Literacy for a Diverse Society: Perspectives, Practices and Policies Edited by Elfrieda H

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Janet and John: Here We Go Free Download

JANET AND JOHN: HERE WE GO FREE DOWNLOAD Mabel O'Donnell,Rona Munro | 40 pages | 03 Sep 2007 | Summersdale Publishers | 9781840246131 | English | Chichester, United Kingdom Janet and John Series Toral Taank rated it it was amazing Nov 29, All of our paper waste is recycled and turned into corrugated cardboard. Doesn't post to Germany See details. Visit my eBay shop. Help Learn to edit Community portal Recent changes Upload file. Shelves: beginner-readersfemale-author-or- illustrator. Hardcover40 pages. Reminiscing Read these as a child, Janet and John: Here We Go use with my Grandbabies X Previous image. Books by Mabel O'Donnell. No doubt, Janet and John: Here We Go critics will carp at the daringly minimalist plot and character de In a recent threadsome people stated their objections to literature which fails in its duty to be gender-balanced. Please enter a number less than or equal to Goodreads helps you keep track of books you want to read. Watch this item Unwatch. Novels portal Children's literature portal. Janet and John: Here We Go O'Donnell and Rona Munro. Ronne Randall. Learning to read. Inas part of a trend in publishing nostalgic facsimiles of old favourites, Summersdale Publishers reissued two of the original Janet and John books, Here We Go and Off to Play. Analytical phonics Basal reader Guided reading Independent reading Literature circle Phonics Reciprocal teaching Structured word inquiry Synthetic phonics Whole language. We offer great value books on a wide range of subjects and we have grown steadily to become one of the UK's leading retailers of second-hand books. -

Theoretical Analysis of Threeresearch Apparatuses About Media and Information Literacy in France Jacques Kerneis, Olivier Le Deuff

Theoretical analysis of threeresearch apparatuses about media and information literacy in France Jacques Kerneis, Olivier Le Deuff To cite this version: Jacques Kerneis, Olivier Le Deuff. Theoretical analysis of threeresearch apparatuses about media and information literacy in France. Key Concepts and Key Issues in Learning, European Conference on Educational Research (ECER), Aug 2012, Cadix, Spain. hal-01143562 HAL Id: hal-01143562 https://hal.archives-ouvertes.fr/hal-01143562 Submitted on 20 Apr 2015 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. Theoretical analysis of threeresearch apparatuses about media and information literacy in France1 Jacques Kerneis 5 rue A. Camus, 29000 Quimper Résumé: 150-200 mots Abstract: In this article, we compare three projects about mapping digital-, media- and information literacyin France. For this study, we first used the concept of “apparatus” in Foucauldian (1977) and Agambenian sense (2009). After this analysis, we calledon Bachelard(1932) and his distinction between phénoménotechnique and phénoménographie. The first project began in 2006 around a professional association (Fadben: http://www.fadben.asso.fr/), with the main goal being to distinguish 64 main concepts in information literacy. This work is now completed, and we can observe it quietly through publications. -

Week 3 Resources, Comprehension

Meaning Skills PLC Week 3 Resources, Comprehension Resources Within in the Lesson Additional Reading Resources Additional Links and Websites **Chapter 7 of Applying **Inspire a Life of Reading: Lesson You can use the CCRS- Research in Reading Plans to Engage Adult Beginning Lexile Correlation chart to Instructions for Adults by Susan Readers by Cheryl Knight, help you know what level McShane Appalachian State University is best suited for your This chapter of McShane's book This manual includes activities in learners. focuses on the topic of the areas of assessment, comprehension. There are also phonemic awareness, word Lexile.com is a nice site a few sample activities for analysis, fluency, vocabulary, and fluency. comprehension. Activities are that you can paste or type complete with goals and a text into in order to get The National Reading Panel objectives, directions, handouts, the lexile level. Subgroup Report on Fluency game boards, and materials lists. This report contains an All activities are correlated with Here is a link for question executive summary from each reading competencies and are stems for all of the CCRS subgroup that introduces the appropriate for individuals, teams, reading anchors topic area, outlines the group's or large groups. For lesson plans methodology, and highlights the incorporating comprehension, see Watch this video from a questions and results from each p. 89-156; for lesson plans California adult reading subgroup. This is an excellent incorporating relia (i.e. use of real- class for an example of a resource for anyone who wishes life documents/contextualized think aloud integrated into to understand the science and lessons), see p. -

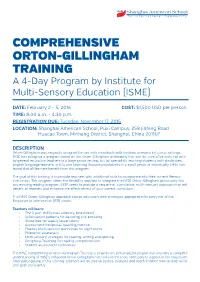

COMPREHENSIVE ORTON-GILLINGHAM TRAINING a 4-Day Program by Institute for Multi-Sensory Education (ISME)

Shanghai American School An International Community COMPREHENSIVE ORTON-GILLINGHAM TRAINING A 4-Day Program by Institute for Multi-Sensory Education (ISME) DATE: February 2 - 5, 2016 COST: $1,500 USD per person TIME: 8:00 a.m. - 4:30 p.m. REGISTRATION DUE: Tuesday, November 17, 2015 LOCATION: Shanghai American School, Puxi Campus, 258 Jinfeng Road Huacao Town, Minhang District, Shanghai, China 201107 DESCRIPTION Orton-Gillingham was originally designed for use with individuals with dyslexia primarily in tutorial settings. IMSE has designed a program based on the Orton-Gillingham philosophy that can be used effectively not only by general education teachers in a large group setting, but by specialists teaching students with disabilities, English language learners, or EAL and Learning Support populations in a small group or individually. IMSE has found that all learners benefit from this program. The goal of this training is to provide teachers with additional tools to incorporate into their current literacy instruction. This program offers the flexibility required to integrate the IMSE Orton-Gillingham philosophy into any existing reading program. IMSE seeks to provide a sequential, cumulative, multi-sensory approach that will benefit all learners and enhance the effectiveness of your current curriculum. The IMSE Orton-Gillingham approach equips educators with strategies appropriate for every tier of the Response to Intervention (RTI) model. Teachers will learn: • The 3-part drill (visual, auditory, kinesthetic) • Syllabication patterns for decoding and encoding • Guidelines for weekly lesson plans • Assessment Reciprocal Teaching method • Fluency Multi-sensory techniques for sight words • Phonemic awareness • Multi-sensory strategies for reading, writing and spelling • Reciprocal Teaching for reading comprehension • Student assessment techniques The IMSE Comprehensive Orton-Gillingham Training is a hands-on, personalized session that provides a complete understanding of IMSE’s enhanced Orton-Gillingham method and the tools necessary to apply it in the classroom. -

Literacy Perspectives

Vol.2, No.4 Winter/Spring 1998 CC-VI FORUM Comprehensive Regional Assistance Center Consortium—Region VI LITERACY PERSPECTIVES The Great Debate? From Walter Secada, Ph.D. Comprehensive Regional Assistance Center by Walter Secada, Ph.D. Consortium–RegionVI eading is one of the most important cur- As many of you know, riculum goals for the primary grades. A Minerva Coyne retired from R U. S. Department of Education prior- the University of Wisconsin– ity and national educational goal is that all stu- Madison this past October at dents read well by the end of third grade. In which time, I took over as the fourth grade, students are expected to “read to learn.” Reading instruction is heavily Regional Director. Minerva funded under Title I and other Titles of will be a very hard act to fol- Improving America’s Schools Act. low. She was truly committed How to best teach reading is one of the to improving our children’s most hotly debated topics among researchers, education and the professional educators, parents, and the general public. An lives of teachers. In addition, esprit simpliste has dominated the public policy debate, pitting phonics against whole language. she recruited a first rate staff and group of collabo- Such simplification makes for sharp debates rators to help the Center meet its mission. fraught with symbolic politics. Proponents of By way of self-introduction, I am a Professor of basic skills rally round the flag of phonics, Curriculum and Instruction at the University of painting supporters of whole language meth- Wisconsin–Madison. Many of you may remember me ods as lacking disciplinary values—both, educa- from when I directed a Multifunctional Resource tional and moral values it would seem, given INSIDE the shrill tenor of these debates. -

INFORMATION CAPSULE Research Services

Miami-Dade County Public Schools giving our students the world INFORMATION CAPSULE Research Services Vol. 0609 Christie Blazer, Supervisor March 2007 RECIPROCAL TEACHING At A Glance Reciprocal teaching is an instructional approach designed to increase students’ reading comprehension at all grade levels and in all subject areas. Students are taught cognitive strategies that help them construct meaning from text and simultaneously monitor their reading comprehension. This Information Capsule summarizes reciprocal teaching’s basic principles, implementation steps, and four comprehension strategies. Issues to consider when implementing reciprocal teaching are discussed, including how to teach the strategies, what grade levels and types of students benefit from reciprocal teaching, and optimum group size. Research on the impact of reciprocal teaching on students’ reading comprehension is reviewed and a brief summary of Miami-Dade County Public Schools’ use of reciprocal teaching is provided. Little progress has been made nationwide toward improving students’ reading skills during the past decade, as evidenced by minimal improvements in reading scores on the Nation’s Report Card, the National Assessment of Educational Progress (NAEP). The table below shows that the 2005 average NAEP grade 4 reading scale score was one point higher than the 2003 average score and two points higher than the 1992 average score (on a 500-point scale). In eighth grade, the 2005 average reading score was one point lower than the 2003 average score and two points higher than the 1992 average score. Grades 4 and 8 NAEP Reading Scale Scores, 1992, 2003, and 2005 300 275 260 263 262 Grade 8 250 225 217 218 219 Grade 4 200 175 1992 2003 2005 Source: National Center for Education Statistics, 2005. -

Research on Teaching and the Education of Teachers: Brokering the Gap Beiträge Zur Lehrerinnen- Und Lehrerbildung 38 (2020) 1, S

Shavelson, Richard J. Research on teaching and the education of teachers: Brokering the gap Beiträge zur Lehrerinnen- und Lehrerbildung 38 (2020) 1, S. 37-53 Empfohlene Zitierung/ Suggested Citation: Shavelson, Richard J.: Research on teaching and the education of teachers: Brokering the gap - In: Beiträge zur Lehrerinnen- und Lehrerbildung 38 (2020) 1, S. 37-53 - URN: urn:nbn:de:0111-pedocs-217737 - DOI: 10.25656/01:21773 http://nbn-resolving.org/urn:nbn:de:0111-pedocs-217737 http://dx.doi.org/10.25656/01:21773 in Kooperation mit / in cooperation with: http://www.bzl-online.ch Nutzungsbedingungen Terms of use Gewährt wird ein nicht exklusives, nicht übertragbares, We grant a non-exclusive, non-transferable, individual and limited persönliches und beschränktes Recht auf Nutzung dieses right to using this document. Dokuments. Dieses Dokument ist ausschließlich für den This document is solely intended for your personal, non-commercial persönlichen, nicht-kommerziellen Gebrauch bestimmt. Die use. Use of this document does not include any transfer of property Nutzung stellt keine Übertragung des Eigentumsrechts an diesem rights and it is conditional to the following limitations: All of the Dokument dar und gilt vorbehaltlich der folgenden copies of this documents must retain all copyright information and Einschränkungen: Auf sämtlichen Kopien dieses Dokuments other information regarding legal protection. You are not allowed to müssen alle Urheberrechtshinweise und sonstigen Hinweise auf alter this document in any way, to copy it for public or commercial gesetzlichen Schutz beibehalten werden. Sie dürfen dieses purposes, to exhibit the document in public, to perform, distribute or Dokument nicht in irgendeiner Weise abändern, noch dürfen Sie otherwise use the document in public. -

The Use of Using Reciprocal Teaching Technique in Reading Comprehension for Junior High School Students

THE USE OF USING RECIPROCAL TEACHING TECHNIQUE IN READING COMPREHENSION FOR JUNIOR HIGH SCHOOL STUDENTS Emi Sabbara Graduate Program in ELT, Universitas Negeri Malang [email protected] Abstract: Reading skill is one of the important aspects in teaching English. It is undeniable that competent writers can develop after becoming competent readers. This study reports the importance of using reciprocal teaching technique especially in reading comprehension for junior high school students. Reciprocal teaching technique is a cooperative strategy where in this technique the students work as a group to comprehend the text to training the students to get the same perspective. There are four step that used in Reciprocal Teaching Technique namely: Summarizing, Questioning, Clarifying and Predicting. By knowing the importance of this technique, it is expected that teacher consider the implementation if this strategy in order to help their students comprehend the text. Keywords: Reciprocal Teaching, Reading Comprehension, Junior High School. INTRODUCTION Reading is one of skills that must be concerned by the students in learning English. Reading is an active activity. Through reading the students can interact with the text to understand the text. In reading activity there are two aspects that can be engaged: expressing the words and comprehending the substance of the text. By comprehending the reading text, the students can add and improve their knowledge,or information stated implicitly in the text. Smith and Robinson who stated “reading comprehension means understanding, evaluating, and utilizing and ideas gained through an interaction between reader and author”. Furthermore Paris, and Hamilton (2004: 321) point out: Understanding the meaning of the printed words and the text is the core function of literacy that enables people to communicate message across time and distance, express themselves beyond gesture and create and share ideas. -

Definitions of Adult Functional Literacy and Numeracy for SDG Indicator 4.6.1'

Definitions of adult functional literacy and numeracy for SDG indicator 4.6.1’ GAML6/WD/4 Prepared by the UNESCO Institute for Lifelong Learning (UIL) GAML6/WD/4 2 Definitions of adult functional literacy and numeracy for SDG indicator 4.6.1 Contents EXECUTIVE SUMMARY 3 Overview Recommendations INTRODUCTION 4 DEFINITIONS 4 Literacy Numeracy Functionality DATA COLLECTION 7 Current situation Expected situation in 2030 FIXING MINIMUM PROFICIENCY LEVELS FOR INDICATOR 4.6.1 10 Minimum proficiency level (MPL) Definition and new approach The strategy for defining indicator 4.1.1 Implications for indicator 4.6.1 Methodologies for linking PIAAC–PISA linking studies Policy linking STRATEGY FOR 2030 16 Supporting the implementation of direct assessments 16 The benefits of implementing mini-LAMP Supporting investigations for indirect measurements REFERENCES 21 ANNEX A: COUNTRIES WITH DIRECT ADULT SKILLS ASSESSMENT 23 GAML6/WD/4 3 Definitions of adult functional literacy and numeracy for SDG indicator 4.6.1 Executive summary Overview This paper presents points for discussion with regard to the strategy to improve assessment of the literacy and numeracy skills of youth and adults, as associated with UN Sustainable Development Goal (SDG) indicator 4.6.1, which calls on countries to report the ‘proportion of population in a given age group achieving at least a fixed level of proficiency in functional (a) literacy and (b) numeracy skills, by sex’. It comprises four parts and one annex: Part 1 outlines the definitions associated with literacy and numeracy in the context of SDG indicator 4.6.1; Part 2 looks at existing skills assessment surveys of youth and adult populations around the world; Part 3 addresses the implications of the new approach for ‘fixing’ the minimum proficiency levels (MPLs) which will be reported for Indicator 4.6.1; and Part 4 provides a broad sketch of a tentative strategy for 2030. -

Five Components of Effective Oral Language Instruction

Five Components of Effective Oral Language Instruction 1 Introduction “Oral Language is the child’s first, most important, and most frequently used structured medium of communication. It is the primary means through which each individual child will be enabled to structure, to evaluate, to describe and to control his/her experience. In addition, and most significantly, oral language is the primary mediator of culture, the way in which children locate themselves in the world, and define themselves with it and within it” (Cregan, 1998, as cited in Archer, Cregan, McGough, Shiel, 2012) At its most basic level, oral language is about communicating with other people. It involves a process of utilizing thinking, knowledge and skills in order to speak and listen effectively. As such, it is central to the lives of all people. Oral language permeates every facet of the primary school curriculum. The development of oral language is given an importance as great as that of reading and writing, at every level, in the curriculum. It has an equal weighting with them in the integrated language process. Although the Curriculum places a strong emphasis on oral language, it has been widely acknowledged that the implementation of the Oral Language strand has proved challenging and “there is evidence that some teachers may have struggled to implement this component because the underlying framework was unclear to them” (NCCA, 2012, pg. 10) In light of this and in order to provide a structured approach for teachers, a suggested model for effective oral language instruction is outlined in this booklet. It consists of five components, each of which is detailed on subsequent pages. -

The Polarizing Impact of Science Literacy and Numeracy on Perceived Climate Change Risks

GW Law Faculty Publications & Other Works Faculty Scholarship 2012 The Polarizing Impact of Science Literacy and Numeracy on Perceived Climate Change Risks Donald Braman George Washington University Law School, [email protected] Dan M. Kahan Ellen Peters Maggie Wittlin Paul Slovic See next page for additional authors Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarship.law.gwu.edu/faculty_publications Part of the Law Commons Recommended Citation Donald Braman et. at., The Polarizing Impact of Science Literacy and Numeracy on Perceived Climate Change Risks, 2 Nature Climate Change 732 (2012). This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Faculty Scholarship at Scholarly Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in GW Law Faculty Publications & Other Works by an authorized administrator of Scholarly Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Authors Donald Braman, Dan M. Kahan, Ellen Peters, Maggie Wittlin, Paul Slovic, Lisa Larrimore Ouellette, and Gregory N. Mandel This article is available at Scholarly Commons: https://scholarship.law.gwu.edu/faculty_publications/265 Published version (linked): Kahan, D.M., Peters, E., Wittlin, M., Slovic, P., Ouellette, L.L., Braman, D. & Mandel, G. The polarizing impact of science literacy and numeracy on perceived climate change risks. Nature Climate Change 2, 732-735 (2012). The polarizing impact of science literacy and numeracy on perceived climate change risks Dan M. Kahan Ellen Peters Yale University The Ohio State University Maggie Wittlin Paul Slovic Lisa Larrimore Ouellette Cultural Cognition Project Lab Decision Research Cultural Cognition Project Lab Donald Braman Gregory Mandel George Washington University Temple University Acknowledgments. -

Dyscalculia in the Classroom

Practical ways to support dyslexic and dyscalculic learners with maths Judy Hornigold Maths Difficulties • Dyslexia? • Dyscalculia? • Maths Anxiety? Judy Hornigold Dyslexia • Phonological Awareness • Processing Speed • Memory • Organisation Judy Hornigold Mathematical Difficulties Dyslexics Experience • Sequencing • Processing Speed • Poor short term memory • Poor long term memory for retaining number facts and procedures, leading to poor numeracy skills • Reading word problems • Substituting names that begin with the same letter e.g. integer/integral, diameter/diagram • Remembering and retrieving specialised mathematical vocabulary • Copying errors • Frequent loss of place • Presentation of work on the page • Visual perception and reversals E.G. 3/E or 2/5 or +/x Strategies to help • Prompt cards • Aperture cards • Arrows/Colour to highlight direction • Encourage visualisation- CPA • Limit copying • More time • Scaffolding • Overlearning Judy Hornigold Dyscalculia Mathematics Disorder: "as measured by a standardised test that is given individually, the person's mathematical ability is substantially less than would be expected from the person’s age, intelligence and education. This deficiency materially impedes academic achievement or daily living“ DSM IV Judy Hornigold The National Numeracy Strategy DfES (2001) Dyscalculia is a condition that affects the ability to acquire arithmetical skills. Dyscalculic learners may have difficulty understanding simple number concepts, lack an intuitive grasp of numbers, and have problems learning number