Reading Cy Twombly: Poetry in Paint

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Dawn in Erewhon"

University of Pennsylvania ScholarlyCommons CUREJ - College Undergraduate Research Electronic Journal College of Arts and Sciences December 2007 Dimensions of Erewhon: The Modern Orpheus in Guy Davenport's "The Dawn in Erewhon" Patrick Dillon [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.upenn.edu/curej Recommended Citation Dillon, Patrick, "Dimensions of Erewhon: The Modern Orpheus in Guy Davenport's "The Dawn in Erewhon"" 10 December 2007. CUREJ: College Undergraduate Research Electronic Journal, University of Pennsylvania, https://repository.upenn.edu/curej/23. Revised version, posted 10 December 2007. This paper is posted at ScholarlyCommons. https://repository.upenn.edu/curej/23 For more information, please contact [email protected]. Dimensions of Erewhon: The Modern Orpheus in Guy Davenport's "The Dawn in Erewhon" Abstract In "The Dawn in Erewhon", the concluding novella of Tatlin!, Guy Davenport explores the myth of Orpheus in the context of two storylines: Adriaan van Hovendaal, a thinly veiled version of Ludwig Wittgenstein, and an updated retelling of Samuel Butler's utopian novel Erewhon. Davenport tells the story in a disjunctive style and uses the Orpheus myth as a symbol to refer to a creative sensibility that has been lost in modern technological civilization but is recoverable through art. Keywords Charles Bernstein, Bernstein, Charles, English, Guy Davenport, Davenport, Orpheus, Tatlin, Dawn in Erewhon, Erewhon, ludite, luditism Comments Revised version, posted 10 December 2007. This article is available at ScholarlyCommons: https://repository.upenn.edu/curej/23 Dimensions of Erewhon The Modern Orpheus in Guy Davenport’s “The Dawn in Erewhon” Patrick Dillon Introduction: The Assemblage Style Although Tatlin! is Guy Davenport’s first collection of fiction, it is the work of a fully mature artist. -

Guy Davenport's Literary Primitivism

National Library Bibliothèque nationale 1+1 of Canada du Canada Acquisitions and Direction des acquisitions el Bibliographie Services Branch des services bibliographiques 395 Wcllnglon Slreel 395. rue Wellington Ottawa. Onl.lfIQ Ollowo (Onlorio) KIA ON4 K1AON4 NOTICE AVIS The quality of this microform is La qualité de cette microforme heavily dependent upon the dépend grandement de la qualité quality of the original thesis de la thèse soumise au submitted for microfilming. microfilmage. Nous avons tout Every effort has been made to fait pour assurer une qualité ensure the highest quality of supérieure de reproduction. reproduction possible. If pages are missing, contact the S'il manque des pages, veuillez university which granted the communiquer avec l'université degree. qui a conféré le grade. Some pages may have indistinct La qualité d'impression de print especially if the original certaines pages peut laisser à pages were typed with a poor désirer, surtout si les pages typewriter ribbon or if the originales ont été university sent us an inferior dactylographiées à l'aide d'un photocopy. ruban usé ou si l'université nous a fait parvenir une photocopie de qualité inférieure. Reproduction in full or in part of La reproduction, même partielle, this microform is governed by de cette microforme est soumise the Canadian Copyright Act, à la Loi canadienne sur le droit R.S.C. 1970, c. C-30, and d'auteur, SRC 1970, c. C-30, et subsequent amendments. ses amendements subséquents. Canada '. GUY DAVENPORT'S LITERARY PRIMITIVISM séan A. Q'Reilly -

Louise Lawler

Louise Lawler Louise Lawler was born in 1947 in Bronxville, New York. Lawler received her Birdcalls, 1972/1981 VITO ACCONCI audio recording and text, 7:01 minutes BFA in art from Cornell University, New York, in 1969, and moved to New York CARL ANDRE LeWitt Collection, Chester, CT City in 1970. Lawler held her first gallery show at Metro Pictures, New York, in RICHARD ARTSCHWAGER 1982. Soon after, Lawler gained international recognition for her photographic JOHN BALDESSARI ROBERT BARRY and installation-based projects. Her work has been featured in numerous interna- JOSEPH BEUYS tional exhibitions, including Documenta 12, Kassel, Germany (2007); the Whitney DANIEL BUREN Biennial, New York (1991, 2000, and 2008); and the Triennale di Milano (1999). SANDRO CHIA Solo exhibitions of her work have been organized at Portikus, Frankfurt (2003); FRANCESCO CLEMENTE the Museum für Gegenwartskunst, Basel, Switzerland (2004); the Wexner Center ENZO CUCCHI for the Arts, Ohio (2006); and Museum Ludwig, Germany (2013). In 2005, the GILBERT & GEORGE solo exhibition In and Out of Place: Louise Lawler and Andy Warhol was presented DAN GRAHAM at Dia:Beacon, which comprised a selection of photographs taken by Lawler, all HANS HAACKE of which include works by Warhol. She lives and works in New York City. NEIL JENNEY DONALD JUDD ANSELM KIEFER JOSEPH KOSUTH SOL LEWITT RICHARD LONG GORDON MATTA-CLARK MARIO MERZ SIGMAR POLKE GERHARD RICHTER ED RUSCHA JULIAN SCHNABEL CY TWOMBLY ANDY WARHOL LAWRENCE WEINER Louise Lawler Since the early 1970s, Louise Lawler has created works that expose the In 1981, Lawler decided to make an audiotape recording of her reading the economic and social conditions that affect the reception of art. -

James S. Jaffe Rare Books Llc

JAMES S. JAFFE RARE BOOKS LLC P. O. Box 930 Deep River, CT 06417 Tel: 212-988-8042 Email: [email protected] Website: www.jamesjaffe.com Member Antiquarian Booksellers Association of America / International League of Antiquarian Booksellers All items are offered subject to prior sale. Libraries will be billed to suit their budgets. Digital images are available upon request. [ANTHOLOGY] JOYCE, James. Contact Collection of Contemporary Writers. (Edited by Robert McAlmon). 8vo, original printed wrappers. (Paris: Contact Editions Three Mountains Press, 1925). First edition, published jointly by McAlmon’s Contact Editions and William Bird’s Three Mountains Press. One of 300 copies printed in Dijon by Darantiere, who printed Joyce’s Ulysses. Slocum & Cahoon B7. With contributions by Djuna Barnes, Bryher, Mary Butts, Norman Douglas, Havelock Ellis, Ford Madox Ford, Wallace Gould, Ernest Hemingway, Marsden Hartley, H. D., John Herrman, Joyce, Mina Loy, Robert McAlmon, Ezra Pound, Dorothy Richardson, May Sinclair, Edith Sitwell, Gertrude Stein and William Carlos Williams. Includes Joyce’s “Work In Progress” from Finnegans Wake; Hemingway’s “Soldiers Home”, which first appeared in the American edition of In Our Time, Hanneman B3; and William Carlos Williams’ essay on Marianne Moore, Wallace B8. Front outer hinge cleanly split half- way up the book, not affecting integrity of the binding; bottom of spine slightly chipped, otherwise a bright clean copy. $2,250.00 BERRIGAN, Ted. The Sonnets. 4to, original pictorial wrappers, rebound in navy blue cloth with a red plastic title-label on spine. N. Y.: Published by Lorenz & Ellen Gude, 1964. First edition. Limited to 300 copies. A curious copy, one of Berrigan’s retained copies, presumably bound at his direction, and originally intended for Berrigan’s close friend and editor of this book, the poet Ron Padgett. -

An Artist of Selective Abandon by Roberta Smith New

The New York Times July 6, 2011 GAGOSIAN GALLERY AN APPRAISAL July 6, 2011 An Artist of Selective Abandon Cy Twombly with his 3,750-square-foot ceiling painting at the Louvre, commissioned for the Salle des Bronzes By ROBERTA SMITH With the death on Tuesday in Rome of Cy Twombly at the age of 83, postwar American painting has lost a towering and inspirational talent. Although he tended to be overshadowed by two of his closest colleagues — Robert Rauschenberg and Jasper Johns — Mr. Twombly played an equally significant role in opening pathways beyond the high-minded purity and frequent machismo of Abstract Expressionism, the dominant painting style in the late 1940s and ‘50s, when the three men entered the New York art world. In different ways each artist countered the Olympian loftiness of the Abstract Expressionists by stressing the loquacious, cosmopolitan nature of art and its connectedness not only to other forms of culture but also to the volatile machinations of the human mind and to lived experience. Rauschenberg’s art functioned as a kind of sieve in which he caught and brilliantly composed the chaotic flood of existing objects or images that the world offered. Mr. Johns, always more cerebral and introspective, isolated individual motifs like targets and flags, mystifying their familiarity with finely calibrated brushwork and collage. His methodical approach to art making helped set the stage for Conceptual Art and influenced generations of artists. Mr. Twombly worked with a combination of abandon and selectivity that split the difference between his two friends. His work was in many ways infinitely more basic, even primitive, in its emphasis on direct old-fashioned mark making, except that his feverish scribbles and calligraphic scrawls made that process seem new and electric. -

Art on the Texan Horizon

Set out on a fascinating journey through the desert of West Texas for an unforgettable stay in Marfa. Immerse yourself in the landscapes that inspired hundreds of brilliant sculptures and installations and learn more about the vibrant artistic community built by Donald Judd and his minimalist contemporaries. Wake up to beautiful sunrises and take in the dramatic sunsets as you explore the region. Compliment your adventures through the desert with a stay in Houston, Texas, a city with a wealth of Modern and Contemporary artwork and see fascinating works by artists such as Dan Flavin, Mark Rothko, and Cy Twombly. Join us for an enriching voyage to see remarkable contributions made by some Art on the of America’s greatest artists. Itinerary Overview* Texan Horizon TUESDAY, OCTOBER 29, 2019 MARFA & HOUSTON Arrivals October 29 – November 3, 2019 Fly to Midland airport, take a private group transfer to Marfa, and enjoy an enchanting welcome dinner. WEDNESDAY, OCTOBER 30, 2019 An Insider’s Marfa Begin the day at Donald Judd’s compound, which houses a collection of his works, follow a guided tour in downtown Marfa to learn more about the man who became this great figure of American Minimalism, and visit vibrant and eclectic local galleries. THURSDAY, OCTOBER 31, 2019 Conversations with Nature Take a scenic drive to the Chihuahuan Nature Center, enjoy breathtaking views of the mountains and rock formations of the area, walk through the Botanical Gardens, and have a lovely outdoor picnic in a beautiful setting. This afternoon, return to Marfa for a guided tour of the Chinati Foundation, including Donald Judd’s series of aluminum sculptures, Dan Flavin’s light installations, and Robert Irwin’s From Dawn to Dusk Special Experiences sunset experience. -

Writing Communities: Aesthetics, Politics, and Late Modernist Literary Consolidation

WRITING COMMUNITIES: AESTHETICS, POLITICS, AND LATE MODERNIST LITERARY CONSOLIDATION by Elspeth Egerton Healey A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy (English Language and Literature) in the University of Michigan 2008 Doctoral Committee: Associate Professor John A. Whittier-Ferguson, Chair Associate Professor Kali A. K. Israel Associate Professor Joshua L. Miller Assistant Professor Andrea Patricia Zemgulys © Elspeth Egerton Healey _____________________________________________________________________________ 2008 Acknowledgements I have been incredibly fortunate throughout my graduate career to work closely with the amazing faculty of the University of Michigan Department of English. I am grateful to Marjorie Levinson, Martha Vicinus, and George Bornstein for their inspiring courses and probing questions, all of which were integral in setting this project in motion. The members of my dissertation committee have been phenomenal in their willingness to give of their time and advice. Kali Israel’s expertise in the constructed representations of (auto)biographical genres has proven an invaluable asset, as has her enthusiasm and her historian’s eye for detail. Beginning with her early mentorship in the Modernisms Reading Group, Andrea Zemgulys has offered a compelling model of both nuanced scholarship and intellectual generosity. Joshua Miller’s amazing ability to extract the radiant gist from still inchoate thought has meant that I always left our meetings with a renewed sense of purpose. I owe the greatest debt of gratitude to my dissertation chair, John Whittier-Ferguson. His incisive readings, astute guidance, and ready laugh have helped to sustain this project from beginning to end. The life of a graduate student can sometimes be measured by bowls of ramen noodles and hours of grading. -

Cy Twombly: Third Contemporary Artist Invited to Install a Permanent Work at the Louvre Artdaily March

Artdaily.org March 24, 2010 GAGOSIAN GALLERY Cy Twombly: Third Contemporary Artist Invited to Install a Permanent Work at the Louvre View of the The Louvre's large new gallery ceiling by Cy Twombly, known for his abstract paintings only the third contemporary artist given the honor of designing a permanent work for the museum, in Paris, Tuesday, March 23, 2010. (AP Photo/Christophe Ena.) PARIS.- Selected by a committee of international experts, Cy Twombly is the third contemporary artist invited to install a permanent work at the Louvre: a painted ceiling for the Salle des Bronzes. The permanent installation of 21st century works at the Louvre, the introduction of new elements in the décor and architecture of the palace, is the cornerstone of the museum’s policy relating to contemporary art. This type of ambitious endeavor is in keeping with the history of the palace, which has served since its creation as an ideal architectural canvas for commissions of painted and sculpted decoration projects. Prior to Cy Twombly, the Louvre’s commitment to living artists has resulted in invitations extended to Anselm Kiefer in 2007 and to François Morellet for an installation unveiled earlier in 2010, but these three artists also follow in the footsteps of a long line of predecessors including Le Brun, Delacroix, Ingres and, in the twentieth century, Georges Braque. Twombly’s painting will be showcased on the ceiling of one of the Louvre’s largest galleries, in one of the oldest sections of the museum. It is a work of monumental proportions, covering more than 350 square meters, its colossal size ably served by the painter’s breathtaking and unprecedented vision. -

The Poetics of Memory: Cy Twombly's Roses and Peony Blossom Paintings Justine Marie Mccullough

Florida State University Libraries Electronic Theses, Treatises and Dissertations The Graduate School 2011 The Poetics of Memory: Cy Twombly's Roses and Peony Blossom Paintings Justine Marie McCullough Follow this and additional works at the FSU Digital Library. For more information, please contact [email protected] THE FLORIDA STATE UNIVERSITY COLLEGE OF VISUAL ARTS, THEATRE AND DANCE THE POETICS OF MEMORY: CY TWOMBLY’S ROSES AND PEONY BLOSSOM PAINTINGS By JUSTINE MARIE MCCULLOUGH A Thesis submitted to the Department of Art History in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts Degree Awarded: Spring Semester, 2011 The members of the committee approve the thesis of Justine McCullough, defended on April 4, 2011. _______________________________________ Lauren S. Weingarden Professor Directing Thesis _______________________________________ Roald Nasgaard Committee Member _______________________________________ Adam Jolles Committee Member Approved: _____________________________________ Adam Jolles, Chair, Department of Art History _____________________________________ Sally E. McRorie, Dean, College of Visual Arts, Theatre and Dance m The Graduate School has verified and approved the above-named committee members ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS First I would like to acknowledge the members of my thesis committee, Drs. Lauren S. Weingarden, Roald Nasgaard, and Adam Jolles, without all of whom this thesis would not have been possible. I would like to recognize my thesis director, Dr. Lauren Weingarden, whose patience, encouragement, and thorough edits have kept me on track. I am thankful for her enthusiastic guidance of this project, her mentorship throughout my graduate studies, and her continuing support of my academic endeavors. Thanks are also in order to Dr. Michael Carrasco, for the useful thoughts and suggestions he shared with me as I began my research, and to Drs. -

CY TWOMBLY Image, Text, Paratext

THIERRY GREUB (ED.) CY TWOMBLY Image, Text, Paratext MORPHOMATA The artworks of the US artist Cy Twombly (1928–2011) are considered to be hermetic and inaccessible. Pencil scribblings, explosions of paint, tumbling lines, over- lapping layers of color, and inscriptions, geometrical figures, numerals, rows of numbers, words, fragments of quotations, and enigmatic work-titles present very special challenges to both researchers and viewers. In the interdisciplinary and transcultural research meth- od of the Morphomata International Center for Advanced Studies at the University of Cologne, a conference was held in June 2012 that brought art historians together with renowned scholars of Egyptology, Archaeology, German, Greek, English, Japanese, and the Romance languages, i.e. all the fields and cultural spheres that were a source of inspiration for the œuvre of Cy Twombly. While these scholars inquire into the relation between title, work, and inscribed quotations, leading represen- tatives of research on Twombly focus on the visual lan- guage and scriptural-imagistic quality of Cy Twombly’s work. Through comprehensive interpretations of famous single works and groups in all the artistic media employed by Twombly, the volume’s cross-disciplinary view opens up a route into the associative-referential visual language of Cy Twombly. THIERRY GREUB (ED.) – CY TWOMBLY MORPHOMATA EDITED BY GÜNTER BLAMBERGER AND DIETRICH BOSCHUNG VOLUME 37 EDITED BY THIERRY GREUB CY TWOMBLY Image, Text, Paratext WILHELM FINK English edition translated from the German original: Cy Twombly. Bild, Text, Paratext (Morphomata, vol. 13). Paderborn 2014 (based on a conference held at the University of Cologne, 13–15 June 2012, by Morphomata International Center for Advanced Studies) Translated by Orla Mulholland, Daniel Mufson, Ehren Fordyce, and Timothy Murray Translated and printed with the generous support of the Cy Twombly Founda tion, Rome / New York and the Fondazione Nicola Del Roscio, Gaeta unter dem Förderkennzeichen 01UK1505. -

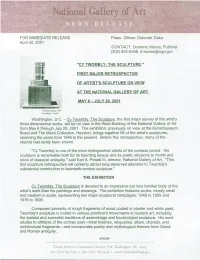

National Gallery of Art

National Gallery of Art FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE Press Officer: Deborah Ziska April 30, 2001 CONTACT: Domenic Morea, Publicist (202) 842-6358, [email protected] "CY TWOMBLY: THE SCULPTURE." FIRST MAJOR RETROSPECTIVE OF ARTIST'S SCULPTURE ON VIEW AT THE NATIONAL GALLERY OF ART. MAY 6-JULY 29. 2001 Unfitted, Rome. 1959 Kunsthaus. /uricli Washington, D.C. - Cv Twomblv: The Sculpture, the first major survey of the artist's three-dimensional works, will be on view in the West Building of the National Gallery of Art from May 6 through July 29, 2001. The exhibition, previously on view at the Kunstmuseum Basel and The Menil Collection, Houston, brings together 58 of the artist's sculptures, spanning the years from 1946 to the present. Before this retrospective, many of the objects had rarely been shown. "Cy Twombly is one of the most distinguished artists of the postwar period. His sculpture is remarkable both for its haunting beauty and its poetic allusions to motifs and relics of classical antiquity," said Earl A. Powell III, director, National Gallery of Art. "This first sculpture retrospective will certainly attract long-deserved attention to Twombly's substantial contribution to twentieth-century sculpture." THE EXHIBITION Cv Twombly: The Sculpture is devoted to an impressive but less familiar body of the artist's work than his paintings and drawings. The exhibition features works, mostly small and medium in scale, representing two major sculptural campaigns: 1948 to 1959 and 1976 to 1998. Composed primarily of rough fragments of wood coated in plaster and white paint, Twombly's sculpture is rooted in various prominent movements in modern art, including the dadaist and surrealist traditions of assemblage and found-object sculpture. -

DONALD JUDD Born 1928 in Excelsior Springs, Missouri

This document was updated January 6, 2021. For reference only and not for purposes of publication. For more information, please contact the gallery. DONALD JUDD Born 1928 in Excelsior Springs, Missouri. Died 1994 in New York City. SOLO EXHIBITIONS 1957 Don Judd, Panoras Gallery, New York, NY, June 24 – July 6, 1957. 1963–1964 Don Judd, Green Gallery, New York, NY, December 17, 1963 – January 11, 1964. 1966 Don Judd, Leo Castelli Gallery, 4 East 77th Street, New York, NY, February 5 – March 2, 1966. Donald Judd Visiting Artist, Hopkins Center Art Galleries, Dartmouth College, Hanover, NH, July 16 – August 9, 1966. 1968 Don Judd, The Whitney Museum of American Art, New York, NY, February 26 – March 24, 1968 [catalogue]. Don Judd, Irving Blum Gallery, Los Angeles, CA, May 7 – June 1, 1968. 1969 Don Judd, Leo Castelli Gallery, 4 East 77th Street, New York, NY, January 4 – 25, 1969. Don Judd: Structures, Galerie Ileana Sonnabend, Paris, France, May 6 – 29, 1969. New Works, Galerie Bischofberger, Zürich, Switzerland, May – June 1969. Don Judd, Galerie Rudolf Zwirner, Cologne, Germany, June 4 – 30, 1969. Donald Judd, Irving Blum Gallery, Los Angeles, CA, September 16 – November 1, 1969. 1970 Don Judd, Stedelijk Van Abbemuseum, Eindhoven, The Netherlands, January 16 – March 1, 1970; traveled to Folkwang Museum, Essen, Germany, April 11 – May 10, 1970; Kunstverein Hannover, Germany, June 20 – August 2, 1970; and Whitechapel Art Gallery, London, United Kingdom, September 29 – November 1, 1970 [catalogue]. Don Judd, The Helman Gallery, St. Louis, MO, April 3 – 29, 1970. Don Judd, Leo Castelli Gallery, 4 East 77th Street, and 108th Street Warehouse, New York, NY, April 11 – May 9, 1970.