Routes and Roots FINAL TEXT.Indb

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

View Or Download Full Colour Catalogue May 2021

VIEW OR DOWNLOAD FULL COLOUR CATALOGUE 1986 — 2021 CELEBRATING 35 YEARS Ian Green - Elaine Sunter Managing Director Accounts, Royalties & Promotion & Promotion. ([email protected]) ([email protected]) Orders & General Enquiries To:- Tel (0)1875 814155 email - [email protected] • Website – www.greentrax.com GREENTRAX RECORDINGS LIMITED Cockenzie Business Centre Edinburgh Road, Cockenzie, East Lothian Scotland EH32 0XL tel : 01875 814155 / fax : 01875 813545 THIS IS OUR DOWNLOAD AND VIEW FULL COLOUR CATALOGUE FOR DETAILS OF AVAILABILITY AND ON WHICH FORMATS (CD AND OR DOWNLOAD/STREAMING) SEE OUR DOWNLOAD TEXT (NUMERICAL LIST) CATALOGUE (BELOW). AWARDS AND HONOURS BESTOWED ON GREENTRAX RECORDINGS AND Dr IAN GREEN Honorary Degree of Doctorate of Music from the Royal Conservatoire, Glasgow (Ian Green) Scots Trad Awards – The Hamish Henderson Award for Services to Traditional Music (Ian Green) Scots Trad Awards – Hall of Fame (Ian Green) East Lothian Business Annual Achievement Award For Good Business Practises (Greentrax Recordings) Midlothian and East Lothian Chamber of Commerce – Local Business Hero Award (Ian Green and Greentrax Recordings) Hands Up For Trad – Landmark Award (Greentrax Recordings) Featured on Scottish Television’s ‘Artery’ Series (Ian Green and Greentrax Recordings) Honorary Member of The Traditional Music and Song Association of Scotland and Haddington Pipe Band (Ian Green) ‘Fuzz to Folk – Trax of My Life’ – Biography of Ian Green Published by Luath Press. Music Type Groups : Traditional & Contemporary, Instrumental -

Savannah Scottish Games & Highland Gathering

47th ANNUAL CHARLESTON SCOTTISH GAMES-USSE-0424 November 2, 2019 Boone Hall Plantation, Mount Pleasant, SC Judge: Fiona Connell Piper: Josh Adams 1. Highland Dance Competition will conform to SOBHD standards. The adjudicator’s decision is final. 2. Pre-Premier will be divided according to entries received. Medals and trophies will be awarded. Medals only in Primary. 3. Premier age groups will be divided according to entries received. Cash prizes will be awarded as follows: Group 1 Awards 1st $25.00, 2nd $15.00, 3rd $10.00, 4th $5.00 Group 2 Awards 1st $30.00, 2nd $20.00, 3rd $15.00, 4th $8.00 Group 3 Awards 1st $50.00, 2nd $40.00, 3rd $30.00, 4th $15.00 4. Trophies will be awarded in each group. Most Promising Beginner and Most Promising Novice 5. Dancer of the Day: 4 step Fling will be danced by Premier dancer who placed 1st in any dance. Primary, Beginner and Novice Registration: Saturday, November 2, 2019, 9:00 AM- Competition to begin at 9:30 AM Beginner Steps Novice Steps Primary Steps 1. Highland Fling 4 5. Highland Fling 4 9. 16 Pas de Basque 2. Sword Dance 2&1 6. Sword Dance 2&1 10. 6 Pas de Basque & 4 High Cuts 3. Seann Triubhas 3&1 7. Seann Triubhas 3&1 11. Highland Fling 4 4. 1/2 Tulloch 8. 1/2 Tulloch 12. Sword Dance 2&1 Intermediate and Premier Registration: Saturday, November 2, 2019, 12:30 PM- Competition to begin at 1:00 PM Intermediate Premier 15 Jig 3&1 20 Hornpipe 4 16 Hornpipe 4 21 Jig 3&1 17 Highland Fling 4 22. -

Bowing Styles in Irish Fiddle Playing Vol 3

Bowing Styles in Irish Fiddle Playing Vol 3 David H. Lyth July 2016 2 This is the third volume of a series of transcriptions of Irish traditional fiddle playing. The others are `Bowing Styles in Irish Fiddle Playing Vol I' and `Bowing Styles in Irish Fiddle Playing Vol 2'. Volume 1 contains reels and hornpipes recorded by Michael Coleman, James Morrison and Paddy Killoran in the 1920's and 30's. Volume 2 contains several types of tune, recorded by players from Clare, Limerick and Kerry in the 1950's and 60's. Volumes I and II were both published by Comhaltas Ceoltoiri Eirann. This third volume returns to the players in Volume 1, with more tune types. In all three volumes, the transcriptions give the bowing used by the per- former. I have determined the bowing by slowing down the recording to the point where the gaps caused by the changes in bow direction can be clearly heard. On the few occasions when a gap separates two passages with the bow in the same direction, I have usually been able to find that out by demanding consistency; if a passage is repeated with the same gaps between notes, I assume that the directions of the bow are also repeated. That approach gives a reliable result for the tunes in these volumes. (For some other tunes it doesn't, and I have not included them.) The ornaments are also given, using the standard notation which is explained in Volumes 1 and 2. The tunes come with metronome settings, corresponding to the speed of the performance that I have. -

Civil Registrations of Deaths in Ireland, 1864Ff — Elderly Rose

Civil Registrations of Deaths in Ireland, 1864ff — Elderly Rose individuals in County Donegal, listed in birth order; Compared to Entries in Griffith's Valuation for the civil parish of Inver, county Donegal, 1857. By Alison Kilpatrick (Ontario, Canada) ©2020. Objective: To scan the Irish civil records for deaths of individuals, surname: Rose, whose names appear to have been recorded in Griffith's Valuation of the parish of Inver, county Donegal; and to consult other records in order to attempt reconstruction of marital and filial relationships on the off chance that descendants can make reliable connections to an individual named in Griffith's Valuation. These other records include the civil registrations of births and marriages, the Irish census records, historical Irish newspapers, and finding aids provided by genealogical data firms. Scope: (1) Griffith's Valuation for the parish of Inver, county Donegal, 1857. (2) The civil records of death from 1864 forward for the Supervisor's Registration District (SRD) of Donegal were the primary focus. Other SRDs within and adjacent to the county were also searched, i.e., Ballyshannon, Donegal, Dunfanaghy, Glenties, Inishowen, Letterkenny, Londonderry, Millford, Strabane, and Stranorlar. Limitations of this survey: (i) First and foremost, this survey is not a comprehensive one-name study of the Rose families of county Donegal. The purpose of this survey was to attempt to answer one specific question, for which:—see "Objective" above. (ii) The primary constraints on interpreting results of this survey are the absence of church and civil records until the 1860s, and the lack of continuity between the existing records. -

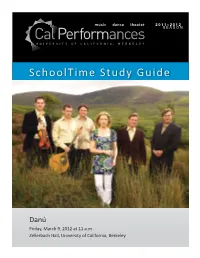

Danu Study Guide 11.12.Indd

SchoolTime Study Guide Danú Friday, March 9, 2012 at 11 a.m. Zellerbach Hall, University of California, Berkeley Welcome to SchoolTime! On Friday, March 9, 2012 at 11 am, your class will a end a performance by Danú the award- winning Irish band. Hailing from historic County Waterford, Danú celebrates Irish music at its fi nest. The group’s energe c concerts feature a lively mix of both ancient music and original repertoire. For over a decade, these virtuosos on fl ute, n whistle, fi ddle, bu on accordion, bouzouki, and vocals have thrilled audiences, winning numerous interna onal awards and recording seven acclaimed albums. Using This Study Guide You can prepare your students for their Cal Performances fi eld trip with the materials in this study guide. Prior to the performance, we encourage you to: • Copy the student resource sheet on pages 2 & 3 and hand it out to your students several days before the performance. • Discuss the informa on About the Performance & Ar sts and Danú’s Instruments on pages 4-5 with your students. • Read to your students from About the Art Form on page 6-8 and About Ireland on pages 9-11. • Engage your students in two or more of the ac vi es on pages 13-14. • Refl ect with your students by asking them guiding ques ons, found on pages 2,4,6 & 9. • Immerse students further into the art form by using the glossary and resource sec ons on pages 12 &15. At the performance: Students can ac vely par cipate during the performance by: • LISTENING CAREFULLY to the melodies, harmonies and rhythms • OBSERVING how the musicians and singers work together, some mes playing in solos, duets, trios and as an ensemble • THINKING ABOUT the culture, history, ideas and emo ons expressed through the music • MARVELING at the skill of the musicians • REFLECTING on the sounds and sights experienced at the theater. -

June 22, 2019

The PA Renaissance Faire Production is proud to sponsor the NAFC COMMISSION Member of the North American Feis Commission President: Jim Graven [email protected] Member of An Coimisiun, Dublin, Ireland Feis is sanctioned by and governed by An Comisiun (www.clrg.ie), the NAFC (www.northamericanfeiscommission.org) and the Mid-Atlantic Region (www.midatlanticregion.com) NAFC CHAMPIONSHIPS Edward Callaghan Music Scholarship Championship Under 15 - will be held at the Golden Horseshoe Feis on June 15, 2019 FEIS INFORMATION James Brennan Music Scholarship Championship Under 21 - will be held at the Peach State Feis on May 4, 2019 Saturday - June 22, 2019 NAFC Championship Belts Starting at 9:00 am! Sacramento, CA - January 19th, 2019 Gerry Campbell Senior Belt PA Renaissance Fairegrounds Robert Gabor Junior Belt 2775 Lebanon Rd. George Sweetnam Minor Belt Manheim, PA 17545 FEIS REGISTRATION SUMMARY Info: parenfaire.com Up to June 12, all registration only accepted at www.quickfeis.com Feis caps are: (registration will close for those levels only once that cap has been reached) o Grades ..................... 500 o Championship ......... 150 FEIS ADJUDICATORS Anne Marie Leonard, Canada Eileen McDonagh-Moore, New York Jimmy Early, New York Joan T. Cass, New York Chairman: Jim Graven Kathy Spencer-Revis, New York Treasurer: Carrie Emich Kerry Kelly Oster, New York Kristen Butke-Zagorski, Tennessee Entry Secretary: Kathleen Yates Laura Le Meusier, California Syllabus: Jim Graven Patricia Morissy, New York Peggy Woods Doherty, Massachusetts Siobhan Moore, New York COMPETITION FEES CELTIC FLING FEIS FESTIVAL Feis Admission includes ONE day ticket to the festival Competition Fees FEES (you can purchase a second day ticket at registration) Solo Dancing / TR / Sets / Non-Dance Kick-off concert on Friday featuring great performers! $ 10 Bring your appetite and enjoy delicious foods and (per competitor and per dance) refreshing wines, ales & ciders while listening to the live Preliminary Championship music! Gates open at 4PM. -

Scottish and Irish Elements of Appalachian Fiddle Music

Butler University Digital Commons @ Butler University Undergraduate Honors Thesis Collection Undergraduate Scholarship 3-1995 Scottish and Irish Elements of Appalachian Fiddle Music Matthew S. Emmick Butler University Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.butler.edu/ugtheses Part of the Ethnomusicology Commons, and the Musicology Commons Recommended Citation Emmick, Matthew S., "Scottish and Irish Elements of Appalachian Fiddle Music" (1995). Undergraduate Honors Thesis Collection. 21. https://digitalcommons.butler.edu/ugtheses/21 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Undergraduate Scholarship at Digital Commons @ Butler University. It has been accepted for inclusion in Undergraduate Honors Thesis Collection by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ Butler University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. BUTLER UNIVERSITY HONORS PROGRAM Honors Thesis Certification Matthew S. Emmick Applicant (Name as It Is to appear on dtplomo) Scottish and Irish Elements of Appalachian Fiddle M'-Isic Thesis title _ May, 1995 lnter'lded date of commencemenf _ Read and approved by: ' -4~, <~ /~.~~ Thesis adviser(s)/ /,J _ 3-,;13- [.> Date / / - ( /'--/----- --",,-..- Commltte~ ;'h~"'h=j.R C~.16b Honors t-,\- t'- ~/ Flrst~ ~ Date Second Reader Date Accepied and certified: JU).adr/tJ, _ 2111c<vt) Director DiJe For Honors Program use: Level of Honors conferred: University Magna Cum Laude Departmental Honors in Music and High Honors in Spanish Scottish and Irish Elements of Appalachian Fiddle Music A Thesis Presented to the Departmt!nt of Music Jordan College of Fine Arts and The Committee on Honors Butler University In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for Graduation Honors Matthew S. Emmick March, 24, 1995 -l _ -- -"-".,---. -

Barn Dance Square Dance Ceilidh Twmpath Contra Hoe Down 40'S

Paul Dance Caller and Teacher Have a look then get in touch [email protected] [email protected] Barn Dance 0845 643 2095 Local call rate from most land lines Square Dance (Easy level to Plus) Ceilidh Twmpath Contra Hoe Down 40’s Night THE PARTY EVERYONE CAN JOIN IN AND EVERYONE CAN ENJOY! So you are thinking of having a barn dance! Have you organised one before? If you haven't then the following may be of use to you. A barn dance is one of the only ways you can get everyone involved from the start. NO experience is needed to take part. Anyone from four to ninty four can join in. The only skill needed is being able to walk. All that is required is to be able to join hands in a line or a circle, link arms with another dancer, or join hands to make an arch. The rest is as easy as falling off a log. You dance in couples and depending on the type of dance you can dance in groups from two couples, four couples, and upwards to include the whole floor. You could be dancing in lines, in coloumns, in squares or in circles,. It depends on which dance the caller calls. The caller will walk everyone through the dance first so all the dancers know what the moves are. The caller will call out all the moves as you dance until the dancers can dance the dance on their own. A dance can last between 10 and 15 minutes including the walk through. -

Highland Dance Competitions & Championships

HIGHLAND DANCE COMPETITIONS & CHAMPIONSHIPS ScotDance USA MW-0202 May 22-24, 2020 Alma College Art Smith Arena – Hogan Center 614 West Superior Street Alma, Michigan 48801 EVENTS: Choreography Competition Great Lakes Open Championship Great Lakes Open Premiership Pre-Premier Competition Great Lakes Closed Championship – Midwest Regional Qualifier for USIR Judges: Pipers: Diane Krugh – Houston, Texas Glen Sinclair – London, Ontario Pat McMaster – Niagara-on-the-Lake, Ontario Bill Weaver – St. Louis, Michigan Jill Young – Calgary, Alberta Registration: Visit Ticketleap for registration information for all events. Sponsorship opportunities are also available. $5 from each entry goes to support ScotDance USA Midwest. Entries accepted through May 17, 2020, unless otherwise noted. Rules: 1. Competitions will be conducted in accordance with the rules of the Royal Scottish Official Board of Highland Dancing (RSOBHD). 2. The judge’s decision is final. 3. Age groups will be determined according to the number of entries and competitors’ ages as of the day of the competitions, with the exception of the Great Lakes Closed Championship. 4. Dancers must present their 2020 registration card to register and receive awards. 5. Dancers first to enter shall be last to dance. 6. Dancers must be ready and appear when called or forfeit the chance to dance. 7. Dancers must be in full costume to receive awards. 8. Awards are given at the judge’s discretion. 9. Alma Highland Festival reserves the right to make changes to the event or schedule so long as the change falls within the scope of RSOBHD Rules. Questions: Megan Brown, Organizer Email: [email protected] Phone/Text: (989) 763-6456 Friday, May 22, 2020: Choreography Competition Registration opens at 5:30pm, competition begins at 6:00pm. -

Frederick J. Lavigne Theater Orchestra Music 1878-1937 an Inventory of Holdings at the American Music Research Center

Frederick J. Lavigne Theater Orchestra Music 1878-1937 An inventory of holdings at the American Music Research Center American Music Research Center, University of Colorado at Boulder Frederick J. Lavigne Theater Orchestra Music1878-1937 Descriptive summary Title Frederick J. Lavigne theater orcehstra music Date(s) 1878-1937 ID COU-AMRC-101 Origination Lavigne, Frederick J. Repository The American Music Research Center University of Colorado at Boulder 288 UCB Boulder, CO 80309 Location Housed in the American Music Research Center Physical Description 126 boxes Scope and Contents The Frederick J. Lavigne Theater Orchestra Music collection contains 126 boxes of theater orchestra sheet music. The collection was addressed to Frederick J. Lavigne at the Stadium Theater in Woonsocket, Rhode Island. A majority of the pieces in this collection show Lavigne's full name stamped on the sheet music. Administrative Information Arrangement of Frederick J. Lavigne Theater Orchestra Music Collection is divided into one series of 126 boxes. The collection is arranged alphabetically by title of piece followed by composer and arranger. Dates of publication are also included in the listings. Access restrictions The collection is open for research. Publication Rights The American Music Research Center does not control rights to any material in this collection. Requests to publish any material in the collection should be directed to the copyright holders. Source of acquisition This collection was donated by Rodney Sauer in 2014 Preferred Citation [Identification of item], Frederick J. Lavigne Theater Orchestra Music, University of Colorado at Boulder - Page 2 - Frederick J. Lavigne Theater Orchestra Music1878-1937 Index Terms Access points related to this collection: Personal Names Lavigne, Frederick J. -

AN INTRODUCTION to the ARCHITECTURAL HERITAGE of COUNTY DONEGAL

AN INTRODUCTION TO THE ARCHITECTURAL HERITAGE of COUNTY DONEGAL AN INTRODUCTION TO THE ARCHITECTURAL HERITAGE of COUNTY DONEGAL COUNTY DONEGAL Mount Errigal viewed from Dunlewey. Foreword County Donegal has a rich architectural seventeenth-century Plantation of Ulster that heritage that covers a wide range of structures became a model of town planning throughout from country houses, churches and public the north of Ireland. Donegal’s legacy of buildings to vernacular houses and farm religious buildings is also of particular buildings. While impressive buildings are significance, which ranges from numerous readily appreciated for their architectural and early ecclesiastical sites, such as the important historical value, more modest structures are place of pilgrimage at Lough Derg, to the often overlooked and potentially lost without striking modern churches designed by Liam record. In the course of making the National McCormick. Inventory of Architectural Heritage (NIAH) The NIAH survey was carried out in phases survey of County Donegal, a large variety of between 2008 and 2011 and includes more building types has been identified and than 3,000 individual structures. The purpose recorded. In rural areas these include structures of the survey is to identify a representative as diverse as bridges, mills, thatched houses, selection of the architectural heritage of barns and outbuildings, gate piers and water Donegal, of which this Introduction highlights pumps; while in towns there are houses, only a small portion. The Inventory should not shopfronts and street furniture. be regarded as exhaustive and, over time, other A maritime county, Donegal also has a rich buildings and structures of merit may come to built heritage relating to the coast: piers, light. -

Highland & National Dancing

th PDANZ Morrinsville A & P Saturday 6 March 2021 South Auckland HIGHLAND & NATIONAL DANCING Approved To be conducted under the Rules of P & D Assn. of New Zealand (Inc) 31/1/2021 SPONSORED BY MORRINSVILLE FLOORING XTRA & BEDS R US MORRINSVILLE AUTO TRIM AND UPHOLSTERERS Place: The Morrinsville Recreation Grounds, Anzac Ave If wet at Morrinsville Soccer Club Rooms, Recreation Grounds CLOSING DATE: 25th February 2021 Entries to: Morrinsville A & P Society, P. O. Box 284 Morrinsville 3340 Enquires:-Phone 07 889 3831 email - [email protected] Time: 9 am Saturday 6th March 2021 Entry Fee: $4.00 per class. (incl Pipers Fee). Unless stated otherwise. Late entries accepted on the day at 50 cents extra, per class Prizes: Medals for 1st, 2nd & 3rd Novice, Restricted and all Under 10 yrs Under 12 & 14 Years -1st; $6 2nd; $5, 3rd; $4, - Under 16: 1st; $10 2nd; $8 3rd; $7. Merit Award -Money. Unless stated otherwise. Points Prize for each age group. JUDGE: - Tess Pilkington STEWARD: - Mrs Julie Lee Novice Under 12 years Class 1000 Novice Highland Fling Class 1013 Highland Fling (Will need more than 2 Dancers or it will be a display) Class 1014 Sword Dance Class 1015 Irish Jig Restricted Under 14 years (never won that dance) Class 1016 Sailors Hornpipe Class 1001 Highland Fling Class 1002 Sword Dance Under 14 years Class 1003 Irish Jig Class 1017 Highland Reel (Sub Sword) Class 1004 Sailors Hornpipe Class 1018 Sean Truibhas Class 1019 Irish Hornpipe Under 8 years Class 1020 Sailors Hornpipe Class 1005 Highland Fling Class 1006 Sword Dance