Chemonics International Consulting Division

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

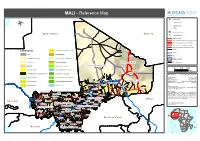

MALI - Reference Map

MALI - Reference Map !^ Capital of State !. Capital of region ® !( Capital of cercle ! Village o International airport M a u r ii t a n ii a A ll g e r ii a p Secondary airport Asphalted road Modern ground road, permanent practicability Vehicle track, permanent practicability Vehicle track, seasonal practicability Improved track, permanent practicability Tracks Landcover Open grassland with sparse shrubs Railway Cities Closed grassland Tesalit River (! Sandy desert and dunes Deciduous shrubland with sparse trees Region boundary Stony desert Deciduous woodland Region of Kidal State Boundary ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! Bare rock ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! Mosaic Forest / Savanna ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! Region of Tombouctou ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! 0 100 200 Croplands (>50%) Swamp bushland and grassland !. Kidal Km Croplands with open woody vegetation Mosaic Forest / Croplands Map Doc Name: OCHA_RefMap_Draft_v9_111012 Irrigated croplands Submontane forest (900 -1500 m) Creation Date: 12 October 2011 Updated: -

Evaluation Hydrologique De L'afrique Sub-Saharienne. Pays De L

Banque Mondiale Programme des Nations Unies pour le Développement Banque Africaine de Développement Ministère Français de la Coopération Evaluation Hydrologique de l'Afrique Sub-Saharienne Pays de l'Afrique de l'Ouest Rapport de pays: MALI Juillet 1992 Mott MacDonald BCEOM SOGREAH ORSTOM International Montpellier Grenoble Montpellier Cambridge,UK France France France PREAMBULE Celte étude constitue la troisième tranche de l'évaluation hydrologique régionale de l'Afrique Sub-Saharienne financée par le PNUD (Projet RAF/87/030), la Banque Africaine de Développement, et le Fonds d'Aide et de Coopération de la République Française. L'Etude a porté sur 23 pays de l'Afrique de l'Ouest et a débuté en Septembre 1990. Les pays furent visités par les membres de l'équipe d'étude entre Novembre 1990 et Novembre 1991. Le temps global consacré à chaque pays a été de six semaines en moyenne, dont la moitié au bureau des consultants. Dans 17 pays, ces derniers ont été introduits par le CIEH. L'étude a été organisée de manière à ce que les évaluations soient réalisées par le personnel de MOIT MacDonald International, du BCEOM, de SOGREAH, de l'ORSTOM et de plusieurs consultants nationaux. Dès le début, une attention particulière a été portée à la cohérence de l'approche et à l'homogénéité de l'évaluation. Le projet consistait à évaluer l'état des systèmes de collecte de données hydrologiques existants, et à formuler des recommandations nécessaires à leur amélioration, de manière à assister les pays dans l'établissement ou l'amélioration de bases de données hydrologiques fiables en vue de leur permettre une meilleure planification des programmes et projets de d'aménagement des ressources en eaux superficielles et souterraines. -

1. KAYES : 2. KOULIKORO District De Kolokani District De Koulikoro

MINISTERE DE LA SANTE REPUBLIQUE DU MALI ET DE L’HYGIENE PUBLIQUE UN PEUPLE UN BUT UNE FOI SECRETARIAT GENERAL RAPPORT JOURNALIER DE LA GESTION DE L’EPIDEMIE DE MENINGITE AU MALI JOURNEE DU 18 MARS 2016 1. KAYES : La situation épidémiologique est de 0 cas et 0 décès. 2. KOULIKORO District de Kolokani Nombre de cas présumé : 2 Nombre de décès : 0 Village de Guiyogo, aire de santé de Guiyoyo, district de Koulokani, 4 ans Village de Guidiou, aire de santé Guidiou, 4 ans, sexe féminin, 58 ans Les prélèvements de LCR ont été effectués et envoyés à l’INRSP de Bamako District de Koulikoro Nombre de cas présumé : 2 Nombre de décès : 0 Quartier Souban, aire de santé du CSCOM Central, district de Koulikoro, sexe féminin, 11 mois et sexe masculin, 4ans, Les prélèvements de LCR ont été effectués et envoyés à l’INRSP de Bamako District de Ouéléssébougou Nombre de cas présumé : 0 cas Nombre de décès : 0 ; Nombre de personnes hospitalisées en traitement : 3 Actions en cours : - Poursuite de la surveillance active et de la prise en charge des cas ; - Poursuite des activités d’information, de sensibilisation et de communication sur les radios locales, médias nationaux, médias sociaux et électroniques ; - Tenue de la réunion du Comité de gestion des épidémies et catastrophes au cabinet du MSHP. 3. SIKASSO La situation épidémiologique est de 0 cas et 0 décès. 4. SEGOU : La situation épidémiologique est de 0 cas et 0 décès. 5. MOPTI : La situation épidémiologique est de 0 cas et 0 décès. 6. TOMBOUCTOU : La situation épidémiologique est de 0 cas et 0 décès. -

340102-Fre.Pdf (433.2Kb)

r 1 RAPPORT DE MISSION [-a mission que nous venons de terminer avait pour but de mener une enquête dans quelques localités du Mali pour avoir une idée sur la vente éventuelle de I'ivermectine au Mali et le suivi de la distribution du médicament par les acteurs sur le terrain. En effet sur ordre de mission No 26/OCPlZone Ouest du3l/01196 avec le véhicule NU 61 40874 nous avons debuté un périple dans les régions de Koulikoro, Ségou et Sikasso et le district de Bamako, en vue de vérifier la vente de l'ivermectine dans les pharmacies, les dépôts de médicament ou avec les marchands ambulants de médicaments. Durant notre périple, nous avons visité : 3 Régions : Koulikoro, Ségou, Sikasso 1 District : Bamako 17 Cercles Koulikoro (06 Cercles), Ségou (05 Cercles), Sikasso (06 Cercles). 1. Koulikoro l. Baraouli 1. Koutiala 2. Kati 2. Ségou 2. Sikasso 3. Kolokani 3. Macina 3. Kadiolo 4. Banamba 4. Niono 4. Bougouni 5. Kangaba 5. Bla 5. Yanfolila 6. Dioila 6. Kolondiéba avec environ Il4 pharmacies et dépôts de médicaments, sans compter les marchands ambulants se trouvant à travers les 40 marchés que nous avons eu à visiter (voir détails en annexe). Malgré notre fouille, nous n'avons pas trouvé un seul comprimé de mectizan en vente ni dans les pharmacies, ni dans les dépôts de produits pharmaceutiques ni avec les marchands ambulants qui ne connaissent d'ailleurs pas le produit. Dans les centres de santé où nous avons cherché à acheter, on nous a fait savoir que ce médicament n'est jamais vendu et qu'il se donne gratuitement à la population. -

FINAL REPORT Quantitative Instrument to Measure Commune

FINAL REPORT Quantitative Instrument to Measure Commune Effectiveness Prepared for United States Agency for International Development (USAID) Mali Mission, Democracy and Governance (DG) Team Prepared by Dr. Lynette Wood, Team Leader Leslie Fox, Senior Democracy and Governance Specialist ARD, Inc. 159 Bank Street, Third Floor Burlington, VT 05401 USA Telephone: (802) 658-3890 FAX: (802) 658-4247 in cooperation with Bakary Doumbia, Survey and Data Management Specialist InfoStat, Bamako, Mali under the USAID Broadening Access and Strengthening Input Market Systems (BASIS) indefinite quantity contract November 2000 Table of Contents ACRONYMS AND ABBREVIATIONS.......................................................................... i EXECUTIVE SUMMARY............................................................................................... ii 1 INDICATORS OF AN EFFECTIVE COMMUNE............................................... 1 1.1 THE DEMOCRATIC GOVERNANCE STRATEGIC OBJECTIVE..............................................1 1.2 THE EFFECTIVE COMMUNE: A DEVELOPMENT HYPOTHESIS..........................................2 1.2.1 The Development Problem: The Sound of One Hand Clapping ............................ 3 1.3 THE STRATEGIC GOAL – THE COMMUNE AS AN EFFECTIVE ARENA OF DEMOCRATIC LOCAL GOVERNANCE ............................................................................4 1.3.1 The Logic Underlying the Strategic Goal........................................................... 4 1.3.2 Illustrative Indicators: Measuring Performance at the -

Policies for Sustainable Mobility and Accessibility in Cities of Mali

Page 1 Policies for sustainable mobility and accessibility in cities of Mali Page 2 ¾ SSATP – Mali - Policies for Sustainable Mobility and Accessibility in Urban Areas – October 2019 Page 3 ¾ SSATP – Mali - Policies for Sustainable Mobility and Accessibility in Urban Areas – October 2019 Policies for sustainable mobility and accessibility in urban areas of Mali An international partnership supported by: Page 4 ¾ SSATP – Mali - Policies for Sustainable Mobility and Accessibility in Urban Areas – October 2019 The SSATP is an international partnership to facilitate policy development and related capacity building in the transport sector in Africa. Sound policies lead to safe, reliable, and cost-effective transport, freeing people to lift themselves out of poverty and helping countries to compete internationally. * * * * * * * The SSATP is a partnership of 42 African countries: Angola, Benin, Burkina Faso, Burundi, Cameroon, Cape Verde, Central African Republic, Chad, Comoros, Congo, Democratic Republic of the Congo, Côte d'Ivoire, Djibouti, Eswatini, Ethiopia, Gabon, The Gambia, Ghana, Guinea, Guinea-Bissau, Kenya, Lesotho, Liberia, Madagascar, Malawi, Mali, Mauritania, Morocco, Mozambique, Namibia, Niger, Nigeria, Rwanda, Senegal, Sierra Leone, South Sudan, Tanzania, Togo, Tunisia, Uganda, Zambia, Zimbabwe; 8 Regional Economic Communities (RECs); 2 African institutions: African Union Commission (AUC) and United Nations Economic Commission for Africa (UNECA); Financing partners for the Third Development Plan: European Commission (main donor), -

GROUPE HUMANITAIRE SECURITE ALIMENTAIRE FOOD SECURITY CLUSTER Bamako/Mali ______

GROUPE HUMANITAIRE SECURITE ALIMENTAIRE FOOD SECURITY CLUSTER Bamako/Mali _______________________________________________________________________________________ SitRep / Contribution to OCHA publication 18 Mai 2012 Responses to the food insecurity due to drought and Conflict crisis: WFP is finishing its first round of targeted food distributions in Kayes, Koulikoro and Mopti regions for an estimated 117,800 beneficiaries. The second round is scheduled to start during the week of 21 May, and WFP might distribute a double ration (two months: May and June) to beneficiaries. CRS first round of food distributions through local purchases in fairs began on Saturday, May 10th, 2012 in the commune of Madiama (Circle of Djenne) and will be extended in other communes of this circle. As of today 3 153 households have received two months food rations (equivalent to $100 per household). Diverse products are been proposed. A total of 140 000 000 FCFA has been invested in that local purchases. Mrs Aminata Sow, Head of Family in Welinngara village received her foods during the ongoing fair in Djenne Logistic support: The second joint mission WFP/UNDSS/OCHA in Mopti will provide further information on the UN common center and logistics hub establishment. North Mali: The WFP commodities on the High Islamic Council convoy have arrived in the three northern cities of Timbuktu, Gao and Kidal. WFP dispatched a total of 31,5mt of mixed commodities (pulses and vegetable oil) to the three regions. This tonnage of mixed WFP commodities complements cereal distributions of the High Islamic Council for provision of a complete food basket to an estimated 7,800 vulnerable conflict-affected people in the North. -

Annuaire Statistique 2015 Du Secteur Développement Rural

MINISTERE DE L’AGRICULTURE REPUBLIQUE DU MALI ----------------- Un Peuple - Un But – Une Foi SECRETARIAT GENERAL ----------------- ----------------- CELLULE DE PLANIFICATION ET DE STATISTIQUE / SECTEUR DEVELOPPEMENT RURAL Annuaire Statistique 2015 du Secteur Développement Rural Juin 2016 1 LISTE DES TABLEAUX Tableau 1 : Répartition de la population par région selon le genre en 2015 ............................................................ 10 Tableau 2 : Population agricole par région selon le genre en 2015 ........................................................................ 10 Tableau 3 : Répartition de la Population agricole selon la situation de résidence par région en 2015 .............. 10 Tableau 4 : Répartition de la population agricole par tranche d'âge et par sexe en 2015 ................................. 11 Tableau 5 : Répartition de la population agricole par tranche d'âge et par Région en 2015 ...................................... 11 Tableau 6 : Population agricole par tranche d'âge et selon la situation de résidence en 2015 ............. 12 Tableau 7 : Pluviométrie décadaire enregistrée par station et par mois en 2015 ..................................................... 15 Tableau 8 : Pluviométrie décadaire enregistrée par station et par mois en 2015 (suite) ................................... 16 Tableau 9 : Pluviométrie enregistrée par mois 2015 ........................................................................................ 17 Tableau 10 : Pluviométrie enregistrée par station en 2015 et sa comparaison à -

THESE Année : 2007-2008 N°/____ / Pour L’Obtention Du Grade De DOCTEUR EN MEDECINE (DIPLÔME D’ETAT)

REPUBLIQUE DU MALI UN PEUPLE - UN BUT - UNE FOI ----------------------- MINISTERE DE L’EDUCATION NATIONALE --------------------- --------------------- FACULTE DE MEDECINE DE PHARMACIE ET D’ODONTO-STOMATOLOGIE --------------------- THESE Année : 2007-2008 N°/____ / Pour l’obtention du grade de DOCTEUR EN MEDECINE (DIPLÔME D’ETAT) NECESSITE ET FAISABILITE DE LA DECENTRALISATION DE LA PRISE EN CHARGE DES MALADES DIABETIQUES A TOUS LES NIVEAUX DE LA PYRAMIDE SANITAIRE AU MALI Présentée et soutenue publiquement le 18/03/2008 Par Devant le jury de la faculté de Médecine, de Pharmacie et D’Odonto-stomatologie de Bamako JURY : Président du jury : Professeur ABDOULAYE AG RHALY Membre du jury : Professeur SAHARE FONGORO Codirecteur : Docteur NAZOUM J. P. DIARRA Directeur de thèse : Professeur SIDIBE ASSA TRAORE Thèse de médecine N. Josiane Sandrine FACULTE DE MEDECINE, DE PHARMACIE ET D’ODONTO-STOMATOLOGIE ANNEE UNIVERSITAIRE 2007-2008 ADMINISTRATION : DOYEN : ANATOLE TOUNKARA – PROFESSEUR 1er ASSESSEUR : DRISSA DIALLO – MAITRE DE CONFERENCES 2ème ASSESSEUR : SEKOU SIDIBE – MAITRE DE CONFERENCES SECRETAIRE PRINCIPAL: YENIMEGUE ALBERT DEMBELE – PROFESSEUR ÂGENT COMPTABLE: Madame COULIBALY FATOUMATA TALL - CONTROLEUR DES FINANCES LES PROFESSEURS HONORAIRES Mr. Alou BA Ophtalmologie Mr. Bocar SALL Orthopédie Traumatologie Secourisme Mr. Souleymane SANGARE Pneumo-phtisiologie Mr. Yaya FOFANA Hématologie Mr. Mamadou L. TRAORE Chirurgie générale Mr. Balla COULIBALY Pédiatrie Mr. Mamadou DEMBELE Chirurgie Générale Mr. Mamadou KOUMARE Pharmacognosie Mr. Ali Nouhoum DIALLO Médecine Interne Mr. Aly GUINDO Gastro-entérologie Mr. Mamadou M. KEITA Pédiatrie Mr. Siné BAYO Anatomie Pathologie- Histoembryologie Mr. Abdoulaye Ag RHALY Médecine Interne Mr. Boulkassoum HAIDARA Législation Mr Boubacar Sidiki CISSE Toxicologie Mr Massa SANOGO Chimie Analytique LISTE DU PERSONNEL ENSEIGNANT PAR D.E.R. -

Appraisal Report Kankan-Kouremale-Bamako Road Multinational Guinea-Mali

AFRICAN DEVELOPMENT FUND ZZZ/PTTR/2000/01 Language: English Original: French APPRAISAL REPORT KANKAN-KOUREMALE-BAMAKO ROAD MULTINATIONAL GUINEA-MALI COUNTRY DEPARTMENT OCDW WEST REGION JANUARY 1999 SCCD : N.G. TABLE OF CONTENTS Page PROJECT INFORMATION BRIEF, EQUIVALENTS, ACRONYMS AND ABBREVIATIONS, LIST OF ANNEXES AND TABLES, BASIC DATA, PROJECT LOGICAL FRAMEWORK, ANALYTICAL SUMMARY i-ix 1 INTRODUCTION.............................................................................................................. 1 1.1 Project Genesis and Background.................................................................................... 1 1.2 Performance of Similar Projects..................................................................................... 2 2 THE TRANSPORT SECTOR ........................................................................................... 3 2.1 The Transport Sector in the Two Countries ................................................................... 3 2.2 Transport Policy, Planning and Coordination ................................................................ 4 2.3 Transport Sector Constraints.......................................................................................... 4 3 THE ROAD SUB-SECTOR .............................................................................................. 5 3.1 The Road Network ......................................................................................................... 5 3.2 The Automobile Fleet and Traffic................................................................................. -

Taoudeni Basin Report

Integrated and Sustainable Management of Shared Aquifer Systems and Basins of the Sahel Region RAF/7/011 TAOUDENI BASIN 2017 INTEGRATED AND SUSTAINABLE MANAGEMENT OF SHARED AQUIFER SYSTEMS AND BASINS OF THE SAHEL REGION EDITORIAL NOTE This is not an official publication of the International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA). The content has not undergone an official review by the IAEA. The views expressed do not necessarily reflect those of the IAEA or its Member States. The use of particular designations of countries or territories does not imply any judgement by the IAEA as to the legal status of such countries or territories, or their authorities and institutions, or of the delimitation of their boundaries. The mention of names of specific companies or products (whether or not indicated as registered) does not imply any intention to infringe proprietary rights, nor should it be construed as an endorsement or recommendation on the part of the IAEA. INTEGRATED AND SUSTAINABLE MANAGEMENT OF SHARED AQUIFER SYSTEMS AND BASINS OF THE SAHEL REGION REPORT OF THE IAEA-SUPPORTED REGIONAL TECHNICAL COOPERATION PROJECT RAF/7/011 TAOUDENI BASIN COUNTERPARTS: Mr Adnane Souffi MOULLA (Algeria) Mr Abdelwaheb SMATI (Algeria) Ms Ratoussian Aline KABORE KOMI (Burkina Faso) Mr Alphonse GALBANE (Burkina Faso) Mr Sidi KONE (Mali) Mr Aly THIAM (Mali) Mr Brahim Labatt HMEYADE (Mauritania) Mr Sidi Haiba BACAR (Mauritania) EXPERT: Mr Jean Denis TAUPIN (France) Reproduced by the IAEA Vienna, Austria, 2017 INTEGRATED AND SUSTAINABLE MANAGEMENT OF SHARED AQUIFER SYSTEMS AND BASINS OF THE SAHEL REGION INTEGRATED AND SUSTAINABLE MANAGEMENT OF SHARED AQUIFER SYSTEMS AND BASINS OF THE SAHEL REGION Table of Contents 1. -

Régions De SEGOU Et MOPTI République Du Mali P! !

Régions de SEGOU et MOPTI République du Mali P! ! Tin Aicha Minkiri Essakane TOMBOUCTOUC! Madiakoye o Carte de la ville de Ségou M'Bouna Bintagoungou Bourem-Inaly Adarmalane Toya ! Aglal Razelma Kel Tachaharte Hangabera Douekiré ! Hel Check Hamed Garbakoira Gargando Dangha Kanèye Kel Mahla P! Doukouria Tinguéréguif Gari Goundam Arham Kondi Kirchamba o Bourem Sidi Amar ! Lerneb ! Tienkour Chichane Ouest ! ! DiréP Berabiché Haib ! ! Peulguelgobe Daka Ali Tonka Tindirma Saréyamou Adiora Daka Salakoira Sonima Banikane ! ! Daka Fifo Tondidarou Ouro ! ! Foulanes NiafounkoéP! Tingoura ! Soumpi Bambara-Maoude Kel Hassia Saraferé Gossi ! Koumaïra ! Kanioumé Dianké ! Leré Ikawalatenes Kormou © OpenStreetMap (and) contributors, CC-BY-SA N'Gorkou N'Gouma Inadiatafane Sah ! ! Iforgas Mohamed MAURITANIE Diabata Ambiri-Habe ! Akotaf Oska Gathi-Loumo ! ! Agawelene ! ! ! ! Nourani Oullad Mellouk Guirel Boua Moussoulé ! Mame-Yadass ! Korientzé Samanko ! Fraction Lalladji P! Guidio-Saré Youwarou ! Diona ! N'Daki Tanal Gueneibé Nampala Hombori ! ! Sendegué Zoumané Banguita Kikara o ! ! Diaweli Dogo Kérengo ! P! ! Sabary Boré Nokara ! Deberé Dallah Boulel Boni Kérena Dialloubé Pétaka ! ! Rekerkaye DouentzaP! o Boumboum ! Borko Semmi Konna Togueré-Coumbé ! Dogani-Beré Dagabory ! Dianwely-Maoundé ! ! Boudjiguiré Tongo-Tongo ! Djoundjileré ! Akor ! Dioura Diamabacourou Dionki Boundou-Herou Mabrouck Kebé ! Kargue Dogofryba K12 Sokora Deh Sokolo Damada Berdosso Sampara Kendé ! Diabaly Kendié Mondoro-Habe Kobou Sougui Manaco Deguéré Guiré ! ! Kadial ! Diondori