The Films of Tsai Ming-Liang

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

REBELS of the NEON GOD (QUING SHAO NIAN NE ZHA) Dir

bigworldpictures.org presents Booking contact: Jonathan Howell Big World Pictures [email protected] Tel: 917-400-1437 New York and Los Angeles Press Contact: Sasha Berman Shotwell Media Tel: 310-450-5571 [email protected] NY THEATRICAL RELEASE: APRIL 10TH LA THEATRICAL RELEASE: JUNE 12TH SYNOPSIS REBELS OF THE NEON GOD (QUING SHAO NIAN NE ZHA) Dir. Tsai Ming-liang Taiwan / 1992/2014 / 106 min / DCP! In Mandarin, with English subtitles Aspect ratio: 1.85:1 Sound: Dual Mono Best First Film – Nantes Three Continents Film Festival Best Film – International Feature Film Competition – Torino Intl. Festival of Young Cinema Best Original Score – Golden Horse Film Festival Tsai Ming-liang emerged on the world cinema scene in 1992 with his groundbreaking first feature, REBELS OF THE NEON GOD. His debut already includes a handful of elements familiar to fans of subsequent work: a deceptively spare style often branded “minimalist”; actor Lee Kang-sheng as the silent and sullen Hsiao-kang; copious amounts of water, whether pouring from the sky or bubbling up from a clogged drain; and enough urban anomie to ensure that even the subtle humor in evidence is tinged with pathos. The loosely structured plot involves Hsiao-kang, a despondent cram school student, who becomes obsessed with young petty thief Ah-tze, after Ah-tze smashes the rearview mirror of a taxi driven by Hsiao-kang’s father. Hsiao-kang stalks Ah-tze and his buddy Ah-ping as they hang out in the film’s iconic arcade (featuring a telling poster of James Dean on the wall) and other locales around Taipei, and ultimately takes his revenge. -

Friday, April 10 6:30 T1 Days. 2020. Taiwan. Directed by Tsai Ming

Tsai Ming-Liang: In Dialogue with Time, Memory, and Self April 10 - 26, 2020 The Roy and Niuta Titus Theaters Friday, April 10 6:30 T1 Days. 2020. Taiwan. Directed by Tsai Ming-Liang 127min. Saturday, April 11 2:00 T2 Goodbye, Dragon Inn. 2003. Taiwan. Directed by Tsai Ming-Liang. 82 min. 4:00 T1 (Lobby) Tsai Ming-Liang: Improvisations on the Memory of Cinema 6:30 T1 Vive L’Amour. 1994. Taiwan. Directed by Tsai Ming-Liang. 118 min. Sunday, April 12 2:30 T2 Face. 2009. Taiwan/France. Directed by Tsai Ming-Liang. 138 min. Monday, April 13 6:30 T1 No Form. 2012. Taiwan. Directed by Tsai Ming-Liang 20 min. Followed by: Journey to the West. 2014. Taiwan. Directed by Tsai Ming-Liang. 56 min. Tuesday, April 14 4:30 T1 Rebels of the Neon God. 1992. Taiwan. Directed by Tsai Ming-Liang. 106 min. Wednesday, April 15 4:00 T2 The River. 1997. Taiwan. Directed by Tsai Ming-Liang. 115 min. 6:30 T2 The Missing. 2003. Taiwan. Directed by Lee Kang-Sheng. 87 min. Preceded by: Single Belief. 2016. Taiwan. Directed by Lee Kang-Sheng. 15 min. Thursday, April 16 4:00 T2 I Don’t Want to Sleep Alone. 2006. Taiwan. Directed by Tsai Ming-Liang. 115 min. 7:00 T2 What Times Is It There? 2001. Taiwan. Directed by Tsai Ming-Liang. 116 min. Friday, April 17 4:00 T2 The Hole. 1998. Taiwan. Directed by Tsai Ming-Liang. 93 min. 7:00 T1 Stray Dogs. 2013. Taiwan. Directed by Tsai Ming-Liang. -

The Iafor Journal of Media, Communication & Film

the iafor journal of media, communication & film Volume 3 – Issue 1 – Spring 2016 Editor: James Rowlins ISSN: 2187-0667 The IAFOR Journal of Media, Communication & Film Volume 3 – Issue – I IAFOR Publications Executive Editor: Joseph Haldane The International Academic Forum IAFOR Journal of Media, Communication & Film Editor: James Rowlins, Singapore University of Technology and Design, Singapore Associate Editor: Celia Lam, University of Notre Dame Australia, Australia Assistant Editor: Anna Krivoruchko, Singapore University of Technology and Design, Singapore Advisory Editor: Jecheol Park, National University of Singapore, Singapore Published by The International Academic Forum (IAFOR), Japan Executive Editor: Joseph Haldane Editorial Assistance: Rachel Dyer IAFOR Publications. Sakae 1-16-26-201, Naka-ward, Aichi, Japan 460-0008 IAFOR Journal of Media, Communication & Film Volume 3 – Issue 1 – Spring 2016 IAFOR Publications © Copyright 2016 ISSN: 2187-0667 Online: JOMCF.iafor.org Cover photograph: Harajuku, James Rowlins IAFOR Journal of Media, Communication & Film Volume 3 – Issue 1 – Spring 2016 Edited by James Rowlins Table of Contents Notes on Contributors 1 Introduction 3 Editor, James Rowlins Interview with Martin Wood: A Filmmaker’s Journey into Research 5 Questions by James Rowlins Theorizing Subjectivity and Community Through Film 15 Jakub Morawski Sinophone Queerness and Female Auteurship in Zero Chou’s Drifting Flowers 22 Zoran Lee Pecic On Using Machinima as “Found” in Animation Production 36 Jifeng Huang A Story in the Making: Storytelling in the Digital Marketing of 53 Independent Films Nico Meissner Film Festivals and Cinematic Events Bridging the Gap between the Individual 63 and the Community: Cinema and Social Function in Conflict Resolution Elisa Costa Villaverde Semiotic Approach to Media Language 77 Michael Ejstrup and Bjarne le Fevre Jakobsen Revitalising Indigenous Resistance and Dissent through Online Media 90 Elizabeth Burrows IAFOR Journal of Media, Communicaion & Film Volume 3 – Issue 1 – Spring 2016 Notes on Contributors Dr. -

What Time Is It There?

What Time Is It There? 404110603 Charlie Lee 404110093 Daniel Hsu 404110586 Dean Lee 405110466 Leo Bao 404110615 Rex Huang 404110471 Tim Liu 4. Dean -- different aspects of time -- characters in different time zones kang -- *constrained in his inner self and his time --connects with Chyi and then to Paris Mother -- connects via her religious belief (talking to the fish, watering the plant) -- *confines herself in her own imaginary world. Chyi -- Kang's "way out." -- * wrist watch: two time zones -- three time zones -- in the theatre *Also the railroad scenes 3 sex scenes -- good quote from Ebert to explain them. Chyi -- "experiment with the other woman? Rex -- Time, Space and Human Flows; You also discuss the possibility of Chyi being Kang's fantasy Multiple Time --> Human flows -- 1) Chyi crossing national boundaries; 2) daily encounters --Can time be changed? * He changes it first at home and then different spaces of flows and thus connects with human flows. What does he long for? --> They want to break through their present constraints. time-space convergence -- at the railroad scene --> no friction? Is Chyi part of Kang's fantasy of Paris? Also the Father at the end? Leo-- Symbols -- the meanings you discuss are all possible in this "minimalist" film.--You are producing stories out of it. -- Circle, watch, clock -- to change the clock. a romantic act to be in the same time zone with Chyi -- This is a 2001 film, so maybe mobile phone is not that prevalent. -- water --also a means of connection, besides being a means of survival -- plant --the three family members are connected through the plant. -

Aspects of Chinese Cinema Today

Aspects of Chinese Cinema Today By Toh, Hai Leong Spring 1997 Issue of KINEMA 1. THE TAIWANESE ANTONIONI: TSAI MING-LIANG’S DISPLACEMENT OF LOVE IN AN URBAN ENVIRONMENT NO, Tsai Ming-liang is not in fact Taiwanese. The bespectacled 40-year-old bachelor was born in Kuching, Sarawak (East Malaysia) and only came to Taiwan for a college education. After graduating with a degree in drama and film in Taiwan’s University, he settled there and impressed critics with several experimental plays and television movies such as Give Me A Home (1988), The Happy Weaver(1989), My Name is Mary (1990), Ah Hsiung’s First Love(1990). He made a brilliant film debut in 1992 with Rebels Of The Neon God and his film Vive l’amour shared Venice’s Golden Lion for Best Film with Milcho Manchevski’s Before The Rain (1994). Rebels of the Neon God, a film about aimless and nihilistic Taipei youths, won numerous awards abroad: Among them, the Best Film award at the Festival International Cinema Giovani (1993), Best Film of New Director Award of Torino Film Festival (1993), the Best Music Award, Grand Prize and Best Director Awards of Taiwan Golden Horse Festival (1992), the Best Film of Chinese Film Festival (1992), a bronze award at the Tokyo International Film Festival in 1993 and the Best Director Award and Leading Actor Award at the Nantes Festival des Trois Continents in 1994.(1) For the sake of simplicity, he will be referred to as ”Taiwanese”, since he has made Taipei, (Taiwan) his home. In fact, he is considered to be among the second generation of New Wave filmmakers in Taiwan. -

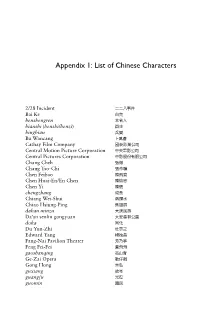

Appendix 1: List of Chinese Characters

Appendix 1: List of Chinese Characters 2/28 Incident 二二八事件 Bai Ke 白克 benshengren 本省人 bianshi (benshi/benzi) 辯士 bingbian 兵變 Bu Wancang 卜萬蒼 Cathay Film Company 國泰影業公司 Central Motion Picture Corporation 中央電影公司 Central Pictures Corporation 中影股份有限公司 Chang Cheh 張徹 Chang Tso-Chi 張作驥 Chen Feibao 陳飛寶 Chen Huai-En/En Chen 陳懷恩 Chen Yi 陳儀 chengzhang 成長 Chiang Wei- Shui 蔣謂水 Chiao Hsiung- Ping 焦雄屏 dahan minzu 大漢民族 Da’an senlin gongyuan 大安森林公園 doka 同化 Du Yun- Zhi 杜雲之 Edward Yang 楊德昌 Fang- Nai Pavilion Theater 芳乃亭 Feng Fei- Fei 鳳飛飛 gaoshanqing 高山青 Ge- Zai Opera 歌仔戲 Gong Hong 龔弘 guxiang 故鄉 guangfu 光復 guomin 國民 188 Appendix 1 guopian 國片 He Fei- Guang 何非光 Hou Hsiao- Hsien 侯孝賢 Hu Die 胡蝶 Huang Shi- De 黃時得 Ichikawa Sai 市川彩 jiankang xieshi zhuyi 健康寫實主義 Jinmen 金門 jinru shandi qingyong guoyu 進入山地請用國語 juancun 眷村 keban yingxiang 刻板印象 Kenny Bee 鍾鎮濤 Ke Yi-Zheng 柯一正 kominka 皇民化 Koxinga 國姓爺 Lee Chia 李嘉 Lee Daw- Ming 李道明 Lee Hsing 李行 Li You-Xin 李幼新 Li Xianlan 李香蘭 Liang Zhe- Fu 梁哲夫 Liao Huang 廖煌 Lin Hsien- Tang 林獻堂 Liu Ming- Chuan 劉銘傳 Liu Na’ou 劉吶鷗 Liu Sen- Yao 劉森堯 Liu Xi- Yang 劉喜陽 Lu Su- Shang 呂訴上 Ma- zu 馬祖 Mao Xin- Shao/Mao Wang- Ye 毛信孝/毛王爺 Matuura Shozo 松浦章三 Mei- Tai Troupe 美臺團 Misawa Mamie 三澤真美惠 Niu Chen- Ze 鈕承澤 nuhua 奴化 nuli 奴隸 Oshima Inoshi 大島豬市 piaoyou qunzu 漂游族群 Qiong Yao 瓊瑤 qiuzhi yu 求知慾 quanguo gejie 全國各界 Appendix 1 189 renmin jiyi 人民記憶 Ruan Lingyu 阮玲玉 sanhai 三害 shandi 山地 Shao 邵族 Shigehiko Hasumi 蓮實重彦 Shihmen Reservoir 石門水庫 shumin 庶民 Sino- Japanese Amity 日華親善 Society for Chinese Cinema Studies 中國電影史料研究會 Sun Moon Lake 日月潭 Taiwan Agricultural Education Studios -

The Many Faces of Tsai Ming-Liang: Cinephilia, the French Connection, and Cinema in the Gallery

IJAPS, Vol. 13, No. 2, 141–160, 2017 THE MANY FACES OF TSAI MING-LIANG: CINEPHILIA, THE FRENCH CONNECTION, AND CINEMA IN THE GALLERY Beth Tsai * Department of Cultural Studies and Comparative Literature, Stony Brook University, Stony Brook, United States email: [email protected] Published online: 15 July 2017 To cite this article: Tsai, B. 2017. The many faces of Tsai Ming-liang: Cinephilia, the French connection, and cinema in the gallery. International Journal of Asia Pacific Studies 13 (2): 141–160, https://doi.org/10.21315/ijaps2017.13.2.7 To link to this article: https://doi.org/10.21315/ijaps2017.13.2.7 ABSTRACT The Malaysia-born, Taiwan-based filmmaker Tsai Ming-liang's Visage (2009) is a film that was commissioned by the Louvre as part of its collection. His move to the museum space raises a number of questions: What are some of the implications of his shift in practice? What does it mean to have a film, situated in art galleries or museum space, invites us to think about the notion of cinema, spatial configuration, transnational co-production and consumption? To give these questions more specificity, this article willlook at the triangular relationship between the filmmaker's prior theatre experience, French cinephilia's influence, and cinema in the gallery, using It's a Dream (2007) and Visage as two case studies. I argue Tsai's film and video installation need to be situated in the intersection between the moving images and the alternative viewing experiences, and between the global and regional film cultures taking place at the theatre-within-a-gallery site. -

Four Asian Filmmakers Visualize the Transnational Imaginary Stephen Edward Spence University of New Mexico

University of New Mexico UNM Digital Repository American Studies ETDs Electronic Theses and Dissertations Spring 4-17-2017 "Revealing Reality": Four Asian Filmmakers Visualize the Transnational Imaginary Stephen Edward Spence University of New Mexico Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalrepository.unm.edu/amst_etds Part of the American Studies Commons, Film and Media Studies Commons, Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, and Transgender Studies Commons, and the Race, Ethnicity and Post-Colonial Studies Commons Recommended Citation Spence, Stephen Edward. ""Revealing Reality": Four Asian Filmmakers Visualize the Transnational Imaginary." (2017). https://digitalrepository.unm.edu/amst_etds/54 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Electronic Theses and Dissertations at UNM Digital Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in American Studies ETDs by an authorized administrator of UNM Digital Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. i Stephen Edward Spence Candidate American Studies Department This dissertation is approved, and it is acceptable in quality and form for publication: Approved by the Dissertation Committee: Rebecca Schreiber, Chairperson Alyosha Goldstein Susan Dever Luisela Alvaray ii "REVEALING REALITY": FOUR ASIAN FILMMAKERS VISUALIZE THE TRANSNATIONAL IMAGINARY by STEPHEN EDWARD SPENCE B.A., English, University of New Mexico, 1995 M.A., Comparative Literature & Cultural Studies, University of New Mexico, 2002 DISSERTATION Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy American Studies The University of New Mexico Albuquerque, New Mexico May, 2017 iii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS This project has been long in the making, and therefore requires substantial acknowledgments of gratitude and recognition. First, I would like to thank my fellow students in the American Studies Graduate cohort of 2003 (and several years following) who always offered support and friendship in the earliest years of this project. -

SOLO I GIOVANI HANNO DI QUESTI MOMENTI Racconti Di Cinema

SOLO I GIOVANI HANNO DI QUESTI MOMENTI Racconti di cinema A CURA DI FRANCESCA BISUTTI E FABRIZIO BORIN Solo i giovani hanno di questi momenti Racconti di cinema a cura di Francesca Bisutti e Fabrizio Borin © 2009 Libreria Editrice Cafoscarina ISBN 978-88-7543-224-9 Pubblicazione del Progetto “CAFOSCARICINEMA” realizzata con i contributi del Fondo di Ricerca di Ateneo dei curatori, Francesca Bisutti (Dipartimento di Americanistica, Iberistica e Slavistica) e Fabrizio Borin (Dipartimento di Storia delle Arti e Conservazione dei Beni Artistici “G. Mazzariol”) dell’Università Ca’ Foscari di Venezia In copertina: particolare di una foto di scena da Gioventù bruciata (Nicholas Ray, 1955) Libreria Editrice Cafoscarina Ca’ Foscari, Dorsoduro, 3259, 30123 Venezia www.cafoscarina.it Tutti i diritti riservati Solo i giovani hanno di questi momenti. Non intendo dire i giovanissimi. No. I giovanissimi, per essere esatti, non hanno momenti. È privilegio della prima gioventù vivere in anticipo sui propri giorni, nella bella continuità di speranze che non conosce pause né introspezione. Uno chiude dietro di sé il cancelletto della fanciullezza – ed entra in un giardino incantato. Là persino le ombre rilucono di promesse. […] Si procede riconoscendo i traguardi raggiunti dai nostri pre- decessori, eccitati e divertiti, accettando la buona e la cattiva fortuna insieme – le rose e le spine, come si dice – la vario- pinta sorte comune che tiene in serbo tante possibilità per chi le merita o, forse, per chi è fortunato. Sí. Si procede. E il tempo pure procede – finché si scorge di fronte a sé una linea d’ombra, che ci avverte che bisogna lasciare alle spalle anche la regione della prima gioventù. -

Download Original 631.47 KB

Franklin & Marshall College Rebels of the Neon God: An Inquiry on Time and Queerness Zixiang Lu FLM490 Independent Study Professor Sonia Misra April 05, 2021 Lu 2 Table of contents Introduction ………………………………………………………………………………… 03 A failure of retrieving control ………….…………………………………………………... 06 A Purer Structure of Time and Its Consequences…………………………...……………….21 Fabulation and Queer Temporality ……………………….…………………………………38 Conclusion…………………………………………………………………………………...50 Lu 3 Introduction A frequent participant in the world’s most prestigious film festivals, Tsai Ming-liang has always been a fascinating filmmaker to cinephiles. Malaysia-born and Taiwan-educated, Tsai has been producing feature films for nearly thirty years since the early 1990s. During these years, he has brought new inspirations to the Taiwanese New Cinema, marking himself as a unique and indispensable figure reflecting on the ideology of post-colonial urban Taiwan. What distinguishes him from other film directors of the same period, such as Edward Yang or Hou Hsiao-Hsien, is his unique filmmaking style that explores possibilities and thoughts. Since the start of his filmmaking career, he has been working on the front line of exploring the limits of narrative possibilities and political discourses. He has been experimenting on the de- dramatization of the narrative, the reduction of non-diegetic sounds and conversations, and the expression of queerness on screen. Through these experiments, his films have become a reserve full of enigmas that need to be vigorously decoded and explicated. To this end, this paper will focus on Tsai’s debut film, Rebels of the Neon God (1992), to articulate Tsai’s explorations within the film to further provide insights on his entire career. -

Tsai Ming-Liang, One of Contemporary Cinema's

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE TSAI MING-LIANG, ONE OF CONTEMPORARY CINEMA’S MOST CELEBRATED DIRECTORS, TO RECEIVE A MAJOR RETROSPECTIVE April 10–26, 2015 Astoria, New York, February 26, 2015—Tsai Ming-liang, the defining artist of Taiwan’s Second Wave of filmmakers, will be the subject of a major retrospective at Museum of the Moving Image, from April 10 through 26, 2015—the most comprehensive presentation of Tsai’s work ever presented in New York. Distinguished by a unique austerity of style and a minutely controlled mise-en-scene in which the smallest gestures give off enormous reverberations, Tsai’s films comprise one of the most monumental bodies of work of the past 25 years. And, with actor Lee Kang-sheng, who has appeared in every film, Tsai’s stories express an intimate acquaintance with despair and isolation, punctuated by deadpan humor. The Museum’s eighteen-film retrospective, Tsai Ming-liang, includes all of the director’s feature films as well as many rare shorts, an early television feature (Boys, 1991), and the revealing 2013 documentary Past Present, by Malaysian filmmaker Tiong Guan Saw. From Rebels of the Neon God (1992), which propelled Tsai into the international spotlight, and his 1990s powerhouse films Vive L’Amour (1994), The River (1997), and The Hole (1998); and films made in his native Malaysia, I Don’t Want to Sleep Alone (2006) and Sleeping on Dark Waters (2008); to his films made in France, What Time Is It There? (2001), Face (Visage) (2009), and Journey to the West (2014); the retrospective captures Tsai’s changing aesthetic: his gradual (but not continual) renouncement of classical cinematic techniques, an evolution that is also underscored by the shift from celluloid to digital. -

JBA Production, Homegreen Films and the Louvre Museum Present

JBA Production, Homegreen Films and the Louvre museum present FACE a Tsai Ming-Liang film Taiwan / France / Belgium / Netherlands 2009 / 2h21 / original version in French and Chinese / 35mm color 1,85 Dolby SRD / visa 119458 With Fanny Ardant, Laetitia Casta, Jean-Pierre Léaud, Lee Kang-Sheng, Lu Yi Ching, Norman Atun • And the exceptional appearances of Jeanne Moreau, Nathalie Baye, Mathieu Amalric, Yang Kuei Mei, Chen Chao Rong • Cinematography Liao Pen Jung • Sound Roberto Van Eijden, Jean Mallet, Philippe Baudhuin • Art direction Patrick Dechesne, Alain-Pascal Housiaux, Lee Tian Jue • Choreography Philippe Decouflé • Costumes Anne Dunsford, Wang Chia Hui with the participation of Christian Lacroix and the Comédie Française • Editing Jacques Comets • Coproducers Vincent Wang, Henri Loyrette, Joseph Rouschop, Stienette Bosklopper • A coproduction JBA Production (France), Homegreen Films (Taiwan), The Louvre museum, Tarantula (Belgium), Circe Films (Netherlands) and ARTE France Cinéma • In association with Fortissimo Films • With the support of CNC (France), GIO (Taiwan), Nederlands Fonds voor de Film (Netherlands), Eurimages (Conseil de l’Europe), La Région Ile-de-France • With the participation of ARTE France, Cinécinéma, Tax Shelter ING Invest, Department of Cultural Affairs Taipei City Government • Script developed with the support of the programme MEDIA and the Atelier of the Cannes Film Festival. Produced by Jacques Bidou and Marianne Dumoulin • Directed by Tsai Ming-Liang International sales Fortissimo Films International Sales: