Cy Twombly's 'Ferragosto' Series

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Louise Lawler

Louise Lawler Louise Lawler was born in 1947 in Bronxville, New York. Lawler received her Birdcalls, 1972/1981 VITO ACCONCI audio recording and text, 7:01 minutes BFA in art from Cornell University, New York, in 1969, and moved to New York CARL ANDRE LeWitt Collection, Chester, CT City in 1970. Lawler held her first gallery show at Metro Pictures, New York, in RICHARD ARTSCHWAGER 1982. Soon after, Lawler gained international recognition for her photographic JOHN BALDESSARI ROBERT BARRY and installation-based projects. Her work has been featured in numerous interna- JOSEPH BEUYS tional exhibitions, including Documenta 12, Kassel, Germany (2007); the Whitney DANIEL BUREN Biennial, New York (1991, 2000, and 2008); and the Triennale di Milano (1999). SANDRO CHIA Solo exhibitions of her work have been organized at Portikus, Frankfurt (2003); FRANCESCO CLEMENTE the Museum für Gegenwartskunst, Basel, Switzerland (2004); the Wexner Center ENZO CUCCHI for the Arts, Ohio (2006); and Museum Ludwig, Germany (2013). In 2005, the GILBERT & GEORGE solo exhibition In and Out of Place: Louise Lawler and Andy Warhol was presented DAN GRAHAM at Dia:Beacon, which comprised a selection of photographs taken by Lawler, all HANS HAACKE of which include works by Warhol. She lives and works in New York City. NEIL JENNEY DONALD JUDD ANSELM KIEFER JOSEPH KOSUTH SOL LEWITT RICHARD LONG GORDON MATTA-CLARK MARIO MERZ SIGMAR POLKE GERHARD RICHTER ED RUSCHA JULIAN SCHNABEL CY TWOMBLY ANDY WARHOL LAWRENCE WEINER Louise Lawler Since the early 1970s, Louise Lawler has created works that expose the In 1981, Lawler decided to make an audiotape recording of her reading the economic and social conditions that affect the reception of art. -

Order Sons and Daughters of Italy in America Italian Festival Directory 2021

ORDER SONS AND DAUGHTERS OF ITALY IN AMERICA ITALIAN FESTIVAL DIRECTORY 2021 Compiled by: The Order Sons and Daughters of Italy in America 219 E Street N.E. Washington, DC 20002 Telephone: 202-547-2900 www.osia.org [email protected] THE ORDER SONS AND DAUGHTERS OF ITALY IN AMERICA 2021 ITALIAN FESTIVAL DIRECTORY This directory lists over 200 Italian festivals held in states around the country. The directory supplies each festival’s name, month, city, state and website. The directory was compiled by the Order Sons and Daughters of Italy in America (OSDIA). This directory is updated annually, but please be advised that there may be slight discrepancies due to availability of updated information provided The custom of honoring favorite saints with outdoor ceremonies was brought to America more than 100 years ago by the early Italian immigrants. The festivals vary in size and character. Some consist of only the saint’s statue, a band and a procession while others are colossal celebrations that last several days and include symphonic bands, entertainers, food stands, rides and fireworks. A familiar sight at most festivals is the saint’s statue covered with money or jewelry, later donated to the local church or saint’s society. The oldest festival is believed to be the Feast of Our Lady of Mount Carmel in Hammonton, NJ. The biggest festival is the Feast of San Gennaro held every September in New York City, which attracts about one million people. Large festivals can also be found in West Virginia (Wheeling’s Upper Ohio Valley Italian Heritage Festival in July and Clarksburg’s Italian Heritage Festival in September) and in Wisconsin (Milwaukee’s Festa Italiana in July), among others. -

Italy Travel and Driving Guide

Travel & Driving Guide Italy www.autoeurope. com 1-800-223-5555 Index Contents Page Tips and Road Signs in Italy 3 Driving Laws and Insurance for Italy 4 Road Signs, Tolls, driving 5 Requirements for Italy Car Rental FAQ’s 6-7 Italy Regions at a Glance 7 Touring Guides Rome Guide 8-9 Northwest Italy Guide 10-11 Northeast Italy Guide 12-13 Central Italy 14-16 Southern Italy 17-18 Sicily and Sardinia 19-20 Getting Into Italy 21 Accommodation 22 Climate, Language and Public Holidays 23 Health and Safety 24 Key Facts 25 Money and Mileage Chart 26 www.autoeurope.www.autoeurope.com com 1-800 -223-5555 Touring Italy By Car Italy is a dream holiday destination and an iconic country of Europe. The boot shape of Italy dips its toe into the Mediterranean Sea at the southern tip, has snow capped Alps at its northern end, and rolling hills, pristine beaches and bustling cities in between. Discover the ancient ruins, fine museums, magnificent artworks and incredible architecture around Italy, along with century old traditions, intriguing festivals and wonderful culture. Indulge in the fantastic cuisine in Italy in beautiful locations. With so much to see and do, a self drive holiday is the perfect way to see as much of Italy as you wish at your own pace. Italy has an excellent road and highway network that will allow you to enjoy all the famous sites, and give you the freedom to uncover some undiscovered treasures as well. This guide is aimed at the traveler that enjoys the independence and comfort of their own vehicle. -

Reading Cy Twombly: Poetry in Paint

INTRODUCTION: TWOMBLY’S BOOKS Bright books! the perspectives to our weak sights: The clearprojections of discerning lights, Burning and shining thoughts; man’s posthume day: Thetrack of dead souls, and their Milky- Way. — Henry Vaughan, “To His Books,” ll. 1– 41 Poetry is a centaur. The thinking word- arranging, clarifying faculty must move and leap with the energizing, sentient, musical faculties. —Ezra Pound, “The Serious Artist” (1913)2 The library that Cy Twombly left after his death, in his house at Gaeta by the Tyrrhenian Sea on the coast between Rome and Naples, included many volumes of literature, travel- books and— as one might expect— books about art and artists. His collection of poets is central to the subject of this book: Twombly’s use of poetic quotation and allusion as signature features of his visual practice.3 His collection of poetry included, among others, Sappho and the Greek Bronze Age poets; Theocritus and the Greek Bucolic poets; Ovid and Virgil; Horace and Catullus; Edmund Spenser and John Keats; Saint- John Perse and T. S. Eliot; Ezra Pound and Fernando Pessoa; C. P. Cavafy and George Seferis; Rainer Maria Rilke and Ingeborg Bachmann. Most if not all of these names will be familiar to viewers of Twombly’s work and to readers of art criticism about it. Unusually among painters of his— or indeed any— period, Twombly’s work includes not just names, titles, and phrases, but entire lines and passages of poetry, selected (and sometimes edited) as part of his distinctive aesthetic. Twombly’s untidy and erratic scrawl 1 job:油画天地 内文pxii 20160415 fang job:油画天地 内文p1 20160415 fang energizes his graphic practice. -

Italian Films (Updated April 2011)

Language Laboratory Film Collection Wagner College: Campus Hall 202 Italian Films (updated April 2011): Agata and the Storm/ Agata e la tempesta (2004) Silvio Soldini. Italy The pleasant life of middle-aged Agata (Licia Maglietta) -- owner of the most popular bookstore in town -- is turned topsy-turvy when she begins an uncertain affair with a man 13 years her junior (Claudio Santamaria). Meanwhile, life is equally turbulent for her brother, Gustavo (Emilio Solfrizzi), who discovers he was adopted and sets off to find his biological brother (Giuseppe Battiston) -- a married traveling salesman with a roving eye. Bicycle Thieves/ Ladri di biciclette (1948) Vittorio De Sica. Italy Widely considered a landmark Italian film, Vittorio De Sica's tale of a man who relies on his bicycle to do his job during Rome's post-World War II depression earned a special Oscar for its devastating power. The same day Antonio (Lamberto Maggiorani) gets his vehicle back from the pawnshop, someone steals it, prompting him to search the city in vain with his young son, Bruno (Enzo Staiola). Increasingly, he confronts a looming desperation. Big Deal on Madonna Street/ I soliti ignoti (1958) Mario Monicelli. Italy Director Mario Monicelli delivers this deft satire of the classic caper film Rififi, introducing a bungling group of amateurs -- including an ex-jockey (Carlo Pisacane), a former boxer (Vittorio Gassman) and an out-of-work photographer (Marcello Mastroianni). The crew plans a seemingly simple heist with a retired burglar (Totó), who serves as a consultant. But this Italian job is doomed from the start. Blow up (1966) Michelangelo Antonioni. -

An Artist of Selective Abandon by Roberta Smith New

The New York Times July 6, 2011 GAGOSIAN GALLERY AN APPRAISAL July 6, 2011 An Artist of Selective Abandon Cy Twombly with his 3,750-square-foot ceiling painting at the Louvre, commissioned for the Salle des Bronzes By ROBERTA SMITH With the death on Tuesday in Rome of Cy Twombly at the age of 83, postwar American painting has lost a towering and inspirational talent. Although he tended to be overshadowed by two of his closest colleagues — Robert Rauschenberg and Jasper Johns — Mr. Twombly played an equally significant role in opening pathways beyond the high-minded purity and frequent machismo of Abstract Expressionism, the dominant painting style in the late 1940s and ‘50s, when the three men entered the New York art world. In different ways each artist countered the Olympian loftiness of the Abstract Expressionists by stressing the loquacious, cosmopolitan nature of art and its connectedness not only to other forms of culture but also to the volatile machinations of the human mind and to lived experience. Rauschenberg’s art functioned as a kind of sieve in which he caught and brilliantly composed the chaotic flood of existing objects or images that the world offered. Mr. Johns, always more cerebral and introspective, isolated individual motifs like targets and flags, mystifying their familiarity with finely calibrated brushwork and collage. His methodical approach to art making helped set the stage for Conceptual Art and influenced generations of artists. Mr. Twombly worked with a combination of abandon and selectivity that split the difference between his two friends. His work was in many ways infinitely more basic, even primitive, in its emphasis on direct old-fashioned mark making, except that his feverish scribbles and calligraphic scrawls made that process seem new and electric. -

Art on the Texan Horizon

Set out on a fascinating journey through the desert of West Texas for an unforgettable stay in Marfa. Immerse yourself in the landscapes that inspired hundreds of brilliant sculptures and installations and learn more about the vibrant artistic community built by Donald Judd and his minimalist contemporaries. Wake up to beautiful sunrises and take in the dramatic sunsets as you explore the region. Compliment your adventures through the desert with a stay in Houston, Texas, a city with a wealth of Modern and Contemporary artwork and see fascinating works by artists such as Dan Flavin, Mark Rothko, and Cy Twombly. Join us for an enriching voyage to see remarkable contributions made by some Art on the of America’s greatest artists. Itinerary Overview* Texan Horizon TUESDAY, OCTOBER 29, 2019 MARFA & HOUSTON Arrivals October 29 – November 3, 2019 Fly to Midland airport, take a private group transfer to Marfa, and enjoy an enchanting welcome dinner. WEDNESDAY, OCTOBER 30, 2019 An Insider’s Marfa Begin the day at Donald Judd’s compound, which houses a collection of his works, follow a guided tour in downtown Marfa to learn more about the man who became this great figure of American Minimalism, and visit vibrant and eclectic local galleries. THURSDAY, OCTOBER 31, 2019 Conversations with Nature Take a scenic drive to the Chihuahuan Nature Center, enjoy breathtaking views of the mountains and rock formations of the area, walk through the Botanical Gardens, and have a lovely outdoor picnic in a beautiful setting. This afternoon, return to Marfa for a guided tour of the Chinati Foundation, including Donald Judd’s series of aluminum sculptures, Dan Flavin’s light installations, and Robert Irwin’s From Dawn to Dusk Special Experiences sunset experience. -

Il Piccolo Giornale August, 2018

Founded 1994 Il Piccolo Giornale August, 2018 Il Piccolo Giornale is the official newsletter of Club ItaloAmericano of Green Bay, Wi. Website: http://clubitaloamericano.org/ Facebook: Club Italaloamericano of Green Bay Board of Directors Send contributions/comments to: [email protected] Officers: President L. V. Teofilo Vice President Patrick Kloster Treasurer Vicky Sobeck Secretary Mary Prisco Past President FERRAGOSTO clude races such as the well-known es is piccione arrosto (roast pi- Richard Gollnick Palio di Siena on August 16th, fire- geon). Another holiday entre is By Mary Prisco works, parades, live music, and pollo ai peperoni (chicken stewed Directors Ferragosto is an Italian public holi- dancing (notably Rome’s city-wide with peppers). Side dishes might Ron Cattelan day celebrated on August 15, the dance party, the Gran Ballo di Fer- include pomodori al riso (tomatoes Dominic Del Bian- same day Roman Catholics cele- ragosto). stuffed with rice), and salads, such co. as panzanella (Tuscan bread salad). brate the Assumption of the Virgin The typical holiday meal for Ferra- Marlene Feira Typical desserts might be water- Mary into heaven. The name gosto is held at midday, and is Janice Galt comes from the Latin Feriae Augus- melon, gelo di melone / gelu di Lisa Iapalucci ti, the festivals of the Emperor muluna (Sicilian watermelon pud- ding), and biscotti or donuts fla- Mark Mariucci Augustus, holidays which date back vored with anise. Darrell Sobeck to 18 BC. The Feriae Augusti were Lynn Thompson held at the same time of year as Door County Road Trip other ancient Roman festivals which celebrated the harvest and By Mary Prisco Ambassador at offered a time of rest after months Large On the warm, sunny afternoon of of intense physical labor. -

Cy Twombly: Third Contemporary Artist Invited to Install a Permanent Work at the Louvre Artdaily March

Artdaily.org March 24, 2010 GAGOSIAN GALLERY Cy Twombly: Third Contemporary Artist Invited to Install a Permanent Work at the Louvre View of the The Louvre's large new gallery ceiling by Cy Twombly, known for his abstract paintings only the third contemporary artist given the honor of designing a permanent work for the museum, in Paris, Tuesday, March 23, 2010. (AP Photo/Christophe Ena.) PARIS.- Selected by a committee of international experts, Cy Twombly is the third contemporary artist invited to install a permanent work at the Louvre: a painted ceiling for the Salle des Bronzes. The permanent installation of 21st century works at the Louvre, the introduction of new elements in the décor and architecture of the palace, is the cornerstone of the museum’s policy relating to contemporary art. This type of ambitious endeavor is in keeping with the history of the palace, which has served since its creation as an ideal architectural canvas for commissions of painted and sculpted decoration projects. Prior to Cy Twombly, the Louvre’s commitment to living artists has resulted in invitations extended to Anselm Kiefer in 2007 and to François Morellet for an installation unveiled earlier in 2010, but these three artists also follow in the footsteps of a long line of predecessors including Le Brun, Delacroix, Ingres and, in the twentieth century, Georges Braque. Twombly’s painting will be showcased on the ceiling of one of the Louvre’s largest galleries, in one of the oldest sections of the museum. It is a work of monumental proportions, covering more than 350 square meters, its colossal size ably served by the painter’s breathtaking and unprecedented vision. -

The Poetics of Memory: Cy Twombly's Roses and Peony Blossom Paintings Justine Marie Mccullough

Florida State University Libraries Electronic Theses, Treatises and Dissertations The Graduate School 2011 The Poetics of Memory: Cy Twombly's Roses and Peony Blossom Paintings Justine Marie McCullough Follow this and additional works at the FSU Digital Library. For more information, please contact [email protected] THE FLORIDA STATE UNIVERSITY COLLEGE OF VISUAL ARTS, THEATRE AND DANCE THE POETICS OF MEMORY: CY TWOMBLY’S ROSES AND PEONY BLOSSOM PAINTINGS By JUSTINE MARIE MCCULLOUGH A Thesis submitted to the Department of Art History in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts Degree Awarded: Spring Semester, 2011 The members of the committee approve the thesis of Justine McCullough, defended on April 4, 2011. _______________________________________ Lauren S. Weingarden Professor Directing Thesis _______________________________________ Roald Nasgaard Committee Member _______________________________________ Adam Jolles Committee Member Approved: _____________________________________ Adam Jolles, Chair, Department of Art History _____________________________________ Sally E. McRorie, Dean, College of Visual Arts, Theatre and Dance m The Graduate School has verified and approved the above-named committee members ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS First I would like to acknowledge the members of my thesis committee, Drs. Lauren S. Weingarden, Roald Nasgaard, and Adam Jolles, without all of whom this thesis would not have been possible. I would like to recognize my thesis director, Dr. Lauren Weingarden, whose patience, encouragement, and thorough edits have kept me on track. I am thankful for her enthusiastic guidance of this project, her mentorship throughout my graduate studies, and her continuing support of my academic endeavors. Thanks are also in order to Dr. Michael Carrasco, for the useful thoughts and suggestions he shared with me as I began my research, and to Drs. -

Culturegramstm World Edition 2020 Italy (Italian Republic)

CultureGramsTM World Edition 2020 Italy (Italian Republic) Much of the West's civilization and culture stems from the BACKGROUND Italian Peninsula. The area's history dates back several thousand years; one of the first civilizations to flourish was Land and Climate that of the Etruscans, between the eighth and second centuries Italy, including the islands of Sardegna (Sardinia) and Sicilia BC. The Etruscans influenced mostly central Italy and, later, (Sicily), is slightly smaller than Norway and slightly larger the Roman Empire. Before the Romans became prominent, than the U.S. state of Arizona. It boasts a variety of natural Greek civilization dominated the south. Rome later adopted landscapes: from the alpine mountains in the north to the much of the Greek culture and became a major power after coastal lowlands in the south. Shaped like a boot, the country 300 BC as it expanded throughout the Mediterranean region. is generally mountainous. The Italian Alps run along the By the fifth century AD, the western Roman Empire had northern border, and the Appennini (Apennines) form a spine fallen to a number of invasions. The peninsula was then down the peninsula. Sicily and Sardinia are also rocky and divided into several separate political regions. In addition to mountainous. The “heel” and some coastal areas are flat. The local rulers, French, Spanish, and Austrian leaders governed Po River Basin, to the north, holds some of Italy's richest various parts of Italy. The Italian Peninsula was the center of farmland and most of its heavy industry. many artistic, cultural, and architectural revolutions, Italy surrounds two independent nations: San Marino and including the great Renaissance of the 15th and 16th Città del Vaticano (Vatican City, or Holy See). -

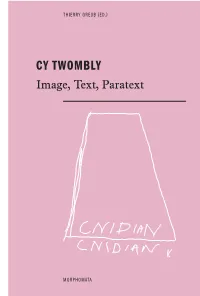

CY TWOMBLY Image, Text, Paratext

THIERRY GREUB (ED.) CY TWOMBLY Image, Text, Paratext MORPHOMATA The artworks of the US artist Cy Twombly (1928–2011) are considered to be hermetic and inaccessible. Pencil scribblings, explosions of paint, tumbling lines, over- lapping layers of color, and inscriptions, geometrical figures, numerals, rows of numbers, words, fragments of quotations, and enigmatic work-titles present very special challenges to both researchers and viewers. In the interdisciplinary and transcultural research meth- od of the Morphomata International Center for Advanced Studies at the University of Cologne, a conference was held in June 2012 that brought art historians together with renowned scholars of Egyptology, Archaeology, German, Greek, English, Japanese, and the Romance languages, i.e. all the fields and cultural spheres that were a source of inspiration for the œuvre of Cy Twombly. While these scholars inquire into the relation between title, work, and inscribed quotations, leading represen- tatives of research on Twombly focus on the visual lan- guage and scriptural-imagistic quality of Cy Twombly’s work. Through comprehensive interpretations of famous single works and groups in all the artistic media employed by Twombly, the volume’s cross-disciplinary view opens up a route into the associative-referential visual language of Cy Twombly. THIERRY GREUB (ED.) – CY TWOMBLY MORPHOMATA EDITED BY GÜNTER BLAMBERGER AND DIETRICH BOSCHUNG VOLUME 37 EDITED BY THIERRY GREUB CY TWOMBLY Image, Text, Paratext WILHELM FINK English edition translated from the German original: Cy Twombly. Bild, Text, Paratext (Morphomata, vol. 13). Paderborn 2014 (based on a conference held at the University of Cologne, 13–15 June 2012, by Morphomata International Center for Advanced Studies) Translated by Orla Mulholland, Daniel Mufson, Ehren Fordyce, and Timothy Murray Translated and printed with the generous support of the Cy Twombly Founda tion, Rome / New York and the Fondazione Nicola Del Roscio, Gaeta unter dem Förderkennzeichen 01UK1505.