ROYSTER, JR., ALBERT L., Ed.D. the Plight of the African

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

2019-2020 Fact Book

TABLE OF CONTENTS INSTITUTIONAL PROFILE 2 Fall Enrollment by Full-Time/Part-Time Status ......................22 Degrees and Certificates Awarded ..........................................22 History ........................................................................................3 Contact Hour Data ....................................................................22 Strategic Plan .............................................................................6 Pre-College Enrollment ...........................................................23 Productive Grade Rate .............................................................23 COMMUNITY EMPOWERMENT 8 Graduation Rate by FTIC Cohort ..............................................23 Palomino Park and Community Garden Open ...........................8 Course Completion Rate ..........................................................23 Engaging Community Partners .................................................8 Persistence Rate ......................................................................23 First Time in College Students Who Transfer to a Texas Senior Institution .................................................................................23 EMPLOYEE EMPOWERMENT 10 Performance Excellence Affirmed ...........................................10 BUDGET 24 PACE Survey .............................................................................11 Schedule of Tuition and Fees ...................................................24 FY 2019 Allocations ..................................................................25 -

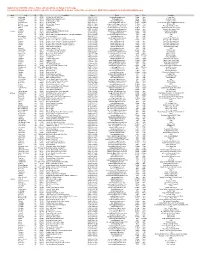

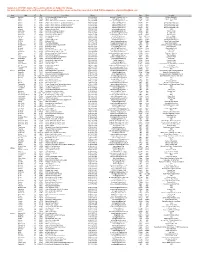

PHR Local Website Update 4-25-08

Updated as of 4/25/08 - Dates, Times and Locations are Subject to Change For more information or to confirm a specific local competition, please contact the Local Host or MLB PHR Headquarters at [email protected] State City ST Zip Local Host Phone Email Date Time Location Alaska Anchorage AK 99508 Mt View Boys & Girls Club (907) 297-5416 [email protected] 22-Apr 4pm Lions Park Anchorage AK 99516 Alaska Quakes Baseball Club (907) 344-2832 [email protected] 3-May Noon Kosinski Fields Cordova AK 99574 Cordova Little League (907) 424-3147 [email protected] 26-Apr 10am Volunteer Park Delta Junction AK 99737 Delta Baseball (907) 895-9878 [email protected] 6-May 4:30pm Delta Junction City Park HS Baseball Field Eielson AK 99702 Eielson Youth Program (907) 377-1069 [email protected] 17-May 11am Eielson AFB Elmendorf AFB AK 99506 3 SVS/SVYY (907) 868-4781 [email protected] 26-Apr 10am Elmendorf Air Force Base Nikiski AK 99635 NPRSA 907-776-8800x29 [email protected] 10-May 10am Nikiski North Star Elementary Seward AK 99664 Seward Parks & Rec (907) 224-4054 [email protected] 10-May 1pm Seward Little League Field Alabama Anniston AL 36201 Wellborn Baseball Softball for Youth (256) 283-0585 [email protected] 5-Apr 10am Wellborn Sportsplex Atmore AL 36052 Atmore Area YMCA (251) 368-9622 [email protected] 12-Apr 11am Atmore Area YMCA Atmore AL 36502 Atmore Babe Ruth Baseball/Atmore Cal Ripken Baseball (251) 368-4644 [email protected] TBD TBD TBD Birmingham AL 35211 AG Gaston -

Regional Contest Schedules Made

aiaijaa^ia(Dii(M(3 isaQoaa VOL. XL AUSTIN, TEXAS, MARCH, 1957 NO. 7 Debaters Pick Regional Contest Topic On 'Aid' The balloting on the debate areas tion, the question of agency is not for next year has been completed by the factor that is of prime import the National University Extension ance as it is in the proposition using Schedules Made Association Committee on Discus the United Nations as the agency. Directors general of all Regional P. Merville Larson, Texas Tech. 10:00 a.m.—Shorthand, Agriculture sion and Debate Materials. The win Here the major discussion would in Meets have announced their tenta For: conference AA: districts 1-5, Building 301. ning area, with 29 first place votes volve a review of the present aid to tive schedules for the April 12-13 inclusive; conference A: districts 1- Poetry reading, Science Build from the 43 states participating in other countries, the benefits that weekend and all schools qualifying 4, inclusive; conference B: districts ing 221. the voting, was: have accrued to them and to the contestants from their districts are 1-18, inclusive. 10:30 a.m.—Extemporaneous speak What Should Be the Nature of United States by such aid, and the urged to contact the Regional Di ing, Main Auditorium. April 12 United States Foreign Aid ? advisability of increasing- such aid rector of their respective regions Number sense, Science Build > Texas schools will be sent a ballot in the future. for an official and final contest 8:45 a.m.—Conference B tennis pre ing 353. ,X very shortly listing the three sug The opponents of this measure schedule. -

Appendices to the Reporting and Procedures Manual

APPENDICES to the REPORTING and PROCEDURES MANUALS for Texas Universities, Health-Related Institutions, Community, Technical, and State Colleges, and Career Schools and Colleges Fall 2009 TEXAS HIGHER EDUCATION COORDINATING BOARD Educational Data Center TEXAS HIGHER EDUCATION COORDINATING BOARD APPENDICES TEXAS UNIVERSITIES, HEALTH-RELATED INSTITUTIONS, COMMUNITY, TECHNICAL, AND STATE COLLEGES, AND CAREER SCHOOLS Revised Fall 2009 For More Information Please Contact: Doug Parker Educational Data Center Texas Higher Education Coordinating Board P.O. Box 12788 Austin, Texas 78711 (512) 427-6287 FAX (512) 427-6447 [email protected] The Texas Higher Education Coordinating Board does not discriminate on the basis of race, color, national origin, gender, religion, age or disability in employment or the provision of services. TABLE OF CONTENTS A. Institutional Code Numbers for Texas Institutions Page Public Universities ...................................................................................................... A.1 Independent Senior Colleges and Universities .......................................................... A.2 Public Community, Technical, and State Colleges .................................................... A.3 Independent Junior Colleges ..................................................................................... A.5 Texas A&M University System Service Agencies ...................................................... A.5 Health-Related Institutions ........................................................................................ -

County of Dare

COUNTY OF DARE PO Box 1000, Manteo, NC 27954 DARE COUNTY BOARD OF COMMISSIONERS Dare County Administration Building 954 Marshall C. Collins Dr., Manteo, NC Monday, June 21, 2021 “HOW WILL THESE DECISIONS IMPACT OUR CHILDREN AND FAMILIES?” AGENDA 5:00 PM CONVENE, PRAYER, PLEDGE OF ALLEGIANCE ITEM 1 Opening Remarks - Chairman's Update ITEM 2 Employee of the Month ITEM 3 Public Comments ITEM 4 Public Hearing -- Chapter 160D Amendments to Various Ordinances ITEM 5 Dare County Home Health & Dare Hospice ITEM 6 FY2022 Budget Amendment for Home Health and Hospice ITEM 7 Budget Amendments Required by LGC Memo 2021-04 for GASB Statements #’s 84 & 97 ITEM 8 RFQ for Professional Architectural Services ITEM 9 Consent Agenda 1. Approval of Minutes 2. Tax Collector's Report 3. Budget Amendment for Holiday and Comp Time Payout Approved on 5/17/2021 4. Reimbursement Resolutions - Fiscal Year 2021-2022 Vehicle & Equipment Financing Fiscal Year 2021-2022 Public Works Equipment Financing 5. NCDEQ Grant Contract 8161 and 8162 Budget Amendment 6. Avon Property Owner's Association July 4th Celebration 7. Request to Approve Grant Application- Sheriff's Dept. 8. NCDOT Right of Way Three Party Encroachment Agreement for Dare Challenge Project ITEM 10 Board Appointments 1. Game and Wildlife Commission 2. Wanchese Community Center 3. East Lake Community Center Board ITEM 11 Commissioners' Business & Manager's/Attorney's Business ADJOURN UNTIL 5:00 P.M. ON JULY 19, 2021 3 Opening Remarks - Chairman's Update Description Dare County Chairman Robert Woodard will make opening remarks. Board Action Requested Informational Presentation Item Presenter Chairman Robert Woodard, Sr. -

Arthenon University Archives

Marshall University Marshall Digital Scholar The Parthenon University Archives Summer 6-23-1966 The Parthenon, June 23, 1966 Marshall University Follow this and additional works at: https://mds.marshall.edu/parthenon Recommended Citation Marshall University, "The Parthenon, June 23, 1966" (1966). The Parthenon. 1278. https://mds.marshall.edu/parthenon/1278 This Newspaper is brought to you for free and open access by the University Archives at Marshall Digital Scholar. It has been accepted for inclusion in The Parthenon by an authorized administrator of Marshall Digital Scholar. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. 'One Board Necessary To Progress' By RON HITE Higher Education is preparing a proposal bers who feel that the administration has has in its brief period of existence pre Editor-in-Chief which will be submitted to the next ses not ''adequately cared for their interests." pared a master plan for higher education "West Virginia needs a single board of sion of the Legislature asking that the Dr. Smith in support of a single board in the state. It has also approved degrees higher education whose primary function role of higher education in the state be of regents for the state has emphasized and master degrees programs, establish is planning, programming and coordinat taken out of the hands of the Board of that with the increased growth of educa ment of new university branches, and has ing the work of all our state-supported Education and instead, be placed under tion in general in the state, the Board of conducted numerous s u r v e y s of state co 11 e g es and universities," President a board of regents. -

PHR Local Website Update 3-7-08

Updated as of 3/7/08 - Dates, Times and Locations are Subject to Change For more information or to confirm a specific local competition, please contact the Local Host or MLB PHR Headquarters at [email protected] State City ST Zip Local Host Phone Email Date Time Location Alabama Anniston AL 36201 Wellborn Baseball Softball for Youth (256) 283-0585 [email protected] 5-Apr 10am Wellborn Sportsplex Atmore AL 36052 Atmore Area YMCA (251) 368-9622 [email protected] 12-Apr 11am Atmore Area YMCA Atmore AL 36502 Atmore Babe Ruth Baseball/Atmore Cal Ripken Baseball (251) 368-4644 [email protected] TBD TBD TBD Dothan AL 36302 Dothan Leisure Services - Dothan American LL (334) 615-3700 [email protected] 23-Apr 6pm Doug Tew Baseball Park Dothan AL 36302 Dothan Leisure Services - Dothan International LL (334) 615-3700 [email protected] 23-Apr 6pm Doug Tew Baseball Park Dothan AL 36302 Dothan Leisure Services - Dothan National LL (334) 615-3700 [email protected] 23-Apr 6pm Doug Tew Baseball Park Dothan AL 36302 Dothan Leisure Services - Dothan Southern LL (334) 615-3700 [email protected] 23-Apr 6pm Doug Tew Baseball Park Elkmont AL 35620 Ardmore Booster Club (256) 683-3978 [email protected] TBD TBD TBD Gardendale AL 35071 Gardendale Parks & Recreation (205) 631-4797 [email protected] 4-May 6pm Moncrief Park Greenville AL 36037 Greenville Parks & Recreation (334) 382-3031 [email protected] 16-Apr 4pm Beeland Park Guntersville AL 35976 Guntersville Parks and Rec (256) 571-7590 [email protected] -

Nov/Dec Leaguer

JAN/FEB. 2003 Volume 87 • Number 4 UNIVERSITY INTERSCHOLASTIC LEAGUE ○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○ ○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○Leaguer ReflectionsReflections ofof SuccessSuccess Top 15 give students credit for successes hether it be in sports, music or academics, most Texas teachers know that their biggest success comes with the success of their stu- dents. UIL recognizes this concept and 13 Wyears ago created an award to recognize 15 teachers/sponsors who go “above and be- yond” to make their students successful with the UIL Sponsor Excellence Award. A panel of judges representing the areas of music, academics and athletics selected the winners from nominees submitted by school principals and superintendents state- A Little Extra Help wide. Nomination forms were sent to schools Sponsor Excellence Award winner in August. Mariann Fedrizzi of Cypress Creek High The award was created to identify and School in Houston helps junior Keith recognize outstanding sponsors who assist Jones with research. Fedrizzi serves as students in developing and refining their the fine arts department chair and is extra-curricular talents to the highest de- running the UIL academic meet this gree possible within the educational sys- spring. Fifteen sponsors in academics, tem, while helping to keep their personal music and sports are recognized by the worth separate from their success or failure UIL each year with the Sponsor Excel- in competition. lence Award. Each recipient receives “The benefits of interscholastic compe- $1,000 and a plaque to display his or tition and student performance are made her accomplishments. possible by dedicated directors, sponsors photo courtesy of Mary Beth Kerr, Cypress Creek High School Publications and coaches,” UIL Director Dr. -

House Journal Eighty-Third Legislature, First Called Session

HOUSE JOURNAL EIGHTY-THIRD LEGISLATURE, FIRST CALLED SESSION PROCEEDINGS SIXTH DAY (CONTINUED) - TUESDAY, JUNE 25, 2013 The house met at 1 p.m. and was called to order by the speaker. The roll of the house was called and a quorum was announced present (Record 56). Present - Mr. Speaker; Allen; Alonzo; Alvarado; Anderson; Ashby; W Aycock; Bell; Bohac; Bonnen, D.; Bonnen, G.; Branch; Burkett; Burnam; Button; Callegari; Canales; Capriglione; Carter; Clardy; Coleman; Collier; Cook; Cortez; Craddick; Creighton; Crownover; Dale; Darby; Davis, J.; Davis, S.; Davis, Y.; Deshotel; Dukes; Dutton; Eiland; Elkins; Fallon; Farias; Farney; Farrar; Fletcher; Flynn; Frank; Frullo; Geren; Giddings; Goldman; Gonzales; Gonzilez, M.; Gonzalez, N.; Gooden; Guerra; Guillen; Gutierrez; Harper-Brown; Hernandez Luna; Herrero; Hilderbran; Howard; Huberty; Hughes; Hunter; Isaac; Johnson; Kacal; Keffer; King, K.; King, P.; King, S.; King, T.; Kleinschmidt; Klick; Kolkhorst; Krause; Kuempel; Larson; Laubenberg; Lavender; Leach; Lewis; Longoria; Lozano; Lucio; Martinez; Martinez Fischer; McClendon; Menendez; Miles; Miller, D.; Miller, R.; Moody; Morrison; Munoz; Murphy; Naishtat; Nevirez; Oliveira; Orr; Otto; Paddie; Parker; Patrick; Perez; Perry; Phillips; Pickett; Pitts; Price; Ratliff; Raymond; Reynolds; Riddle; Ritter; Rodriguez, E.; Rodriguez, J.; Rose; Sanford; Schaefer; Sheets; Sheffield, J.; Sheffield, R.; Simmons; Simpson; Smith; Smithee; Springer; Stephenson; Stickland; Strama; Taylor; Thompson, E.; Thompson, S.; Toth; Turner, C.; Turner, ES.; Villalba; Villarreal; Vo; Walle; White; Workman; Zedler; Zerwas. Absent, Excused Anchia; Harless; Raney; Turner, S.; Wu. Absent Marquez. The speaker recognized Representative Perry who offered the invocation. The speaker recognized Representative Perry who led the house in the pledges of allegiance to the United States and Texas flags. LEAVES OF ABSENCE GRANTED The following members were granted leaves of absence for today because of important business in the district: Harless on motion of Alvarado. -

Appendices to the Reporting and Procedures Manual for Texas

APPENDICES to the REPORTING and PROCEDURES MANUALS for Texas Universities, Health-Related Institutions, Community, Technical, and State Colleges, and Career Schools and Colleges Fall 2007 TEXAS HIGHER EDUCATION COORDINATING BOARD Educational Data Center TEXAS HIGHER EDUCATION COORDINATING BOARD APPENDICES TEXAS UNIVERSITIES, HEALTH-RELATED INSTITUTIONS, COMMUNITY, TECHNICAL, AND STATE COLLEGES, AND CAREER SCHOOLS Revised Fall 2007 For More Information Please Contact: Doug Parker Educational Data Center Texas Higher Education Coordinating Board P.O. Box 12788 Austin, Texas 78711 (512) 427-6287 FAX (512) 427-6447 [email protected] The Texas Higher Education Coordinating Board does not discriminate on the basis of race, color, national origin, gender, religion, age or disability in employment or the provision of services. TABLE OF CONTENTS A. Institutional Code Numbers for Texas Institutions Page Public Universities ...................................................................................................... A.1 Independent Senior Colleges and Universities .......................................................... A.2 Public Community, Technical, and State Colleges .................................................... A.3 Independent Junior Colleges ..................................................................................... A.5 Texas A&M University System Service Agencies ...................................................... A.5 Health-Related Institutions ........................................................................................ -

Uiw W Omen's B Asketb All 2 014-15

UIW WOMEN’S BASKETBALL 2014-15 BASKETBALL UIW WOMEN’S www.uiwcardinals.com 1 UIW WOMEN’S BASKETBALL 2014-15 BASKETBALL UIW WOMEN’S 2014-15 SEASON SCHEDULE Date Opponent Location Conf. Time Nov. 14 Texas Wesleyan McDermott Center 6:00 Nov. 17 Houston Houston, TX 7:00 Nov. 20 St. Thomas McDermott Center 6:00 Nov. 23 Indiana Bloomington, IN 2:00 Nov. 28 Fordham San Antonio, TX 12:00 Nov. 30 UTSA San Antonio, TX 4:30 Dec. 4 Kansas Lawrence, KS 7:00 Dec. 10 Texas Lutheran McDermott Center 6:00 Dec. 15 Our Lady of the Lake McDermott Center 6:00 Dec. 18 UT-Pan American Edinburg, TX 7:00 Dec. 30 Grand Canyon McDermott Center 6:00 Jan. 3 Sam Houston State Huntsville, TX SLC 2:00 Jan. 8 New Orleans McDermott Center SLC 6:00 Jan. 10 Northwestern State Natchitoches, LA SLC 1:00 Jan. 17 Southeastern Louisiana McDermott Center SLC 2:00 Jan. 22 McNeese State McDermott Center SLC 6:00 Jan. 24 Abilene Christian Abilene, TX SLC 2:00 Jan. 29 Texas A&M-Corpus Christi Corpus Christi, TX SLC 7:00 Jan. 31 Nicholls Thibodaux, LA SLC 1:00 Feb. 4 Nicholls McDermott Center SLC 6:00 Feb. 7 Lamar McDermott Center SLC 5:00 Feb. 12 Stephen F. Austin McDermott Center SLC 6:00 Feb. 15 Central Arkansas Conway, AR SLC 1:00 Feb. 19 Houston Baptist Houston, TX SLC 6:00 Feb. 21 Texas A&M-Corpus Christi McDermott Center SLC 2:00 Feb. 26 Stephen F. Austin Nacogdoches, TX SLC 7:00 Feb. -

Il N T E Mchojastic LEAGUER

il N T E MCHOjASTiC LEAGUER VOL. XXXVII AUSTIN, TEXAS, SEPTEMBER, 1954 NO. I Rule Book Changes Dallas, Houston Conferences By League Noted Draw Students Oct. 16, 23 Attention is called to a number Some important rule changes Barry Holton, public relations; Dr. public relations; Dr. Otis Walter, of revisions in the 1954-55 Con have been made, however. All roads in North and Southeast First on tap is the North Texas James H. Mailey, chairman of speech chairman; Miss Lela Blount, stitution and Rules. School ex Rule 6c of the Boys' Basketball Texas lead to the Student Ac Student Activities Conference. at secondary education department; drama chairman; Bruce Under ecutives, coaches and teachers Plan now provides that district tivities Conferences at Dallas and Southern Methodist University on Dr. Bob G. Woods, assistant pro wood, journalism chairman. should acquaint themselves with games may not be played prior to Houston on Oct. 16 and 23, re Saturday, Oct. 16, under direction fessor of education; E. L. Callihan, the rearrangement of certain sec December 15, 1954, except by un spectively. of Bob McKay, assistant superin Tentative plans for the Houston chairman of journalism depart tions of the rules. animous consent of all district Plans are about complete for tendent of Dallas public schools. meeting call for a general session these first two of the year's student SMU faculty and staff have been ment; and Dr. Harold Weiss, chair at 8 a.m., opened with 30 minutes For several years the State Ex members. conference schedule, and all signs busy for several weeks, planning a man, speech department.