Opening of Conference

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

HOUSE of ASSEMBLY Page 2215 HOUSE of ASSEMBLY Thursday 25 November 2010 the SPEAKER (Hon

Confidential and Subject to Revision Thursday 25 November 2010 HOUSE OF ASSEMBLY Page 2215 HOUSE OF ASSEMBLY Thursday 25 November 2010 The SPEAKER (Hon. L.R. Breuer) took the chair at 11:01 and read prayers. UNIVERSITY OF ADELAIDE (TRUST PROPERTY) AMENDMENT BILL Ms CHAPMAN (Bragg) (10:32): Obtained leave and introduced a bill for an act to amend the University of Adelaide Act 1971. Read a first time. Ms CHAPMAN (Bragg) (10:33): I move: That this bill be now read a second time. I move the University of Adelaide (Trust Property) Amendment Bill with a heavy heart. However, it is supported by the Liberal opposition and I am pleased to have its support. It is a bill to amend the University of Adelaide Act 1971. Members will be aware that the University of Adelaide was established by an act of this parliament, the first in South Australia and the third in Australia. It has a proud and respected history as an institution in this state. In 2003, the structure and independence of the governance of our universities was debated as a result of introduced bills for our three public universities in South Australia by then minister Lomax-Smith and supported by the opposition. An essential element of that bill was to provide greater autonomy in the handling of the university's own affairs, including its financial affairs and, in particular, the capacity to be able to buy, sell, lease, encumber or deal with its assets, and particularly real property. However, the reform retained in it an obligation to secure cabinet approval for very substantial property it owned, including the North Terrace precinct, Roseworthy and Waite campuses. -

Sixteen Years of Labor Government in South Australia, 2002-2018

AUSTRALASIAN PARLIAMENTARY REVIEW Parliament in the Periphery: Sixteen Years of Labor Government in South Australia, 2002-2018* Mark Dean Research Associate, Australian Industrial Transformation Institute, Flinders University of South Australia * Double-blind reviewed article. Abstract This article examines the sixteen years of Labor government in South Australia from 2002 to 2018. With reference to industry policy and strategy in the context of deindustrialisation, it analyses the impact and implications of policy choices made under Premiers Mike Rann and Jay Weatherill in attempts to progress South Australia beyond its growing status as a ‘rustbelt state’. Previous research has shown how, despite half of Labor’s term in office as a minority government and Rann’s apparent disregard for the Parliament, the executive’s ‘third way’ brand of policymaking was a powerful force in shaping the State’s development. This article approaches this contention from a new perspective to suggest that although this approach produced innovative policy outcomes, these were a vehicle for neo-liberal transformations to the State’s institutions. In strategically avoiding much legislative scrutiny, the Rann and Weatherill governments’ brand of policymaking was arguably unable to produce a coordinated response to South Australia’s deindustrialisation in a State historically shaped by more interventionist government and a clear role for the legislature. In undermining public services and hollowing out policy, the Rann and Wethearill governments reflected the path dependency of responses to earlier neo-liberal reforms, further entrenching neo-liberal responses to social and economic crisis and aiding a smooth transition to Liberal government in 2018. INTRODUCTION For sixteen years, from March 2002 to March 2018, South Australia was governed by the Labor Party. -

Government Gazette

No. 108 3 THE SOUTH AUSTRALIAN GOVERNMENT GAZETTE PUBLISHED BY AUTHORITY ALL PUBLIC ACTS appearing in this GAZETTE are to be considered official, and obeyed as such ADELAIDE, THURSDAY, 6 JULY 2000 CONTENTS Page Page Acts Assented To.........................................................................................................................4 (No. 160 of 2000)............................................................................................................27 Appointments Resignation, Etc...................................................................................................5 (No. 161 of 2000)............................................................................................................30 Corporations and District Councils—Notices...........................................................................62 (No. 162 of 2000)............................................................................................................33 Crown Lands Act 1929—Notice.................................................................................................6 (No. 174 of 2000)............................................................................................................60 Development Act 1993—Notices...............................................................................................6 Mental Health Act 1993 (No. 163 of 2000)........................................................................35 ExecSearch Consulting Services¾Notice..............................................................................69 -

Annual Report 1997-1998

OFFICE OF THE PUBLIC ADVOCATE ANNUAL REPORT 1997-98 30 September 1998 The Honourable Dean Brown MP Minister for Human Services PO Box 65 Rundle Mall ADELAIDE SA 5000 Dear Mr Brown I have much pleasure in forwarding to you the fourth Annual Report of the Public Advocate, as required under Section 24 of the Guardianship and Administration Act 1993. This report covers the period from 1 July 1997 until 30 June 1998. The fourth Annual Report summarises the work of the office during this period and reflects on some of the issues and trends that have been observed. As you will see, the office has been most productive during this period. Yours sincerely DR JOHN DAWES PUBLIC ADVOCATE 1 CONTENTS PUBLIC ADVOCATE’S REPORT . 3 OFFICE OF THE PUBLIC ADVOCATE Statement of purpose . 6 Accountability . 6 Legislative authority . 7 Legislative principles . 7 Philosophy . 7 Legislative functions . 8 Staffing . 9 Organisational structure . 12 Staffing issues . 12 GUARDIANSHIP Guardianship appointments for 1997-98 . 13 Issues arising out of guardianship . 15 Examples of guardianships - some case studies . 17 INVESTIGATION Investigations for 1997-98 . 20 Issues and advocacy arising out of investigation . 21 Examples of investigations - some case studies . 23 EDUCATION Provision of education sessions . 27 Education materials development . 29 OPA Web site . 30 List of pamphlets and resources . 31 External information requests, consultation and advocacy . 32 Future directions for the Education Unit . 33 ENQUIRIES Enquiries for 1997-98 . 35 ISSUES Work with other agencies . 38 The question of competence . 40 CORPORATE ISSUES Equal employment opportunity . 43 Occupational health and safety . 43 Freedom of information . -

Government Gazette

No. 7 183 EXTRAORDINARY GAZETTE THE SOUTH AUSTRALIAN GOVERNMENT GAZETTE PUBLISHED BY AUTHORITY ALL PUBLIC ACTS appearing in this GAZETTE are to be considered official, and obeyed as such ADELAIDE, TUESDAY, 15 JANUARY 2002 CONTENTS Page Appointments, Resignations, Etc............................................... 188 Fisheries Act 1982—Notices..................................................... 189 Proclamations............................................................................ 184 REGULATIONS Graffiti Control Act 2001 (No. 3 of 2002) ............................ 203 Summary Offences Act 1953 (No. 4 of 2002)....................... 204 Retail and Commercial Leases Act 1995 (No. 5 of 2002) ..... 205 South Australian Co-operative and Community Housing Act 1991 (No. 6 of 2002)................................................... 211 Retirement Villages Act 1987 (No. 7 of 2002)...................... 213 Gene Technology Act 2001 (No. 8 of 2002) ......................... 244 Chiropractors Act 1991 (No. 9 of 2002)................................ 297 Botanic Gardens and State Herbarium Act 1978— (No. 10 of 2002) ................................................................ 300 Housing and Urban Development (Administrative Arrangements) Act 1995 (No. 11 of 2002) ........................ 301 Warden’s Court—Rules ............................................................ 191 GOVERNMENT GAZETTE NOTICES ALL poundkeepers’ and private advertisements forwarded for publication in the South Australian Government Gazette must be PAID FOR PRIOR TO INSERTION; and all notices, from whatever source, should be legibly written on one side of the paper only and sent to Government Publishing SA so as to be received no later than 4 p.m. on the Tuesday preceding the day of publication. Phone 8207 1045 or Fax 8207 1040. E-mail: [email protected]. Send as attachments in Word format and please confirm your transmission with a faxed copy of your document, including the date the notice is to be published and to whom the notice will be charged. -

2020 Annual Review

Annual Review 2020 The Playford Memorial Trust supports high-achieving South Australian tertiary students studying in areas of strategic importance to the State playfordtrust.com.au The Playford Memorial Trust Inc. 02 From the Chair: 2019 in review • An exciting proposal to join the South I always enjoy receiving updates from our Australian Government in offering scholars, learning about the fascinating 40 new scholarships for Vocational work they are doing, and hearing about Education Training (VET) students in their commitment and contributions to our 2020 and 2021. This would broaden community, our nation and, in some cases, greatly the scope of the scholarships the world. Regrettably, we can’t publish offered in the VET sector and encourage every report submitted but each is an 2019 was a year of diversifying more students to take on vocational skills. important record of achievement. and expanding the scope of the Discussions are progressing well. The Trust’s ever-growing list of scholarships and awards offered • In partnership with the Leaders Institute achievements is in no small measure by the Playford Memorial Trust of South Australia, seven community due to the fine work of our support staff – leadership skills scholarships were and its partners. Vicki Evans, our Scholarship Executive; awarded in the Upper Spencer Gulf Mary Anne Fairbrother, who retired late region. In the coming year, we expect in 2019 after many years of service as our Our achievements included: to offer up to eight similar awards in Executive Officer, and Hayley Hasler, our • Providing financial support for 54 the northern suburbs of Adelaide. -

The Coorong Lower Lakes and Murray Mouth Directions for a Healthy Future

The Community Consultation Report: Murray Futures: Lower Lakes & Coorong Recovery Community Consultation Report The Coorong, Lower Lakes and Murray Mouth: Directions for a Healthy Future APPENDICES June 2009 Page 1 The Community Consultation Report: Murray Futures: Lower Lakes & Coorong Recovery Appendices Appendix 1 Promotion - Distribution Points 3 Appendix 2 Promotion - Media Coverage 6 Appendix 3 Promotion - Advertisements & Web Copy 7 Appendix 4 Community Information Sessions – Notes 22 Appendix 5 Community Information Sessions - PowerPoint Presentation 44 Appendix 6 Community Information Sessions - Feedback Survey 49 Appendix 7 Targeted Meetings - Notes 53 Appendix 8 Targeted Meetings - (Example) PowerPoint Presentation 64 Appendix 9 Written Submissions - List 67 Appendix 10 Written Submissions - Summaries 69 Appendix 11On-line Survey Report (from Ehrenberg-Bass) 107 Page 2 The Community Consultation Report: Murray Futures: Lower Lakes & Coorong Recovery Appendix 1 Promotion - Distribution Points Councils: Alexandrina Council Coorong District Council Strathalbyn Council Office Coorong District Council (Tailem Bend and Tintinara) Mt Barker District Council Rural City of Murray Bridge Libraries: Coomandook Community Library DEWHA Library Goolwa Public Library Meningie Community Library Mount Barker Community Library Mt Compass Library Murray Bridge Library National Library of Australia ACT Library Port Elliot Library SA Parliamentary Library State Library Adelaide Strathalbyn Community Library Tailem Bend Community Library Tintinara -

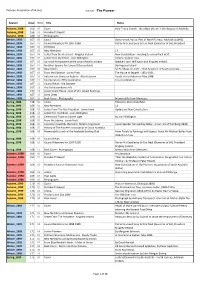

PASA Journals Index 2017 07 Brian.Xlsx

Pioneers Association of SA (Inc) Journal - "The Pioneer" Season Issue Item Title Notes Autumn_1998 166 00 Cover Holy Trinity Church - the oldest church in the diocese of Adelaide. Autumn_1998 166 01 President's Report Autumn_1998 166 02 Photographs Winter_1998 167 00 Cover Government House, Part of North Terrace, Adelaide (c1845). Winter_1998 167 01 Council Members for 1997-1998 Patron His Excellency Sir Eric Neal (Governor of SA), President Winter_1998 167 02 Portfolios Winter_1998 167 03 New Members 17 Winter_1998 167 04 Letter from the President - Kingsley Ireland New Constitution - meeting to review final draft. Winter_1998 167 05 Letter from the Editor - Joan Willington Communication lines. Winter_1998 167 06 Convivial Atmosphere at the Union Hotel Luncheon Speakers Joan Willington and Kingsley Ireland. Winter_1998 167 07 No Silver Spoons for Cavenett Descendants By Kingsley Ireland. Winter_1998 167 08 New Patron Sir Eric Neal, AC, CVO - 32nd Governor of South Australia. Winter_1998 167 09 From the Librarian - Lorna Pratt The House of Seppelt - 1851-1951. Winter_1998 167 10 Autumn sun shines on Auburn - Alan Paterson Coach trip to Auburn in May 1998. Winter_1998 167 11 Incorporation of The Association For consideration. Winter_1998 167 12 Council News - Dia Dowsett Winter_1998 167 13 The Correspondence File Winter_1998 167 14 Government House - One of SA's Oldest Buildings Winter_1998 167 15 Diary Dates Winter_1998 167 16 Back Cover - Photographs Memorabilia from Members. Spring_1998 168 00 Cover Edward Gibbon Wakefield. Spring_1998 168 01 New Members 14 Spring_1998 168 02 Letter From The Vice President - Jamie Irwin Update on New Constitution. Spring_1998 168 03 Letter fron the Editor - Joan Willington Spring_1998 168 04 Ceremonial Toast to Colonel Light By Joan Willington. -

Overview of Political Themes 2002 Final V1

Overview of Key Political and Policy Themes South Australia January to December 2002 Dr Haydon Manning, School of Social and Policy Studies, Flinders University Election 2002 During the decade and a half preceding 2002, South Australians experienced only four years of government by a party able to command a clear majority on the floor of the House of Assembly. The outcome of the 9 February 2002 State election altered nothing in this regard. The 2002 election result is summarised below for both houses – note, neither major party gained a majority of seats in the House of Assembly or sufficient seats to control the Legislative Council. Notably, the Liberal Party once again failed to form government after winning the majority of the two party preferred and first preference votes. House of Assembly: Election Outcome in Votes and Seats % Votes Change 1997- 2 Party Change Seats Seats (Primary) 2002 Preferred 2PP Won Change Liberal Party 40.0 -0.4 50.9 -0.6 20 -3* Labor Party 36.3 +1.1 49.1 +0.6 23 +2 Democrats 7.5 -8.9 National Party 1.5 -0.2 1 Indep/Others# 14.8 +8.6 3 +1 100 47 * Two Liberal seats won in 1997 changed prior to 2002 when sitting Liberals became independents and one independent joined the Liberal Party. # Includes Peter Lewis’ Community Leadership Independence Coalition Party (CLIC) Legislative Council: Election Outcome in Votes and Seats % Votes Change 1997- Initial Seats Seats in (Primary) 2002 Quota Won Chamber Liberal Party 40.1 +2.3 4.83 5 9 Labor Party 32.9 +2.3 3.96 4 7 Democrats 7.3 -9.4 0.88 1 3 National Party 0.5 -0.5 0.47 - Family First 4.0 +4.0 0.48 1 1 One Nation 1.8 +1.8 0.21 - Greens 2.8 +1.1 0.33 - S.A First 1.0 +1.0 0.12 - 1 * Others (18 groupings) 9.5 +5.7 na - 1 100 11 22 * Nicholas Xenophon, Independent No Pokies Campaign 1 Incumbent Premier, Rob Kerin, who had taken over from Premier John Olsen in October 2001 after Olsen was forced to resign for misleading the Parliament, failed to convince voters. -

Oh 955 Nick Minchin

STATE LIBRARY OF SOUTH AUSTRALIA J. D. SOMERVILLE ORAL HISTORY COLLECTION OH 955 Full transcript of an interview with Nick Minchin on 19 October 2010 By Susan Marsden for the EMINENT AUSTRALIANS ORAL HISTORY PROJECT Recording available on CD Access for research: Unrestricted Right to photocopy: Copies may be made for research and study Right to quote or publish: Publication only with written permission from the State Library OH 955 NICK MINCHIN NOTES TO THE TRANSCRIPT This transcript was created by the J. D. Somerville Oral History Collection of the State Library. It conforms to the Somerville Collection's policies for transcription which are explained below. Readers of this oral history transcript should bear in mind that it is a record of the spoken word and reflects the informal, conversational style that is inherent in such historical sources. The State Library is not responsible for the factual accuracy of the interview, nor for the views expressed therein. As with any historical source, these are for the reader to judge. It is the Somerville Collection's policy to produce a transcript that is, so far as possible, a verbatim transcript that preserves the interviewee's manner of speaking and the conversational style of the interview. Certain conventions of transcription have been applied (ie. the omission of meaningless noises, false starts and a percentage of the interviewee's crutch words). Where the interviewee has had the opportunity to read the transcript, their suggested alterations have been incorporated in the text (see below). On the whole, the document can be regarded as a raw transcript. -

Upholding the Australian Constitution, Volume 15

Upholding the Australian Constitution Volume Fifteen Proceedings of the Fifteenth Conference of The Samuel Griffith Society Stamford Plaza Adelaide Hotel, North Terrace, Adelaide, 23–25 May, 2003 © Copyright 2003 by The Samuel Griffith Society. All rights reserved. Table of Contents Foreword John Stone Dinner Address Hon Justice Ian Callinan, AC The Law: Past and Present Tense Introductory Remarks John Stone Chapter One Hon Len King, AC, QC An Experiment in Constitutional Reform – South Australia’s Constitutional Convention 2003 Chapter Two Hon Trevor Griffin The South Australian Constitutional Framework – Good, Bad or What? Chapter Three Professor Geoffrey de Q Walker The Advance of Direct Democracy Chapter Four Hon Peter Reith Let’s Give Democracy a Chance: Some Suggestions Chapter Five Professor Peter Howell South Australia and Federation Chapter Six Professor Philip Ayres John Latham in Owen Dixon’s Eyes i Chapter Seven Rt Hon Sir Harry Gibbs, GCMG, AC, KBE Teoh : Some Reflections Chapter Eight Hon Senator Nick Minchin Voluntary Voting Chapter Nine Julian Leeser Don’t! You’ll Just Encourage Them Chapter Ten Dr Geoffrey Partington Hindmarsh Island and the Fabrication of Aboriginal Mythology Chapter Eleven Keith Windschuttle Mabo and the Fabrication of Aboriginal History Concluding Remarks Rt Hon Sir Harry Gibbs, GCMG, AC, KBE Appendix I Professor David Flint, AM Presentation to Sir Harry Gibbs Appendix II Contributors ii Foreword John Stone The fifteenth Conference of The Samuel Griffith Society, which was held in Adelaide in May, 2003 coincided, as it happened, with the lead-up to the South Australian Constitutional Convention, and it was appropriate, therefore, that the program should mark that fact by the inclusion of four papers having to do with that (at the time of writing, still impending) event. -

Ministers Responsible for Agriculture Since Parliamentary Government Commenced in October 1856 and Heads of the Department of Agriculture/PISA/PIRSA

Ministers responsible for Agriculture since Parliamentary government commenced in October 1856 and Heads of the Department of Agriculture/PISA/PIRSA Dates Government Dates of Minister Ministerial title Name of Head of Date range portfolio Department Department of Head 1856– Boyle Travers 24.10.1856– Charles Bonney Commissioner of Crown 1857 Finniss 21.8.1857 Lands and Immigration 1857 John Baker 21.8.1857– William Milne Commissioner of Crown 1.9.1857 Lands and Immigration 1857 Robert Torrens 1.9.1857– Marshall McDermott Commissioner of Crown 30.10.1857 Lands and Immigration 1857– Richard Hanson 30.9.1857– Francis Stacker Dutton Commissioner of Crown 1860 2.6.1859 Lands and Immigration 2.6.1859– John Bentham Neales Commissioner of Crown 5.7.1859 Lands and Immigration 5.7.1859– William Milne Commissioner of Crown 9.5.1860 Lands and Immigration 1860– Thomas 9.5.1860– John Tuthill Bagot Commissioner of Crown 1861 Reynolds 20.5.1861 Lands and Immigration 1861 Thomas 20.5.1861– Henry Bull Templar Commissioner of Crown Reynolds 8.10.1861 Strangways Lands and Immigration 1861 George 8.10.1861– Matthew Moorhouse Commissioner of Crown Waterhouse 17.10.1861 Lands and Immigration 1861– George 17.10.1861– Henry Bull Templar Commissioner of Crown 1863 Waterhouse 4.7.1863 Strangways Lands and Immigration 1863 Francis Dutton 4.7.1863– Francis Stacker Dutton Commissioner of Crown 15.7.1863 Lands and Immigration 1863– Henry Ayers 15.7.1863– Lavington Glyde Commissioner of Crown 1864 22.7.1864 Lands and Immigration 1864 Henry Ayers 22.7.1864– William Milne