Automated Software Testing Automated Software Testing

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

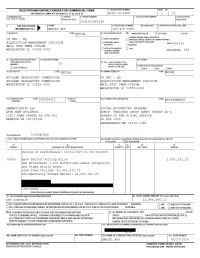

Order No. 31310019F0149 Under Contract No. GS35F192BA

2 of 27 19. 20. 21. 22. 23. 24. ITEM NO. SCHEDULE OF SUPPLIES/SERVICES QUANTITY UNIT UNIT PRICE AMOUNT Funded: $702,432.93 Accounting Info: Funded: $40,981.86 Accounting Info: Funded: $347,917.46 10001 Option Period 1 Ceiling Price 0.00 See Attachment 1 for Authorized Labor Categories and Fixed Hourly Rates Amount: $1,059,977.13(Option Line Item) Anticipated Exercise Date09/30/2020 Period of Performance: 10/01/2020 to 09/30/2021 20001 Option Period 2 Ceiling Price 0.00 See Attachment 1 for Authorized Labor Categories and Fixed Hourly Rates Amount: $847,176.84(Option Line Item) Anticipated Exercise Date09/30/2021 Period of Performance: 10/01/2021 to 09/30/2022 The obligated amount of award: $1,091,332.25. The total for this award is shown in box 26. 32a. QUANTITY IN COLUMN 21 HAS BEEN RECEIVED INSPECTED ACCEPTED, AND CONFORMS TO THE CONTRACT, EXCEPT AS NOTED: 32b. SIGNATURE OF AUTHORIZED GOVERNMENT REPRESENTATIVE 32c. DATE 32d. PRINTED NAME AND TITLE OF AUTHORIZED GOVERNMENT REPRESENTATIVE 32e. MA LING ADDRESS OF AUTHORIZED GOVERNMENT REPRESENTATIVE 32f. TELEPHONE NUMBER OF AUTHORIZED GOVERNMENT REPRESENTATIVE 32g. E-MA L OF AUTHORIZED GOVERNMENT REPRESENTATIVE 33. SHIP NUMBER 34. VOUCHER NUMBER 35. AMOUNT VERIFIED 36. PAYMENT 37. CHECK NUMBER CORRECT FOR COMPLETE PARTIAL FINAL PARTIAL FINAL 38. S/R ACCOUNT NUMBER 39. S/R VOUCHER NUMBER 40. PAID BY 41a. I CERTIFY THIS ACCOUNT IS CORRECT AND PROPER FOR PAYMENT 42a. RECEIVED BY (Print) 41b. SIGNATURE AND TITLE OF CERTIFY NG OFFICER 41c. DATE 42b. RECEIVED AT (Location) 42c. -

SOFTWARE DEVELOPMENT METHODOLOGIES Methodologies

SOFTWARE DEVELOPMENT METHODOLOGIES Methodologies • Waterfall • Prototype model • Incremental • Iterative • Spiral • RAD Waterfall • Sequential design process • Progress is seen as flowing steadily downwards (like a waterfall) through SDLC Prototyping • Creating prototypes of software applications i.e. incomplete versions of the software program being developed • A prototype typically simulates only a few aspects of, and may be completely different from, the final product. Incremental Build Model • The model is designed, implemented and tested incrementally (a little more is added each time ). • Finished when satisfies all the requirements. • Combines the elements of the waterfall model with the iterative philosophy of prototyping. Iterative and Incremental Development • Iterative and incremental development is any combination of both iterative design or iterative method and incremental build model for development. Incremental vs. Iterative A Bit Different Understanding Effort in Iterative Development Spiral Model • Combining elements of design and prototyping- in-stages • Combines the features of the prototyping and the waterfall model • The spiral model is intended for large, expensive and complicated projects • Advantages of top-down and bottom-up concepts RAD • Minimal planning and fast prototyping. • Developing instead of planning • The lack of pre- planning generally allows software to be written much faster, and makes it easier to change requirements. Agile • Group of software development methods • Based on iterative and incremental development • Most important phrases • self -organizing, cross - functional teams • adaptive planning, • evolutionary development and delivery, • a time-boxed iterative approach, • rapid and flexible response to change. • A conceptual framework • The Agile Manifesto in 2001.. -

Iterative Rework: the Good, the Bad, and the Ugly

COVER FEATURE Iterative Rework: The Good, the Bad, and the Ugly In software development, some rework is both inevitable and beneficial. But how much is too much and how little is too little? Understanding the nature of rework and why it occurs can help answer these questions. Richard E. ecause the creative processes in developing port the next version (bad that can turn ugly). Fairley and modifying software are subject to Understanding and correcting the root causes of Oregon Health and myriad external and changeable forces, it problems that result from too much or too little Science University is impossible to get all but the simplest rework can significantly increase productivity, B products right in one pass. Long experi- quality, developer morale, and customer satisfac- Mary Jane ence has shown the advantages of iterative devel- tion. Willshire opment, in which each iteration subsumes the pre- Colorado Technical vious iteration’s software and adds capabilities to ITERATIVE DEVELOPMENT MODELS University the evolving product to produce a next version. As All forms of iterative development provide a way developers build and validate the next version’s to capabilities, they rework the previous version to enhance its capabilities and fix defects discovered • continuously integrate and validate the evolving while integrating the new and old versions. product, Iterative development can take many forms, • frequently demonstrate progress, depending on the project’s goals: Iterative proto- • alert developers early on about problems, typing can help evolve a user interface. Agile devel- • deliver subset capabilities early on, and opment is a way to closely involve a prototypical • systematically incorporate the inevitable rework customer in a process that might repeat daily. -

Better Software Magazine

July/August 2014 www.TechWell.com USING PROCESS FRAMEWORKS Why fixed processes are not enough MOBILE APP DEVELOPMENT Build apps users will trust GROW YOUR SKILLS WITH TESTING TRAINING FROM SQE TRAINING M B I N O E C TRAINING WEEK The more training you take A N E D V the greater the savings! Green background Indicates S A TAMPA, FL TRAINING WEEK courses pre-approved for Project October 20–24, 2014 Management Institute PDUs. Maximize the impact of your training by combining courses in the same location. Combine a full week of training for the largest discount! MONDAY TUESDAY WEDNESDAY THURSDAY FRIDAY Software Tester Certification—Foundation Level Mastering Test Design Test Estimation and Testing Under Pressure Security Testing for Testing Professionals Exploring Usability Testing 2014 September 22–26, 2014 Measurement FALL SCHEDULE Washington, DC How to Break Software: Robustness Testing Unleashed Mobile Application Testing Nurture Grow October 20–24, 2014 Fundamentals of Agile Certification—ICAgile Agile Tester Certification—ICAgile Your Your TESTING Tampa, FL Risk-Driven Software Testing Testing with Use Cases Performance, Load, and Stress Testing Team Skills TRAINING November 3–7, 2014 Essential Test Management and Planning Leadership for Test Managers WEEKS San Francisco, CA SAN FRANCISCO, CA TRAINING WEEK Green background Indicates courses pre-approved for Project Green background Indicates November 3–7, 2014 Management Institute PDUs. WASHINGTON, DC TRAINING WEEK courses pre-approved for Project September 22–26, 2014 Management Institute -

System Development Life Cycle Methodology

2 System Development Life Cycle Methodology Learning Objectives : • To introduce the general concepts of various approaches of systems development, their framework, advantages and disadvantages; • To explain in detail the phases involved in Systems Development Life Cycle(SDLC); • To understand the key issues while acquiring or developing system for achieving goals set; • To discuss in detail various System Development Tools like – DFD, Decision Tree, Flowcharts etc.; and • To understand the auditors’ role in SDLC. 2.1 Introduction Information systems serve many different purposes, ranging from the processing of business transactions - to provide information needed to decide recurring issues, assisting senior officials with difficult strategy formulation, and linking office information and corporate data. But how do such complex information systems come into existence? Of course, through people. Technology has developed at a rapid pace but the most important aspect of any system is human know-how and the use of ideas to harness the computer so that it performs the required tasks. This process is essentially what system development is all about. To be of any use, a computer-based information system must function properly, be easy to use, and suit the organization for which it has been designed. If a system helps people to work more efficiently they will use it. If not, they will surely avoid it. 2.2 System Development Process In business, systems development refers to the process of examining a business situation with the intent of improving it through better procedures and methods. System development can generally be thought of as having two major components : System Analysis and System Design. -

Continuous Deployment of Pervasive Applications in Dynamic Environments Ozan Necati Günalp

Continuous deployment of pervasive applications in dynamic environments Ozan Necati Günalp To cite this version: Ozan Necati Günalp. Continuous deployment of pervasive applications in dynamic environments. Ubiquitous Computing. Université de Grenoble, 2014. English. NNT : 2014GRENM052. tel- 01215029 HAL Id: tel-01215029 https://tel.archives-ouvertes.fr/tel-01215029 Submitted on 13 Oct 2015 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. THÈSE Pour obtenir le grade de DOCTEUR DE L’UNIVERSITÉ DE GRENOBLE Spécialité : Informatique Arrêté ministériel : 7 août 2006 Présentée par Necati Ozan GÜNALP Thèse dirigée par Philippe LALANDA préparée au sein Laboratoire d’Informatique de Grenoble et de École Doctorale Mathématiques, Sciences et Technologies de l’Information, Informatique Déploiement continu des applications pervasives en milieux dynamiques Thèse soutenue publiquement le 13 Novembre 2014, devant le jury composé de : Mme Frédérique LAFOREST Professeur à Université de Saint Etienne, Présidente Mr Christian BECKER Professor at Universität Mannheim, -

Advanced Systems Analysis Semester One, 2011-2012 Answer ALL Questions in Section a and TWO Questions from Section B

CC3018NI – Advanced Systems Analysis Semester One, 2011-2012 Answer ALL questions in Section A AND TWO questions from Section B. Section A – includes Short Answer Questions 1-5 and Question 6 based on a Case Study. Answer all questions 1. Explain the following terms in relation to software development – giving two examples of each: a) problem domain b) model. (6 marks) Problem Domain: A problem domain is the area of expertise or application that needs to be examined to solve a problem. A problem domain is simply looking at only the topics of an individual's interest, and excluding everything else. Model: A model is an abstraction of some aspect of an existing or planned system. Mod- els are created to serve particular purposes, for example, to present a human-understandable description of some aspect of a system or to present information in a form that can be mechanically analyzed. 2. Summaries the general areas of guidance which might be given by a Software Development Method. (6 marks) 1) Identification of required software 2) Analysis of the software requirements 3) Detailed specification of the software requirements 4) Software design 5) Programming 6) Testing 7) Maintenance 3. Write brief notes on each of the following pairs of terms: a) i) Structured ii) Object-Oriented b) i) Waterfall ii) Incremental/Iterative c) i) Heavyweight ii) Lightweight (6 marks Structured Programming: (sometimes known as modular programming) is a subset of procedural programming that enforces a logical structure on the program being written to make it more efficient and easier to understand and modify. -

How Should We Estimate Agile Software Development Projects and What Data Do We Need?

Presented at the 2017 ICEAA Professional Development & Training Workshop www.iceaaonline.com/portland2017 How Should We Estimate Agile Software Development Projects And What Data Do We Need? Glen B. Alleman, Prime PM Thomas J. Coonce, Institute for Defense Analyses Presented at the 2017 ICEAA Professional Development & Training Workshop www.iceaaonline.com/portland2017 Agenda Overview of Software Development Life Cycle Models Why traditional parametric estimating tools do not help estimate a software project developed using the Agile model Explain and demonstrate the “nearest neighbor” analogy technique to estimate Agile software projects Data and actions needed to implement the nearest neighbor technique 2 Presented at the 2017 ICEAA Professional Development & Training Workshop www.iceaaonline.com/portland2017 Learning Objectives Understand different Software Life Cycle Development Models Understand how traditional parametric tools are not appropriate for agile-developed software Understand the cost and schedule drivers of an Agile-developed SW project Understand a proposed “nearest neighbor” analogy method of estimating Agile SW projects View minor revisions needed to DoD’s Software Resource Data Report (SRDR) to support this method 3 Presented at the 2017 ICEAA Professional Development & Training Workshop www.iceaaonline.com/portland2017 Software Development Life Cycle Models Waterfall Incremental development; Evolutionary development; Rapid application development (RAD); Spiral development; and Agile development 4 Presented -

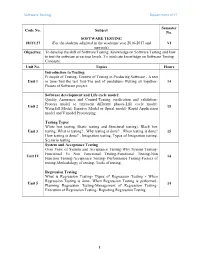

Software Testing Department of IT

Software Testing Department of IT Semester Code No. Subject No. SOFTWARE TESTING 18ITU27 (For the students admitted in the academic year 2016-2017 and VI onwards) Objective: To develop the skill of Software Testing. Knowledge on Software Testing and how to test the software at various levels. To inculcate knowledge on Software Testing Concepts. Unit No. Topics Hours Introduction to Testing: Principle of Testing- Context of Testing in Producing Software - A test Unit 1 in time-Test the test first-The end of pendulum- Putting all together- 14 Phases of Software project. Software development and Life cycle model: Quality Assurance and Control-Testing verification and validation- Process model to represent different phases-Life cycle model: Unit 2 15 Waterfall Model, Iterative Model or Spiral model- Rapid Application model and V model Prototyping . Testing Types White box testing (Static testing and Structural testing), Black box Unit 3 testing: What is testing? , Why testing is done? , When testing is done? 15 How testing is done? , Integration testing, Types of Integration testing, Scenario testing. System and Acceptance Testing Over View of System and Acceptance Testing-Why System Testing- Functional Vs Non Functional Testing-Functional Testing-Non Unit IV 14 Function Testing-Acceptance Testing- Performance Testing-Factors of testing-Methodology of testing- Tools of testing. Regression Testing What is Regression Testing- Types of Regression Testing - When Regression Testing is done- When Regression Testing is performed- Unit 5 14 Planning Regression Testing-Management of Regression Testing- Execution of Regression Testing- Reporting Regression Testing. 1 Software Testing Department of IT Text Books: 1. SrinivasanDesikan&Gopalswamy Ramesh, ―Software Testing Principles and Practices‖, Pearson Educatio,2006. -

Contract No. 31310020C0027

SOLICITATION/CONTRACT/ORDER FOR COMMERCIAL ITEMS 1. REQUISITION NUMBER PAGE OF OFFEROR TO COMPLETE BLOCKS 12, 17, 23, 24, & 30 OCIO-20-0240 1 86 2. CONTRACT NO. 3. AWARD/ 4. ORDER NUMBER 5. SOLICITATION NUMBER 6. SOLICITATION 31310020C0027 EFFECTIVE DATE ISSUE DATE 10/01/2020 7. FOR SOLICITATION a. NAME b. TELEPHONE NUMBER (No collect calls) 8. OFFER DUE DATE/LOCAL TIME INFORMATION CALL: BANU GOLDFEIZ 9. ISSUED BY CODE NRCHQ 10. THIS ACQUISITION IS UNRESTRICTED OR X SET ASIDE: 100.00 % FOR: WOMEN-OWNED SMALL BUSINESS SMALL BUSINESS US NRC - HQ (WOSB) ELIGIBLE UNDER THE WOMEN-OWNED X HUBZONE SMALL SMALL BUSINESS PROGRAM ACQUISITION MANAGEMENT DIVISION NAICS:518210 MAIL STOP TWFN-07B20M BUSINESS EDWOSB SERVICE-DISABLED 8(A) WASHINGTON DC 20555-0001 VETERAN-OWNED SIZE STANDARD: $35.00 SMALL BUSINESS 11. DELIVERY FOR FOB DESTINA- 12. DISCOUNT TERMS 13b. RATING TION UNLESS BLOCK IS 13a. THIS CONTRACT IS A MARKED 30 RATED ORDER UNDER 14. METHOD OF SOLICITATION SEE SCHEDULE DPAS (15 CFR 700) RFQ IFB RFP 15. DELIVER TO CODE NRCHQ 16. ADMINISTERED BY CODE NRCHQ NUCLEAR REGULATORY COMMISSION US NRC - HQ NUCLEAR REGULATORY COMMISSION ACQUISITION MANAGEMENT DIVISION WASHINGTON DC 20555-0001 MAIL STOP TWFN-07B20M WASHINGTON DC 20555-0001 17a. CONTRACTOR/ CODE 127407406 FACILITY 18a. PAYMENT WILL BE MADE BY CODE OFFEROR CODE NRC PAYMENTS 1 COMPETITIVE INNOVATIONS LLC NRC PAYMENTS ATTN MICHAEL KENNEDY NRCFISCALTREASURYGOV 200 N GLEBE RD STE 1025 ARLINGTON VA 222033759 TELEPHONE NO. 70369850002729 17b. CHECK IF REMITTANCE IS DIFFERENT AND PUT SUCH ADDRESS IN OFFER 18b. SUBMIT INVOICES TO ADDRESS SHOWN IN BLOCK 18a UNLESS BLOCK BELOW IS CHECKED SEE ADDENDUM 19. -

Software Development Life Cycle (SDLC)

Software Development Life Cycle (SDLC) SOFTWARE DEVELOPMENT LIFE CYCLE (SDLC) Simply Easy Learning by tutorialspoint.com tutorialspoint.com i ABOUT THE TUTORIAL SDLC Tutorial SDLC stands for Software Development Life Cycle. SDLC is the process consisting of a series of planned activities to develop or alter the software products. This tutorial will give you an overview of the SDLC basics, SDLC models available and their application in the industry. This tutorial also elaborates on the other related methodologies like Agile, RAD and Prototyping. Audience The SDLC tutorial is relevant to all software professionals contributing in any manner to the Software product development and its release. It is a handy reference for the quality stakeholders of a Software project and the program/project managers. By the end of this tutorial the readers will develop sound understanding of the SDLC and related concepts and will be in a position to select and follow the right model for a given Software project. Prerequisites There are no specific prerequisites for the SDLC tutorial and any software professional can go through this tutorial to get a bigger picture of how high quality software applications and products are designed. A good understanding of programming or testing or project management will give you an added advantage and help you gain maximum from this tutorial. Copyright & Disclaimer Notice All the content and graphics on this tutorial are the property of tutorialspoint.com. Any content from tutorialspoint.com or this tutorial may not be redistributed or reproduced in any way, shape, or form without the written permission of tutorialspoint.com. -

Software Development Methodology Revolution Based on Complexity Science - an Introduction to NSE Software Development Method

Software Development Methodology Revolution Based on Complexity Science - An Introduction to NSE Software Development Method Chi-Hung Kao1, Jay Xiong2 1The Jumpulse Center of Research and Incubation of Northwestern Polytechnic University 2 NSEsoftware., LLC., USA Abstract - This article introduces NSE (Nonlinear Software 2. Outline of the Revolutionary Solution Engineering) methodology based on complexity science. Offered by NSE Complying with the essential principles of complexity science, especially the Nonlinearity and the Generative Holism The revolutionary solution offered by NSE in software principles results that the whole of a complicated system may development methodology will be described in detail in this exist before building up its components. The characteristics article later. Here is the outline of the solution: and behaviors of the whole system emerge from the (1) It is based on complexity science by complying with the interactions of its components, so that NSE software essential principles of complexity science, particularly development methodology suggests almost all software the Nonlinearity principle and the Holism principle that development tasks and activities are performed holistically the whole of a complex system is greater than the sum of and globally Complying with W. Edwards Deming’s product its components – the characteristics and behaviors of the quality principle that “Cease dependence on inspection to whole emerge from the interaction of its components, so achieve quality. Eliminate the need for inspection on a mass that with NSE almost all tasks and activities in software basis by building quality into the product in the first place.”, development are performed holistically and globally. For NSE software development methodology is driven by defect instance, requirement changes are welcome to enhance prevention and traceability from the first to the final step in customers’ market competitional power, and order to ensure the quality of a software product.