such shareholder may vote in person or via proxy at the meeting or by delivering or mailing (via registered mail) his, her or its completed Hebrew written ballot (in the form filed by the Company via the MAGNA online platform (“MAGNA”) of the Israel Securities Authority (“ISA”)) to the offices of the Company at the address set forth above, Attention: Chief Legal Officer.