An Analysis of Singapore's Market-Based Tools for Energy

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

SINGAPORE a Living Lab for Renewable Energy

CHAPTER 11 SINGAPORE A Living Lab for Renewable Energy Daren Tang, Intellectual Property Office of Singapore From launching the world’s largest floating photovoltaic (PV) Against this backdrop, it has become imperative for policy test bed to building the first industrial micro-grid test system makers to be kept abreast of the emerging technology in South East Asia,1 Singapore is demonstrating that it can trends in RE to make better-informed decisions about their be a ‘Living Lab’ for renewable energy (RE) innovators to test energy needs. ideas. Beyond testing, innovators can leverage Singapore’s world-class legal framework, robust intellectual property In this chapter, the Intellectual Property Office of Singapore (IP) regime, conducive business environment, and extensive (IPOS) provides some useful insights for decision makers global networks to commercialize their innovative RE ideas, by examining global trends and emerging areas, as well as transforming them into viable technologies for global leading countries in the field of PV, through the lens of a markets. patent landscape analysis. It then discusses, using Singapore as an example, how small nations can play an outsized By 2040, the world’s energy demand is expected to grow role in driving RE innovation, and how IP and IP offices can substantially—by 30%.2 Coupled with the megatrend of rapid complete the innovation value chain to bring technology to urbanization and the ever-increasing appetite for energy, the market. pursuit of RE innovation is more pressing than ever before. The year 2015 marked a milestone: global RE capacity additions exceeded those of fossil fuels and nuclear energy Renewable energy–related patent for the first time.3 Nearly two-thirds of all new net power capacity additions came from renewables in 2016.4 The landscape insights confluence of these factors fuelled the global economy’s The rising interest in RE as an alternative energy source increased investments in RE technologies. -

Press Release

PRESS RELEASE MTI APPOINTS MS CHONG SIAK CHING AS DEPUTY CHAIRMAN, SPRING, AND NEW MEMBERS TO THE EMA AND SPRING BOARDS The Minister for Trade and Industry has appointed Ms Chong Siak Ching as Deputy Chairman of SPRING Singapore, the enterprise development agency. In addition, six new Board members have been appointed to SPRING and one new Board member to the Energy Market Authority (EMA). Their appointments are with effect from 1 April 2008. Ms Chong Siak Ching 2. Ms Chong has vast experience in working with companies, including SMEs. She is heading Ascendas, a leading provider of business space with a presence in 10 countries across Asia. Prior to joining Ascendas, Ms Chong was the Deputy Chief Executive Officer of Jurong Town Corporation. 3. In January 2004, Ms Chong was appointed as one of Singapore’s three representatives to the APEC Business Advisory Council. She is also a Director on the Singapore Tourism Board and the Singapore-India Partnership Foundation. New appointments 4. The following are appointed to the SPRING Singapore and EMA Boards : SPRING Singapore • Mr Robert Tsao Hsing-Cheng – Chairman Emeritus, United Microelectronics Corporation • Prof Jitendra Singh – Dean & Shaw Foundation Chair, Nanyang Business School, Nanyang Technological University • Ms Janet Young – Managing Director and Regional Head MNC (Commercial Corporates) , Bank of America • Mr Ko Kheng Hwa – Managing Director, Economic Development Board • Mr Thomas Chua Kee Seng – Chairman and Managing Director, Teckwah Industrial Corporation Ltd 100 High Street, #09-01, The Treasury, Singapore 179434 T (65) 6225 9911 F (65) 6332 7260 www.mti.gov.sg PRESS RELEASE • COL Ng Chee Meng – Director, Joint Operations Department, Ministry of Defence In addition, one member of SPRING Singapore Board, Mr Lim Boon Wee, Deputy Secretary, Ministry of Transport, is re-appointed for a two- year term. -

Factsheet on CORENET

Factsheet on CORENET Project Details 1. Name of agency : Building and Construction Authority (BCA) 2. Project name : One-stop CORENET System 3. Project URL : http://www.corenet.gov.sg/ 4. Award category won : Shared Systems & Services What is CORENET? CORENET (Construction & Real Estate Network) is a one-stop shop for building professionals to make electronic submissions to BCA or any of the other 15 government regulatory authorities from anywhere at any time (24/7), including: Agri-Food & Veterinary Authority (AVA) Building and Construction Authority (BCA) Housing & Development Board (HDB) National Parks Board (NParks) Urban Redevelopment Authority (URA) National Environment Agency (NEA) - Central Building Plan and Pollution Control Public Utilities Board (PUB) - Drainage, Sewerage and Water Fire Safety and Shelter Department (FSSD) Infocomm Development Authrority (iDA) Land Transport Authority (LTA) Maritime and Port Authority of Singapore (MPA) Defence Science & Technology Agency (DSTA) Singapore Land Authority (SLA) Energy Market Authority (EMA) JTC Corporation (JTC) City Gas Pte Ltd (as Trustee) CORENET also provides one-stop electronic information (including codes & regulations, as well as events) relating to building and construction. Latest initiative: 3-Dimensional Building Information Model (BIM) e-submission can be done via CORENET. Benefits of using CORENET The pro-business initiative has transformed a time-consuming and complex building plan and construction permit submission process into one which is highly efficient. Since the launch of the system in 2001, the building industry has made over 3.54 million online submissions, with an average of more than 500,000 submissions made annually for the last three years. There are 13,138 registered users to date. -

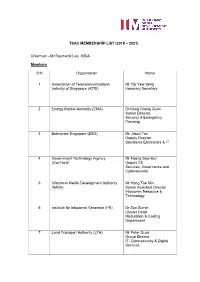

Tsac Membership List (2018 – 2021)

TSAC MEMBERSHIP LIST (2018 – 2021) Chairman - Mr Raymond Lee, IMDA Members S/N Organisation Name 1 Association of Telecommunications Mr Yip Yew Seng Industry of Singapore (ATIS) Honorary Secretary 2 Energy Market Authority (EMA) Dr Kang Cheng Guan Senior Director Security & Emergency Planning 3 Enterprise Singapore (ESG) Mr Jason Tan Deputy Director Standards Electronics & IT 4 Government Technology Agency Mr Foong Sew Bun (GovTech) Deputy CE Services, Governance and Cybersecurity 5 Infocomm Media Development Authority Mr Hong Tse Min (IMDA) Senior Assistant Director Infocomm Resource & Technology 6 Institute for Infocomm Research (I2R) Dr Sun Sumei Cluster Head Modulation & Coding Department 7 Land Transport Authority (LTA) Mr Peter Quek Group Director IT, Cybersecurity & Digital Services 8 M1 Limited Mr Denis Seek CTO 9 Mediacorp Pte Ltd Mr Anil Nihalani Head Digital Products & Technology 10 Nanyang Technological University (NTU) Dr Teh Kah Chan Associate Professor School of EEE 11 National University of Singapore (NUS) Dr Biplab Sikdar Associate Professor Department of ECE 12 Singapore Telecommunications Ltd Mr Edmund Quek Han Yeow (Singtel) Director Radio Network Quality 13 Singapore Institute of Technology (SIT) Dr Peter Loh Kok Keong Associate Professor and Deputy Programme Director Infocomm Technology Cluster 14 StarHub Ltd Ms Sarah Tay AVP Mobile 15 TPG Telecom Pte Ltd Mr Kian Kwan Chang Core Director Associate Members S/N Organisation Name 1 Ericsson Telecommunications Pte Ltd Mr Samid Tennakoon Chief Technology Officer 2 Huawei -

Clean Energy Industry in Singapore

CLEAN ENERGY INDUSTRY IN SINGAPORE CLEAN ENERGY INDUSTRY IN SINGAPORE 1 CLEAN ENERGY INDUSTRY OVERVIEW The Cleantech Industry is a strategic economic growth area of Singapore. In 2007, SGD350 million was committed by the Singapore government to the clean energy industry for the purpose of advancing research & development, and for capability development. Singapore’s Cleantech industry can be broken into two key sub-sectors – Clean Energy and Water Technologies. It is estimated that the clean energy industry itself would contribute around SGD1.7 billion to Singapore ‘s GDP by 2015 and create 7,000 jobs in the various areas of solar power, fuel cells, wind power, energy efficiency and carbon services. (The all- encompassing cleantech industry is predicted to contribute SGD3.4 billion to Singapore’s GDP and generate 18,000 new jobs by 2015.) Singapore’s natural geography precludes it from adopting many natural alternative energy solutions: Tidal, wave and ocean thermal power are not feasible as most of the sea space is dedicated to the shipping, logistics and other port purposes. Hydroelectric power relies on the gravitational force of falling or flowing water, but Singapore lacks a major river system for that to be harnessed. Wind energy is also still a flimsy option for Singapore as the country’s average wind speeds are too weak to justify the economic use of large wind turbines; furthermore, Singapore does not have sufficient land for commercial wind turbines. Geothermal energy is geographically impossible, as it is typically limited to the tectonic plate boundaries. Given Singapore’s limitations, solar photovoltaic (PV) and biofuels have been determined to be the most viable options for renewable energy. -

Singapore, Your Global Technology Partner

Singapore, Your Global Technology Partner Enterprise Singapore Singapore Economic Development Board 23 May 2019 Introduction AGENCIES UNDER MINISTRY OF TRADE AND INDUSTRY Minister for Trade and Industry Minister-in-charge of Trade Relations Mr. Chan Chun Seng Mr. S Iswaran Economic Enterprise Singapore Singapore Tourism Board Sentosa Development Development JTC Corporation Corporation Board Department of Statistics Agency for Science, Competition Commission Energy Market Authority Technology and of Singapore Research Manufacturing % that each industry to GDP contributes the industry each that % Business Services 2018 GDP: Financial & Insurance S$487.1 bn (~US$359.7 bn) Wholesale & Retail 2018 GDP Growth: 3.2% Transport & Communications Construction & Utilities 2019 GDP Others growth forecast: 1.5% - 3.5% Source: Economic Survey of Singapore 2018, MTI GLOBAL LEADERSHIP POSITIONS Singapore – A globally competitive manufacturing hub AEROSPACE LOGISTICS MARINE ENGINEERING Close to 25% of the Asia- World’s busiest transhipment 50% global market share for Pacific MRO (maintenance, hub. high specs jack-up rigs. repair and overhaul) market. BIOMEDICAL SCIENCES ENERGY & CHEMICALS ELECTRONICS Top 5 export oil trading and Refining hub globally, with 6 out of the top 10 drugs are 1.38 million barrels of 40% of global hard disk media manufactured in Singapore. refining capacity manufactured. (source: BP Statistical Review) HOME IN ASIA FOR GLOBAL BUSINESSES Singapore: Strategic geopolitical location at the crossroads of Asia 36,400 international companies -

Press R Elease

PRESS RELEASE BOARD CHANGES AT ENERGY MARKET AUTHORITY (EMA), ENTERPRISE SINGAPORE (ESG) AND JTC CORPORATION (JTC) 1. The Ministry of Trade and Industry (MTI) today announced board changes at the Energy Market Authority (EMA), Enterprise Singapore (ESG) and JTC Corporation (JTC). These changes will take effect on 1 April 2020. Energy Market Authority (EMA) 2. MTI has appointed a new Chairman and one new Member to the Board of EMA. They also re-appointed three Members to the Board of EMA: Appointment of Chairman • Mr Richard Lim Cherng Yih Chairman ST Logistics Appointment of New Board Member • Ms Paula Conboy Executive Consultant and Advisor Re-Appointment of Board Members • Mr Kon Yin Tong Managing Partner Foo Kon Tan LLP • Mr Zia Zaman Founder & Chief Executive Officer Lumen Lab Senior Vice President & Chief Innovation Officer MetLife Innovation Centre Pte Ltd • Ms Quah Ley Hoon Chief Executive Maritime and Port Authority of Singapore Enterprise Singapore (ESG) 3. MTI has appointed five new Members, and re-appointed the Chairman and ten Members to the Board of ESG: 100 High Street, #09-01, The Treasury, Singapore 179434 T (65) 6225 9911 F (65) 6332 7260 www.mti.gov.sg PRESS RELEASE Appointment of New Board Members • Ms Chin Wei Jia Chief Executive Officer HMI Group • Mr Luke Goh Deputy Secretary (Trade) Ministry of Trade and Industry • Mr Loke Wai San Executive Chairman and Director AEM • Mr Frank Phuan Chief Executive Officer & Executive Director Sunseap Group • Mr Daniel Wong Group General Manager Bee Cheng Hiang Hup Chong Foodstuff -

Energy Efficiency (EE) and Prioritising Energy Reduction Will Give Companies a 2

Responses to Feedback and Suggestions on Singapore’s Long-Term Low Emissions Development Strategy This Annex was prepared by the National Climate Change Secretariat (NCCS) together with the following agencies: the Ministry of Trade and Industry (MTI), the Economic Development Board (EDB), the Energy Market Authority (EMA), Enterprise Singapore (ESG), the Ministry of the Environment and Water Resources (MEWR), the National Environment Agency (NEA), PUB, Singapore’s National Water Agency (PUB), the Singapore Food Agency (SFA), the Ministry of National Development (MND), the Building and Construction Authority (BCA), the Housing and Development Board (HDB), the National Parks Board (NParks), the Urban Redevelopment Authority (URA), the Ministry of Finance (MOF), the Monetary Authority of Singapore (MAS), the Ministry of Transport (MOT), the Land Transport Authority (LTA), the Maritime and Port Authority of Singapore (MPA), the Civil Aviation Authority of Singapore (CAAS), the National Research Foundation (NRF), the National Population and Talent Division (NPTD), the Health Promotion Board (HPB) and the Ministry of Education (MOE). This document will be updated regularly as the Government continues to study the suggestions further and work with all stakeholders in developing implementation plans to realise Singapore’s LEDS. Contents A: Energy Use Reduction and Efficiency Improvements ....................................................................... 2 B: Decarbonising the Transport Sector ................................................................................................ -

The Development and Improvement of Instructions

ROOFTOP SOLAR POWER PRODUCTION POTENTIAL OF EXISTING PUBLIC HOUSING BUILDINGS IN SINGAPORE Dissertation in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of BACHELOR OF SCIENCE WITH A MAJOR IN SUSTAINABLE ENERGY TRANSITION Uppsala University Department of Earth Sciences, Campus Gotland Liew Chiat Chee Jamie 2021.06.25 ROOFTOP SOLAR POWER PRODUCTION POTENTIAL OF EXISTING PUBLIC HOUSING BUILDINGS IN SINGAPORE Dissertation in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of BACHELOR OF SCIENCE WITH A MAJOR IN SUSTAINABLE ENERGY TRANSITION Uppsala University Department of Earth Sciences, Campus Gotland Approved by: Supervisor, Christian Lewander Examiner, Simon Davidsson Kurland 2021.06.25 iii ABSTRACT The importance of increasing renewable energy production to facilitate a sustainable energy transition has been well-discussed and reinforced worldwide. In land- and resource-scarce and tropical Singapore, solar has been deemed the most feasible renewable energy technology for the country moving forward. Previous studies have focused on assessing the feasibility of various solar technologies. This paper instead analyses the rooftop solar power production potential of existing high-rise residential buildings in Singapore, and thus contributes to reaching the national solar goal using geographic information system geospatial imagery. For this study, the chosen focus area is the south of Jurong East in Singapore. Results show that solar deployment on all available public high-rise residential building rooftop areas in the focus area will be able to generate a total potential solar peak power and annual solar energy output of 2-megawatt peak and 2.8-gigawatt hour per year respectively. This equates to meeting the energy demand of 679 public residential apartments in the focus area and meeting 0.18% of the national solar goal of reaching 1.5- gigawatt peak by 2025. -

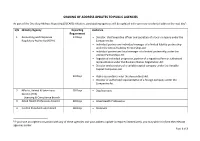

Sharing of Address Updates to Public Agencies

SHARING OF ADDRESS UPDATES TO PUBLIC AGENCIES As part of the One Stop Address Reporting (OSCARS) initiative, participating agencies will be updated with your new residential address the next day1: S/N Ministry/Agency Reporting Audience Requirement 1 Accounting and Corporate 14 Days Director, chief executive officer and secretary of a local company under the Regulatory Authority (ACRA) Companies Act Individual partner and individual manager of a limited liability partnership under the Limited Liability Partnerships Act Individual partner and local manager of a limited partnership under the Limited Partnerships Act Registered individual proprietor, partner of a registered firm or authorised representative under the Business Names Registration Act Director and secretary of a variable capital company under the Variable Capital Companies Act 30 Days Public accountant under the Accountants Act Director or authorised representative of a foreign company under the Companies Act 2 NParks, Animal & Veterinary 28 Days Dog licensees Service (AVS) – Licensing & Compliance branch 3 Allied Health Professions Council 28 Days Allied Health Professions 4 Central Provident Fund Board 28 Days Members 1If you have an urgent transaction with any of these agencies and your address update is required immediately, you may wish to inform the relevant agencies earlier. Page 1 of 3 5 Energy Market Authority 7 Days Licensed gas service workers 6 Housing and Development Board 28 Days Registrants for residential flats & tenants of non-residential premises -

Handbook for Solar Photovoltaic (PV) Systems

Handbook for Solar Photovoltaic (PV) Systems 1 Contents 1 Solar Photovoltaic (“PV”) Systems – An Overview 4 1.1 Introduction 4 1.2 Types of Solar PV System 5 1.3 Solar PV Technology 6 • Crystalline Silicon and Thin Film Technologies 8 • Conversion Efficiency 8 • Effects of Temperature 9 1.4 Technical Information 10 2 Solar PV Systems on a Building 12 2.1 Introduction 12 2.2 Installation Angle 12 2.3 Avoid Shading PV Modules 13 2.4 Aesthetic and Creative Approaches in Mounting PV Modules 14 2.5 Solar PV Output Profile 14 2.6 Solar PV Yield 15 2.7 Cost of a Solar PV System 15 3 Appointing a Solar PV System Contractor 16 3.1 Introduction 16 3.2 Getting Started 17 • Get an Experienced and Licensed Contractor 17 • Choosing Between Bids 17 • Solar PV System Warranty 17 • Regular Maintenance 19 • Other Relevant Matters 19 4 Solar PV System Installation Requirements 20 4.1 Electrical Installation Licence 20 4.2 Electrical Safety Standards and Requirements 20 4.3 Application of Electrical Installation Licence 21 4.4 Conservation and Development Control Requirements 21 4.5 Guidelines on Conservation and Development Control 21 4.6 Structural Safety and Lightning Protection 22 • Structural Safety 22 • Lightning Protection 22 4.7 Connection to the Power Grid 22 4.8 Get Connected to the Power Grid 23 4.9 Sale of Solar PV Electricity 23 4.10 Design and Installation Checklist 27 5 Operations and Maintenance 28 5.1 Operations of Solar PV Systems 28 5.2 Recommended Preventive Maintenance Works 29 Appendices APPENDIx A – EXAMPLES OF SOLAR PV SYSTEM ON BUILDINGS -

Energy Management and Economics

Energy Management and Economics Energy Management and Economics Tay Cher Seng April 2016 1 Energy Management and Economics © 2016 The Institution of Engineers, Singapore and National Environment Agency. All rights reserved. No part of this manual may be reproduced, distributed, transcribed, stored in a retrieval system, translated into any language or computer language or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior written permission of the copyright owner. The copyright owners give no warranties and make no representations about the contents of this manual and specifically disclaim any implied warranties or merchantability or fitness for any purpose. The copyright owners reserve the right to revise this manual and to make changes from time to time in its contents without notifying any person of such revisions or changes. 2 Energy Management and Economics Foreword Singapore has joined the world community in pledging at the UN climate change talks in Paris (the 21st Conference of the Parties, or COP 21) to reduce greenhouse gas emissions and limit global warming. In the December 2015 conference, Singapore has made a commitment to reduce our Emissions Intensity by 36% from 2005 levels by 2030, and stabilise our greenhouse gas emissions with the aim of peaking around 2030. Given Singapore’s limited access to renewable energy, this pledge is an ambitious one. It will require the concerted effort by all stakeholders, including the government, businesses, households and individuals to achieve this target. The Singapore Certified Energy Manager (SCEM) programme is targeted at engineers and managers who manage manufacturing facilities and buildings and provide energy services or engineering consulting services.