Embassy of the Future

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Griffin, George G.B

The Association for Diplomatic Studies and Training Foreign Affairs Oral History Project GEORGE G. B. GRIFFIN Interviewed by: Charles Stuart Kennedy Initial interview date: April 30, 2002 Copyright 2004 ADS TABLE OF CONTENTS Background Born in stanbul, Turkey; raised in Turkey, and Georgia and South Carolina Georgia Tech and the University of South Carolina U.S. Navy Entered Foreign Service - 1,5, Naples, taly - .ice Consul 1,5,-1,60 1ucky 1uciano 2ennedy visit Colombo, Ceylon - Second Secretary and .ice Consul 1,60-1,65 Hickenlooper Amendment 3elations Soviets Environment Peace Corps 4rs. Bandaranaike Ford Foundation Speaking Tour Program 1,65 State Department - Operations Center 1,65-1,66 .ietnam Operations State Department - Near East5South Asia Bureau - Southeast 1,67-1,6, Asian Affairs - Ceylon and 4aldives Desk Officer State Department - UN Political Affairs - Political Officer 1,67-1,6, Embargos Calcutta, ndia 1,6,-1,70 4rs. Gandhi ndia-Pakistan 7ar 1 Bengal Communists Environment Bhutan 4other Theresa slamabad, Pakistan - Political Officer 1,70-1,78 Bhutto Environment Government ndia-Pakistan comparison slamic fundamentalists Embassy Delhi- slamabad relations 1ahore, Pakistan - Deputy Principal Officer 1,78-1,75 Environment Bhutto 3elations Afghanistan slamic e9tremism 2ashmir State Department - Bureau of ntelligence and 3esearch - South 1,75-1,7, Asia Division ntelligence community Operations Shah troubles Ayatollah 2homeini Pakistan Embassy takeover Afghanistan Ambassador Dubs assassinated ndia nuclear program State Department -

A Foreign Affairs Budget for the Future Fixing the Crisis in Diplomatic Readiness October 2008

A Foreign Affairs Budget for the Future Fixing the Crisis in Diplomatic Readiness October 2008 Resources for US Global Engagement Full Report The American Academy of Diplomacy The American Academy of Diplomacy i Dear Colleague, The new Administration will face multiple, critical foreign challenges with inadequate diplomatic personnel and resources to carry out policy effectively. To lead the way in presenting detailed recommendations tied to specific analysis, we are very pleased to present A Foreign Affairs Budget for the Future. This study examines key elements of the resource crisis in America's ability to conduct its international programs and policies. Our study considers the 21st century challenges for American diplomacy, and proposes a budget that would provide the financial and human capacity to address those fundamental tasks that make such a vital contribution to international peace, development and security and to the promotion of US interests globally. The American Academy of Diplomacy, with vital support from the Una Chapman Cox Foundation, launched this project in 2007 and named Ambassador Thomas Boyatt as Project Chairman. The Academy turned to the Stimson Center to conduct research and draft the report. To guide key directions of the research, the Academy organized, under the leadership of former Under Secretary of State Thomas Pickering, an Advisory Group and a Red Team, comprised of distinguished members of the Academy and senior former policy makers from outside its ranks. Their participation in a series of meetings and feedback was critical in establishing the key assumptions for the study. The Stimson team was led by former USAID Budget Director Richard Nygard. -

Cruise Line Incident Reporting Statistics

GUIDE TO CRIMINAL ACTIVITY PREVENTION AND RESPONSE; MISSING PERSONS GUIDE TO CRIMINAL ACTIVITY PREVENTION AND RESPONSE; You shouldYou should immediately immediately dial the dial vessel’s the vessel’s emergencyMISSING emergency number, PERSONS number, 112, to report3333, toany report missing any person missing or personcriminal or activity. criminal activity. The vessel’s Security Department is responsible for responding to all alleged crimes and missing persons and can be contactedTheYou should directlyvessel’s immediately atSecurity any time Department by dial dialing the vessel’s 112,is responsible or emergency “0” for the for Operator. respondingnumber, 3333, to allto reportalleged anycrimes missing and personmissing orpersons andcriminal can be activity. contacted directly at any time by dialing 3333 or “0” for the Operator. The MedicalThe vessel’sMedical Center Security onDepartment Deck 4Department can on be Deckcontacted is 5responsible can atbe any contacted time for respondingalso at byany dialing time to 4222allalso alleged byor “0”dialing crimesfor the 3333 Operatorand or missing for anypersons required“0”and formedicalcan the be Operatorcontacted assistance. for directly any required at any time medical by dialing assistance. 3333 or “0” for the Operator. The WorldCrystalThe hasMedical Cruises zero toleranceDepartment has zero for tolerance crimeon Deck on for board.5 cancrime Thebe oncontacted World board is required itsat vessels.any time by UnitedOn also international byStates dialing law 3333to voyages report or tothat the embark US Federal Bureauor“0” ofdisembark for Investigation the Operator in the and Unitedfor US any Department States, required Crystal ofmedical Homeland Cruises assistance. Securityis required all seriousby federal crimes law (homicide, to report onboardsuspicious felonies death, kidnapping,Crystaland missing assault Cruises U.S. -

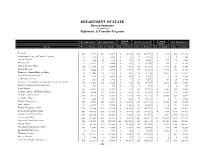

DEPARTMENT of STATE Bureau Summary ($ in Thousands) Diplomatic & Consular Programs

DEPARTMENT OF STATE Bureau Summary ($ in thousands) Diplomatic & Consular Programs Built-In Program FY 2008 Actual FY 2009 Estimate Current Services FY 2010 Request Changes Changes Bureau Pos Funds Pos Funds Pos Funds Pos Funds Pos Funds Pos Funds Secretary 480 93,129 461 113,139 0 21,626 461 108,995 23 7,563 484 116,558 Ambassador at Large for Counter-Terrorism 0 1,535 0 3,016 0 15 0 3,031 0 0 0 3,031 Chief of Protocol 64 9,190 64 9,333 0 173 64 9,506 9 747 73 10,253 Management 33 10,276 33 10,805 0 169 33 10,974 0 245 33 11,219 Political-Military Affairs 200 33,330 200 35,679 0 649 200 34,108 4 -2,123 204 31,985 Medical Director 131 38,446 131 40,829 0 7,790 131 43,619 25 7,528 156 51,147 Democracy, Human Rights and Labor 118 19,445 118 17,853 0 325 118 18,178 0 2,481 118 20,659 International Criminal Justice 10 2,135 10 2,219 0 44 10 2,263 0 0 10 2,263 Trafficking in Persons 24 4,321 24 4,483 0 74 24 4,557 2 453 26 5,010 Oceans and International Environmental and Scientific Affairs 168 31,563 168 34,132 0 642 168 34,774 0 2,143 168 36,917 Population and International Migration 0 792 0 872 0 23 0 895 0 0 0 895 Legal Advisor 255 48,552 255 49,559 0 832 255 50,391 10 5,409 265 55,800 Economic, Energy, and Business Affairs 209 34,354 209 35,663 0 665 209 36,328 4 1,683 213 38,011 Intelligence and Research 313 56,175 313 59,818 0 1,758 313 61,576 15 1,303 328 62,879 Legislative Affairs 71 11,292 71 11,801 0 220 71 12,021 0 0 71 12,021 Resource Management 357 97,751 357 106,971 0 34,040 357 141,011 11 5,145 368 146,156 Public Affairs 221 -

Dec 2006.Qxd

U.S. DEPARTMENT OF STATE MAGAZINE DECEMBER 2006 CONTENTS STATE MAGAZINE + DECEMBER 2006 + NUMBER 507 The Price of Life Student learns about medicine in Central Africa. 22 * A Critical Difference FSN of the Year supports freedom in Burma. 26 * Office of the Month: Office of Treaty Affairs Despite a small staff, L/T has a long reach. 40 * ON THE COVER The State Department marks the traditional holiday season by continuing to spread the light of freedom and truth throughout the world. Photo by Corbis Post of the Month: *Valletta Malta has complex history and exciting future. 14 10 Calgary at 100 32 Hearts, Minds and Lives Consulate marks centennial with cowboy hats. Training physicians in Yemen builds goodwill. 12 Eyes and Ears 34 Building CSI Tbilisi One-officer posts help cover France. Projects help Georgians fight crime. 20 Summer Vacation 36 The Tie That Binds Teen volunteers at Romanian orphanage. Brazil consulate celebrates historic visit. 24 Albuquerque ‘Angel’ 38 Where’s My Stapler? International visitor receives the gift of sight. State fills internships with challenging tasks. 30 Elementary, Homes 44 Home Base Consulate helps flood-ravaged Indians. Lodging program benefits FSI students. COLUMNS 2 FROM THE SECRETARY 45 STATE OF THE ARTS 3 READERS’ FEEDBACK 46 APPOINTMENTS 4 FROM THE UNDER SECRETARY 46 RETIREMENTS 5 IN THE NEWS 47 OBITUARIES 9 DIRECT FROM THE D.G. 48 THE LAST WORD FROM THE SECRETARY A Time for Reflection and Hope in Asia or Africa, in Latin America or the Middle East, we are advancing our goals of security and freedom, and we are building new partnerships with all who aspire to the universal ideals of liberty and human rights. -

Foreign Service Nationals: America's Bridge the BUREAU of HUMAN RESOURCES

About This Issue 790년 10명도 안 되는 직원으로 출범 ince its creation in 1790 with 1한 미 국무부는 복합적인 대형 기관으 fewer than ten employees, the U.S. Department of State has 로 성장했습니다. 오늘날 5만5000여 S 명의 직원들이 "미국인과 국제사회를 위해 evolved into a large, complex organ- C AP Images/Lawrence Jackson 더 안전하고 민주적이며 번영하는 세상을 ization. Today its more than 55,000 C AP Images/로렌스 잭슨 employees work together to accom- President George W. Bush and Deputy Secretary 창출한다"는 사명을 완수하고자 힘을 모으 plish the department's mission-"to of State John Negroponte in the Oval Office of the 고 있습니다. White House. create a more secure, democratic, 미 국무부는 특정 지역(아프리카, 백악관 대통령 집무실에서 조지 W. 부시 대통령과 and prosperous world for the benefit 존 네그로폰테 국무부 부장관 동아시아·태평양, 유럽·유라시아, 근동, of the American people and the 남아시아·중앙아시아 및 서반구)에 초점을 맞추는 '지역별' 부서 international community." 와, 특정 사안을 전 세계 차원에서 담당하는 '기능별' 부서로 구성 The department is organized around both 되어 있습니다. <e저널 USA> 2006년 가을호에서는 국무부 지역별 "regional" bureaus, each of which focuses on a specific 부서의 지도자들이 미국 대외정책의 목표와 우선사항에 관해 설 geographical region (Africa, East Asia and the Pacific, 명한 글들을 게재한 바 있습니다. 이번 호에서는 미국의 정책을 추 Europe and Eurasia, the Near East, South and Central 진하는 과정에서 국무부 기능별 부서가 담당하는 역할과 '글로벌 Asia, and the Western Hemisphere), and the "function- 차원의 활동(global actions)'을 소개합니다. al" bureaus, which have worldwide responsibility for particular issues. Our September 2006 eJournal USA 국무부의 현 수장은 제67대 국무장관인 콘돌리자 라이스입니다. -

The Foreign Service Journal, January 2009

“H” IS FOR HILL I ABROKEN SYSTEM I SWAN SONG $3.50 /JANUARY 2009 OREIGN ERVICE FJOURNAL STHE MAGAZINE FOR FOREIGN AFFAIRS PROFESSIONALS SLOGAN OR SUBSTANCE? The Legacy of Transformational Diplomacy OREIGN ERVICE FJOURNAL S CONTENTS January 2009 Volume 86, No. 1 F OCUSON T RANSFORMATIONAL D IPLOMACY GLOBAL REPOSITIONING IN PERSPECTIVE / 18 Global repositioning is a key element of Secretary of State Rice’s signature initiative. Here is an in-depth look at the program. By Shawn Dorman THE BRAVE NEW WORLD OF DEMOCRACY PROMOTION / 31 U.S. democracy promotion policy appears to be at a crossroads, with big divisions within both parties over how much of it we should be doing. Cover and inside illustrations By Robert McMahon by David Wink MEPI: ADDING TO THE DIPLOMATIC TOOLBOX / 40 Despite many obstacles, the Middle East Partnership Initiative has come a long way in the past five years. By Peter F. Mulrean PRESIDENT’S VIEWS / 5 Renewing American Diplomacy By John K. Naland F EATURES SPEAKING OUT / 13 Let’s Help “H” MENTAL HEALTH CARE AT STATE:ABROKEN SYSTEM / 46 Make the Case for State Foreign Service employees have incentives to hide their mental health By Stetson Sanders treatment or, worse, to let their problems go untreated. By Anonymous LETTER FROM THE EDITOR / 16 THE BLACK SWAN COMES HOME / 48 By Steven Alan Honley A letter discovered in the Embassy Paris mailroom in 2003 REFLECTIONS / 76 helped solve a 60-year-old mystery. Here is the rest of the story. Dean Rusk and Rolling Thunder By Douglas W. Wells By John J. -

Interview with George G. B. Griffin

Library of Congress Interview with George G. B. Griffin Association for Diplomatic Studies and Training Foreign Affairs Oral History Project GEORGE G. B. GRIFFIN Interviewed by: Charles Stuart Kennedy Initial interview date: April 30, 2002 Copyright 2004 ADST Q: Today is April 30, 2002. This is an interview with George Griffin. This is being done on behalf of the Association for Diplomatic Studies and Training, and I'm Charles Stuart Kennedy. Do you go by George? GRIFFIN: Sure. Q: Let's start at the beginning. When and where were you born? GRIFFIN: I was born on October 22nd, 1934, in Istanbul, Turkey, at the Admiral Bristol Hospital. Q: How come? Istanbul is not the normal place. GRIFFIN: My father was a businessman. He was in the tobacco business in Turkey. He was originally from North Carolina, and my mother was from South Carolina. He was in Turkey for 40-plus years in that business. He started in Greece, in Salonika, and then moved to Turkey, after which he got married. Because my mother had lost her first baby in Samsun, which is where they were living first, they decided she should go to a proper hospital to have me. After that, we lived Interview with George G. B. Griffin http://www.loc.gov/item/mfdipbib001355 Library of Congress in Samsun until my mother, my little sister, and I left in the summer of 1939. She was about to have another baby and thought there was a war coming, so we left. My father left Turkey in 1941. He was almost captured by the Japanese. -

A Foreign Affairs Budget for the Future Fixing the Crisis in Diplomatic Readiness October 2008

A Foreign Affairs Budget for the Future Fixing the Crisis in Diplomatic Readiness October 2008 Resources for US Global Engagement Full Report The American Academy of Diplomacy The American Academy of Diplomacy i Dear Colleague, The new Administration will face multiple, critical foreign policy challenges with inadequate diplomatic personnel and resources to carry out policy effectively. To lead the way in presenting detailed recommendations tied to specific analysis, we are very pleased to present A Foreign Affairs Budget for the Future. This study examines key elements of the resource crisis in America's ability to conduct its international programs and policies. Our study considers the 21st century challenges for American diplomacy, and proposes a budget that would provide the financial and human capacity to address those fundamental tasks that make such a vital contribution to international peace, development and security and to the promotion of US interests globally. The American Academy of Diplomacy, with vital support from the Una Chapman Cox Foundation, launched this project in 2007 and named Ambassador Thomas Boyatt as Project Chairman. The Academy turned to the Stimson Center to conduct research and draft the report. To guide key directions of the research, the Academy organized, under the leadership of former Under Secretary of State Thomas Pickering, an Advisory Group and a Red Team, comprised of distinguished members of the Academy and senior former policy makers from outside its ranks. Their participation in a series of meetings and feedback was critical in establishing the key assumptions for the study. The Stimson team was led by former USAID Budget Director Richard Nygard. -

The Embassy of the Future

THE EMBASSY OF THE FUTURE George L. Argyros Marc Grossman Felix G. Rohatyn Commission Cochairs Anne Witkowsky Project Director 1800 K Street, N.W., Washington, D.C. 20006 T (202) 775-3119 • F (202) 775-3199 • www.csis.org A B O U T C S I S The Center for Strategic and International Studies (CSIS) seeks to advance global security and prosperity in an era of economic and political transformation by providing strategic insights and practical policy solutions to decisionmakers. CSIS serves as a strategic planning partner for the government by conducting research and analysis and developing policy initiatives that look into the future and anticipate change. Our more than 25 programs are organized around three themes: Defense and Security Policy—With one of the most comprehensive programs on U.S. defense policy and international security, CSIS proposes reforms to U.S. defense organization, defense policy, and the defense industrial and technology base. Other CSIS programs offer solutions to the challenges of proliferation, transnational terrorism, homeland security, and post-conflict reconstruction. Global Challenges—With programs on demographics and population, energy security, global health, technology, and the international financial and economic system, CSIS addresses the new drivers of risk and opportunity on the world stage. Regional Transformation—CSIS is the only institution of its kind with resident experts studying the transformation of all of the world’s major geographic regions. CSIS specialists seek to anticipate changes in key countries and regions—from Africa to Asia, from Europe to Latin America, and from the Middle East to North America. Founded in 1962 by David M. -

Guide to Criminal Activity Prevention and Response; Missing Persons

GUIDE TO CRIMINAL ACTIVITY PREVENTION AND RESPONSE; MISSING PERSONS You shouldYou should immediately immediately dial the dial vessel’s the vessel’s emergency emergency number, number, 112, to report3333, toany report missing any person missing or personcriminal or activity. criminal activity. The vessel’s Security department is responsible for responding to all alleged crimes and missing persons and can be contactedThe directlyvessel’s atSecurity any time Department by dialing ext.is responsible 112, or “0” forfor theresponding Operator. to all alleged crimes and missing persons and can be contacted directly at any time by dialing 3333 or “0” for the Operator. The MedicalThe Medical Center onDepartment Deck 4 can on be Deckcontacted 5 can atbe any contacted time by atdialing any time ext. 4222also byor “0”dialing for the 3333 Operator or for any required medical“0” assistance.for the Operator for any required medical assistance. The WorldCrystal has Cruises zero tolerance has zero for tolerance crime on forboard. crime The on World board is required its vessels. by UnitedOn international States law to voyages report tothat the embark U.S. Federal BureauorGUIDE ofdisembark Investigation TO CRIMINAL in the and United ACTIVITY U.S. Department States, PREVENTION Crystal of Homeland CruisesAND RESPONSE; is Security required all byserious federal crimes law to(homicide, report onboard suspicious felonies death, kidnapping,and missing assault U.S. with nationals seriousMISSING bodily to federalPERSONS injury, agencies. sexual assaults For a