Robb Leigh Davis for the LOVE of CLIFF & CLAIR

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

FY14 Tappin' Study Guide

Student Matinee Series Maurice Hines is Tappin’ Thru Life Study Guide Created by Miller Grove High School Drama Class of Joyce Scott As part of the Alliance Theatre Institute for Educators and Teaching Artists’ Dramaturgy by Students Under the guidance of Teaching Artist Barry Stewart Mann Maurice Hines is Tappin’ Thru Life was produced at the Arena Theatre in Washington, DC, from Nov. 15 to Dec. 29, 2013 The Alliance Theatre Production runs from April 2 to May 4, 2014 The production will travel to Beverly Hills, California from May 9-24, 2014, and to the Cleveland Playhouse from May 30 to June 29, 2014. Reviews Keith Loria, on theatermania.com, called the show “a tender glimpse into the Hineses’ rise to fame and a touching tribute to a brother.” Benjamin Tomchik wrote in Broadway World, that the show “seems determined not only to love the audience, but to entertain them, and it succeeds at doing just that! While Tappin' Thru Life does have some flaws, it's hard to find anyone who isn't won over by Hines showmanship, humor, timing and above all else, talent.” In The Washington Post, Nelson Pressley wrote, “’Tappin’ is basically a breezy, personable concert. The show doesn’t flinch from hard-core nostalgia; the heart-on-his-sleeve Hines is too sentimental for that. It’s frankly schmaltzy, and it’s barely written — it zips through selected moments of Hines’s life, creating a mood more than telling a story. it’s a pleasure to be in the company of a shameless, ebullient vaudeville heart.” Maurice Hines Is . -

Feminism, Postfeminism, Liz Lemonism: Comedy and Gender Politics on 30 Rock

Genders 1998-2013 Genders 1998-2013 Genders 1998-2013 Home (/gendersarchive1998-2013/) Feminism, Postfeminism, Liz Lemonism: Comedy and Gender Politics on 30 Rock Feminism, Postfeminism, Liz Lemonism: Comedy and Gender Politics on 30 Rock May 1, 2012 • By Linda Mizejewski (/gendersarchive1998-2013/linda-mizejewski) [1] The title of Tina Fey's humorous 2011 memoir, Bossypants, suggests how closely Fey is identified with her Emmy-award winning NBC sitcom 30 Rock (2006-), where she is the "boss"—the show's creator, star, head writer, and executive producer. Fey's reputation as a feminist—indeed, as Hollywood's Token Feminist, as some journalists have wryly pointed out—heavily inflects the character she plays, the "bossy" Liz Lemon, whose idealistic feminism is a mainstay of her characterization and of the show's comedy. Fey's comedy has always focused on gender, beginning with her work on Saturday Night Live (SNL) where she became that show's first female head writer in 1999. A year later she moved from behind the scenes to appear in the "Weekend Update" sketches, attracting national attention as a gifted comic with a penchant for zeroing in on women's issues. Fey's connection to feminist politics escalated when she returned to SNL for guest appearances during the presidential campaign of 2008, first in a sketch protesting the sexist media treatment of Hillary Clinton, and more forcefully, in her stunning imitations of vice-presidential candidate Sarah Palin, which launched Fey into national politics and prominence. [2] On 30 Rock, Liz Lemon is the head writer of an NBC comedy much likeSNL, and she is identified as a "third wave feminist" on the pilot episode. -

Mary, Roseanne, and Carrie: Television and Fictional Feminism by Rachael Horowitz Television, As a Cultural Expression, Is Uniqu

Mary, Roseanne, and Carrie: Television and Fictional Feminism By Rachael Horowitz Television, as a cultural expression, is unique in that it enjoys relatively few boundaries in terms of who receives its messages. Few other art forms share television's ability to cross racial, class and cultural divisions. As an expression of social interactions and social change, social norms and social deviations, television's widespread impact on the true “general public” is unparalleled. For these reasons, the cultural power of television is undeniable. It stands as one of the few unifying experiences for Americans. John Fiske's Media Matters discusses the role of race and gender in US politics, and more specifically, how these issues are informed by the media. He writes, “Television often acts like a relay station: it rarely originates topics of public interest (though it may repress them); rather, what it does is give them high visibility, energize them, and direct or redirect their general orientation before relaying them out again into public circulation.” 1 This process occurred with the topic of feminism, and is exemplified by the most iconic females of recent television history. TV women inevitably represent a strain of diluted feminism. As with any serious subject matter packaged for mass consumption, certain shortcuts emerge that diminish and simplify the original message. In turn, what viewers do see is that much more significant. What the TV writers choose to show people undoubtedly has a significant impact on the understanding of American female identity. In Where the Girls Are , Susan Douglas emphasizes the effect popular culture has on American girls. -

An Analysis of Hegemonic Social Structures in "Friends"

"I'LL BE THERE FOR YOU" IF YOU ARE JUST LIKE ME: AN ANALYSIS OF HEGEMONIC SOCIAL STRUCTURES IN "FRIENDS" Lisa Marie Marshall A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate College of Bowling Green State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY August 2007 Committee: Katherine A. Bradshaw, Advisor Audrey E. Ellenwood Graduate Faculty Representative James C. Foust Lynda Dee Dixon © 2007 Lisa Marshall All Rights Reserved iii ABSTRACT Katherine A. Bradshaw, Advisor The purpose of this dissertation is to analyze the dominant ideologies and hegemonic social constructs the television series Friends communicates in regard to friendship practices, gender roles, racial representations, and social class in order to suggest relationships between the series and social patterns in the broader culture. This dissertation describes the importance of studying television content and its relationship to media culture and social influence. The analysis included a quantitative content analysis of friendship maintenance, and a qualitative textual analysis of alternative families, gender, race, and class representations. The analysis found the characters displayed actions of selectivity, only accepting a small group of friends in their social circle based on friendship, gender, race, and social class distinctions as the six characters formed a culture that no one else was allowed to enter. iv ACKNOWLEDGMENTS This project stems from countless years of watching and appreciating television. When I was in college, a good friend told me about a series that featured six young people who discussed their lives over countless cups of coffee. Even though the series was in its seventh year at the time, I did not start to watch the show until that season. -

Summer Classic Film Series, Now in Its 43Rd Year

Austin has changed a lot over the past decade, but one tradition you can always count on is the Paramount Summer Classic Film Series, now in its 43rd year. We are presenting more than 110 films this summer, so look forward to more well-preserved film prints and dazzling digital restorations, romance and laughs and thrills and more. Escape the unbearable heat (another Austin tradition that isn’t going anywhere) and join us for a three-month-long celebration of the movies! Films screening at SUMMER CLASSIC FILM SERIES the Paramount will be marked with a , while films screening at Stateside will be marked with an . Presented by: A Weekend to Remember – Thurs, May 24 – Sun, May 27 We’re DEFINITELY Not in Kansas Anymore – Sun, June 3 We get the summer started with a weekend of characters and performers you’ll never forget These characters are stepping very far outside their comfort zones OPENING NIGHT FILM! Peter Sellers turns in not one but three incomparably Back to the Future 50TH ANNIVERSARY! hilarious performances, and director Stanley Kubrick Casablanca delivers pitch-dark comedy in this riotous satire of (1985, 116min/color, 35mm) Michael J. Fox, Planet of the Apes (1942, 102min/b&w, 35mm) Humphrey Bogart, Cold War paranoia that suggests we shouldn’t be as Christopher Lloyd, Lea Thompson, and Crispin (1968, 112min/color, 35mm) Charlton Heston, Ingrid Bergman, Paul Henreid, Claude Rains, Conrad worried about the bomb as we are about the inept Glover . Directed by Robert Zemeckis . Time travel- Roddy McDowell, and Kim Hunter. Directed by Veidt, Sydney Greenstreet, and Peter Lorre. -

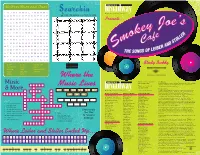

Study Buddy CASSETTE DION ELVIS GUITAR IPOD PHONOGRAPH RADIO RECORD RHYTHM ROCK ROLL Where The

Rhythm, Blues and Clues I V J X F Y R D L Y W D U N H Searchin Michael Presser, Executive Director A Q X R O C K F V K K P D O P Help the musical note find it’s home B L U E S B Y X X F S F G I A Presents… Y C L C N T K F L V V E A D R Y A K O A Z T V E I O D O A G E S W R R T H K J P U P T R O U S I D H S O N W G I I U G N Z E G V A Y V F F F U E N G O P T V N L O T S C G X U Q E H L T G H B E R H O J H D N L P N E C S U W Q B M D W S G Y M Z O B P M R O Y F D G S R W K O F D A X E J X L B M O W Z K B P I D R V X T C B Y W P K P F Y K R Q R E Q F V L T L S G ALBUM BLUES BROADWAY Study Buddy CASSETTE DION ELVIS GUITAR IPOD PHONOGRAPH RADIO RECORD RHYTHM ROCK ROLL Where the 630 Ninth Avenue, Suite 802 Our Mission: Music Inside Broadway is a professional New York City based children’s theatre New York, NY 10036 12 company committed to producing Broadway’s classic musicals in a Music Lives Telephone: 212-245-0710 contemporary light for young audiences. -

Fantasticks 2 Playbill

JUNE 7 - JULY 1 Sales Exchange Co., Inc. Jewelers and Collateral Loanbrokers Classic and Contemporary Platinum and Gold Jewelry designs that will excite your senses. One East Main St., Patchogue 631.289.9899 www.wmjoneills.com Mention this ad for 10% discount on purchase 2 The Pine Grove Inn has served generations of guests since its establishment in 1910. Our seasonal menus emphasize prime beef, fresh local seafood and the traditional German fare which made us famous. The Palm Bar & outdoor patio overlooks the Swan River. $6 Martinis Enjoy Live Music Thursday through Saturday Tuesday through Friday Open for Lunch and Dinner Wednesday through Sunday from 4-7 at the bar Available for Parties Monday & Tuesday Choose us for your next special event – our catering department will be pleased to work with you to design your affair Wednesday Lobsterfest Thursday Prime Rib Night Chapel Avenue & First St., Patchogue, NY 11772 • 631.475.9843 www.pinegroveinn.com PRESENT THIS VOUCHER FOR PRESENT THIS VOUCHER FOR $5 OFF LUNCH $10 OFF DINNER on checks of $30 or more on checks of $60 or more Expires July 7, 2006. Reservations suggested. Expires July 7, 2006. Reservations suggested. May not be combined with any other promotional offer. May not be combined with any other promotional offer. Specialists in Family Owned & Quality & Service Operated Since 1976 1135 Montauk Hwy., Mastic • 399-1890/653-RUGS 721 Rte. 25A (next to Personal Fitness), Rocky Point • 631-744-1810 Open 7 Days We love it when you love what you’re walking on. 4 European-style Desserts and Espresso Drinks Open Late 6 Nights per Week Signature Martini Bar Outdoor Café Seating Live Jazz Every Thursday & Restaurant Late Night Friday Zagat Rated Excellent 2001-2006 14 Station Road, Bellport Village 286-3300 GATEWAY PLAYHOUSE 2006 5 E HARBOR SID TH “Incomparable Seafood Restaurant” E Highly Recommended: Open 7 Days a Week * * * at 11:30 a.m. -

SUNRISE NEWS and VIEWS Martha’S Musings

Volume 39 Issue 8 August 2019 SUNRISE PRESBYTERIAN CHURCH SUNRISE NEWS AND VIEWS Martha’s Musings In June, Tom Reid, who often fills our pulpit when I am away, preached a sermon: “Upon Reading Your Newsletter.” In the sermon, he lifted up the life and ministry at Sunrise he discovers as he reads our monthly newsletter. Our newsletter is full of mission we have done – or mission we are planning to do. In the newsletter we highlight fellowship activities and the life of our congregation. It’s full of life. That life spills out of these pages and offers opportunities and possibilities to all of us and to everyone who reads the newsletter. It’s possible that we may fail to realize just how important what we do as Sunrise Presbyterian Church really is. Just this summer Sunrise hosted Heartland Traveling Day Camp. During camp week, 56 kids from kindergarten through 6th grade attended full day camp sessions. They played in water, they read the Bible, they rode horses, they sang – in short they had what many called, “The best week in my year!” That’s mission. It’s mission when a counselor asks if Sunrise had an extra Bible to give to a child who wanted one. It’s mission when our children grow emotionally during the week. It’s mission that costs us dollars to offer – but the results are so worth the cost. This summer we also hosted CASTLE for their 15th year! With 99 children enrolled, the kids had fun with STEM activities, recreation, reading help, field trips and lots of games. -

For Immediate Release

‘ICE DREAMS’ CAST BIOS SHELLEY LONG (Harriet Clayton) – Shelley Long is an Emmy® and Golden Globe-winning actress. She began her career after attending Northwestern University by performing in small films and local theater, eventually becoming co-host and associate producer of a critically acclaimed Chicago magazine show “Sorting it Out,” for which she won three local Emmys. She eventually returned to her first passion, acting, and joined Chicago’s famed Second City improvisational comedy troupe. Shortly after, Long landed a role as barmaid Diane Chambers in the long-running NBC comedy “Cheers.” Long entertained audiences for five seasons, garnering an Emmy and two Golden Globes. She returned for the series’ top-rated finale and has reprised her “Cheers” role in guest appearances on NBC’s “Frasier,” one episode garnering an Emmy nomination. Long recently starred in a film short titled “A Couple of White Chicks at the Hairdresser,” and starred in a children’s DVD, “Mr. Vinegar and the Curse.” In 2006, Long starred in “Honeymoon With Mom” on Lifetime, and co-starred in the Hallmark Channel Valentine’s Day movie, “Falling In Love with the Girl Next Door.” She has made a number of guest TV appearances including “Boston Legal,” “Yes, Dear, “Joan of Arcadia,” “Complete Savages” and, most recently, ABC’s hit comedy “Modern Family.” Long was seen in the Robert Altman film “Dr. T and the Women” for Artisan Entertainment. Written by Anne Rapp and executive produced by Cindy Cowan and James McLindon, the film tells the story of a gynecologist, played by Richard Gere, who is battling a mid-life crisis. -

Makers: Women in Hollywood

WOMEN IN HOLLYWOOD OVERVIEW: MAKERS: Women In Hollywood showcases the women of showbiz, from the earliest pioneers to present-day power players, as they influence the creation of one of the country’s biggest commodities: entertainment. In the silent movie era of Hollywood, women wrote, directed and produced, plus there were over twenty independent film companies run by women. That changed when Hollywood became a profitable industry. The absence of women behind the camera affected the women who appeared in front of the lens. Because men controlled the content, they created female characters based on classic archetypes: the good girl and the fallen woman, the virgin and the whore. The women’s movement helped loosen some barriers in Hollywood. A few women, like 20th century Fox President Sherry Lansing, were able to rise to the top. Especially in television, where the financial stakes were lower and advertisers eager to court female viewers, strong female characters began to emerge. Premium cable channels like HBO and Showtime allowed edgy shows like Sex in the City and Girls , which dealt frankly with sex from a woman’s perspective, to thrive. One way women were able to gain clout was to use their stardom to become producers, like Jane Fonda, who had a breakout hit when she produced 9 to 5 . But despite the fact that 9 to 5 was a smash hit that appealed to broad audiences, it was still viewed as a “chick flick”. In Hollywood, movies like Bridesmaids and The Hunger Games , with strong female characters at their center and strong women behind the scenes, have indisputably proven that women centered content can be big at the box office. -

Here Are a Number of Recognizable Singers Who Are Noted As Prominent Contributors to the Songbook Genre

Music Take- Home Packet Inside About the Songbook Song Facts & Lyrics Music & Movement Additional Viewing YouTube playlist https://bit.ly/AllegraSongbookSongs This packet was created by Board-Certified Music Therapist, Allegra Hein (MT-BC) who consults with the Perfect Harmony program. About the Songbook The “Great American Songbook” is the canon of the most important and influential American popular songs and jazz standards from the early 20th century that have stood the test of time in their life and legacy. Often referred to as "American Standards", the songs published during the Golden Age of this genre include those popular and enduring tunes from the 1920s to the 1950s that were created for Broadway theatre, musical theatre, and Hollywood musical film. The times in which much of this music was written were tumultuous ones for a rapidly growing and changing America. The music of the Great American Songbook offered hope of better days during the Great Depression, built morale during two world wars, helped build social bridges within our culture, and whistled beside us during unprecedented economic growth. About the Songbook We defended our country, raised families, and built a nation while singing these songs. There are a number of recognizable singers who are noted as prominent contributors to the Songbook genre. Ella Fitzgerald, Fred Astaire, Rosemary Clooney, Nat King Cole, Sammy Davis Jr., Judy Garland, Billie Holiday, Lena Horne, Al Jolson, Dean Martin, Frank Sinatra, Mel Tormé, Margaret Whiting, and Andy Williams are widely recognized for their performances and recordings which defined the genre. This is by no means an exhaustive list; there are countless others who are widely recognized for their performances of music from the Great American Songbook. -

Linda Twine, a Native of Muskogee, OK, Graduated from Oklahoma City University in 1966, with a Bachelor of Arts Degree in Music

Linda Twine, a native of Muskogee, OK, graduated from Oklahoma City University in 1966, with a bachelor of arts degree in music. There, she studied piano with the esteemed Dr. Clarence Burg and Professor Nancy Apgar. After graduating from OCU, Twine studied at the Manhattan School of Music in New York, where she earned a master’s degree, and made New York her home. She began her musical career in New York, teaching music in public school by day and accompanying classical and jazz artists at night. At one of these engagements, she was asked if she would like to substitute for the keyboardist of the Tony Award winning Broadway hit, “The Wiz.” Her positive response began a long career in Broadway musicals from keyboard substitute to assistant conductor of Broadway orchestras. In 1981, Twine transitioned to conductor when Lena Horne asked her to conduct her one-woman hit, “Lena Horne: The Lady and Her Music.” This garnered Twine the respect of her peers and as a much sought-after Broadway musical conductor. In addition to “The Wiz” and “Lena Horne,” Twine’s Broadway credits include, “Ain’t Misbehavin’,” “Big River” (the score composed by Oklahoman Roger Miller), “Jelly’s Last Jam,” “Frog and Toad,” “Caroline or Change,” “Purlie,” and the current “The Color Purple,” starring Fantasia. Not only a distinguished conductor, Twine is also a composer and arranger. She composed “Changed My Name,” a cantata inspired by slave women Sojourner Truth and Harriet Tubman, and written for two actresses, four soloists, and a chorus. Her popular spiritual arrangements are published by Hinshaw.