WWI Service in Gallipoli

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Gallipoli Campaign Can in Large Measure Be Placed on His Shoulders

First published in Great Britain in 2015 P E N & S W O R D F A M I L Y H I S T O R Y an imprint of Pen & Sword Books Ltd 47 Church Street Barnsley South Yorkshire S70 2AS Copyright © Simon Fowler, 2015 ISBN: 978 1 47382 368 6 EPUB ISBN: 978 1 47385 188 7 PRC ISBN: 978 1 47385 195 5 The right of Simon Fowler to be identified as Author of the Work has been asserted by him in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988. A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library. All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical including photocopying, recording or by any information storage and retrieval system, without permission from the Publisher in writing. Typeset in Palatino and Optima by CHIC GRAPHICS Printed and bound in England by CPI Group (UK), Croydon, CR0 4YY Pen & Sword Books Ltd incorporates the imprints of Pen & Sword Archaeology, Atlas, Aviation, Battleground, Discovery, Family History, History, Maritime, Military, Naval, Politics, Railways, Select, Social History, Transport, True Crime, Claymore Press, Frontline Books, Leo Cooper, Praetorian Press, Remember When, Seaforth Publishing and Wharncliffe. For a complete list of Pen & Sword titles please contact PEN & SWORD BOOKS LTD 47 Church Street, Barnsley, South Yorkshire, S70 2AS, England E-mail: [email protected] Website: www.pen-and-sword.co.uk CONTENTS Preface Dardanelles or Gallipoli? Chapter 1 Gallipoli – an Overview ANZAC LANDING Chapter 2 Soldiers’ Lives SCIMITAR HILL Chapter 3 Getting Started DEATH AND THE FLIES Chapter 4 Researching British Soldiers and Sailors LANDING ON GALLIPOLI Chapter 5 Researching Units WAR DIARY, 2ND BATTALION, SOUTH WALES BORDERERS, 24–5 APRIL 1915 Chapter 6 The Royal Navy Chapter 7 Researching Dominion and Indian Troops Chapter 8 Visiting Gallipoli Bibliography PREFACE There is no other way to put it. -

Appendix F Ottoman Casualties

ORDERED TO DIE Recent Titles in Contributions in Military Studies Jerome Bonaparte: The War Years, 1800-1815 Glenn J. Lamar Toward a Revolution in Military Affairs9: Defense and Security at the Dawn of the Twenty-First Century Thierry Gongora and Harald von RiekhojJ, editors Rolling the Iron Dice: Historical Analogies and Decisions to Use Military Force in Regional Contingencies Scot Macdonald To Acknowledge a War: The Korean War in American Memory Paid M. Edwards Implosion: Downsizing the U.S. Military, 1987-2015 Bart Brasher From Ice-Breaker to Missile Boat: The Evolution of Israel's Naval Strategy Mo she Tzalel Creating an American Lake: United States Imperialism and Strategic Security in the Pacific Basin, 1945-1947 Hal M. Friedman Native vs. Settler: Ethnic Conflict in Israel/Palestine, Northern Ireland, and South Africa Thomas G. Mitchell Battling for Bombers: The U.S. Air Force Fights for Its Modern Strategic Aircraft Programs Frank P. Donnini The Formative Influences, Theones, and Campaigns of the Archduke Carl of Austria Lee Eystnrlid Great Captains of Antiquity Richard A. Gabriel Doctrine Under Trial: American Artillery Employment in World War I Mark E. Grotelueschen ORDERED TO DIE A History of the Ottoman Army in the First World War Edward J. Erickson Foreword by General Huseyin Kivrikoglu Contributions in Military Studies, Number 201 GREENWOOD PRESS Westport, Connecticut • London Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Erickson, Edward J., 1950— Ordered to die : a history of the Ottoman army in the first World War / Edward J. Erickson, foreword by General Htiseyin Kivrikoglu p. cm.—(Contributions in military studies, ISSN 0883-6884 ; no. -

Samai King Gifted and Talented Online Anzac Day: Why the Other Eight Months Deserve the Same Recognition As the Landing

THE Simpson PRIZE A COMPETITION FOR YEAR 9 AND 10 STUDENTS 2016 Winner Western Australia Samai King Gifted and Talented Online Anzac Day: Why The Other Eight Months Deserve The Same Recognition As The Landing Samai King Gifted and Talented Online rom its early beginnings in 1916, Anzac Day and the associated Anzac legend have come to be an essential part of Australian culture. Our history of the Gallipoli campaign lacks a consensus view as there are many Fdifferent interpretations and accounts competing for our attention. By far the most well-known event of the Gallipoli campaign is the landing of the ANZAC forces on the 25th of April, 1915. Our celebration of, and obsession with, just one single day of the campaign is a disservice to the memory of the men and women who fought under the Anzac banner because it dismisses the complexity and drudgery of the Gallipoli campaign: the torturous trenches and the ever present fear of snipers. Our ‘Anzac’ soldier is a popularly acclaimed model of virtue, but is his legacy best represented by a single battle? Many events throughout the campaign are arguably more admirable than the well-lauded landing, for example the Battle for Lone Pine. Almost four times as many men died in the period of the Battle of Lone Pine than during the Landing. Statistics also document the surprisingly successful evacuation - they lost not even a single soldier to combat. We have become so enamored by the ‘Landing’ that it is now more celebrated and popular than Remembrance Day which commemorates the whole of the First World War in which Anzacs continued to serve. -

April 1915 / Avril 1915

World War I Day by Day 1915 – 1918 April 1915 / Avril 1915 La premiere guerre mondiale De jour en jour 1915 – 1918 Friends of the Canadian War Museum – Les amis du Musée canadien de la guerre https://www.friends-amis.org/ © 2019 FCWM - AMCG 9 April 1915 The Bunsen Committee: The powerbroker for the Middle East The British Government was puzzled by what would follow a victory against the Ottoman Empire. All major powers of Europe had a stake in the Middle East and the division of the spoils would inevitably bring some difficulties. For a full century, the carving of the Sick Man of Europe had been postponed by conferences to avoid European wars. Prime Minister Asquith therefore created a committee, on 9 April 1915, under a senior Foreign Office diplomat, Maurice de Bunsen, to propose a policy in regard to the division of the Middle East among Allies. The Bunsen Committee had representatives from the Colonial Office, the Admiralty, the India Office and other relevant departments. The War Office was officially represented by General Sir Charles Calwell, but Kitchener Colonel Sir Tatton Benvenuto Mark Sykes, 6th Baronet (16 March 1879 – 16 February 1919) insisted that he should have his own personal representative on the Committee. That representative was Sir Mark Sykes, a Member of Parliament who was well known as a Kitchener hand with some experience in Constantinople, and who would turn out to influence the committee to the point of singlehanded direction. This committee will produce a first report in June 1915 but will continue as a think-tank for the British government on Middle Eastern developments. -

“Come on Lads”

“COME ON LADS” ON “COME “COME ON LADS” Old Wesley Collegians and the Gallipoli Campaign Philip J Powell Philip J Powell FOREWORD Congratulations, Philip Powell, for producing this short history. It brings to life the experiences of many Old Boys who died at Gallipoli and some who survived, only to be fatally wounded in the trenches or no-man’s land of the western front. Wesley annually honoured these names, even after the Second World War was over. The silence in Adamson Hall as name after name was read aloud, almost like a slow drum beat, is still in the mind, some seventy or more years later. The messages written by these young men, or about them, are evocative. Even the more humdrum and everyday letters capture, above the noise and tension, the courage. It is as if the soldiers, though dead, are alive. Geoffrey Blainey AC (OW1947) Front cover image: Anzac Cove - 1915 Australian War Memorial P10505.001 First published March 2015. This electronic edition updated February 2017. Copyright by Philip J Powell and Wesley College © ISBN: 978-0-646-93777-9 CONTENTS Introduction .................................................................................. 2 Map of Gallipoli battlefields ........................................................ 4 The Real Anzacs .......................................................................... 5 Chapter 1. The Landing ............................................................... 6 Chapter 2. Helles and the Second Battle of Krithia ..................... 14 Chapter 3. Stalemate #1 .............................................................. -

ÖN TARAF.Pdf

OTELLER VE PANSİYONLAR / HOTELS & HOSTELS TARİHİ ALAN Kartal T. Ece Limanı KILAVUZ HARİTASI A-14 Domuzpazarı (Mvk.) Aktaş T. Yurtyeri Kapanca T. (Mvk.) r: 200 km r: 500 km İSTANBUL SAMSUN Masırlı KARS (Mvk.) TRABZON ANKARA ERZURUM North Redoubt ÇANAKKALE Dolaplar ERZİNCAN Kireç Tepe (Mvk.) SİVAS Kuş Br. ELAZIĞ MUŞ Kireç T. Top T. TA-65 SİİRT İZMİR DENİZLİ KAYSERİ VAN Limestone Hill MALATYA BATMAN TA-64 BODRUM DİYARBAKIR Taşkapı ŞANLIURFA ADANA GAZİANTEP TA-63 Meşelieğrek T. DALAMAN ANTALYA Toplar (Mvk.) TA-62 Mersinli T. Jephson's Post EDİRNE TA-61 Kavak T. KARAKOL DAĞI KARADENİZ Karakol Dagh Taşaltı BULGARİSTAN BLACK SEA Uçurum (Mvk.) A-13 BULGARIA Horoz ayıtlığı (Mvk.) . Kidney Hill İSTANBUL Söğütler yanı Tekke T. YUNANİSTAN Azmakköprü (Mvk.) GREECE TEKİRDAĞ Sarplar Sr Çıralçeşme (Mvk.) (Mvk.) Gala Gölü KOCAELİ Limandağ ovası YA-26 Büyükkemikli Br. (Mvk.) Geyve Gölü MARMARA DENİZİ MARMARA SEA SUVLA POINT Karacaorman Harmanlar (Mvk.) Hanaybayırı A-12 TA-60 Çakal T. Dolmacıdede Softa T. Barış Parkı Askerkuyu T. Peace Park BURSA Hill 10 Gökçeada Karaincirler ÇANAKKALE (Mvk.) Yolağzı Kuş Cenneti YA-25 Çanakkale Savaşları Otoyollar 'A' Beach Taşmerdiven T. Büngüldek T. Bozcaada Gelibolu Tarihi Alan Başkanlığı Highways Troia Göknarı Tabiat Koruma Alanı Ana Asfalt Yollar Küçük Anafarta Natural Conservation Site Main Asphalt Roads EGE DENİZİ Kangoroo Beach Kazdağı Ara Asphalt Yollar Kavakkarşısı T. AEGEAN SEA BALIKESİR Tabiat Parkları Edremt Natural Parks Secondary Asphalt Roads Milli Parklar Deniz Bağlantıları Karabacakharman Yakababa T. Ayvalık Passenger Ferry Üçpınarlar Liman (Mvk.) Kaplan T. Adaları Seaport (Mvk.) Yat Rotaları Recommended The Cut . Havaalanı Suvla Koyu Airport Yacht Route TA-67 A-15 Suvla Bay B01B-15 Kovarlık Sr Gemikaya Mocalar TA-68 TA-66 (Mvk.) Yusufçuk Tepe Tataroğlunun Bucazeytin TUZ GÖLÜ B-14 (Mvk.) Scimitar Hill Koza T. -

The Forgotten Fronts the First World War Battlefield Guide: World War Battlefield First the the Forgotten Fronts Forgotten The

Ed 1 Nov 2016 1 Nov Ed The First World War Battlefield Guide: Volume 2 The Forgotten Fronts The First Battlefield War World Guide: The Forgotten Fronts Creative Media Design ADR005472 Edition 1 November 2016 THE FORGOTTEN FRONTS | i The First World War Battlefield Guide: Volume 2 The British Army Campaign Guide to the Forgotten Fronts of the First World War 1st Edition November 2016 Acknowledgement The publisher wishes to acknowledge the assistance of the following organisations in providing text, images, multimedia links and sketch maps for this volume: Defence Geographic Centre, Imperial War Museum, Army Historical Branch, Air Historical Branch, Army Records Society,National Portrait Gallery, Tank Museum, National Army Museum, Royal Green Jackets Museum,Shepard Trust, Royal Australian Navy, Australian Defence, Royal Artillery Historical Trust, National Archive, Canadian War Museum, National Archives of Canada, The Times, RAF Museum, Wikimedia Commons, USAF, US Library of Congress. The Cover Images Front Cover: (1) Wounded soldier of the 10th Battalion, Black Watch being carried out of a communication trench on the ‘Birdcage’ Line near Salonika, February 1916 © IWM; (2) The advance through Palestine and the Battle of Megiddo: A sergeant directs orders whilst standing on one of the wooden saddles of the Camel Transport Corps © IWM (3) Soldiers of the Royal Army Service Corps outside a Field Ambulance Station. © IWM Inside Front Cover: Helles Memorial, Gallipoli © Barbara Taylor Back Cover: ‘Blood Swept Lands and Seas of Red’ at the Tower of London © Julia Gavin ii | THE FORGOTTEN FRONTS THE FORGOTTEN FRONTS | iii ISBN: 978-1-874346-46-3 First published in November 2016 by Creative Media Designs, Army Headquarters, Andover. -

The Semaphore Circular No 647 the Beating Heart of the RNA March 2015

The Semaphore Circular No 647 The Beating Heart of the RNA March 2015 Chrissie Hughes (Shipmates Administrator), Michelle Bainbridge (Financial Controller) and Life Vice President Rita Lock MBE offer sage instructions to AB Andy Linton and AB Jo Norcross at HQ after they were ‘Volunteered’ for supplementary duties with the RNA! Andy and Jo commented later it is a character building experience!! RNA members are reminded that hard-copies of the Circular are distributed to each branch via their Secretary, but “silver-surfers” can download their own copy from the RNA website at www.royal-naval-association.co.uk .(See below) Daily Orders 1. Welfare Seminar Update 2. IMC Sailing Camp 3. Gallipoli Event Whitehall 4. 75th Anniversary of Dunkirk Invitation 5. Guess Where? 6. Can anyone beat this Car Registration 7. Request for assistance 8. Finance Corner 9. Donations received 10. Free to a good home 11. Di from Llandrod Wells 12. Caption Competition 13. Can you assist 14. Spotters Corner 15. The Atheist and the Bear 16. Virtual Branch 17. RN VC Series – Captain Edward Unwin 18. Fifty Shades of Pussers Grey 19. Type 21 Memorial 20. Old Ships 21. HMS M33 Appeal 22. Down Memory Lane Longcast “D’ye hear there” (Branch news) Ship’s Office 1. Swinging the Lamp For the Branch Secretary and notice-board Glossary of terms NCM National Council Member NC National Council AMC Association Management Committee FAC Finance Administration Committee NCh National Chairman NVCh National Vice Chairman NP National President DNP Deputy National President GS General -

Catalogue: May #2

CATALOGUE: MAY #2 MOSTLY OTTOMAN EMPIRE, THE BALKANS, ARMENIA AND THE MIDDLE EAST - Books, Maps & Atlases 19th & 20th Centuries www.pahor.de 1. COSTUMES OF THE OTTOMAN EMPIRE A small, well made drawing represents six costumes of the Ottoman Empire and the Middle East. The numeration in the lower part indicates, that the drawing was perhaps made to accompany a Anon. [Probably European artist]. text. S.l., s.d. [Probably mid 19th century] Pencil and watercolour on paper (9,5 x 16,5 cm / 3.7 x 6.5 inches), with edges mounted on 220 EUR later thick paper (28 x 37,5 cm / 11 x 14,8 inches) with a hand-drawn margins (very good, minor foxing and staining). 2. GREECE Anon. [Probably a British traveller]. A well made drawing represents a Greek house, indicated with a title as a house between the port city Piraeus and nearby Athens, with men in local costumes and a man and two young girls in House Between Piraeus and Athens. central or west European clothing. S.l., s.d. [Probably mid 19th century]. The drawing was perhaps made by one of the British travellers, who more frequently visited Black ink on thick paper, image: 17 x 28 cm (6.7 x 11 inches), sheet: 27 x 38,5 cm (10.6 x 15.2 Greece in the period after Britain helped the country with its independence. inches), (minor staining in margins, otherwise in a good condition). 160 EUR 3. OTTOMAN GEOLOGICAL MAP OF TURKEY: Historical Context: The Rise of Turkey out of the Ottoman Ashes Damat KENAN & Ahmet Malik SAYAR (1892 - 1965). -

7-9 Booklist by Title - Full

7-9 Booklist by Title - Full When using this booklist, please be aware of the need for guidance to ensure students select texts considered appropriate for their age, interest and maturity levels. This title also appears on the 9plus booklist. This title is usually read by students in years 9, 10 and above. PRC Title/Author Publisher Year ISBN Annotations 5638 1000-year-old boy, The HarperCollins 2018 9780008256944 Alfie Monk is like any other pre-teen, except he's 1000 years old and Welford, Ross Children's Books can remember when Vikings invaded his village and he and his family had to run for their lives. When he loses everything he loves in a tragic fire and the modern world finally catches up with him, Alfie embarks on a mission to change everything by finally trusting Aidan and Roxy enough to share his story, and enlisting their help to find a way to, eventually, make sure he will eventually die. 22034 13 days of midnight Orchard Books 2015 9781408337462 Luke Manchett is 16 years old with a place on the rugby team and the Hunt, Leo prettiest girl in Year 11 in his sights. Then his estranged father suddenly dies and he finds out that he is to inherit six million dollars! But if he wants the cash, he must accept the Host. A collection of malignant ghosts who his Necromancer father had trapped and enslaved! Now the Host is angry, the Host is strong, and the Host is out for revenge! Has Luke got what it takes to fight these horrifying spirits and save himself and his world? 570824 13th reality, The: Blade of shattered hope Scholastic Australia 2018 9781742998381 Tick and his friends are still trying to work out how to defeat Mistress Dashner, James Jane, but when there are 13 realities from which to draw trouble, the battle is 13 times as hard. -

Letter from a Pilgrimage 8 2

LETTERS FROM A PILGRIMAGE Ken Inglis’s despatches from the Anzac tour to Gallipoli, April–May 1965 LETTERS FROM A PILGRIMAGE Ken Inglis’s despatches from the Anzac tour of Greece and Turkey, April–May 1965 First published in e Canberra Times, 15 April–1 May 1965 Republished by Inside Story, April 2015 Ken Inglis is Emeritus Professor (History) at the Australian National University and an Honorary Professor in the National Centre for Australian Studies at Monash University. He has published widely on the Anzac tradition and intellectual history. He travelled with the Anzac Pilgrims in 1965 as correspondent for e Canberra Times. Cover: Anzacs going ashore at dawn on 25 April 1965. Photo: Ken Inglis Preface adapted from Observing Australia: 1959 to 1999, by K.S. Inglis, edited and introduced by Craig Wilcox, Melbourne University Press, 1999 DOI 10.4225/50/5535D349F3180 Inside Story Swinburne Institute for Social Research PO Box 218, Hawthorn, Victoria 3122 insidestory.org.au Contents Preface 5 1. Letter from a pilgrimage 8 2. Anzac Diggers see Tobruk and cheer 15 3. Why they came 21 4. Nasser earns the Anzacs’ admiration 24 5. Stepping ashore tomorrow on Australia’s “holy land” 31 6. Anzacs play to Turkish rules on their return 38 7. 10,000 miles and back to commune with Anzac dead 45 4 Preface n 1965 the Returned Services League, or RSL, and its New Zealand equivalent sponsored a three-week cruise around the Mediterranean arranged by Swan Hellenic Tours, vis- iting sites of significance in Anzac memory and culminat- ing in a landing at Anzac Cove on the fiftieth anniversary Iof the first one. -

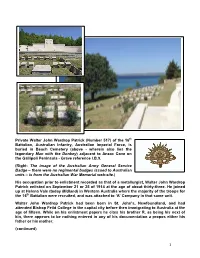

Patrick, Walter John Wardrop

Private Walter John Wardrop Patrick (Number 517) of the 16th Battalion, Australian Infantry, Australian Imperial Force, is buried in Beach Cemetery (above - wherein also lies the legendary Man with the Donkey) adjacent to Anzac Cove on the Gallipoli Peninsula - Grave reference I.B.9. (Right: The image of the Australian Army General Service Badge – there were no regimental badges issued to Australian units – is from the Australian War Memorial web-site.) His occupation prior to enlistment recorded as that of a metallurgist, Walter John Wardrop Patrick enlisted on September 21 or 25 of 1914 at the age of about thirty-three. He joined up at Helena Vale (today Midland) in Western Australia where the majority of the troops for the 16th Battalion were recruited, and was attached to ‘A’ Company in that same unit. Walter John Wardrop Patrick had been born in St. John’s, Newfoundland, and had attended Bishop Feild College in the capital city before then immigrating to Australia at the age of fifteen. While on his enlistment papers he cites his brother R. as being his next of kin, there appears to be nothing entered in any of his documentation a propos either his father or his mother. (continued) 1 It was on December 22 of that same year that the personnel of the 16th Battalion – thirty-two officers and nine-hundred seventy-nine other ranks, among that number Private Patrick – embarked in the port of Melbourne onto His Majesty’s Australian Transport Ceramic for passage to the Middle East. It was to be a six-week journey.