" the Seventh Seal."

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Rape and the Virgin Spring Abstract

Silence and Fury: Rape and The Virgin Spring Alexandra Heller-Nicholas Abstract This article is a reconsideration of The Virgin Spring that focuses upon the rape at the centre of the film’s action, despite the film’s surface attempts to marginalise all but its narrative functionality. While the deployment of this rape supports critical observations that rape on-screen commonly underscores the seriousness of broader thematic concerns, it is argued that the visceral impact of this brutal scene actively undermines its narrative intent. No matter how central the journey of the vengeful father’s mission from vengeance to redemption is to the story, this ultimately pales next to the shocking impact of the rape and murder of the girl herself. James R. Alexander identifies Ingmar Bergman’s The Virgin Spring as “the basic template” for the contemporary rape-revenge film[1 ], and despite spawning a vast range of imitations[2 ], the film stands as a major entry in the canon of European art cinema. Yet while the sumptuous black and white cinematography of long-time Bergman collaborator Sven Nykvist combined with lead actor Max von Sydow’s trademark icy sobriety to garner it the Academy Award for Best Foreign film in 1960, even fifty years later the film’s representation of the rape and murder of a young girl remain shocking. The film evokes a range of issues that have been critically debated: What is its placement in a more general auteurist treatment of Bergman? What is its influence on later rape-revenge films? How does it fit into a broader understanding of Swedish national cinema, or European art film in general? But while the film hinges around the rape and murder, that act more often than not is of critical interest only in how it functions in these more dominant debates. -

Download Date 03/10/2021 11:10:08

Sacred trauma: Language, recovery, and the face of God in Ingmar Bergman's trilogy of faith Item Type Thesis Authors Dyer, Daniel Download date 03/10/2021 11:10:08 Link to Item http://hdl.handle.net/11122/4802 SACRED TRAUMA: LANGUAGE, RECOVERY, AND THE FACE OF GOD IN INGMAR BERGMAN’S TRILOGY OF FAITH A THESIS Presented to the Faculty of the University of Alaska Fairbanks in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of MASTER OF ARTS By Daniel Dyer, B.A. Fairbanks, Alaska December 2014 Abstract This thesis examines the three films that constitute director Ingmar Bergman’s first trilogy, Through a Glass Darkly , Winter Light , and The Silence. In the thesis I take a multi- disciplinary approach to analyzing the films’ treatments of language, trauma, and God. Drawing on the Old Testament and work of psychoanalysts dealing with trauma, I argue for the similarities and reciprocity between trauma and communion with God and the ways in which the three films illustrate these relationships. Each film functions on a reflexive level to criticize the tools of filmmaking—images, dialog, and narrative—and points to discordance between symbols and reality. Bringing in Jacques Lacan’s model of the imaginary and symbolic orders, I analyze the treatment of language and trauma in the trilogy and the potential for recovery suggested by the end of each film. The thesis culminates by tracing the trilogy toward a new vision of God and his role in the human psyche. v For Grandpa, the Eucharistic Minister. vi Table of Contents Signature Page ......................................................................................................................... -

The Seventh Seal : a Film

Ingmar Bergman Bergman, Ingmar zhlfs Seventh seal 3 1111 00826 2857 791 o 437 BERGMAN SAUSALITO PUBLIC LIBRARY DATIEDUE - NOV <J4 2006 DEMCO, INC. 38-2931 ..... •ft fill M ^T LJ ^r z •**«**. ^m j£ ~ mm mm B3^ + ; %-*.£!* MODERN /film SCRIPTS THE SEVENTH SEAL a Tim by Ingmar Bergman translated from the Swedish by Lars Malmstrom and David Kushner Lorrimer Publishing, London All rights reserved including the right of reproduction in whole or in part in any form English translation copyright © I960 by Ingmar Bergman Original Swedish language film entitled Det Sjunde Inseglet © 1956 by Ingmar Bergman Published by Lorrimer Publishing Limited 47 Dean Street, London Wl First printing 1968 Second printing 1970 Third printing 1973 Fourth printing 1975 SBN paper 900855 22 3 SBN cloth 900855 23 1 This edition is not for sale in the United States of America, its territories, possessions, protectorates, mandated territories, the Philippines or the Dominion of Canada Manufactured in Great Britain by Villiers Publications Ltd, London NW5 The publishers wish to express their gratitude for the help and co- operation received from the staff of Janus Films, Inc., particularly Cyrus Harvey Jr., and also Peter Cowie and the British Film Institute Note : The screenplay in this book is identical to that used by Ingmar Bergman when filming, except that: (1) the original script contains numbers before each sequence which indicate the estimated number of shots that will be necessary for that sequence; (2) since this screen- play is prepared before shooting begins, it contains sequences and dialogue which do not appear in the final film; Bergman has deleted some material to make the published script conform to the film. -

The Films of Ingmar Bergman Jesse Kalin Frontmatter More Information

Cambridge University Press 0521380650 - The Films of Ingmar Bergman Jesse Kalin Frontmatter More information The Films of Ingmar Bergman This volume provides a concise overview of the career of one of the modern masters of world cinema. Jesse Kalin defines Bergman’s conception of the human condition as a struggle to find meaning in life as it is played out. For Bergman, meaning is achieved independently of any moral absolute and is the result of a process of self-examination. Six existential themes are explored repeatedly in Bergman’s films: judgment, abandonment, suffering, shame, a visionary picture, and above all, turning toward or away from others. Kalin examines how Bergman develops these themes cinematically, through close analysis of eight films: well-known favorites such as Wild Strawberries, The Seventh Seal, Smiles of a Summer Night, and Fanny and Alexander; and im- portant but lesser-known works, such as Naked Night, Shame, Cries and Whispers, and Scenes from a Marriage. Jesse Kalin is Andrew W. Mellon Professor of Humanities and Professor of Philosophy at Vassar College, where he has taught since 1971. He served as the Associate Editor of the journal Philosophy and Literature, and has con- tributed to journals such as Ethics, American Philosophical Quarterly, and Philosophical Studies. © Cambridge University Press www.cambridge.org Cambridge University Press 0521380650 - The Films of Ingmar Bergman Jesse Kalin Frontmatter More information CAMBRIDGE FILM CLASSICS General Editor: Ray Carney, Boston University The Cambridge Film Classics series provides a forum for revisionist studies of the classic works of the cinematic canon from the perspective of the “new auterism,” which recognizes that films emerge from a complex interaction of bureaucratic, technological, intellectual, cultural, and personal forces. -

The Life and Films of the Last Great European Director

Macnab-05480001 macn5480001_fm May 8, 2009 9:23 INGMAR BERGMAN Macnab-05480001 macn5480001_fm May 19, 2009 11:55 Geoffrey Macnab writes on film for the Guardian, the Independent and Screen International. He is the author of The Making of Taxi Driver (2006), Key Moments in Cinema (2001), Searching for Stars: Stardom and Screenwriting in British Cinema (2000), and J. Arthur Rank and the British Film Industry (1993). Macnab-05480001 macn5480001_fm May 8, 2009 9:23 INGMAR BERGMAN The Life and Films of the Last Great European Director Geoffrey Macnab Macnab-05480001 macn5480001_fm May 8, 2009 9:23 Sheila Whitaker: Advisory Editor Published in 2009 by I.B.Tauris & Co Ltd 6 Salem Road, London W2 4BU 175 Fifth Avenue, New York NY 10010 www.ibtauris.com Distributed in the United States and Canada Exclusively by Palgrave Macmillan 175 Fifth Avenue, New York NY 10010 Copyright © 2009 Geoffrey Macnab The right of Geoffrey Macnab to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted by him in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988. All rights reserved. Except for brief quotations in a review, this book, or any part thereof, may not be reproduced, stored in or introduced into a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior written permission of the publisher. ISBN: 978 1 84885 046 0 A full CIP record for this book is available from the British Library A full CIP record is available from the Library of Congress Library of Congress -

THE SEVENTH SEAL 1958 92 Min

April 15, 2008 (XVI:14) Ingmar Berman THE SEVENTH SEAL 1958 92 min. Directed and written by Ingmar Bergman Produced by Allan Ekelund Original Music by Erik Nordgren Cinematography by Gunnar Fischer Film Editing by Lennart Wallén Production Design by P.A. Lundgren Gunnar Björnstrand...Jöns, squire Bengt Ekerot...Death Nils Poppe...Jof Max von Sydow...Antonius Block Bibi Andersson...Mia, Jof's wife Inga Gill...Lisa, blacksmith's wife Maud Hansson...Witch Inga Landgré...Karin, Block's Wife Gunnel Lindblom...Girl Bertil Anderberg...Raval Anders Ek...The Monk Åke Fridell...Blacksmith Plog Gunnar Olsson...Albertus Pictor, Church Painter Erik Strandmark...Jonas Skat INGMAR BERGMAN (14 July 1918, Uppsala, Uppsala län, Sweden—30 July 2007,Fårö, Gotlands län, Sweden ) directed 61 films and wrote 63 screenplays. (Bio from WorldFilms.com) "Universally regarded as one of the great masters of modern cinema, Bergman has often concerned himself with spiritual and realized in this cinematic signature. Of the early period, WILD psychological conflicts. His work has evolved in distinct stages STRAWBERRIES stands out for its narrative invention in a fluid over four decades, while his visual style—intense, intimate, manipulation of flashbacks, reveries and dream sequences. Its complex—has explored the vicissitudes of passion with a penetrating psychological investigation of the closing of the life mesmerizing cinematic rhetoric. His prolific output tends to return cycle established Bergman's preoccupation with the relationship to and elaborate on recurrent images, subjects and techniques. between desire, loss, guilt, compassion, restitution and Like the Baroque composers, Bergman works on a small scale, celebration. SAWDUST AND TINSEL (1953)/NAKED NIGHT, finding invention in theme and variation. -

101 Films for Filmmakers

101 (OR SO) FILMS FOR FILMMAKERS The purpose of this list is not to create an exhaustive list of every important film ever made or filmmaker who ever lived. That task would be impossible. The purpose is to create a succinct list of films and filmmakers that have had a major impact on filmmaking. A second purpose is to help contextualize films and filmmakers within the various film movements with which they are associated. The list is organized chronologically, with important film movements (e.g. Italian Neorealism, The French New Wave) inserted at the appropriate time. AFI (American Film Institute) Top 100 films are in blue (green if they were on the original 1998 list but were removed for the 10th anniversary list). Guidelines: 1. The majority of filmmakers will be represented by a single film (or two), often their first or first significant one. This does not mean that they made no other worthy films; rather the films listed tend to be monumental films that helped define a genre or period. For example, Arthur Penn made numerous notable films, but his 1967 Bonnie and Clyde ushered in the New Hollywood and changed filmmaking for the next two decades (or more). 2. Some filmmakers do have multiple films listed, but this tends to be reserved for filmmakers who are truly masters of the craft (e.g. Alfred Hitchcock, Stanley Kubrick) or filmmakers whose careers have had a long span (e.g. Luis Buñuel, 1928-1977). A few filmmakers who re-invented themselves later in their careers (e.g. David Cronenberg–his early body horror and later psychological dramas) will have multiple films listed, representing each period of their careers. -

Philosophical Themes in the Films of Ingmar Bergman Et Al

Philosophical Themes in the Films of Ingmar Bergman et al Fall 2017 Honors 362-01 MWF 11-11:50am; DH 146 Prerequisite: acceptance into the University Honors Program, or consent of instructor. 3 credits. Also counts for 7AI, 7SI, 7VI. Instructor: Charles Webel, Ph.D. Delp-Wikinson Chair and Professor, Peace Studies. Roosevelt Hall 253. email: [email protected] Office Hours: Mon/Wed/Fr 1:00-2:20pm, & by appointment Catalog Description The films of Ingmar Bergman offer a range of jumping-off points for some traditional debates in philosophy in areas such as the philosophy of religion, ethics, and value theory more broadly. Bergman’s oeuvre also offers an entry point for a critical examination of existentialism. This course will investigate some of the philosophical questions posed and positions raised in these films within an auteurist framework. We will also examine the legitimacy of the auteurist framework for film criticism and the representational capacity of film for presenting philosophical arguments. Course Learning Outcomes Upon completion of this course, students will have: a. Understood a range of philosophical positions within the tradition of Western philosophy in general and the intellectual movement called “existentialism” in particular. b. Engaged in a critical analysis of Bergman’s relationship to existentialism, based on synthesizing individual arguments and positions presented throughout his oeuvre. c. Engaged in critical analyses of various philosophical themes, traditions, and problematics, especially ethics, epistemology, philosophical psychology, and political philosophy. d. Understood arguments for and against the capacity of film to present philosophical arguments, focusing on the films of Ingmar Bergman, as well as selected films by other great directors. -

Music As Spiritual Metaphor in the Cinema of Ingmar Bergman

Music as Spiritual Metaphor in the Cinema of Ingmar Bergman By Michael Bird Spring 1996 Issue of KINEMA SECRET ARITHMETIC OF THE SOUL: MUSIC AS SPIRITUAL METAPHOR IN THE CINEMA OF INGMAR BERGMAN Prelude: General Reflections on Music and the Sacred: It frequently happens that in listening to a piece of music we at first do not hear the deep, fundamental tone, the sure stride of the melody, on which everything else is built... It is only after we have accustomed our ear that we find law and order, and as with one magical stroke, a single unified world emerges from the confused welter of sounds. And when this happens, we suddenly realize with delight and amazement that the fundamental tone was also resounding before, that all along the melody had been giving order and unity... - Rudolf Bultmann(1) I said to myself, it is as if the eternal harmony were conversing within itself, as it may have done in the bosom of God just before the Creation of the world. So likewise did it move in my inmost soul. - Goethe(2) One Sunday in December, I was listening to Bach’s Christmas Oratorio in Hedvig Eleonora Church... The chorale moved confidentially through the darkening church: Bach’s piety heals the torment of our faithlessness... - Ingmar Bergman(3) Ingmar Bergman has frequently indicated the immense significance of musical experience for his own personal and artistic development, just as he has also suggested that human existence at large has need for music. His words suggest that of all arts, music may be the most spiritually meaningful of all. -

BERGMAN, ANTONIONI, FELLINI.Pdf

BERGMAN, ANTONIONI, FELLINI By Michael Ventura August 17, 2007 “The death of an artist is quite unassailable,” wrote Lawrence Durrell, adding: “One can only smile and bow.” And after one has smiled and bowed? When two master directors, who once shook my life to the core – Ingmar Bergman and Michelangelo Antonioni – died on the same day, July 30, it felt as though something needed doing, some observance needed to be observed. And their deaths brought up another, Federico Fellini’s in 1993. I hadn’t watched their films in a long while, so my observance (and I heartily recommend it) consisted of observing, watching, in no special order: Fellini’s La Dolce Vita and 8½; Antonioni’s The Passenger, Blow-Up, and L’Avventura; Bergman’s The Seventh Seal, Wild Strawberries, Winter Light, Summer Interlude, Autumn Sonata and Persona -- experiencing all the while a state that my friend Evann DeMario described last summer, “Great art makes you feel that you’re being interrogated.” She meant that in a good way. To have one’s sense of beauty interrogated, as it were, by the extraordinary visual intelligence of these artists. To have one’s spirituality interrogated by down-to-earth souls who struggled with whether spirituality was even possible to an honest person anymore, and who accepted no obvious or whimsical answers. To have one’s vitality, one’s capacity for rich living, interrogated by questioners who refuse to accept irony in place of meaning. To have our era interrogated by another, stripping today’s preoccupations bare, right down to the essence of what we used to call “the human condition.” Beautiful and difficult awakenings await you. -

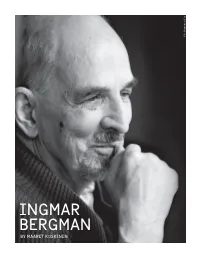

Ingmar Bergman by Maaret-Koskinen English.Pdf

Foto: Bengt Wanselius Foto: INGMAR BERGMAN BY MAARET KOSKINEN Ingmar Bergman by Maaret Koskinen It is now, in the year of 2018, almost twenty years ago that Ingmar Bergman asked me to “take a look at his hellofamess” in his private library at his residence on Fårö, the small island in the Baltic Sea where he shot many of his films from the 1960s on, and where he lived until his death in 2007, at the age of 89. S IT turned out, this question, thrown foremost filmmaker of all time, but is generally re Aout seemingly spontaneously, was highly garded as one of the foremost figures in the entire premeditated on Bergman’s part. I soon came to history of the cinematic arts. In fact, Bergman is understand that his aim was to secure his legacy for among a relatively small, exclusive group of film the future, saving it from being sold off to the highest makers – a Fellini, an Antonioni, a Tarkovsky – whose paying individual or institution abroad. Thankfully, family names rarely need to be accompanied by a Bergman’s question eventually resulted in Bergman given name: “Bergman” is a concept, a kind of “brand donating his archive in its entirety, which in 2007 name” in itself. was added to the UNESCO World Heritage List, and the subsequent formation of the Ingmar Bergman Bergman’s career as a cinematic artist is unique in Foundation (www.ingmarbergman.se). its sheer volume. From his directing debut in Crisis (1946) to Fanny and Alexander (1982), he found time The year of 2018 is also the commemoration of to direct more than 40 films, including some – for Bergman’s birth year of 1918. -

HISTORY of EUROPEAN FILM DIS Fall 2016, European Humanities 3 Credit Course Tuesdays and Fridays, 10:05 – 11:25, Classroom V7-31

Final Syllabus HISTORY OF EUROPEAN FILM DIS Fall 2016, European Humanities 3 Credit Course Tuesdays and Fridays, 10:05 – 11:25, Classroom V7-31 Advertisement for Nordisk Films Co., the Danish film production company which was founded November 6, 1906. Nordisk Film is the world's oldest film production company still in existence. History of European Film | DIS – Study Abroad in Scandinavia | Related Disciplines: Final Syllabus Instructor: Anne Jespersen Cand.mag. (English Literature, Film History and Theory, University of Copenhagen, 1982.) Editor of the film yearbook "Filmsæsonen" 1985-99. Bookpublisher (Forlaget April) 1985-94. Has translated several books and written film reviews and filmhistorical articles. Assistant Professor at the Department of Film & Media Studies, Copenhagen University. Has frequently lectured at The European Film College in Ebeltoft, at Hamburg Media School and at other universities abroad. With DIS since 1987. Anne Jespersen DIS contacts: European Humanities Assistant Program Director, Karen Louise Grova Søilen European Humanities Program Assistant, Matt Kelley Content: The course offers an introduction to film understanding, the elements of film language, film aesthetics, and film history in general as a basis for an analysis of European cinema. Following an introduction to early European film history, the course will concentrate on Italian Neorealism, Masters of Scandinavian Cinema, French New Wave, Masters of Experiment and Modernism, European Cinema of the 1970's, 1980's, 1990's and 2000's. Examples from the American film history will be investigated as comparison. The main emphasis will be on seeing and understanding films and film makers in relation to their historical, literary, and motion picture backgrounds, partly through film examples, partly through reading material.