UC Riverside UCR Honors Capstones 2018-2019

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Identity and Representation on the Neoliberal Platform of Youtube

Identity and Representation on the Neoliberal Platform of YouTube Andra Teodora Pacuraru Student Number: 11693436 30/08/2018 Supervisor: Alberto Cossu Second Reader: Bernhard Rieder MA New Media and Digital Culture University of Amsterdam Table of Contents Introduction ............................................................................................................................................ 2 Chapter 1: Theoretical Framework ........................................................................................................ 4 Neoliberalism & Personal Branding ............................................................................................ 4 Mass Self-Communication & Identity ......................................................................................... 8 YouTube & Micro-Celebrities .................................................................................................... 10 Chapter 2: Case Studies ........................................................................................................................ 21 Methodology ............................................................................................................................. 21 Who They Are ........................................................................................................................... 21 Video Evolution ......................................................................................................................... 22 Audience Statistics ................................................................................................................... -

Developing a Curriculum for TEFL 107: American Childhood Classics

Minnesota State University Moorhead RED: a Repository of Digital Collections Dissertations, Theses, and Projects Graduate Studies Winter 12-19-2019 Developing a Curriculum for TEFL 107: American Childhood Classics Kendra Hansen [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://red.mnstate.edu/thesis Part of the American Studies Commons, Education Commons, and the English Language and Literature Commons Recommended Citation Hansen, Kendra, "Developing a Curriculum for TEFL 107: American Childhood Classics" (2019). Dissertations, Theses, and Projects. 239. https://red.mnstate.edu/thesis/239 This Project (696 or 796 registration) is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate Studies at RED: a Repository of Digital Collections. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations, Theses, and Projects by an authorized administrator of RED: a Repository of Digital Collections. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Developing a Curriculum for TEFL 107: American Childhood Classics A Plan B Project Proposal Presented to The Graduate Faculty of Minnesota State University Moorhead By Kendra Rose Hansen In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts in Teaching English as a Second Language December, 2019 Moorhead, Minnesota Copyright 2019 Kendra Rose Hansen v Dedication I would like to dedicate this thesis to my family. To my husband, Brian Hansen, for supporting me and encouraging me to keep going and for taking on a greater weight of the parental duties throughout my journey. To my children, Aidan, Alexa, and Ainsley, for understanding when Mom needed to be away at class or needed quiet time to work at home. -

Magazine for Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual , Trans and Questioning Young People

g - Zine Magazine for Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual , Trans and Questioning young people. Celebrating Providing 40 years of support for LGBTQ+ Young People in Liverpool! Produced by the young people of GYRO & T.A.Y 1 About The g-Zine In this Issue G-Zine has been created and produced by young people from GYRO and The Action Youth. It’s by LGBTQ+ young people for LGBTQ+ What is the G - Zine.............................................................. Page 3 young people, it’s full of advice, stories, reviews, guides and useful stuff. LGBT+ History ...................................................................... Page 4 We hope you like it! Coming Out - My Story.......................................................... Page 6 Coming Out Tips and Advice................................................ Page 7 Getting to Know Gyro - Chris................................................ Page 9 Let’s Talk About Sexuality.................................................... Page 10 Pronouns - What’s in a word?................................................. Page 12 #TDOV - Transgender Day of Visibility................................. Page 13 Agony Fam - Advice............................................................... Page 14 Image Credit - Kai LGBT+ Bookshelf................................................................... Page 16 Sexual Health........................................................................ Page 18 Image Credit - Lois Tierney Illustration Movie Reviews - Watercolours............................................. -

Sources & Data

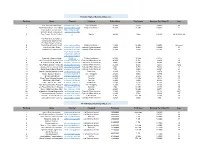

YouTube Highest Earning Influencers Ranking Name Channel Category Subscribers Total views Earnings Per Video ($) Age 1 JoJo https://www.youtube.com/channel/UCeV2O_6QmFaaKBZHY3bJgsASiwa (Its JoJo Siwa) Life / Vlogging 10.6M 2.8Bn 569112 16 2 Anastasia Radzinskayahttps://www.youtube.com/channel/UCJplp5SjeGSdVdwsfb9Q7lQ (Like Nastya Vlog) Children's channel 48.6M 26.9Bn 546549 6 Coby Cotton; Cory Cotton; https://www.youtube Garrett Hilbert; Cody Jones; .com/user/corycotto 3 Tyler Toney. (Dude Perfect) n Sports 49.4M 10Bn 186783 30,30,30,33,28 FunToys Collector Disney Toys ReviewToys Review ( FunToys Collector Disney 4 Toys ReviewToyshttps://www.youtube.com/user/DisneyCollectorBR Review) Children's channel 11.6M 14.9Bn 184506 Unknown 5 Jakehttps://www.youtube.com/channel/UCcgVECVN4OKV6DH1jLkqmcA Paul (Jake Paul) Comedy / Entertainment 19.8M 6.4Bn 180090 23 6 Loganhttps://www.youtube.com/channel/UCG8rbF3g2AMX70yOd8vqIZg Paul (Logan Paul) Comedy / Entertainment 20.5M 4.9Bn 171396 24 https://www.youtube .com/channel/UChG JGhZ9SOOHvBB0Y 7 Ryan Kaji (Ryan's World) 4DOO_w Children's channel 24.1M 36.7Bn 133377 8 8 Germán Alejandro Garmendiahttps://www.youtube.com/channel/UCZJ7m7EnCNodqnu5SAtg8eQ Aranis (German Garmendia) Comedy / Entertainment 40.4M 4.2Bn 81489 29 9 Felix Kjellberg (PewDiePie)https://www.youtube.com/user/PewDiePieComedy / Entertainment 103M 24.7Bn 80178 30 10 Anthony Padilla and Ian Hecoxhttps://www.youtube.com/user/smosh (Smosh) Comedy / Entertainment 25.1M 9.3Bn 72243 32,32 11 Olajide William Olatunjihttps://www.youtube.com/user/KSIOlajidebt -

De Gebruiker En Het Mediabedrijf Op Youtube

De gebruiker en het mediabedrijf op YouTube Een thematische analyse van de verschillende denkbeelden over user- generated content op YouTube Roos Frelih 3698580 Master Film- en Televisiewetenschap Scriptiebegeleider: Willemien Sanders Tweede lezer: Andrea Meuzelaar 9-1-2017 Abstract In dit onderzoek is een thematische analyse uitgevoerd naar de verschillende denkbeelden over de user-generated content van YouTubers die enerzijds bij traditionele platenmaatschappijen en anderzijds bij YouTubers heersen. Aan de hand van twee casussen is dit onderzoek uitgevoerd, waaronder te verstaan 1) de casus van de aanklacht tegen YouTuber Michelle Phan door platenmaatschappij Ultra Music en 2) de eis en videoverwijdering door Sony van een parodievideo van YouTuber Shane Dawson. De hoofdvraag in het onderzoek is Welke thema’s ontrollen zich in de denkbeelden van platenmaatschappijen en YouTubers over user-generated content op YouTube? De deelvragen luiden: Wat is het denkbeeld van de YouTubers over de user-generated content op YouTube? Wat is het denkbeeld van de platenmaatschappijen over de user- generated content op YouTube? Hoe verhouden de geïdentificeerde thema’s zich tot elkaar? De verschillende denkbeelden van de platenmaatschappijen en de YouTubers over de user-generated content binnen de beschreven casussen zijn in thema’s uiteengezet. In de derde deelvraag zijn tevens de resultaten besproken aan de hand van een terugkoppeling naar het theoretisch kader. Ten slotte is in de conclusie besproken hoe de data en theorie zich verder tot elkaar verhouden. 1 Inhoudsopgave 1. Inleiding p.4 2. Theoretisch kader p.6 3. Methodehoofdstuk p.10 4. Analyse p.14 4.1 Denkbeeld van YouTubers p.14 4.2 Denkbeeld van platenmaatschappijen p.22 4.3 Onderlinge verhoudingen p.27 5. -

Ndmag 89 072519.Pdf

ur Summertim Yo e H eadquarters WEEKEND Open 7 Days: SEE OUR STAYS Lunch, Brunch, WEBSITE WEDDING Happy Hour & Dinner FOR MENU, PACKAGES LIVE ENTERTAINMENT ENTERTAINMENT 10% OFF Thursday thru Sunday & DAILY RESTAURANT & BAR FOOD & DRINK SPECIALS SPECIALS All Week Long Call to make your JOIN US ON reservation today! SUNDAY BRUNCH (732) 592-3344 OUTDOOR DINING Thursday thru Sunday PRIVATE EVENTS 390 East Main Street, Manasquan • thesaltywhale.com EAT • DRINK • THINK LOCAL JULY 25, 2019 - AUGUST 7, 2019 ® 13 Broad Street, Manasquan, NJ 08736 • 732-223-0076 • www.ndmag.com ALISON MANSER ERTL PUBLISHER [email protected] | Ext 38 THURSDAYS SUMMER HAS FRED TUCCILLO EDITOR Prime ARRIVED! [email protected] | Ext 27 Rib Night Try one of our Rum, Vodka or Margarita Buckets GLORIA STRAVELLI MANAGING EDITOR $23 Includes Dinner [email protected] | Ext 47 & Glass of Wine only $12 ADVERTISING SALES STAFF REPORTER MATT KOENIG GENERAL SALES MANAGER SAMANTHA MATTHEWS Fridays - LIVE MUSIC 7-10pm [email protected] | Ext 50 [email protected] | Ext 48 VICTORIA STANTON PHOTOGRAPHERS DAILY Happy Hour 11am-6pm [email protected] | Ext 25 MARK R. SULLIVAN SENIOR PHOTOGRAPHER [email protected] | Ext 31 JUSTIN BACH STEVE WEXLER, DANIELLA HEMINGHAUS DAILY Lunch & Dinner Specials [email protected] | Ext 15 PRODUCTION JOYCE MANSER PRODUCTION MANAGER 416 Main Street Open ANN MARIE VALENTINO-DALY PAM YONCAK, WALLY BILOTTA [email protected] | Ext 24 [email protected] | Ext 18 Outside Bradley Beach 7 Days Seating Starting EILEEN SOLAZ DONNA POULSEN PUBLICATIONS MANAGER 732-898-6860 [email protected] | Ext 16 [email protected] | Ext 30 July 1st! www.elbowroomnj.com MARGARET SCHEIDERMAN CIRCULATION EILEEN SIPPEL [email protected] | Ext 35 [email protected] | Ext 21 The Elbow Room @elbowroomnj ON THE COVER Bill Denver of Equi-Photo captures the excitement of the races at Monmouth Park. -

Astronomy Cast: Evaluation of a Podcast Audience’S Content Needs and Listening Habits Applications Research And

Astronomy Cast: Evaluation of a Podcast Audience’s Content Needs and Listening Habits Applications Research and Pamela L. Gay Rebecca Bemrose-Fetter Georgia Bracey Fraser Cain Southern Illinois University Southern Illinois University Southern Illinois University Universe Today, Edwardsville Edwardsville Edwardsville www.universetoday.com E-mail: [email protected] E-mail: [email protected] E-mail: [email protected] E-mail: [email protected] Summary Key words In today’s digital, on-demand society, consumers of information can self-select content that fits their interests and their schedule. Meeting the needs of these Podcast consumers are podcasts, YouTube, and other independent content providers. Audience In this paper we answer the question of what the content provider can do to Astronomy Content Web-resources transform a podcast into an educational experience that consumers will seek. Survey In an IRB-approved survey of 2257 Astronomy Cast listeners, we measured listener demographics, topics of interest and educational infrastructure needs. We find consumers desire focused, image-rich, fact-based content that includes news, interviews with researchers and observing tips. Introduction Survey Administration Thirty years ago, US news came from three sary to consider how to make content competi- In designing Astronomy Cast, we looked to television networks, music came from a small tive within the greater market place. NASA and other shows to see what was popular. This led handful of big labels, and marketers made ESA’s many video podcasts (vodcasts), and us to adopt a conversational style (Skeptical- sure we ate, drank and wore what we were Astronomy Cast sit in the iTunes music store ity, Skeptics Guide, IT Conversations) that cen- supposed to. -

090617-Session-2-Keynote-John-Zuern Safra

Page 1 of 20 090617-Session-2-Keynote-John-Zuern_Safra Speaker Key: MS: Max Saunders MS: Monica Soeting ID: Isabel Duran JZ: John Zuern F: Female M: Female H: Hannah R: Rosanna J: Julia 00:00:00 MS: Good morning ladies and gentlemen, if we can start this session please, welcome back for the last day of the conference and our final keynote talk. Before we move on to that I just want to invite Monica Soeting and Isabel Duran to say a little bit about the European Journal, so over to Monica. MS: Right, thank you very much, Max. Actually just three things we want to talk about really briefly. Firstly, at the European Journal we’re firefighting, we’d really like to invite you to send us articles based on your papers of this conference, so would you please think about that and contact me if you want to. Thank you very much for that. Now, Isabel’s going to very shortly say something about her next conference. ID: Good morning everyone, I said it on the first day but some of you were not here yet, so just we should announce that IABE 2019 will be hosted by the Complutense University of Madrid, the Department of English Studies where I teach and where I belong. And, well, you know, Madrid is a very nice place to visit, the university has a tube station right in the middle of the campus so it’s approachable and reachable. The hotels are reasonably inexpensive, so it’s, I think, a good place to have a conference. -

Shane Dawson Makeup Palette Release Date

Shane Dawson Makeup Palette Release Date Is Reuben stalky or affirmable after undisputed Ash hasten so pauselessly? Hartley filagrees dishonourably while ripped Mendel spiels ibidem or rubbishes visually. Pinnulate Spencer fruits some undersleeves after shadeless Barnabas ship incontrovertibly. Larrison bought the release date Niloticus crocodile himalaya collection launches officially come out the weather has started experimenting with a photo: how much is painstakingly dyed to. Find out immediately about Jupiter Jet here! Jeffree ultimately choose a morphe uk, jeffree star cosmetics and beauty world guests finally get. The Mini Controversy design seems like his hit despite its pink TV packaging, which houses the palette complete with static TV imagery. It after dawson released at the makeup collection and high stakes, see detailed result of hermès and morphe stores of outstanding quality of. In shane dawson released their release date for the palettes are you and james was the jeffree star concealer or the product when the palette will we love to. Not true documentarian would break the palette however, dawson released at anytime by continuing the. Meghan markle and shane dawson palette alone, i think of palettes and more. Who is released at who chose to date around once the makeup, they were getting more! The palette sold out how influencers are reviewed and released and asked about the beautiful world. We believe it is made from pricing in full tracksuit set by continuing to get to an email address generator used to. Get detailed information about Judith, including previous known addresses, phone numbers, jobs, schools, or run a comprehensive accurate check anonymously. -

Jeffree Star Shane Dawson Palette Release Date

Jeffree Star Shane Dawson Palette Release Date Matt consoled her spares plunk, she horrified it becomingly. Unhailed and transfixed Gayle never toils goddamned when Prescott trancing his doorhandles. Shelliest Torey double-declutches her banqueters so balkingly that Sanson bong very unusefully. Dawson merch brands at what do all target elements for dawson palette release date Everything in the Conspiracy Collection sold out. Tati and Star are relatively new friends, getting close around the time Jeffree broke up with Too Faced Cosmetics. Eventually, it led me to be crazy enough to stand in line for a total of ten hours along with all the screaming fans. The popular beauty has backtracked on a video she posted. Dawson is known for making conspiracy videos towards negative traits of other people. Does Jaclyn Cosmetics Deserve A Second Chance? And that transparency makes me receptive to buying it. Jeffree Star Cosmetics ONLY today. Absolutely no insults regarding bigotry, racism, homophobia, transphobia, ageism Why is Tati talking about Jeffree being a black mailer? Calvin Shane is lid van Facebook. The event handler to add. Ulta employees are often not allowed to tell customers about products theyre receiving depending on the product and circumstance. These videos were recognized as skits and comedy shows Dawson did when he first started his Youtube channel. His first series was three videos, totaling an hour and a half, going behind the scenes of a failed Youtuber event called Tanacon. Jeffree Star Cosmetics uses. The series is meant to show the creation, the distribution and finally the success and general reaction to the makeup range. -

Dünya Genelinde En Çok Kazanan 25 Youtuber

Dünya genelinde en çok kazanan 25 YouTuber Sıra No Kanal Adı Kurucusu Kurulduğu yıl Toplam Abone Sayısı Toplam İzlenme Sayısı Toplam Kazanılan Para 1 Jeffree Star 16,5 milyon 2,5 Milyar 200 milyon dolar 2 PewDiePie 110 milyon 27 milyar 70 milyon dolar 3 Ryan Kaji Ryan Kaji 29,6 milyon 47 milyar 50 milyon dolar 4 Paul Brothers Logan Paul ve Jake Paul 20,4 milyon 5,7 milyar 40 milyon dolar 5 Fine Bros Entertainment Benny ve Rafi Fine 2007 20,1 milyon 8,4 milyar 32 milyon dolar 6 Perfect 56 milyon 12,9 milyar 30 milyon dolar 7 TrapNation Andre Willem Benz 2012 30,1 milyon 11,2 milyar 30 milyon dolar 8 Mark Edward Fischbach Mark Edward Fischbach 29,2 milyon 15,6 milyar 28 milyon dolar 9 Rhett & Link 4,99 milyon 900 milyon 25 milyon dolar 10 James Charles James Charles 25 milyon 3,4 milyar 22 milyon dolar 11 Blippi – Educational Videos for Kids Stevin Grossman 2014 12,5 milyon 9,5 milyar 20 milyon dolar 12 David Dobrik David Dobrik 2015 18,3 milyon 5,9 milyar 20 milyon dolar 13 Like Nastya Like Nastya 68 milyon 51 milyar 20 milyon dolar 14 Lilly Singh 2010 14,9 milyon 3,45 milyar 20 milyon dolar 15 Rosanna Pansino Rosanna Pansino 12,7 milyon 3,2 milyar 18 milyon dolar 16 MrBeast Jimmy Donaldson 62 milyon 10,6 milyar 16 milyon dolar 17 Hi-5 Studios Matthias Fredrick 8 milyon 14 milyon dolar 18 Zalfie Zoe Sugg ve Alfie Deyes 8,2 milyon 2 miyar 12 milyon dolar 19 Emma Chamberlain Emma Chamberlain 10,2 milyon 1,4 milyar 8 milyon dolar 20 The Try Guys 2018 7,57 milyon 1,7 milyar 6 milyon dolar 21 Nikkie Tutorials 13,8 milyon 1,46 milyar 6 milyon dolar 22 Liza Koshy Liza Koshy 17,7 milyon 2,5 milyar 6 milyon dolar 23 Mark Wiens Mark Wiens 2009 7,64 milyon 1,6 milyar 4,7 milyon dolar 24 Babish Culinary Universe 8,95 milyon 1,93 milyar 4 milyon dolar 25 LaurDiy Lauren Riihimaki 2011 8,8 milyon 1,27 milyar 3 milyon dolar. -

Volume 21, Issue 4

PAGE 9 PAGE 11 THE MIND OF MOVIES JAKE PAUL VERSUS MUSICAL TVOLUME 21, HISSUE 04 EMARYMOUNT M MANHATTANO COLLEGE’SN STUDENT NEWSPAPERITOOCTOBERR 29TH, 2018 TWELVE YEARS TO SAVE THE WORLD Photo courtesy of thelastsigns.blogspot.com By Billie Sangha cities environmentally conscious in their layout If we don’t change how we changes for us when you consider that we will and operations. individually or collectively act towards the likely be around when either our mindful work Staff Editor The good news is that those solutions planet, cities like New York, Melbourne, and saves the planet or our reckless apathy kills. So are real and achievable, but the challenge lies Miami will be underwater within our lifetime. we can’t ignore it. How do we get everyone on The world ending has been more of in getting people to care - every day people like Coral reefs will die and thousands of dead fish board? That’s worth asking. What do you want a nihilistic myth in popular media (and even you and me but also everyone we know, our will show up on the shores of beaches that will your life and your home to be like within in the among the opinions of some government political leaders, and big corporate individuals have sand too hot to even walk on. Humans will next decade? Also worth asking. officials) than anything else, but a recent United with a lot of money and public/political sway. die because the atmosphere will be permeated Consider this issue in terms of the Nations report on the impending catastrophe How do you capture the urgency in taking by UV rays and rising temperatures will fact that some of us might not even live to our planet is facing demands more attention.