12 06 Irony in Daniel Catán's Salsipuedes

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

MLA Newsletter (144)

MMLLAA NEWSLETTER A 75th Anniversary Meeting in Memphis Inside: President’s Report . 2 Calendar . .17 Chapter Reports . 22 Annual Meeting . 3 Transitions . 18 Announcements . 24 Committee Reports . 16 Roundtable Reports . 19 Beyond MLA . 26 No. 144 March–April 2006 ISSN 0580-289-X Chapter Reports President’s Report MUSIC LIBRARY ASSOCIATION BOARD OF DIRECTORS Bonna Boettcher, MLA President was spon- Officers sored by the BONNA J. BOETTCHER, President Women and Bowling Green State University th hat a wonderful 75 an- Music Roundtable, the American PHILIP VANDERMEER, niversary meeting! Those Music Roundtable, and the Joint Vice President/President Elect University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill who were able to attend Committee on the MLA Archives. W NANCY NUZZO, our recent meeting in Memphis en- Both plenaries were videotaped for Treasurer/Executive Secretary joyed warm, southern hospitality and the archives. The final plenary ses- State University of New York, Buffalo a chance to reflect on the history of sion, moderated by Brian Doherty KAREN LITTLE, Recording Secretary our association while looking toward and focusing on collection develop- University of Louisville the future. We owe a great deal to ment, included Jim Cassaro, Michael Members-at-Large 2005–2007 the Local Arrangements Committee, Fling, Dan Zager, and Daniel Boom- LINDA W. BLAIR chaired by Anna Neal, to Laurel hower. This session was sponsored Eastman School of Music Whisler, for coordinating fundraising by the Resource Sharing and Collec- PAUL CAUTHEN efforts, to Roberta Chodacki Ford, for tion Development Committee. University of Cincinnati chairing the Ad hoc Committee on In addition to the plenary ses- AMANDA MAPLE Penn State University MLA’s 75th Anniversary, and to the sion, there were many other excel- entire Southeast Chapter for lent sessions. -

The Deep Sounds of Mexico - LA Times

The deep sounds of Mexico - LA Times SUBSCRIBE ENTERTAINMENT LOCAL SPORTS POLITICS OPINION PLACE AN AD 72° The deep sounds of Mexico By Chris Pasles Times Staff Writer APRIL 15, 2007 HAT happens when an expert shoots down your bright idea? That's what Pacific Symphony music director Carl St.Clair and the W orchestra's artistic advisor, Joseph Horowitz, faced when Gregorio Luke, director of the Museum of Latin American Art in Long Beach, saw their plans for an American Composers Festival called "Los Sonidos de Mexico" (The Sounds of Mexico). "He said, 'All you're doing is perpetuating a stereotype of Mexico as a surrogate of Hispanic culture, whereas it is the most polyglot culture of any nation,'" Horowitz By continuing to use our site, you agree to our Terms of Service and Privacy Policy. You can learn more about how we use cookies by reviewingrecalled. our Privacy" 'If you Policy want. Close to do something really important and original, tell the whole https://www.latimes.com/archives/la-xpm-2007-apr-15-ca-pacific15-story.html[13/06/2019 06:07:42 p. m.] The deep sounds of Mexico - LA Times story of Mexican music, beginning with pre-Hispanic and going on through Baroque, Romantic 19th century music, Modernism and what happened after Modernism.' "We immediately understood he was right," said Horowitz. "We redrew the framework of our festival completely." Their redesign, the seventh such event the Pacific Symphony has programmed, is to open this afternoon at the Irvine Barclay Theatre and end April 29 at the Renee and Henry Segerstrom Concert Hall in Costa Mesa. -

Media Release

Media Release FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE: December 14, 2017 Contact: Edward Wilensky (619) 232-7636 [email protected] San Diego Opera’s Main Stage Season Closes on March 17, 2018 with Daniel Catán’s Florencia en el Amazonas All Spanish speaking cast led by soprano Elaine Alvarez as Florencia Most famous work by Mexican composer Daniel Catán inspired by the Magical Realism of author Gabriel García Márquez San Diego, CA – San Diego Opera’s 2017-2018 mainstage season comes to close with Daniel Catán’s ode to magic realism, Florencia en el Amazonas, which opens on Saturday, March 17, 2018 at 7 PM at the San Diego Civic Theatre. Additional performances are March 20, 23, and 25 (matinee), 2018. Daniel Catán’s history with the Company goes back quite some time as San Diego Opera gave Catán’s opera, Rappacini’s Daughter, its American premiere, making him the first Mexican composer to have his work presented professionally in the United States. The success of Rapaccini’s Daughter led to international acclaim that resulted in the commissioning for Florencia en el Amazonas by Houston Grand Opera. Loosely inspired by Gabriel García Márquez’s novel, Love in the Time of Cholera, the opera follows the fictional opera singer Florencia Grimaldi as she returns to perform in her home town with the hopes of attracting the attention of her long lost love who has vanished in the Amazon forest collecting butterflies. As she journeys down the Amazon on a riverboat, Florencia becomes entwined in the lives of the other passengers whose conversations and passions lead her to self-realization and a metamorphosis. -

Daniel Catán

Daniel Catán: An Inventory of His Papers at the Harry Ransom Center Descriptive Summary Creator: Catán, Daniel, 1948-2011 Title: Daniel Catán Papers, Dates: 1949-2014 Extent: 14 document boxes, 24 oversize boxes (osb) (15.96 linear feet), 1 oversize folder (osf) Abstract: The Daniel Catán papers consist of audio files, awards, certificates, clippings, diplomas, photographs, posters, printouts of web pages, programs, scores, scrapbooks, serial publications, sheet music, and video files documenting the career of Daniel Catán, Mexican-born composer of operas and other musical works. Call Number: Manuscript Collection MS-05283 Language: English and Spanish Access: Open for research. Some materials restricted because of fragile condition; digital surrogates are available. Researchers must create an online Research Account and agree to the Materials Use Policy before using archival materials. Use Policies Ransom Center collections may contain material with sensitive or confidential information that is protected under federal or state right to privacy laws and regulations. Researchers are advised that the disclosure of certain information pertaining to identifiable living individuals represented in the collections without the consent of those individuals may have legal ramifications (e.g., a cause of action under common law for invasion of privacy may arise if facts concerning an individual's private life are published that would be deemed highly offensive to a reasonable person) for which the Ransom Center and The University of Texas at Austin assume no responsibility. Restrictions on Authorization for publication is given on behalf of the University of Use Texas as the owner of the collection and is not intended to include or imply permission of the copyright holder which must be obtained by the researcher. -

JUNE 2016 World Premiere of David Hertzberg's “Sunday Morning”

NEW YORK CITY OPERA RETURNS WITH THREE PREMIERES MARCH - JUNE 2016 World Premiere of David Hertzberg’s “Sunday Morning” at Inaugural New York City Opera Concerts at Appel Room in March 2016 East Coast Premiere of Hopper’s Wife at Harlem Stage in April 2016 New York City Professional Premiere of Florencia en el Amazonas Launches Spanish-language Opera Series: Ópera en Español Jazz at Lincoln Center’s Rose Theater in June 2016 February 22, 2016 – New York City Opera General Director Michael Capasso today announced the remainder of the 2016 season. New York City Opera will present three major premieres including the world premiere of “Sunday Morning” by David Hertzberg as part of the inaugural New York City Opera Concerts at Jazz at Lincoln Center’s Appel Room on March 16; the East Coast premiere of Stewart Wallace and Michael Korie’s Hopper’s Wife presented at Harlem Stage in April 2016 and the New York City professional premiere of Daniel Catán’s Florencia en el Amazonas at Jazz at Lincoln Center’s Rose Theater in June 2016. Florencia en el Amazonas launches Spanish-language Opera Series, Ópera en Español. Michael Capasso discussed the season, “In continuing with my vision for New York City Opera, these three offerings of contemporary music balance the traditional Tosca production with which we re-launched the company in January. Historically, New York City Opera presented a combination of core and contemporary repertoire; this programming represents our commitment to maintaining that approach. The initiation of our New York City Opera Concerts at the Appel Room will demonstrate further our company’s versatility and goal to present events that complement our staged productions. -

Houston Grand Opera's 2017–18 Season Features Long-Awaited Return of Strauss's Elektra

Season Update: Houston Grand Opera’s 2017–18 Season Features Long-Awaited Return of Strauss’s Elektra and Bellini’s Norma, World Premiere of Ricky Ian Gordon/Royce Vavrek’s The House without a Christmas Tree, First Major American Opera House Presentation of Bernstein’sWest Side Story Company’s six-year multidisciplinary Seeking the Human Spirit initiative begins with opening production of La traviata Updated July 2017. Please discard previous 2017–18 season information. Houston, July 28, 2017— Houston Grand Opera expands its commitment to broadening the audience for opera with a 2017–18 season that includes the first presentations of Leonard Bernstein’s classic musical West Side Story by a major American opera house and the world premiere of composer Ricky Ian Gordon and librettist Royce Vavrek’s holiday opera The House without a Christmas Tree. HGO will present its first performances in a quarter century of two iconic works: Richard Strauss’s revenge-filled Elektra with virtuoso soprano Christine Goerke in the tempestuous title role and 2016 Richard Tucker Award–winner and HGO Studio alumna Tamara Wilson in her role debut as Chrysothemis, under the baton of HGO Artistic and Music Director Patrick Summers; and Bellini’s grand-scale tragedy Norma showcasing the role debut of stellar dramatic soprano Liudmyla Monastyrska in the notoriously difficult title role, with 2015 Tucker winner and HGO Studio alumna Jamie Barton as Adalgisa. The company will revive its production of Handel’s Julius Caesar set in 1930s Hollywood, featuring the role debuts of star countertenor Anthony Roth Costanzo (HGO’s 2017–18 Lynn Wyatt Great Artist) and Houston favorite and HGO Studio alumna soprano Heidi Stober as Caesar and Cleopatra, respectively, also conducted by Maestro Summers; and Rossini’s ever-popular comedy, The Barber of Seville, with a cast that includes the eagerly anticipated return of HGO Studio alumnus Eric Owens, Musical America’s 2017 Vocalist of the Year, as Don Basilio. -

Nashville Opera to Present Daniel Catán's Lush Contemporary

Nashville Opera to present Daniel Catán’s lush contemporary masterpiece, Florencia en el Amazonas • Nashville Opera’s first Spanish-language production • Libretto is an homage to the Pulitzer-prize winning novel, Love in the Time of Cholera by Gabriel García Marquez. • City-wide events include a visual art show at The Arts Company and educational programming through Vanderbilt University’s Center for Latin American Studies (CLAS) • Collaboration with the Metro Nashville Arts Commission, The Arts Company, Vanderbilt University’s Center for Latin American Studies (CLAS), and Casa Azafrán. November 18, 2014 (NASHVILLE, TN) — Nashville Opera will present Daniel Catán’s romantic contemporary masterpiece, Florencia en el Amazonas on Friday, January 23 at 8 PM; Sunday, January 25 at 2 PM; and Tuesday, January 27 at 7 PM at the Tennessee Performing Arts Center’s James K. Polk Theater, located at 505 Deaderick Street in Downtown Nashville. Florencia en el Amazonas is directed by John Hoomes with Maestro Dean Williamson leading the Nashville Opera Orchestra. Tickets range from $26 to $102.50 and are available by calling Nashville Opera at (615) 832-5242, the Tennessee Performing Arts Center Box Office at (615) 782-4040, or online at www.nashvilleopera.org. Si desea comprar entradas para eventos en el TPAC y necesita ayuda en español, por favor llame al 1-800-664-8941. A limited number of “pay-what-you-can” seats may be purchased directly from Nashville Opera’s main offices at the Noah Liff Opera Center in Sylvan Heights for a minimum suggested donation of $5. Mr. Hoomes will present the popular Opera Insights discussion one-hour prior to curtain on the Orchestra Level. -

Lucia Di Lammermoor GAETANO DONIZETTI MARCH 3 – 11, 2012

O p e r a B o x Teacher’s Guide table of contents Welcome Letter . .1 Lesson Plan Unit Overview and Academic Standards . .2 Opera Box Content Checklist . .9 Reference/Tracking Guide . .10 Lesson Plans . .12 Synopsis and Musical Excerpts . .44 Flow Charts . .49 Gaetano Donizetti – a biography .............................56 Catalogue of Donizetti’s Operas . .58 Background Notes . .64 Salvadore Cammarano and the Romantic Libretto . .67 World Events in 1835 ....................................73 2011–2012 SEASON History of Opera ........................................76 History of Minnesota Opera, Repertoire . .87 così fan tutte WOLFGANG AMADEUS MOZART The Standard Repertory ...................................91 SEPTEMBER 25 –OCTOBER 2, 2011 Elements of Opera .......................................92 Glossary of Opera Terms ..................................96 silent night KEVIN PUTS Glossary of Musical Terms . .101 NOVEMBER 12 – 20, 2011 Bibliography, Discography, Videography . .105 werther Evaluation . .108 JULES MASSENET JANUARY 28 –FEBRUARY 5, 2012 Acknowledgements . .109 lucia di lammermoor GAETANO DONIZETTI MARCH 3 – 11, 2012 madame butterfly mnopera.org GIACOMO PUCCINI APRIL 14 – 22, 2012 FOR SEASON TICKETS, CALL 612.333.6669 620 North First Street, Minneapolis, MN 55401 Kevin Ramach, PRESIDENT AND GENERAL DIRECTOR Dale Johnson, ARTISTIC DIRECTOR Dear Educator, Thank you for using a Minnesota Opera Opera Box. This collection of material has been designed to help any educator to teach students about the beauty of opera. This collection of material includes audio and video recordings, scores, reference books and a Teacher’s Guide. The Teacher’s Guide includes Lesson Plans that have been designed around the materials found in the box and other easily obtained items. In addition, Lesson Plans have been aligned with State and National Standards. -

And Return of Cruzar La Cara De La Luna (May 17, 19, 20) at HGO Resilience Theater

Houston Grand Opera presents Bernstein’s West Side Story (April 20–May 6), Bellini’sNorma (April 27–May 11), and return of Cruzar la Cara de la Luna (May 17, 19, 20) at HGO Resilience Theater World’s first mariachi opera returns after New York triumph Houston, January 29, 2018— Houston Grand Opera (HGO) will present the first major American opera house production of Leonard Bernstein’s landmark musical West Side Story, April 20–May 6, and Bellini’s vocal powerhouse Norma, April 27–May 11, in the HGO Resilence Theater at the George R. Brown Convention Center. HGO will also bring back its popular groundbreaking production of the world’s first mariachi opera, Cruzar la Cara de la Luna/To Cross the Face of the Moon, for three special performances on May 17, 19, and 20, also in Resilience Theater. Composed by José “Pepe” Martínez with libretto by Leonard Foglia, the powerful story chronicling three generations of a family divided by countries and cultures has been performed to audience and critical acclaim all over the United States, in Paris, and in Mexico. It received rave reviews at its New York premiere at New York City Opera. Tickets for these productions at the HGO Resilience Theater in the George R. Brown Convention Center are available at HGO.org. Parking is available at the Avenida North Garage located at 1815 Rusk 1 Street, across from Resilience Theater. A sky bridge connects the parking garage to the GRB, and there is clear signage directing patrons to the theater. More information about parking can be found here. -

CHAD SHELTON, Tenor

CHAD SHELTON, tenor Opera News praises tenor Chad Shelton for one of his trademark roles, claiming that his “Don José was the dramatic heart of this production; this was a performance that grew in complexity as he struggled to recon- cile the forces of loyalty, lust and fate. Shelton owned the final scene, as his character descended into despair fueled by psychotic obsession. His bright tone amplified the intensity of the last gripping moments.” In the 2016-17 season, he makes returns to the Grand Théâtre de Genève for his first performances of Sir Edgar Aubry in Der Vampyr and Houston Grand Opera to reprise Chairman Mao in Adams’ Nixon in China and sings Don Jose in Carmen on tour in Japan as a guest artist of the Seiji Ozawa Music Academy Opera Project. He also sings his first perfor- mances of Mahler’s Das Lied von der Erde with the Phoenix Symphony and returns to the roster of the Metropolitan Opera for its production of Cyrano de Bergerac. Last season, he retured to Houston Grand Opera for Cavardossi in Tosca and to create the role of Charles II in the world premiere of Carlisle Floyd’s Prince of Players. He made his Metropolitan Opera debut as Rodrigo in a new production of Otello and also joined the company for Elektra in addition to returning to one of his most fre- quently performed roles, Alfredo in La traviata, with Pensacola Opera. He has joined the Opéra National de Lorraine numerous times, including for the title role of Idomeneo, Giasone in Cherubini’s Medea, Don Jose in Carmen, Jack in Gerald Barry’s The Importance of Being Earnest, Lysander in A Midsummer Night’s Dream, Guido Bardi in Eine floren- tinische Tragödie, Lechmere in Owen Wingrave, Tamino in Die Zauber- flöte, and the title role of Candide. -

Nixon in China Program & Bios

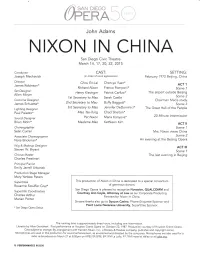

1/\ SANnirs* il\ t/-\ , ', :l ; J\" ! ffire&'-J \-*-/ JohnAdams NIXONIN CHINA SanDiego CivicTheatre March14, 17, 20,22,2015 Conductor CAST: SETTING: JosephMechavich (in order of vocal appearance) February1972 Beijing, China Director Chou En-Lai Chen-yeYuan* JamesRobinson* ACT 1 RichardNixon FrancoPomponi* Scene 7 (ai Dacianar Henry Krssinger PatrickCartizzi* The airporloutside Beijing Allen Moyer 1stSecretaryr to Mao SarahCastle Scene2 CostumeDesigner ChairmanMao's study 2nd Secretaryto Mao BuffyBaggott* James Schuette* Scene3 3rd Secretaryto Mao JenniferDeDominici* Lighting Designer The GreatHall of the People Paul Palazzo* Mao Tse-Tung ChadShelton* 20 Minute lntermission SoundDesigner Pat Nxon MariaKanyova* MadameMao Kathleen Brian Mohr* Kim ACT II t"l^^-^^^-^^L^- vt tvrcvyr aPt tcr Scene 7 Se5n Curran Mrs.Nixon views China AssociateChoreographer Scene2 Nora Brickman* An eveningat the BeijingOpera Wig & Makeup Designer ACT ill Steven W. Bryant Scene1 ChorusMaster The lastevening in Beijing CharlesPrestinari PrtncipalPianist EmilyJarrell Urbanek ProductionStage M anager Mary Yankee Peters Supertitles Thisproduction of Nixon in-Chinais dedicatedto a specialconsortium oTgenerous oonors. RoxanneStouffer Cruz* SanDiego Opera is pleasedto recognizeNuvasive, QUALCOMM and Supertit/e Coordi nators CourtneyAnn Coyle,Attorney at Law as our CorporateProducing CharlesArthur Partnersfor Nixon in China. Marian Porter Sincerethanks also go to SycuanCasino, Phone Etiquette Sponsor and Point Loma NazareneUniversity, Supertitles Sponsor. * SanDiego Opera -

WESTERN CANADA DISTRICT AUDITIONS SUNDAY, DECEMBER 13, 2020 the 2020 National Council Finalists Photo: Fay Fox / Met Opera

NATIONAL COUNCIL 2020–21 SEASON WESTERN CANADA DISTRICT AUDITIONS SUNDAY, DECEMBER 13, 2020 The 2020 National Council Finalists photo: fay fox / met opera CAMILLE LABARRE NATIONAL COUNCIL AUDITIONS chairman The Metropolitan Opera National Council Auditions program cultivates young opera CAROL E. DOMINA singers and assists in the development of their careers. The Auditions are held annually president in 39 districts and 12 regions of the United States, Canada, and Mexico—all administered MELISSA WEGNER by dedicated National Council members and volunteers. Winners of the region auditions executive director advance to compete in the national semifinals. National finalists are then selected and BRADY WALSH compete in the Grand Finals Concert. During the 2020–21 season, the auditions are being administrator held virtually via livestream. Singers compete for prize money and receive feedback from LISETTE OROPESA judges at all levels of the competition. national advisor Many of the world’s greatest singers, among them Lawrence Brownlee, Anthony Roth Costanzo, Renée Fleming, Lisette Oropesa, Eric Owens, and Frederica von Stade, have won National Semifinals the Auditions. More than 100 former auditioners appear appear on the Met roster each season. Sunday, May 9, 2021 The National Council is grateful to its donors for prizes at the national level and to the Tobin Grand Finals Concert Endowment for the Mrs. Edgar Tobin Award, given to each first-place region winner. Sunday, May 16, 2021 Support for this program is generously provided by the Charles H. Dyson National Council The Semifinals and Grand Finals are Audition Program Endowment Fund at the Metropolitan Opera. currently scheduled to take place at the Met.