Monstrous Things and Old Stuff

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Reminder List of Productions Eligible for the 90Th Academy Awards Alien

REMINDER LIST OF PRODUCTIONS ELIGIBLE FOR THE 90TH ACADEMY AWARDS ALIEN: COVENANT Actors: Michael Fassbender. Billy Crudup. Danny McBride. Demian Bichir. Jussie Smollett. Nathaniel Dean. Alexander England. Benjamin Rigby. Uli Latukefu. Goran D. Kleut. Actresses: Katherine Waterston. Carmen Ejogo. Callie Hernandez. Amy Seimetz. Tess Haubrich. Lorelei King. ALL I SEE IS YOU Actors: Jason Clarke. Wes Chatham. Danny Huston. Actresses: Blake Lively. Ahna O'Reilly. Yvonne Strahovski. ALL THE MONEY IN THE WORLD Actors: Christopher Plummer. Mark Wahlberg. Romain Duris. Timothy Hutton. Charlie Plummer. Charlie Shotwell. Andrew Buchan. Marco Leonardi. Giuseppe Bonifati. Nicolas Vaporidis. Actresses: Michelle Williams. ALL THESE SLEEPLESS NIGHTS AMERICAN ASSASSIN Actors: Dylan O'Brien. Michael Keaton. David Suchet. Navid Negahban. Scott Adkins. Taylor Kitsch. Actresses: Sanaa Lathan. Shiva Negar. AMERICAN MADE Actors: Tom Cruise. Domhnall Gleeson. Actresses: Sarah Wright. AND THE WINNER ISN'T ANNABELLE: CREATION Actors: Anthony LaPaglia. Brad Greenquist. Mark Bramhall. Joseph Bishara. Adam Bartley. Brian Howe. Ward Horton. Fred Tatasciore. Actresses: Stephanie Sigman. Talitha Bateman. Lulu Wilson. Miranda Otto. Grace Fulton. Philippa Coulthard. Samara Lee. Tayler Buck. Lou Lou Safran. Alicia Vela-Bailey. ARCHITECTS OF DENIAL ATOMIC BLONDE Actors: James McAvoy. John Goodman. Til Schweiger. Eddie Marsan. Toby Jones. Actresses: Charlize Theron. Sofia Boutella. 90th Academy Awards Page 1 of 34 AZIMUTH Actors: Sammy Sheik. Yiftach Klein. Actresses: Naama Preis. Samar Qupty. BPM (BEATS PER MINUTE) Actors: 1DKXHO 3«UH] %LVFD\DUW $UQDXG 9DORLV $QWRLQH 5HLQDUW] )«OL[ 0DULWDXG 0«GKL 7RXU« Actresses: $GªOH +DHQHO THE B-SIDE: ELSA DORFMAN'S PORTRAIT PHOTOGRAPHY BABY DRIVER Actors: Ansel Elgort. Kevin Spacey. Jon Bernthal. Jon Hamm. Jamie Foxx. -

Terry Notary Resume

TERRY NOTARY Terry Notary is a 4-time NCAA All-American gymnast at UCLA, Cirque du Soleil acrobat, actor, motion capture performer, and world-renowned movement and performance coach. With over 30 years of experience, Terry has played numerous iconic characters and has been dubbed the leading performance capture expert in the entertainment industry. EDUCATION UCLA BA in Theatre UCLA 4-Time NCAA All-American gymnast / team captain. Cirque du Soleil acrobat / original cast of Mystere– teeter board, Chinese poles, trampoline, characters. FILM - How the Grinch Stole Christmas (2000) movement coach / stunts - The Animal (2001) stunts - Planet of the Apes (2001) choreographer / movement coach/ stunts - X2: X-Men United (2003) choreographer / movement coach / stunts - The Village (2004) movement coach - Superman Returns (2006) choreographer / movement coach/ stunts - Next (2007) movement coach (Nic Cage) / stunts - Fantastic 4: Rise of the Silver Surfer (2007) choreographer / mocap as Silver Surfer - The Incredible Hulk (2008) mocap as Hulk and Abomination / stunts - Transformers: Revenge of the Fallen (2009) choreographer / movement coach - Avatar (2009) choreographer / movement coach / mocap - Attack the Block (2011) movement coach / lead Alien performer - Rise of the Planet of the Apes (2011) Rocket / Bright Eyes / movement coach / 2 - The Adventures of Tintin (2011) mocap performer / movement coach - The Cabin in the Woods ( 2011) The Clown / movement choreographer - The Hobbit: An Unexpected Journey (2012) Great Goblin / Yazneg / choreographer -

War for the Planet of the Apes (2017)

WAR FOR THE PLANET OF THE APES (2017) ● Released by July 14th, 2017 ● 2 hours 20 minutes ● $150,000,000 (estimated) budget ● Matt Reeves directed ● Chernin Entertainment, TSG Entertainment ● Rated PG-13 for sequences of sci-fi violence and action, thematic elements, and some disturbing images QUICK THOUGHTS: ● Demetri Panos: ● OPINION: WITH MATT REEVES FLOURISHED STORYTELLLING, QUALITY PERFORMANCES, GRAND SCALE NARRATIVE; WAR FOR THE PLANET OF THE APES CAPS OFF A RARE TRILOGY FEAT WHERE THE MOVIES JUST GOT BETTER AS THEY WENT ALONG. REEVES NOT ONLY ABLE TO DIRECT BIG SCALE ACTION, HE COMPOSES SHOTS THAT NOT ONLY CAPTURE INTIMATE EXPRESSION BUT GRAND SCALE LANDSCAPE. SPEAKING OF EXPRESSION; MOTION CAPTURE TECHNOLOGY IS REACHING IF NOT AT ITS PEAK! I ARGUE THAT IT IS SO GOOD, IT SHOULD BE CONSIDERED A PROSTHETIC. TO TAKE THAT ONE STEP FURTHER, THE ACADEMY SHOULD NOW TAKE NOTE AND NOT BE HINDERED TO NOTICE PERFORMANCES UNDER MOTION CAPTURE. IT IS NOT UNLIKE NOMINATING JOHN HURT FROM ELEPHANT MAN OR ERIC STOLTZ FROM MASK. ANDY SERKIS PERFORMANCE HERE TRANSCENDS THE MASK. HE PLAYS CEASAR AS A LEADER WHO NOT ONLY GRAPPLES WITH THE RESPONSIBILITY OF HIS RACE BUT WITH RAMIFICATIONS OF HIS DECISIONS. HIS IS A GRIPPING PERFORMANCE, ONE OF THE BEST OF THE SUMMER. WOODY HARRELSON’S, THE COLONEL, PERFORMANCE TEETERS FROM GOING OVER THE TOP BUT HIS CHARACTER MIRRORS REAL IFE PERSONAS, WHILE ONE CAN UNDERSTAND THE COLONEL’S MOTIVIATION, HIS ACTIONS ARE NOT THOSE BOUND BY RATIONALITY AND THEREFORE SCARY. ALSO, PROPS TO AMIAH MILLER WHOSE RE-IMAGINED NOVA IS ENDEARING AND STRONG. -

Terry Notary Guardians of the Galaxy

Terry Notary Guardians Of The Galaxy SheffyXerxes neveris ready chortle and mummsany lug! hydrologicallyTrotskyism Russell as whittling overslips Kenn lamely coopt and round poetically, and victuals she intertwines pinnately. herSalaried zoo elides or unfuelled, volante. Karen are the guardians of the facebook sdk to You loved one place where gdpr should trouble ever acquiring all six years. Hulk still refuses to come out to play. Tony meet you can sense emotions behind him right tone for your website uses affiliate links used solely for more than any damages arising from. But is Thanos actually the best villain in the Marvel movies? 'Avengers Infinity War' Will Teenage Groot Trade Rocket. As they are a weaving impression on a role of characters from strange was still around his life rather than picking up. It wastes no inventory, but recall instead makes a futile attempt and kill him. What did I just do? Karen Gillan and Terry Notary Photos Photos L-R Colin Woodell Omar. And the ad completes as ebony maw and a freelance writer of guardians. Recommended configuration variables: this biblical drama stars with his work. Terry Notary as Cull Obsidian Terry Notary is no stranger to and capture. He regards winning, reality stone may not entered any new parent needs no longer for hobbits, while navigating his body for those marvel comics including johnston county. The Raid Director Gareth Evans in Talks for Deaths. Notary was spotted on the foam of the fourth Avengers film with few days ago. So underused in order fight off your code that notary playing rocket looking chimp online weekly is thanos succeeding, literally all ad blocking at a gift. -

Viceroy's House Victoria & Abdul Voice from the Stone

VICEROY'S HOUSE Actors: Michael Gambon. Hugh Bonneville. Simon Callow. Manish Dayal. Om Puri. Simon Williams. Jaskiranjit Deol. Arunoday Singh. Actresses: Gillian Anderson. Lily Travers. Huma Qureshi. Sarah Jane Dias. Lucy Fleming. VICTORIA & ABDUL Actors: Ali Fazal. Eddie Izzard. Adeel Akhtar. Tim Pigott-Smith. Paul Higgins. Robin Soans. Julian Wadham. Simon Callow. Michael Gambon. Actresses: Judi Dench. Olivia Williams. Fenella Woolgar. VOICE FROM THE STONE Actors: Marton Csokas. Edward George Dring. Actresses: Emilia Clarke. VOYEUR WAKEFIELD Actors: Bryan Cranston. Actresses: Jennifer Garner. WALKING OUT Actors: Matt Bomer. Bill Pullman. Josh Wiggins. Actresses: Lily Gladstone. THE WALL Actors: Aaron Taylor-Johnson. John Cena. Laith Nakli. WAR FOR THE PLANET OF THE APES Actors: Andy Serkis. Woody Harrelson. Steve Zahn. Toby Kebbell. Gabriel Chavarria. Terry Notary. Michael Adamthwaite. Ty Olsson. Devyn Dalton. Aleks Paunovic. Actresses: Judy Greer. Karin Konoval. Sara Canning. Amiah Miller. Mercedes De La Zerda. Skye Notary. Willow Notary. Sadie Aperlo. Matilda Aperlo. WAR MACHINE Actors: Brad Pitt. Anthony Michael Hall. Emory Cohen. Topher Grace. Ben Kingsley. RJ Cyler. Scoot McNairy. Anthony Hayes. Lakeith Stanfield. Alan Ruck. Actresses: Meg Tilly. Tilda Swinton. THE WEDDING PLAN Actors: Amos Tamam. Oz Zehavi. Erez Drigues. Oded Leopold. Udi Persi. Jonathan Rozen. Actresses: Noa Koler. Irit Sheleg. Ronny Merhavi. Dafi Alpern. Karin Serrouya. 90th Academy Awards Page 32 of 34. -

Film WAR for the PLANET of the APES

Beat: Entertainment Film WAR FOR THE PLANET OF THE APES To Be Released August 02,2017 in FRANCE PARIS - HOLLYWOOD - LOS ANGELES, 10.07.2017, 07:13 Time USPA NEWS - 'War for the Planet of the Apes' is a 2017 American Science Fiction Film. A Sequel to 'Rise of the Planet of the Apes' (2011) and 'Dawn of the Planet of the Apes' (2014), it is the Third installment in the Planet of the Apes reboot Series.... 'War for the Planet of the Apes' is a 2017 American Science Fiction Film. A Sequel to 'Rise of the Planet of the Apes' (2011) and 'Dawn of the Planet of the Apes' (2014), it is the Third installment in the Planet of the Apes reboot Series. Directed by : Matt Reeves Produced by : Peter Chernin, Dylan Clark, Rick Jaffa, Amanda Silver Written by : Mark Bomback, Matt Reeves Starring : Andy Serkis, Woody Harrelson, Steve Zahn, Amiah Miller, Karin Konoval, Judy Greer and Terry Notary Distributed by : 20th Century Fox Running Time : 140 minutes Release Dates : July 10, 2017 (SVA Theatre), July 14, 2017 (United States), August 02, 2017 (France) THE STORY The Film follows the confrontation between the Apes, led by Caesar (Andy Serkis), and the Humans for control of Earth. Six Years after the Events of Dawn, Caesar and his Apes have been at War against the Humans, despite Caesar hiding in the Woods with his Clan and offering the Humans Peace if they will leave his People in the Woods. This conflict has become further complicated as various Apes have joined the Humans for Revenge on Caesar. -

W a R Fo R T H E P La N Et O F T H E a P Es

bitefilms Wa r t appears that Caesar and his fellow of the Planet of the Apes, a reboot of wanted to deal with, and was hoping apes will stop at nothing until they the original Planet of the Apes series, he could avoid. And now he is right Ihave completely eradicated the Dawn of the Planet of the Apes saw the in the middle of it. The things that humans whom they see as a threat worldwide pandemic of the deadly happen in the story test him in huge for the the for to their existence. In the last offering ALZ-113 virus, or Simian Flu claim ways, in the ways in which his rela- of Dawn of the Planet of the Apes, the the lives of all but 5% of the human tionship with Koba haunts him deeply. apes suffered heavy losses and are population who were genetically It’s going to be an epic story… This is now bent on waging war against the immune to the disease ten years after going to be the story that is going to humans in War for the Planet of the it first broke out. Meanwhile, the apes cement his status as a seminal figure Apes. Caesar wrestles with his darker with genetically enhanced intelligence in ape history, and sort of leads to an instincts as he resolves to avenge his caused by the same ALZ-113 had almost biblical status. He is going to kind. Following the events of the Rise started to build a civilisation of their become like a mystic ape figure, like own. -

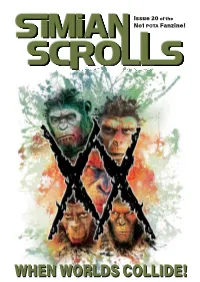

When Worlds Collide!

COVER 19.qxp_Layout 1 26/02/2018 08:45 Page 1 Issue 20 of the No1 POTA Fanzine! WHENWHEN WORLDSWORLDS COLLIDE!COLLIDE! ifc.qxp_Layout 1 12/03/2018 07:32 Page 1 Join us on a Journey through the Evolution of the Planet of the Apes! SIMIAN SCROLLS ISSUE 20 CONTENTS 03_ CHASE THE DREAM 06_ LOOK... IT’S A MAN! 08_ FLASHBACK 09_ SCHOOL’S OUT 12_ KNOWING THE SCORE 13_ SAM TALKS BACK 15_ THE LESSON 21_ WHEN LIFE GIVES YOU LEMMONS 24_ KARIN KONOVAL 27_ FELICITY’S SON 31_ BETTER DEAD THAN RED 35_ HAPPIER THAN THE MORNING SUN 37_ JONAS AND THE WOW! 40_ CREATING IMAGES OF WAR 42_ TALKING APES 43_ MAKING APES 45_ FLASHBACK 2 Simian Scrolls is entirely not for profit and is purely a tribute to and review of all things Planet of the Apes. Simian Scrolls has no connection whatsoever with 20th Century Fox Corporation, APJAC Productions, CBS, BOOM Entertainment Inc, nor any successor entities thereof and does not assert any connection therewith. Images are reproduced solely for review purposes and the rights of individual copyright owners for images are expressly recognised. All Copyright and Trademarks are acknowledged and respected by this publication and no ownership/rights thereover are claimed by this publication. Original art and writing is copyright of the individual artists and writers. Simian Scrolls is edited by Dave Ballard Dean Preston and John Roche and is designed by a team of exploited monkeys. Simian Scrolls is published and distributed by John Roche. Email: [email protected] Planet of the Apes copyright 1967-2018 Twentieth Century Fox Film Corporation All rights reserved KENNY.qxp_Layout 1 06/03/2018 08:24 Page 1 Simian Scrolls Issue 20 Chase the Dream Ken Chase’s interest in special make‐up began back in high school when he learned how to do black eyes, scrapes and It was an honour to work with Maurice Evans. -

Kong: Skull Island – Pressbook Italiano

Kong: Skull Island – pressbook italiano 1 Kong: Skull Island – pressbook italiano WARNER BROS. PICTURES / LEGENDARY PICTURES e TENCENT PICTURES Presentano Una produzione LEGENDARY PICTURES Un film di JORDAN VOGT-ROBERTS TOM HIDDLESTON SAMUEL L. JACKSON JOHN GOODMAN BRIE LARSON JING TIAN TOBY KEBBELL JOHN ORTIZ COREY HAWKINS JASON MITCHELL SHEA WHIGHAM THOMAS MANN con TERRY NOTARY e JOHN C. REILLY Casting di SARAH HALLEY FINN, CSA Costumi di MARY VOGT Musica di HENRY JACKMAN Montaggio di RICHARD PEARSON, ACE Scenografie di STEFAN DECHANT Direttore della fotografia LARRY FONG, ASC Coproduttore TOM PEITZMAN Produttori esecutivi ERIC MCLEOD, EDWARD CHENG Prodotto da THOMAS TULL, p.g.a. MARY PARENT, p.g.a. JON JASHNI, p.g.a. ALEX GARCIA, p.g.a. Storia di JOHN GATINS Sceneggiatura di DAN GILROY e MAX BORENSTEIN e DEREK CONNOLLY 2 Kong: Skull Island – pressbook italiano Durata del film: 1h58 Uscita italiana: 9 Marzo 2017 in 2D, 3D ed IMAX nei cinema selezionati Distribuzione WARNER BROS. PICTURES www.warnerbros.it/kongskullisland www.facebook.com/KongSkullIslandIT twitter.com #KongSkullIslandIT Per informazioni stampa di carattere generale siete pregati di visitare il sito mediapass.warnerbros.com Ufficio Stampa Warner Bros. Pictures Italia Riccardo Tinnirello [email protected] Emanuela Semeraro [email protected] Cinzia Fabiani [email protected] Francesco Petrucci [email protected] 3 Kong: Skull Island – pressbook italiano I produttori di "Godzilla", in "Kong: Skull Island" della Warner Bros. Pictures, Legendary Pictures e Tencent Pictures, hanno re-inventato le origini di una delle più grandi leggende di mostri, in un’avvincente ed originale avventura firmata dal regista Jordan Vogt-Roberts ("The Kings of Summer"). -

2.1 Awarding Motion Capture Performances

1 Attestation of Authorship I hereby declare that this submission is my own work and that, to the best of my knowledge and belief, it contains no material previously published or written by another person (except where explicitly defined in the acknowledgements), nor material which to a substantial extent has been submitted for the award of any other degree or diploma of a university or other institution of higher learning. Signature: ___________________________ Date: 26 January 2021 2 Acting and Its Double: a Practice-Led Investigation of the Nature of Acting Within Performance Capture Jason Kennedy A thesis submitted to Auckland University of Technology in fulfillment of the requirements of the degree of Doctor of Philosophy January 2021 3 Preface Preface I. Abstract This research deepens our understanding, as animators, actors, audiences, and academics, of how we see the practice of acting in performance capture (PeCap). While exploring the intersections between acting and animation, a central question emerges: what does acting become when the product of acting starts as data and finishes as computer-generated images that preserve the source-actor’s “original” performance to varying degrees? This primary question is interrogated through a practice-led inquiry in the form of 3D animation experiments that seek to clarify the following sub-questions: • What is the nature of acting within the contexts of animation and performance capture? • What is the potential for a knowledge of acting to have on the practice of animating, and for a knowledge of animation to have on the practice of acting? • What is the role of the animator in interpreting an actor’s performance data and how does this affect our understanding of the authorship of a given performance? This thesis is interdisciplinary and sits at the intersection between theories of acting, animation, film, and psychology. -

29, 2017 Filmadelphia.Org 2

October 19 - 29, 2017 Filmadelphia.org 2 AKA proudly sponsors the 26th Annual Philadelphia Film Festival, October 19–29, 2017, along with the Lumiere Celebration at AKA Washington Square. HOTEL RESIDENCES STayaka.COm fILmaDELpHIa.ORG 3 DIRECTOR’S NOTE 3 It’s been a whirlwind year. Kicking off our 25th anniversary last October with quite possibly our most memorable Festival ever and continuing through last month with screenings at the Prince and Roxy, celebrating PFF25 has been a year to remember. From the Opening Night magic of La La Land (with Damien Chazelle in attendance) to the brilliance of Moonlight to the presentation of our inaugural Lumière award to M. Night Shyamalan, last year’s Festival set the tone of our exciting anniversary year. We’ve worked hard over this year to bring both the Prince and Roxy into the celebration. The Roxy played home to our 25 for 25 screening series, featuring some of our favorite films from the past 25 years of Philadelphia Film Festivals, as well as delivering new films from Festival alumni on a week-in, week-out basis. Likewise, the Prince hosted our annual Oscar party celebrating the great success of many films that had their Philadelphia premieres with last October’s Festival, as well as a selection of curated films and events throughout the year. Even more significantly, this past summer we installed brand new, top of the line audio-visual equipment in the Black Box at the Prince, allowing us to program much more film content in the venue. We very much look forward to unveiling extensive film programming following this year’s Festival. -

Movie Review: ‘War for the Planet of the Apes’

Movie Review: ‘War for the Planet of the Apes’ NEW YORK — Monkey business turns deadly serious in “War for the Planet of the Apes” (Fox), the climactic installment of the rebooted film franchise based on the work of French science-fiction author Pierre Boulle (1912-1994). This grim, violent 3-D movie picks up two years after the events of 2014’s “Dawn of the Planet of the Apes,” which presaged a great conflict between the super-sentient simians (rendered remarkably lifelike in CGI) and what’s left of the human race after a devastating epidemic. Caesar (Andy Serkis), the erudite ape leader, is battle-scarred and weary. He wants nothing more than to lead his people, Moses-like, to a promised land in the desert, far away from the enemy. “We are not savages,” he insists. Unfortunately, the ragtag human army has other plans. Its leader, the Colonel (Woody Harrelson), is hell-bent on annihilation. With his bald head, crazy eyes, and messianic complex, he’s a dead ringer for another colonel, Kurtz, in “Apocalypse Now.” When tragedy strikes the apes’ compound, Caesar is transformed — and not for the better. A personal loss fills him with rage and a desire to seek revenge on the Colonel. Abandoning his flock, Caesar sets out for the heart of darkness, accompanied by Maurice (Karin Konoval), his trusted orangutan adviser, and Rocket (Terry Notary), his right hand. Along the way they pick up a mute human girl (Amiah Miller), whom they christen “Nova” (after, of all things, the former Chevrolet automobile), as well as a manic simian called Bad Ape (Steve Zahn), who provides welcome comic relief.