Reference Guide on Ex-Post Evaluation of Competition Agencies’ Enforcement Decisions

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Austrian Market for Mobile Telecommunication Services to Private Customers

The Austrian Market for Mobile Telecommunication Services to Private Customers An Ex-post Evaluation of the Mergers H3G/Orange and TA/Yesss! Sectoral Inquiry BWB/AW-393 Final Report Vienna, March 2016 cite as BWB (2016). The Austrian Market for Mobile Telecommunication Services to Pri- vate Customers. An Ex-post Evaluation of the Mergers H3G/Orange and TA/Yesss!, Sectoral Inquiry BWB/AW-393, Final Report, Vienna. BWB (2016). Der österreichische Privatkundenmarkt für Mobiltelefonie. Eine Ex- post Evaluierung der Zusammenschlüsse H3G/Orange und TA/Yesss!, Branchen- untersuchung BWB/AW-393, Endbericht (en), Wien. Authors Dominik Erharter Johannes Gruber Bundeswettbewerbsbehörde (BWB) Federal Competition Authority Praterstraße 31 (Galaxy Tower) 1020 Vienna, Austria T: +43 (0)1 245 08 - 0 F: +43 (0)1 587 42 00 E: [email protected] W: http://www.bwb.gv.at - 2 - Zusammenfassung Die Bundeswettbewerbsbehörde (BWB) kann allgemeine Untersuchungen eines Wirtschaftszweiges durchführen, sofern die Umstände vermuten lassen, dass der Wettbewerb in dem betreffenden Wirtschaftszweig eingeschränkt oder verfälscht ist. Im Rahmen einer solchen Branchenuntersuchung hat die BWB die Entwicklung des österreichischen Mobilfunkmarktes untersucht. Im Dezember 2012 wurde die Übernahme von Orange Austria (Orange) durch Hutchinson 3G Austria (H3G) von der Europäischen Kommission unter Auflagen freigegeben. In einer wirtschaftlich verbundenen Transaktion verkaufte H3G die zu Orange gehörende Marke "Yesss!" an den marktführenden Mobilfunkanbieter Telekom Austria (TA). Dieser Zusam- menschluss wurde im November 2012 vom österreichischen Kartellgericht ohne Auflagen freigegeben. Die BWB hatte sich in beiden Verfahren, vor dem Kartellge- richt und vor der Europäischen Kommission, gegen eine Freigabe ausgesprochen. Vor den Zusammenschlüssen gab es vier Mobilfunknetzbetreiber am österreichi- schen Markt. -

Merger Control Review

Merger Control Review Ninth Edition Editor Ilene Knable Gotts lawreviews © 2018 Law Business Research Ltd Merger Control Review Ninth Edition Editor Ilene Knable Gotts lawreviews © 2018 Law Business Research Ltd PUBLISHER Tom Barnes SENIOR BUSINESS DEVELOPMENT MANAGER Nick Barette BUSINESS DEVELOPMENT MANAGERS Thomas Lee, Joel Woods SENIOR ACCOUNT MANAGER Pere Aspinall ACCOUNT MANAGERS Sophie Emberson, Jack Bagnall PRODUCT MARKETING EXECUTIVE Rebecca Mogridge EDITORIAL COORDINATOR Gavin Jordan HEAD OF PRODUCTION Adam Myers PRODUCTION EDITOR Anna Andreoli SUBEDITOR Janina Godowska CHIEF EXECUTIVE OFFICER Paul Howarth Published in the United Kingdom by Law Business Research Ltd, London 87 Lancaster Road, London, W11 1QQ, UK © 2018 Law Business Research Ltd www.TheLawReviews.co.uk No photocopying: copyright licences do not apply. The information provided in this publication is general and may not apply in a specific situation, nor does it necessarily represent the views of authors’ firms or their clients. Legal advice should always be sought before taking any legal action based on the information provided. The publishers accept no responsibility for any acts or omissions contained herein. Although the information provided is accurate as of July 2018, be advised that this is a developing area. Enquiries concerning reproduction should be sent to Law Business Research, at the address above. Enquiries concerning editorial content should be directed to the Publisher – [email protected] ISBN 978-1-912228-46-1 Printed in Great Britain by -

An Evaluation of the Hutchison/Orange Merger in Austria

A Service of Leibniz-Informationszentrum econstor Wirtschaft Leibniz Information Centre Make Your Publications Visible. zbw for Economics Pedrós, Xavier; Bahia, Kalvin; Castells, Pau; Abate, Serafino Conference Paper Assessing the impact of mobile consolidation on innovation and quality: An evaluation of the Hutchison/Orange merger in Austria 28th European Regional Conference of the International Telecommunications Society (ITS): "Competition and Regulation in the Information Age", Passau, Germany, 30th July - 2nd August, 2017 Provided in Cooperation with: International Telecommunications Society (ITS) Suggested Citation: Pedrós, Xavier; Bahia, Kalvin; Castells, Pau; Abate, Serafino (2017) : Assessing the impact of mobile consolidation on innovation and quality: An evaluation of the Hutchison/Orange merger in Austria, 28th European Regional Conference of the International Telecommunications Society (ITS): "Competition and Regulation in the Information Age", Passau, Germany, 30th July - 2nd August, 2017, International Telecommunications Society (ITS), Calgary This Version is available at: http://hdl.handle.net/10419/169453 Standard-Nutzungsbedingungen: Terms of use: Die Dokumente auf EconStor dürfen zu eigenen wissenschaftlichen Documents in EconStor may be saved and copied for your Zwecken und zum Privatgebrauch gespeichert und kopiert werden. personal and scholarly purposes. Sie dürfen die Dokumente nicht für öffentliche oder kommerzielle You are not to copy documents for public or commercial Zwecke vervielfältigen, öffentlich ausstellen, -

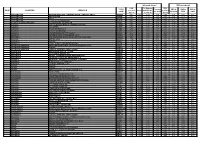

ZONE COUNTRIES OPERATOR TADIG CODE Calls

Calls made abroad SMS sent abroad Calls To Belgium SMS TADIG To zones SMS to SMS to SMS to ZONE COUNTRIES OPERATOR received Local and Europe received CODE 2,3 and 4 Belgium EUR ROW abroad (= zone1) abroad 3 AFGHANISTAN AFGHAN WIRELESS COMMUNICATION COMPANY 'AWCC' AFGAW 0,91 0,99 2,27 2,89 0,00 0,41 0,62 0,62 3 AFGHANISTAN AREEBA MTN AFGAR 0,91 0,99 2,27 2,89 0,00 0,41 0,62 0,62 3 AFGHANISTAN TDCA AFGTD 0,91 0,99 2,27 2,89 0,00 0,41 0,62 0,62 3 AFGHANISTAN ETISALAT AFGHANISTAN AFGEA 0,91 0,99 2,27 2,89 0,00 0,41 0,62 0,62 1 ALANDS ISLANDS (FINLAND) ALANDS MOBILTELEFON AB FINAM 0,08 0,29 0,29 2,07 0,00 0,09 0,09 0,54 2 ALBANIA AMC (ALBANIAN MOBILE COMMUNICATIONS) ALBAM 0,74 0,91 1,65 2,27 0,00 0,41 0,62 0,62 2 ALBANIA VODAFONE ALBVF 0,74 0,91 1,65 2,27 0,00 0,41 0,62 0,62 2 ALBANIA EAGLE MOBILE SH.A ALBEM 0,74 0,91 1,65 2,27 0,00 0,41 0,62 0,62 2 ALGERIA DJEZZY (ORASCOM) DZAOT 0,74 0,91 1,65 2,27 0,00 0,41 0,62 0,62 2 ALGERIA ATM (MOBILIS) (EX-PTT Algeria) DZAA1 0,74 0,91 1,65 2,27 0,00 0,41 0,62 0,62 2 ALGERIA WATANIYA TELECOM ALGERIE S.P.A. -

Ex-Post Analysis of the Merger Between H3G Austria and Orange Austria

Ex-post analysis of the merger between H3G Austria and Orange Austria RTR-GmbH March 2016 Table of Contents Deutsche Zusammenfassung............................................................... 2 Executive Summary .............................................................................. 4 1 Introduction .................................................................................. 6 2 Market situation ............................................................................ 6 3 Data and basket calculations ...................................................... 8 4 Qualitative comparison of price developments ......................... 9 5 Methodology of the estimation ................................................. 10 5.1 The difference-in-differences method (DID) ..............................................................11 5.2 The synthetic control group approach .......................................................................13 5.3 Basic specification and robustness checks ...............................................................15 6 Results of the estimation ........................................................... 15 7 Conclusion ................................................................................. 17 Annex ................................................................................................... 18 A1. Definition of baskets and price calculation .................................................................18 A2. Data description ........................................................................................................19 -

Sunrise Annual Report 2018

Sunrise Annual Report 2018 Annual Report 2018 WorldReginfo - 0c523c91-859a-40af-9558-9a8fc7c42e98 Facts & Figures Customers by subscription type Landline 3.525 network 13.3% million Mobile network Subscription 66.8% type Internet 13% Customers With more than 3.5 million customers, Sunrise TV is the leading privat owned telecom provider 6.9% in Switzerland, both in the mobile and landline network sectors. Additionally, Sunrise is the third largest provider of landline network, Internet and TV services. Revenue by subscription type Landline services 1,671 Mobile services Revenue (incl. voice) 67.7% 17.3% Employees 27.8% of the total number of 1,671 Sunrise Landline Internet employees (1,611 FTEs) are women. Approxi- (incl. IPTV) mately 13% of Sunrise employees work 15% part-time. Sunrise trains 140 apprentices in five apprenticeship programs. Company NPS Evolution 500% 98 400% 300% Offices and retail stores With 92 retail locations, Sunrise has a presence 200% in all regions of Switzerland. The Company is headquartered in Zurich and has additional 100% business offices in Prilly, Geneva, Bern, Basel 0% and Lugano. 2014 2015 2016 2017 2018 NPS improvement versus index 2014 WorldReginfo - 0c523c91-859a-40af-9558-9a8fc7c42e98 Content 2 Message to 77 Compensation Report Shareholders 78 Introduction by the Chairman of the Nomination and Compensation Committee 80 Compensation Governance 6 Financial and 82 Compensation System Operational KPIs 88 Board of Directors Compensation 90 Executive Leadership Team 7 Financial KPIs Compensation 8 Operational -

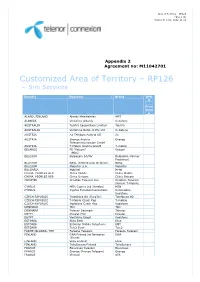

Customized Area of Territory – RP126 – Sim Services

Area of Territory – RP126 Page 1 (3) Version D rel01, 2012-11-21 Appendix 2 Agreement no: M11042701 Customized Area of Territory – RP126 – Sim Services Country Operator Brand GPR S Price Grou p ALAND, FINLAND Alands Mobiltelefon AMT ALBANIA Vodafone Albania Vodafone AUSTRALIA Telstra Corporation Limited Telstra AUSTRALIA Vodafone Network Pty Ltd Vodafone AUSTRIA A1 Telekom Austria AG A1 AUSTRIA Orange Austria Orange Telecommunication GmbH AUSTRIA T-Mobile Austria GmbH T-mobile BELARUS FE “Velcom” Velcom (MDC) BELGIUM Belgacom SA/NV Belgacom (former Proximus) BELGIUM BASE (KPN Orange Belgium) BASE BELGIUM Mobistar S.A. Mobistar BULGARIA Mobiltel M-tel CHINA, PEOPLES REP. China Mobile China Mobile CHINA, PEOPLES REP. China Unicom China Unicom CROATIA Croatian Telecom Inc. Croatian Telecom (former T-Mobile) CYPRUS MTN Cyprus Ltd (Areeba) MTN CYPRUS Cyprus Telecommunications Cytamobile- Vodafone CZECH REPUBLIC Telefónica O2 (EuroTel) Telefónica O2 CZECH REPUBLIC T-Mobile Czech Rep T-mobile CZECH REPUBLIC Vodafone Czech Rep Vodafone DENMARK TDC TDC DENMARK Telenor Denmark Telenor EGYPT Etisalat Misr Etisalat EGYPT Vodafone Egypt Vodafone ESTONIA Elisa Eesti Elisa ESTONIA Estonian Mobile Telephone EMT ESTONIA Tele2 Eesti Tele2 FAROE ISLANDS, THE Faroese Telecom Faroese Telecom FINLAND DNA Finland (fd Networks DNA (Finnet) FINLAND Elisa Finland Elisa FINLAND TeliaSonera Finland TeliaSonera FRANCE Bouygues Telecom Bouygues FRANCE Orange (France Telecom) Orange FRANCE Vivendi SFR Area of Territory – RP126 Page 2 (3) Version D rel01, 2012-11-21 GERMANY E-Plus Mobilfunk E-plus GERMANY Telefonica O2 Germany O2 GERMANY Telekom Deutschland GmbH Telekom (former T-mobile) Deutschland GERMANY Vodafone D2 Vodafone GREECE Vodafone Greece (Panafon) Vodafone GREECE Wind Hellas Wind Telecommunications HUNGARY Pannon GSM Távközlési Pannon HUNGARY Vodafone Hungary Ltd. -

Case No COMP/M.6497 – HUTCHISON 3G AUSTRIA / ORANGE AUSTRIA

EN This text is made available for information purposes only. A summary of this decision is published in all EU languages in the Official Journal of the European Union. Case No COMP/M.6497 – HUTCHISON 3G AUSTRIA / ORANGE AUSTRIA Only the EN text is authentic. REGULATION (EC) No 139/2004 MERGER PROCEDURE Article 8 (2) Date: 12/12/2012 EUROPEAN COMMISSION Strasbourg, 12.12.2012 C(2012) 9198final PUBLIC VERSION COMMISSION DECISION of 12.12.2012 addressed to: Hutchison 3G Austria Holdings GmbH declaring a concentration to be compatible with the internal market and the EEA agreement (Case No M.6497 – HUTCHISON 3G AUSTRIA / ORANGE AUSTRIA) (Text with EEA relevance) (Only the English text is authentic.) TABLE OF CONTENTS 1. THE PARTIES............................................................................................................. 7 2. THE CONCENTRATION........................................................................................... 8 2.1. The acquisition of Yesss! by TA.................................................................................. 9 2.2. Acquisition of Orange assets by TA from H3G........................................................... 9 3. UNION DIMENSION................................................................................................. 9 4. PROCEDURE............................................................................................................ 10 4.1. General procedure..................................................................................................... -

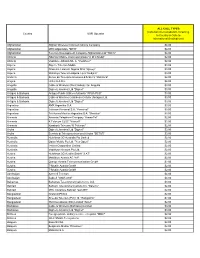

New Simplification Rates

ALL CALL TYPES (Calls back to Canada/US, Incoming, Country GSM Operator In Country & Calls to International Destinations) Afghanistan Afghan Wireless Communications Company $4.00 Afghanistan MTN Afganistan, "MTN" $4.00 Afghanistan Telecom Development Company Afghanistan Ltd "TDCA" $4.00 Albania Albanian Mobile Communications "A M C Mobil" $2.00 Albania Vodafone Albania Sh. A. "Vodafone" $2.00 Algeria Algerie Telecom Mobile $3.00 Algeria Orascom Telecom Algeria SPA "Djezzy" $3.00 Algeria Wataniya Telecom Algerie s.p.a."Nedjma" $3.00 Andorra Servei de Telecomunicacions d'Andorra "Mobiland" $2.00 Angola Unitel S.A.R.L. $4.00 Anguilla Cable & Wireless (West Indies) Ltd. Anguilla $3.00 Anguilla Digicel (Jamaica) Ltd "Digicel" $3.00 Antigua & Barbuda Antigua Public Utilities Authority "APUA PCS" $3.00 Antigua & Barbuda Cable & Wireless Caribbean Cellular (Antigua) Ltd. $3.00 Antigua & Barbuda Digicel (Jamaica) Ltd "Digicel" $3.00 Argentina AMX Argentina S.A. $3.00 Argentina Telecom Personal S.A. "Personal" $3.00 Argentina Telefonica Moviles Argentina S.A. "Movistar" $3.00 Armenia Armenia Telephone Company "ArmenTel" $2.00 Armenia K Telecom CJSC "Vivacell" $2.00 Armenia Karaback Telecom "K Telecom" $2.00 Aruba Digicel (Jamaica) Ltd "Digicel" $3.00 Aruba Servicio di Telecomunicacion di Aruba "SETAR" $3.00 Australia Hutchison 3G Australia Pty Limited $2.00 Australia Optus Mobile Pty Ltd. "Yes Optus" $2.00 Australia Telstra Corporation Limited $2.00 Australia Vodafone Network Pty Ltd. $2.00 Austria Hutchison 3G Austria GmbH "3 AT" $2.00 Austria Mobilkom Austria AG "A1" $2.00 Austria Orange Austria Telecommunication GmbH $2.00 Austria T-Mobile Austria GmbH $2.00 Austria T-Mobile Austria GmbH $2.00 Azerbaijan Azercell Telecom $4.00 Azerbaijan Bakcell "GSM 2000" $4.00 Bahamas Bahamas Telecommunications Co. -

CASE M.8792 - T-Mobile NL/Tele2 NL

EUROPEAN COMMISSION DG Competition CASE M.8792 - T-Mobile NL/Tele2 NL (Only the English text is authentic) MERGER PROCEDURE REGULATION (EC) 139/2004 Article 8 (1) Regulation (EC) 139/2004 Date: 27/11/2018 This is a provisional non-confidential version. The definitive non- confidential version will be published as soon as it is available. This text is made available for information purposes only. A summary of this decision will be published in all EU languages in the Official Journal of the European Union. Parts of this text have been edited to ensure that confidential information is not disclosed; those parts are enclosed in square brackets. EUROPEAN COMMISSION Brussels, 27.11.2018 C(2018) 7768 final PUBLIC VERSION COMMISSION DECISION of 27.11.2018 declaring a concentration to be compatible with the internal market and the functioning of the EEA Agreement (Case M.8792 - T-Mobile NL/Tele2 NL) (Only the English version is authentic) TABLE OF CONTENTS 1. Introduction ................................................................................................................ 11 2. The Parties and the Transaction ................................................................................. 12 3. Union dimension ........................................................................................................ 12 4. The procedure ............................................................................................................. 13 5. The investigation ....................................................................................................... -

Partnerzy Roamingowi

Partnerzy roamingowi Kraj Operator Aeroplanes AeroMobile AS (d. Telenor Mobile Aviation AS) Aeroplanes OnAir Switzerland Sarl Afghanistan Telecom Development Company Afghanistan Ltd. Afghanistan Afghan Wireless Communication Company Afghanistan Etisalat Afghanistan Albania Albanian Mobile Communications Albania Vodafone Albania Algeria Orascom Telecom Algerie Spa Algeria Wataniya Telecom Algerie Andorra Servei De Tele. DAndorra Angola Servei De Tele. DAndorra Anguilla under IRA with Mossel Limited T/A Digicel extended to it's affiliated network Digicel Anguilla Antigua & Barbuda under IRA with Mossel Limited T/A Digicel transferred from Cingular Wireless Argentina Nextel Communications, Inc. Argentina Telecom Personal Ltd. Argentina AMOV Argentina S.A. (d. AMX ARGENTINA S.A. , CTI Compania de Telefonos del Interior S.A.) Armenia ArmenTel Armenia K Telecom CJSC Aruba under IRA with Mossel Limited T/A Digicel extended to it's affiliated network New Millenium Telecom Services (NMTS) Australia Singtel Optus Limited Australia Telstra Corporation Ltd. Australia Vodafone Network Pty Ltd Austria Hutchison Drei Austria GmbH (d.Orange Austria Telecommunication GmbH (d. ONE GMBH / Connect Austria) Austria A1 Telekom Austria AG (d.Orange Austria Telecommunication GmbH (d. ONE GMBH / Connect Austria) Austria Hutchison Drei Austria GmbH (d.Hutchison 3G Austria GmbH Austria A1 Telekom Austria AG (d. Mobilkom Austria AG & Co KG) Austria Mobilkom Austria AG & Co KG Austria T-Mobile Austria GmbH (d. max.mobil Telekommunikation Service GmbH) Austria T-Mobile Austria GmbH (d. Tele.ring Telekom Service GmbH) Azerbaijan Azercell Telecom BM Azerbaijan Bakcell Ltd (d. J.V. Bakcell) Bahamas The Bahamas Telecommunications Company Ltd. Bahrain Bahrain Telecommunications Company Bahrain MTC VODAFONE (BAHRAIN) Bangladesh GrameenPhone Ltd Barbados under IRA with Mossel Limited T/A Digicel extended to it's affiliated network Digicel (Barbados) Limited Belarus FE VELCOM (d. -

Austria Profile | Point Topic Subscribers

Point Topic Austria Overview Austria 28 Nov 2016 Broadband Competitive Landscape Incumbent A1 Telekom Austria remains the dominant player in the fixed broadband market, with a 61 per cent share of subscriptions in Q2 2016. Its main competitor is Liberty Global's subsidiary UPC, with a 20 per cent share. Tele2 follows as a distant third with 4 per cent, while the remaining share of 15 per cent is shared by smaller players. In the xDSL market, the incumbent's retail arm has steadily strengthened its market leadership since 2008, increasing its share of DSL/VDSL subscriptions to 90 per cent by the end of Q2 2016. This domination can be attributed to the price reductions introduced by A1 in late 2007, which were, in turn, a response to competition from aggressively priced mobile broadband offers. Despite the introduction of lower wholesale charges for bitstream and LLU access, on the whole it became significantly more difficult for alternative operators to fight back against the incumbent, UPC and very competitive mobile broadband providers such as Drei Austria. In the cable market, the largest cable provider UPC continues the consolidation of smaller operators. UPC's network is fully DOCSIS 3-enabled, offering up to 250 Mbps broadband in the capital city of Vienna, the regional capitals of Graz, Klagenfurt, Innsbruck, and two smaller cities in the Vorarlberg region. In some areas, regional electricity providers are also actively participating in the broadband market as beneficiaries of the subsidy schemes set out in Austria's national broadband plan. As FTTP deployment throughout the country has been slow compared with the rest of Europe, with just under five per cent of population covered at the end of 2015, A1 Telekom announced that it will allocate EUR 400 million to the expansion of the national fibre network between 2015 and 2018.