Where Have All the Laborers Gone?

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Toying with Twin Peaks: Fans, Artists and Re-Playing of a Cult-Series

CULTURE / RECEPTION / CONSUMPTION TOYING WITH TWIN PEAKS: FANS, ARTISTS AND RE-PLAYING OF A CULT-SERIES KATRIINA HELJAKKA Name Katriina Heljakka and again through mimetic practices such as re-creation of Academic centre School of History, Culture and Arts Studies characters and through photoplay. Earlier studies indicate (Degree Program of) Cultural Production and Landscape that adults are showing increased interest in character toys Studies, University of Turku such as dolls, soft toys (or plush) and action figures and vari- E-mail address [email protected] ous play patterns around them (Heljakka 2013). In this essay, the focus is, on the one hand on industry-created Twin Peaks KEYWORDS merchandise, and on the other hand, fans’ creative cultivation Adult play; fandom; photoplay; re-playing; toy play; toys. and play with the series scenes and its characters. The aim is to shed light on the object practices of fans and artists and ABSTRACT how their creativity manifests in current Twin Peaks fandom. This article explores the playful dimensions of Twin Peaks The essay shows how fans of Twin Peaks have a desire not only (1990-1991) fandom by analyzing adult created toy tributes to influence how toyified versions of e.g. Dale Cooper and the to the cult series. Through a study of fans and artists “toy- Log Lady come to existence, but further, to re-play the series ing” with the characters and story worlds of Twin Peaks, I will by mimicking its narrative with toys. demonstrate how the re-playing of the series happens again 25 SERIES VOLUME I, Nº 2, WINTER 2016: 25-40 DOI 10.6092/issn.2421-454X/6589 INTERNATIONAL JOURNAL OF TV SERIAL NARRATIVES ISSN 2421-454X PARATEXTS, FANDOMS AND THE PERSISTENCE OF TWIN PEAKS CULTURE / RECEPTION / CONSUMPTION > KATRIINA HELJAKKA TOYING WITH TWIN PEAKS: FANS, ARTISTS AND RE-PLAYING OF A CULT-SERIES FIGURE 1. -

Twin Peaks’ New Mode of Storytelling

ARTICLES PROPHETIC VISIONS, QUALITY SERIALS: TWIN PEAKS’ NEW MODE OF STORYTELLING MIKHAIL L. SKOPTSOV ABSTRACT Following the April 1990 debut of Twin Peaks on ABC, the TV’, while disguising instances of authorial manipulation evi- vision - a sequence of images that relates information of the dent within the texts as products of divine internal causality. narrative future or past – has become a staple of numerous As a result, all narrative events, no matter how coincidental or network, basic cable and premium cable serials, including inconsequential, become part of a grand design. Close exam- Buffy the Vampire Slayer(WB) , Battlestar Galactica (SyFy) and ination of Twin Peaks and Carnivàle will demonstrate how the Game of Thrones (HBO). This paper argues that Peaks in effect mode operates, why it is popular among modern storytellers had introduced a mode of storytelling called “visio-narrative,” and how it can elevate a show’s cultural status. which draws on ancient epic poetry by focusing on main char- acters that receive knowledge from enigmatic, god-like figures that control his world. Their visions disrupt linear storytelling, KEYWORDS allowing a series to embrace the formal aspects of the me- dium and create the impression that its disparate episodes Quality television; Carnivale; Twin Peaks; vision; coincidence, constitute a singular whole. This helps them qualify as ‘quality destiny. 39 SERIES VOLUME I, SPRING 2015: 39-50 DOI 10.6092/issn.2421-454X/5113 INTERNATIONAL JOURNAL OF TV SERIAL NARRATIVES ISSN 2421-454X ARTICLES > MIKHAIL L. SKOPTSOV PROPHETIC VISIONS, QUALITY SERIALS: TWIN PEAKS’ NEW MODE OF STORYTELLING By the standards of traditional detective fiction, which ne- herself and possibly The Log Lady, are visionaries as well. -

David Lynch, Twin Peaks Creator, Brings Paintings to Brisbane's GOMA

Bodey, Michael. “David Lynch, Twin Peaks creator, brings paintings to Brisbane’s GOMA.” The Australian. 15 November 2014. Web. David Lynch, Twin Peaks creator, brings paintings to Brisbane’s GOMA Airplane Tower (2013) by David Lynch. Source: Supplied By Michael Bodey THE story seems familiar. An individual, a one-time phenomenon in one field, pulls back from the spotlight to concentrate on their true love: painting. Filmmaker David Lynch, however, is no peripatetic painter. He’s an art school graduate, and as a child he dreamed of a life of painting but thought it an unachievable folly. That was until a mentor showed him it could be otherwise. Lynch was a promising young artist before moving to the screen in such an indelible fashion, creating off-kilter films and the seminal television series Twin Peaks, which will return next year reimagined 25 years after the crime. And while the world in 2015 will be waiting to see what exactly the auteur does with that famous series, Lynch will have his artistic focus set, at least briefly, on Australia. In March, Lynch will make his first visit to these shores when Brisbane’s Gallery of Modern Art presents one of the largest surveys of his work, a retrospective of the American’s paintings, sculptures and films. The exclusive show of some 200 works, entitled David Lynch: Between Two Worlds and curated by QAGOMA’s Jose Da Silva, continues a late-career renaissance for a man better known for the breathtaking and singularly distinct cinema and television style that marked the 1980s and 90s, beginning with Eraserhead in 1977 through to Mulholland Drive 24 years later. -

Twin Peaks 101: Pilot 1990

TWIN PEAKS #001 Written by Mark Frost and David Lynch Based on, If Any First Draft JULY 12, 1989 Revisions: August 10, 1989 - Blue August 18, 1989 - Pink ACT ONE FADE IN: 1. EXT. GREAT NORTHERN HOTEL - DAY 1. Dawn breaks over the Great Northern. CUT TO: 2. INT. GREAT NORTHERN HOTEL ROOM - DAY 2. We hear him before we see him, but DALE COOPER is perched six inches above the floor in a one-handed yoga "frog" position, wearing boxer shorts and a pair of socks, talking into the tape recorder which is sitting on the carpet near his head. COOPER Diane ... 6:18 a.m., room 315, Great Northern Hotel up here in Twin Peaks. Slept pretty well. Non- smoking room. No tobacco smell. That's a nice consideration for the business traveller. A hint of douglas fir needles in the air. As Sheriff Truman indicated they would, everything this hotel promised, they've delivered: clean, reasonably priced accomodations ... telephone works ... bathroom in really tip-top shape ... no drips, plenty of hot water with good, steady pressure ... could be a side- benefit of the waterfall just outside my window ... firm mattress, but not too firm ... and no lumps like that time I told you about down in El Paso ... Diane, what a nightmare that was, but of course you've heard me tell that story once or twice before. Haven't tried the television. Looks like cable, probably no reception problems. But the true test of any hotel, as you know, is that morning cup of coffee, which I'll be getting back to you about within the half hour .. -

LOST Fandom and Everyday Philosophy

"Accidental Intellectuals": LOST Fandom and Everyday Philosophy Author: Abigail Letak Persistent link: http://hdl.handle.net/2345/2615 This work is posted on eScholarship@BC, Boston College University Libraries. Boston College Electronic Thesis or Dissertation, 2012 Copyright is held by the author, with all rights reserved, unless otherwise noted. ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! This thesis is dedicated to everyone who has ever been obsessed with a television show. Everyone who knows that adrenaline rush you get when you just can’t stop watching. Here’s to finding yourself laughing and crying along with the characters. But most importantly, here’s to shows that give us a break from the day-to-day milieu and allow us to think about the profound, important questions of life. May many shows give us this opportunity as Lost has. Acknowledgements First and foremost I would like to thank my parents, Steve and Jody, for their love and support as I pursued my area of interest. Without them, I would not find myself where I am now. I would like to thank my advisor, Juliet Schor, for her immense help and patience as I embarked on combining my personal interests with my academic pursuits. Her guidance in methodology, searching the literature, and general theory proved invaluable to the completion of my project. I would like to thank everyone else who has provided support for me throughout the process of this project—my friends, my professors, and the Presidential Scholars Program. I’d like to thank Professor Susan Michalczyk for her unending support and for believing in me even before I embarked on my four years at Boston College, and for being the one to initially point me in the direction of sociology. -

How Twin Peaks Changed the Face of Contemporary Television

“That Show You Like Might Be Coming Back in Style” 44 DOI: 10.1515/abcsj-2015-0003 “That Show You Like Might Be Coming Back in Style”: How Twin Peaks Changed the Face of Contemporary Television RALUCA MOLDOVAN Babeş-Bolyai University, Cluj-Napoca Abstract The present study revisits one of American television’s most famous and influential shows, Twin Peaks, which ran on ABC between 1990 and 1991. Its unique visual style, its haunting music, the idiosyncratic characters and the mix of mythical and supernatural elements made it the most talked-about TV series of the 1990s and generated numerous parodies and imitations. Twin Peaks was the brainchild of America’s probably least mainstream director, David Lynch, and Mark Frost, who was known to television audiences as one of the scriptwriters of the highly popular detective series Hill Street Blues. When Twin Peaks ended in 1991, the show’s severely diminished audience were left with one of most puzzling cliffhangers ever seen on television, but the announcement made by Lynch and Frost in October 2014, that the show would return with nine fresh episodes premiering on Showtime in 2016, quickly went viral and revived interest in Twin Peaks’ distinctive world. In what follows, I intend to discuss the reasons why Twin Peaks was considered a highly original work, well ahead of its time, and how much the show was indebted to the legacy of classic American film noir; finally, I advance a few speculations about the possible plotlines the series might explore upon its return to the small screen. Keywords: Twin Peaks, television series, film noir, David Lynch Introduction: the Lynchian universe In October 2014, director David Lynch and scriptwriter Mark Frost announced that Twin Peaks, the cult TV series they had created in 1990, would be returning to primetime television for a limited nine episode run 45 “That Show You Like Might Be Coming Back in Style” broadcast by the cable channel Showtime in 2016. -

Twin Peaks at Twenty-Five

IN FOCUS: Returning to the Red Room—Twin Peaks at Twenty-Five Foreword by DAVID LAVERY or Twin Peaks (ABC, 1990–1991), 2015 was a damn fine year. The last annum has seen the completion of a new collection of critical essays ( Jeffrey Weinstock and Catherine Spooner’s Return to “Twin Peaks”: New Approaches to Theory & Genre in Television), an international conference in the United Kingdom (“ ‛I’ll See You Again Fin 25 Years’: The Return of Twin Peaks and Generations of Cult TV” at the University of Salford), and the current In Focus.1 Not coincidently, this has transpired alongside the commissioning of the return of the series on the American premium cable channel Showtime for a 2017 debut. Long before this Twin Peaks renaissance, the place of David Lynch and Mark Frost’s “quirky quality” series in TV history was, however, already secure.2 As the creator of the iconic series Mad Men, Matthew Weiner, now fifty years old, put it definitively: “I was already out of college when Twin Peaks came on, and that was where I became aware of what was possible on television.”3 Twin Peaks has played a central role as well in our understanding of what is possible in television studies. As I have written and spoken about elsewhere, the collection Full of Secrets: Critical Approaches to “Twin 1 See Jeffrey Weinstock and Catherine Spooner, eds., Return to “Twin Peaks”: New Approaches to Materiality, Theory, and Genre on Television (Basingstoke, UK: Palgrave Macmillan, 2015). For a review of the conference, see Ross Garner, “Conference Review: “‘I’ll See You Again in 25 Years’: The Return of Twin Peaks and Generations of Cult TV”: University of Salford, 21–22 May 2015,” Critical Studies in Television Online, June 5, 2015, http://cstonline.tv/twin-peaks. -

Twin Peaks Is Still Majestically Creepy - the Globe and Mail 2016-12-10, 11�15 AM a Visit to the World of Twin Peaks Is Still Majestically Creepy Monday, Apr

A visit to the world of Twin Peaks is still majestically creepy - The Globe and Mail 2016-12-10, 1115 AM A visit to the world of Twin Peaks is still majestically creepy Monday, Apr. 25, 2016 11:57AM EDT Seattle was the capital of the 1990s. A relatively small, out-of-the-way city, it managed to provide some of the most powerful cultural images of the decade: the Starbucks sophistication of Frasier Crane, the heartbreak houseboat of Sleepless in Seattle and – most unforgettable for people my age – the dirty, long hair, flannel and thrift-store sweaters of grunge. Today, as the children of the 1990s grow into the yuppies of the 2010s, Seattle is fast becoming the first city of nineties nostalgia. With some travel cash and vacation days to spare, thirtysomethings such as myself can’t resist the Pacific http://www.theglobeandmail.com/life/travel/destinations/the-majestically-creepy-towns-at-the-heart-of-twinpeaks/article29660457/ Page 1 of 9 A visit to the world of Twin Peaks is still majestically creepy - The Globe and Mail 2016-12-10, 1115 AM Northwest’s promise of recapturing a slice of our youth. The era of Kurt Cobain cruises and Pearl Jam pilgrimages is upon us. Most such trips, alas, are doomed to end in disappointment. The combined force of the twin tech booms of Microsoft and Amazon have turned greater Seattle into one of the fastest-growing regions in the United States. Rapid sprawl and lightning-fast gentrification have mostly wiped 1990s Seattle off the map. Yesterday’s ragged rock club has become today’s Whole Foods. -

1 Ma C H Inal

MACHINAL presents Performance Studies and Dance, School Theatre, of UMD February 18 & 20, 2021 STREAMING 1 SCHOOL OF THEATRE, DANCE, AND PERFORMANCE STUDIES Maura Keefe, Producing Director Machinal THEATRE DANCE By Sophie Treadwell Director ........................................................................................................... Brian MacDevitt Associate Director and Acting Coach ..............................................................Fraser Stevens FEARLESS NEW PLAY FESTIVAL Intimacy Director ............................................................................................. Kendra Portier Jennifer Barclay, festival director Scenic Designer ................................................................................................... Rochele Mac Lauren Yee, keynote playwright Costume Designer ...........................................................................................Madison Booth STREAMING Lighting Designer ...............................................................................................Jacob Hughes NOVEMBER 19-22, 2020 FALL MFA DANCE THESIS CONCERT Projection Designer ............................................................................................. Devin Kinch Video Programs Designer ........................................................... Zavier Augustus Lee Taylor Ghost Bride by Rose Xinran Qi Responsive Wild by Krissy Harris Sound Designer ........................................................................................................... Roc -

Alice's Academy

The Looking Glass : New Perspectives on Children's Literature, Vol 11, No 1 (2007) HOME ABOUT LOG IN REGISTER SEARCH CURRENT ARCHIVES ANNOUNCEMENTS Home > Vol 11, No 1 (2007) > Parsons Font Size: Alice's Academy "That's Classified": Class Politics and Adolescence in Twin Peaks Elizabeth Parsons Elizabeth Parsons lectures in Children's Literature and Literary Studies at Deakin University, Melbourne, Australia. Her current research examining class dynamics in texts for children and young adults is part of a collaborative project with Clare Bradford, led by Elizabeth Bullen. Her research focus also includes the politics of risk society in children's texts and childhood resilience. Airing on the ABC television network and running for two series in the early 1990s, Twin Peaks made playful fodder of all manner of American cultural icons and imperatives. The slow camera pan to a mounted deer head with the slogan "the buck stopped here" flags the comic significance of money, and it is bucks of the greenbacked variety that propel my reading of class politics as inflected by adolescent sexuality in the series. However, class, sex and age are tripartite functions of social location and, as Bourdieu says: "sexual properties are as inseparable from class properties as the yellowness of a lemon is from its acidity: a class is defined in an essential respect by the place and value it gives to the two sexes...". He continues, "the true nature of a class or class fraction is expressed in its distribution by sex or age (qtd. in Lovell 20). These sociocultural dynamics motivate my assessment of Twin Peaks and prevent the simpler concept of economic bucks from deflecting attention from the implications of age and gender in social mobility and the accrual of capital. -

'Getting to Know You': Engagement and Relationship Building

See discussions, stats, and author profiles for this publication at: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/242487315 'Getting to Know You': Engagement and Relationship Building Technical Report · January 2005 CITATION READS 1 56 10 authors, including: Davies Banda Bob Muir The University of Edinburgh Leeds Beckett University 21 PUBLICATIONS 71 CITATIONS 10 PUBLICATIONS 73 CITATIONS SEE PROFILE SEE PROFILE Donna Woodhouse Sheffield Hallam University 30 PUBLICATIONS 14 CITATIONS SEE PROFILE Some of the authors of this publication are also working on these related projects: GIPCAP View project National Evaluation of Positive Futures Programme - UK View project All content following this page was uploaded by Davies Banda on 26 May 2015. The user has requested enhancement of the downloaded file. ‘Getting to Know You’: Engagement and Relationship Building First Interim National Positive Futures Case Study Research Report Tim Crabbe Research Team: Davies Banda, Tony Blackshaw, Adam Brown, Clare Choak, Tim Crabbe, Ben Gidley, Gavin Mellor, Bob Muir, Kath O’Connor, Imogen Slater, Donna Woodhouse June 2005 Contents Page ‘Getting to Know You’: Executive Summary 3 Part One: Introduction and Methodology 12 1.1 Preface 12 1.2 The Projects 15 1.3 Methodology 21 Part Two: Starting Blocks: Baselines and Background 31 2.1 From mills and ginnels to suits and vindaloos: The Yorkshire case studies 31 2.2 From docklands to parklands: The Merseyside case studies 48 2.3 From the Costermongers to So Solid: The South London case studies 57 2.4 Community, belonging -

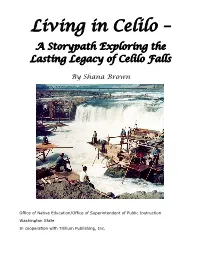

A Storypath Exploring the Lasting Legacy of Celilo Falls

Living in Celilo – A Storypath Exploring the Lasting Legacy of Celilo Falls By Shana Brown Office of Native Education/Office of Superintendent of Public Instruction Washington State In cooperation with Trillium Publishing, Inc. Acknowledgements Shana Brown would like to thank: Carol Craig, Yakama Elder, writer, and historian, for her photos of Celilo as well as her expertise and her children’s story, “I Wish I Had Seen the Falls.” Chucky is really her first grandson (and my cousin). The Columbia River Inter-tribal Fish Commission for providing information about their organization and granting permission to use articles, including a piece from their magazine, Wana Chinook Tymoo. HistoryLink.org for granting permission to use the article, “Dorothea Nordstrand Recalls Old Celilo Falls.” The Northwest Power and Conservation Council for granting permission to use an excerpt from the article, “Celilo Falls.” Ritchie Graves, Chief of the NW Region Hydropower Division’s FCRPS Branch, NOAA Fisheries, for providing information on survival rates of salmon through the dams on the Columbia River system. Sally Thompson, PhD., for granting permission to use her articles. Se-Ah-Dom Edmo, Shoshone-Bannock/Nez Perce/Yakama, Coordinator of the Indigenous Ways of Knowing Program at Lewis and Clark College, Columbia River Board Member, and Vice- President of the Oregon Indian Education Association, for providing invaluable feedback and guidance as well as copies of the actual notes and letters from the Celilo Falls Community Club. The Oregon Historical Society for granting permission to use articles from the Oregon Historical Quarterly. The Oregon Historical Society Research Library Moving Image Collections for granting permission to use video material.