Navigation House First Floor Plan

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Beginner's Guide to Boating on Inland Waterways

Ti r A Beginner’s Guide To Boating On Inland Waterways Take to the water with British Waterways and the National Rivers Authority With well over 4,000 km (2,500 miles) of rivers and canals to explore, from the south west of England up to Scotland, our inland waterways offer plenty of variety for both the casual boater and the dedicated enthusiast. If you have ever experienced the pleasures of 'messing about on boats', you will know what a wealth of scenery and heritage inland waterways open up to us, and the unique perspective they provide. Boating is fun and easy. This pack is designed to help you get afloat if you are thinking about buying a boat. Amongst other useful information, it includes details of: Navigation Authorities British Waterways (BW) and the National Rivers Authority (NRA), which is to become part of the new Environment Agency for England and Wales on 1 April 1996, manage most of our navigable rivers and canals. We are responsible for maintaining the waterways and locks, providing services for boaters and we licence and manage boats. There are more than 20 smaller navigation authorities across the country. We have included information on some of these smaller organisations. Licences and Moorings We tell you everything you need to know from, how to apply for a licence to how to find a permanent mooring or simply a place for «* ^ V.’j provide some useful hints on buying a boat, includi r, ...V; 'r 1 builders, loans, insurance and the Boat Safety Sch:: EKVIRONMENT AGENCY Useful addresses A detailed list of useful organisations and contacts :: : n a t io n a l libra ry'& ■ suggested some books we think will help you get t information service Happy boating! s o u t h e r n r e g i o n Guildbourne House, Chatsworth Road, W orthing, West Sussex BN 11 1LD ENVIRONMENT AGENCY 1 Owning a Boat Buying a Boat With such a vast.range of boats available to suit every price range, . -

INLAND NAVIGATION AUTHORITIES the Following Authorities Are Responsible for Major Inland Waterways Not Under British Waterways Jurisdiction

INLAND NAVIGATION AUTHORITIES The following authorities are responsible for major inland waterways not under British Waterways jurisdiction: RIVER ANCHOLME BRIDGEWATER CANAL CHELMER & BLACKWATER NAVIGATION The Environment Agency Manchester Ship Canal Co. Essex Waterways Ltd Anglian Region, Kingfisher House Peel Dome, Trafford Centre, Island House Goldhay Way, Orton Manchester M17 8PL Moor Road Peterborough PE2 5ZR T 0161 629 8266 Chesham T 08708 506 506 www.shipcanal.co.uk HP5 1WA www.environment-agency.gov.uk T: 01494 783453 BROADS (NORFOLK & SUFFOLK) www.waterways.org.uk/EssexWaterwaysLtd RIVER ARUN Broads Authority (Littlehampton to Arundel) 18 Colgate, Norwich RIVER COLNE Littlehampton Harbour Board Norfolk NR3 1BQ Colchester Borough Council Pier Road, Littlehampton, BN17 5LR T: 01603 610734 Museum Resource Centre T 01903 721215 www.broads-authority.gov.uk 14 Ryegate Road www.littlehampton.org.uk Colchester, CO1 1YG BUDE CANAL T 01206 282471 RIVER AVON (BRISTOL) (Bude to Marhamchurch) www.colchester.gov.uk (Bristol to Hanham Lock) North Cornwall District Council Bristol Port Company North Cornwall District Council, RIVER DEE St Andrew’s House, St Andrew’s Road, Higher Trenant Road, Avonmouth, Bristol BS11 9DQ (Farndon Bridge to Chester Weir) Wadebridge, T 0117 982 0000 Chester County Council PL27 6TW, www.bristolport.co.uk The Forum Tel: 01208 893333 Chester CH1 2HS http://www.ncdc.gov.uk/ RIVER AVON (WARWICKSHIRE) T 01244 324234 (tub boat canals from Marhamchurch) Avon Navigation Trust (Chester Weir to Point of Air) Bude Canal Trust -

Change at Crt Rebranding Responses True Cost of Licence Changes 2

The Magazine of the National Association of Boat Owners Issue 4 July 2018 ALL CHANGE AT CRT REBRANDING RESPONSES TRUE COST OF LICENCE CHANGES 2 The NABO Council Regional Representatives Chair NW Waterways Stella Ridgway Richard Carpenter (details left) The magazine of the National Association of Boat Owners 07904 091931, [email protected] North East, Yorkshire and Humber, Shared Issue 4 July 2018 Co-Vice Chair, NAG (Licensing and Mooring), Ownership Rep. Communications Officer, Moorings Howard Anguish Contents Mark Tizard 01482 669876 0203 4639806, [email protected] [email protected], [email protected] 4 Editorial Co-Vice Chair London Waterways and NAG (Licensing & Mooring) 5 In the Chair Paul Howland David Williams 6 Fly on the wall 07443 635587, [email protected] 07813 496208 , [email protected] 7 Membership Matters: NABO and Treasurer South East GDRP, Middle Level Bill. Helen Hutt Geoff Wood 9 Around the Regions 07968 491118 , [email protected] 10 News: All change at CRT, New Regional 07831 682092, [email protected] Advisory Board Chairs Southern Waterways Legal Affairs and BSS Rep. 12 More problems with cyclists, Mike Rodd Geoffrey Rogerson Tamworth boater's weekend 07831 860199, [email protected] 07768 736593 13 Talking Points: The true costs of CRT NABO News Editor Midlands Waterways licensing changes Peter Fellows Phil Goulding (details left) 14 Letter on re-branding from Richard Parry and the rationale behind it 19 High Street, Bonsall, Derbyshire, DE4 2AS East Midlands Waterways 01629 825267, [email protected] 17 If only the Trust would listen Joan Jamieson Webmaster, NAG (Operations) and BSS Rep. -

Display PDF in Separate

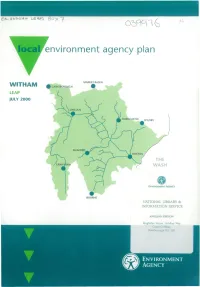

^ / v^/ va/g-uaa/ Ze*PS o b ° P \ n & f+ local environment agency plan WITHAM LEAP JULY 2000 NATIONAL LIBRARY & INFORMATION SERVICE ANGLIAN REGION Kingfisher House, Goldhay Way, Orton Goldhay, ▼ Peterborough PE2 SZR T En v ir o n m e n t Ag e n c y T KEY FACTS AND STATISTICS Total Area: 3,224 km2 Population: 347673 Environment Agency Offices: Anglian Region (Northern Area) Lincolnshire Sub-Office Waterside House, Lincoln Manby Tel: (01522) 513100 Tel: (01507) 328102 County Councils: Lincolnshire, Nottinghamshire, Leicestershire District Councils: West Lindsey, East Lindsey, North Kesteven, South Kesteven, South Holland, Newark & Sherwood Borough Councils: Boston, Melton Unitary Authorities: Rutland Water Utility Companies: Anglian Water Services Ltd, Severn Trent Water Ltd Internal Drainage Boards: Upper Witham, Witham First, Witham Third, Witham Fourth, Black Sluice, Skegness Navigation Authorities: British Waterways (R.Witham) 65.4 km Port of Boston (Witham Haven) 10.6 km Length of Statutory Main River: 633 km Length of Tidal Defences: 22 km Length of Sea Defences: 20 km Length of Coarse Fishery: 374 km Length of Trout Fishery: 34 km Water Quality: Bioloqical Quality Grades 1999 Chemical Qualitv Grades 1999 Grade Length of River (km) Grade Length of River (km) "Very Good" 118.5 "Very Good" 11 "Good" 165.9 "Good" 111.6 "Fairly Good" 106.2 "Fairly Good" 142.8 "Fair" 8.4 "Fair" 83.2 "Poor" 0 "Poor" 50.4 "Bad" 0 "Bad" 0 Major Sewage Treatment Works: Lincoln, North Hykeham, Marston, Anwick, Boston, Sleaford Integrated Pollution Control Authorisation Sites: 14 Sites of Special Scientific Interest: 39 Sites of Nature Conservation Interest: 154 Nature Reserves: 12 Archaeological Sites: 199 Licensed Waste Management Facilities: La n d fill: 30 Metal Recycling Facilities: 16 Storage and Transfer Facilities: 35 Pet Crematoriums: 2 Boreholes: 1 Mobile Plants: 1 Water Resources: Mean Annual Rainfall: 596.7 mm Total Cross Licensed Abstraction: 111,507 ml/yr % Licensed from Groundwater = 32 % % Licensed from Surface Water = 68 % Total Gross Licensed Abstraction: Total no. -

Preliminary Central Lincolnshire Settlement Hierarchy Study Sep 2014

PRELIMINARY CENTRAL LINCOLNSHIRE SETTLEMENT HIERARCHY STUDY September 2014 (Produced to support the Preliminary Draft Central Lincolnshire Local Plan) CONTENTS Page 1. Introduction 1 2. Policy Context 1 3. Methodology 2 4. Central Lincolnshire’s Settlements 2 5. The Settlement Categories 3 6. The Criteria 4 7. Applying the Criteria 6 8. Policy and ‘Localism’ Aspirations 9 9. Next Steps 9 Appendix: Services and Facilities in 10 Central Lincolnshire Settlements 1. Introduction 1.1. A settlement hierarchy ranks settlements according to their size and their range of services and facilities. When coupled with an understanding of the possible capacity for growth, this enables decisions to be taken about the most appropriate planning strategy for each settlement. 1.2. One of the primary aims of establishing a settlement hierarchy is to promote sustainable communities by bringing housing, jobs and services closer together in an attempt to maintain and promote the viability of local facilities and reduce the need to travel to services and facilities elsewhere. A settlement hierarchy policy can help to achieve this by concentrating housing growth in those settlements that already have a range of services (as long as there is capacity for growth), and restricting it in those that do not. 1.3. In general terms, larger settlements that have a higher population and more services and facilities are more sustainable locations for further growth. However, this may not always be the case. A larger settlement may, for example, have physical constraints that cannot be overcome and therefore restrict the scope for further development. Conversely, a smaller settlement may be well located and with few constraints, and suitable for new development on a scale that might be accompanied by the provision of new services and facilities. -

1891 Census Hough on the Hill Parish 1 Road Name

1891 Census Hough on the Hill Parish Road Name First names Relation Age Occupation Born County Notes Hough on the Hill x Lord Alice Elizabeth Head 49 Farmer Frieston Lincs Lord Thomas Son 18 Hough Lincs Lord John Thurlby Son 15 Hough Lincs Lord Mary Mother in law 76 Bucknall Lincs Speed Charlotte Servant 21 Domestic General Servant Carlton On Trent Notts Crow Emma Servant 16 Domestic General Servant Hough Lincs Scofield Frank Servant 16 Farm Servant Denton Lincs Hough Lodge Lord Sarah Ann Head 66 Farmer Sutterton Lincs Lord Edward William Son 37 Hough Lincs Lord Richard Joseph Son 33 Hough Lincs Catlin Richard Servant 61 Farm Servant Marston Lincs Southwood Mary Servant 15 Domestic General Servant Boston Lincs Frieston Corner Hubbard James Head 64 Agricultural Labourer Grantham Lincs Hubbard Patience Wife 66 West Hallam Derbyshire Frieston Road Whaley James Head 65 Agricultural Labourer Hough Lincs Whaley Mary Wife 61 Dunsby Lincs x Cundy William Head 72 Wheelwright Fleet Lincs Cundy Jane Wife 78 Hough Lincs Cundy John Henry Son 38 Hough Lincs Cundy Mary Jane Daughter 30 Hough Lincs Johnson William Grandson 13 x Ireland Carlton Road Newton Edward Head 75 Agricultural Labourer Welby Lincs Newton Mary Ann Wife 65 Old Leak Lincs Dennis Richard Son In Law 27 Agricultural Labourer Thistleton Rutland Dennis Elizabeth Daughter 26 Hough Lincs Carlton Road Bennett William Head 62 Agricultural Labourer Welbourn Lincs Whaley Mary Daughter in law 7 Hough Lincs Stanfield Mary Servant 35 Housekeeper Fulbeck Lincs Carlton Road Daniel John Head 60 Agricultural -

Lincolnshire.. Far 683

TRADES DIRECTORY.] LINCOLNSHIRE.. FAR 683 Darnell William, Bardney, Lincoln Dawson William, Nettleton, Caistor Dickinson Thomas, Friskney, Boston Darnill George, Orby, Boston Dawson Wm. Skeldyke, Kirton, Boston DickinsonW.Sandpits,Westhorpe,Spaldg Darnill Jn. Jack, Grainthorpe, Grimsby Dawson William, Union road, Caistor Dickinson Wm. Westhorpe, Spalding Daubeny Jabez, North Kyme, Lincoln Day Edward Jas. Messingham, Brigg Dickson Frederick, Tumby, Boston Dauber John William, Ruckland, Louth Day John, Wood Enderby, Boston Diggle E. Suttun St. Edmunds, Wisbech Daubney C. Hagworthingham, Spilsby Day John Wm. Scatter, Kirton Lindsey Diggle J.H. Loosegate rd. Moultn.Spldng Dau bney Charles, Leake, Boston Day Ro bt. Scotter Hig hfield, Ki rtonLindsy DiggleJ ohnHarber, j u n. Moulton, Spaldng Daubney Charles, jun. Leake, Boston Day Robert,Scotterthorpe,KirtonLindsy Diggle Thos. Ewerby Thorpe, Sleaford Daubney George, Belchford, Horncastle Day Thomas, Church street, Caistor Diggle Thomas, Weston, Spalding Daubney H.Manor frm.Canwick, Lincoln Day William, Scatter, Kirton Lindsey Dilworth James, Horse Shoe rd.Spaldmg Daubney Henry, Wyberton, Boston Day Wm. Cotehouses, 0 wston Ferry Dimbleby W .BishopNortn. Kirtn.Lindsy Daubney James, Navenby S.O Dean Arthur W. Dowsby, Falkingham Dinnis Thomas, Anderby, Alford Daulton Austin, West Keal, Spilsby Dean Edward, Algarkirk, Boston Dinnison Thomas Hy. Burr la. Spalding Daulton Henry, Bilsby, Alford Dean John, Drayton, Swineshead,Boston Dinsdale John, Nth.Killingholme, Ulceby Daulton Jesse, The Grange, East Keal Dean John, Drove end, Wisbech Dion Frederick, Sibsey, Boston Coates, East Keal, Spilsby Dean John, Goxhill, Hull Dion James, Sibsey, Boston Daulton Joseph, Keal Coates, Spilsby Dean John Chas. Drove end, Wisbech Dion Jesse, Sibsey, Boston Daulton Thomas, East Kirkby, Spilsby Dean John Hy. -

Iwa Submission on the Environment Bill – Appendix A

IWA SUBMISSION ON THE ENVIRONMENT BILL – APPENDIX A IWA VISION FOR SUSTAINABLE PROPULSION ON THE INLAND WATERWAYS EXECUTIVE OVERVIEW 1. Recognising the UK Government’s strategy to reduce emissions from diesel and petrol engines, IWA formed its Sustainable Propulsion Group in 2019 to identify and monitor developments which will enable boats on the inland waterways to fully contribute to the Government’s stated aim of zero CO2 emissions by 2050. 2. The Group has identified a number potential solutions that it recommends should be progressed in order to ensure that boats used on the inland waterways do not get left behind in technological developments. These are outlined in more detail in this paper. 3. To ensure that the inland waterways continue to be sustainable for future generations, and continue to deliver benefits to society and the economy, IWA has concluded that national, devolved and local government should progress the following initiatives: Investment in infrastructure through the installation of 300 shore power mains connection charging sites across the connected inland waterways network. This would improve air quality by reducing the emissions from stoves for heating and engines run for charging batteries, as well as enabling a move towards more boats with electric propulsion. Working with navigation authorities, investment in a national dredging programme across the inland waterways to make propulsion more efficient. This will also have additional environmental benefits on water quality and increasing capacity for flood waters. Research and investment into the production, use and distribution of biofuels. This will be necessary to reduce the environmental impact of existing diesel engines which, given their longevity, will still be around until well after 2050. -

River Slea Including River Slea (Kyme Eau) South Kyme Sleaford

Cruising Map of the River Slea including River Slea (Kyme Eau) South Kyme Sleaford Route 18M3 Map IssueIssue 117 87 Notes 1. The information is believed to be correct at the time of publication but changes are frequently made on the waterways and you should check before relying on this information. 2. We do not update the maps for short term changes such as winter lock closures for maintenance. 3. The information is provides “as is” and the Information Provider excludes all representations, warranties, obligations, and liabilities in relation to the Information to the maximum extent permitted by law. The Information Provider is not liable for any errors or omissions in the Information and shall not be liable for any loss, injury or damage of any kind caused by its use. SSLEALEA 0011 SSLEALEA 0011 This is the September 2021 edition of the map. See www.waterwayroutes.co.uk/updates for updating to the latest monthly issue at a free or discounted price. Contains OS data © Crown copyright and database right. All other work © Waterway Routes. Licensed for personal use only. Business licences on request. ! PPrivaterivate AAccessccess YYouou mmayay wwalkalk tthehe cconnectingonnecting ppathath bbyy kkindind ppermissionermission ooff tthehe llandowners.andowners. PPleaselease rrespectespect ttheirheir pprivacy.rivacy. ! BBridgeridge RRiveriver SSlealea RRestorationestoration PProposedroposed ! PPaperaper MMillill BBridgeridge PPaperaper MMillill LLockock oror LeasinghamLeasingham MillMill LockLock 1.50m1.50m (4'11")(4'11") RRiveriver SSlealea -

History of Lincolnshire Waterways

22 July 2005 The Sleaford Navigation Trust ….. … is a non-profit distributing company limited by guarantee, registered in England and Wales (No 3294818) … has a Registered Office at 10 Chelmer Close, North Hykeham, Lincoln, LN6 8TH … is registered as a Charity (No 1060234) … has a web page: www.sleafordnavigation.co.uk Aims & Objectives of SNT The Trust aims to stimulate public interest and appreciation of the history, structure and beauty of the waterway known as the Slea, or the Sleaford Navigation. It aims to restore, improve, maintain and conserve the waterway in order to make it fully navigable. Furthermore it means to restore associated buildings and structures and to promote the use of the Sleaford Navigation by all appropriate kinds of waterborne traffic. In addition it wishes to promote the use of towpaths and adjoining footpaths for recreational activities. Articles and opinions in this newsletter are those of the authors concerned and do not necessarily reflect SNT policy or the opinion of the Editor. Printed by ‘Westgate Print’ of Sleaford 01529 415050 2 Editorial Welcome Enjoy your reading and I look forward to meeting many of you at the AGM. Nav house at agm Letter from mick handford re tokem Update on token Lots of copy this month so some news carried over until next edition – tokens, nav house description www.river-witham.co.uk Martin Noble Canoeists enjoying a sunny trip along the River Slea below Cogglesford in May Photo supplied by Norman Osborne 3 Chairman’s Report for July 2005 Chris Hayes The first highlight to report is the official opening of Navigation House on June 2nd. -

Publangfordt1969p243.Pdf

The Distribution of Plecoptera and Ephemeroptera in a Lowland Region of Britain (Lincolnshire) by T. E. LANGFORD * & E. S. BRAY** Central Electricity Research Laboratories INTRODUCTION Most of the information concerning distribution and ecology of Plecoptera and Ephemeroptera in Britain, has come from studies of streams in hill and mountain regions, particularly Wales, (HYNES 1961), the English Lake District (See MACAN 1963 p. 20 for refs., GLEDHILL 1960), the Pennines (BROWN, CRAGG & CRISP 1964), Scotland (MORGAN & EGGLISHAW 1965a), and Dartmoor (ELLIOTT 1967). Very little attention has been paid to the distribution of these insects in lowland regions, though isolated records have been published (HARRIS 1952, HYNES 1958, MACAN 1961). From August 1961 to February 1968, regular biological surveys of streams, rivers and pools in Lincolnshire were carried out, mainly to investigate the natural distribution of invertebrate animals and to assess the effects of polluting discharges on the composition of the invertebrate communities. In these surveys 7 species of Plecoptera (Langford 1964), and 15 species of Ephemeroptera (LANGFORD 1965) were recorded. Of these 22 species, 19 were new records for the region . This paper describes the distribution and abundance of the species in relation to the topography and chemistry of Lincolnshire streams, rivers and pools, and the Plecoptera and Ephemeroptera faunas of the *Central Electricity Research Laboratories, Leatherhead, (Surrey) . **Cornwall River Authority Launceston, Cornwall . Received October 22th, 1968. 243 region are compared to those of the mountain regions . The topo- graphy and geology of Lincolnshire is described briefly . This paper is the first of a series dealing with the aquatic macro-invertebrate fauna of the region . -

Newssummer 2016

WILD TROUT TRUST SUMMER 2016 New s ANNUAL DRAW 2016 To be drawn at 7pm, Tuesday 13 December 2016 at The Thomas Lord, West Meon, Hants. Tickets are available via the enclosed order form or by visiting www.wildtrout.org. FIRST PRIZE Kindly donated by Sage, worth £749. A Sage One 8ft 6in, 4-piece, 4-weight Fly Rod. SECOND PRIZE Kindly donated by William Daniel and Famous Fishing, worth £460 . A day’s fishing for 3 rods on 1½ miles of the Lambourn at Weston, Monday to Thursday, before 15 July 2017. THIRD PRIZE Kindly donated by The Peacock at Rowsley and Haddon Fisheries, worth £400. One night’s accommodation in a large double/twin room for two people with three course dinner and buffet breakfast, plus two low-season tickets to fish the Derbyshire Wye. FOURTH PRIZE Kindly donated by Paul Kenyon Esq, worth £100 . WILD TROUT TRUST’S Wine Society six-bottle case . FIFTH PRIZE ANNUAL GET-TOGETHER Kindly donated by Phoenix Lines worth £35. ON THE WYLYE STARTS A Phoenix Furled Tenkara line, plus two Phoenix Furled leaders. ON PAGE TWO NEWSLETTER AUCTION – £72,000! LOST enise Ashton reports on another as possible as buyers, donors or MEMBERS successful WTT annual auction. publicists. The catalogue of lots reflects DThe annual fundraising auction, held the huge range of trout fishing available, e have lost touch with the in March 2016, was again a tremendous as well as the breadth of our support- following members as they success, raising just over £72,000. Our base across the UK and Ireland.