Author Abstract

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

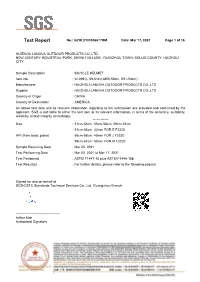

Test Report No.: GZHL2103006677HM Date: Mar 17, 2021 Page 1 of 16

Test Report No.: GZHL2103006677HM Date: Mar 17, 2021 Page 1 of 16 HUIZHOU LANOVA OUTDOOR PRODUCTS CO.,LTD NEW CENTURY INDUSTRIAL PARK, SHENLI VILLAGE, YUANZHOU TOWN, BOLUO COUNTY, HUIZHOU CITY Sample Description : BICYCLE HELMET Item No. : W-099 (L 59-61cm,M55-58cm, S51-54cm) Manufacturer : HUIZHOU LANOVA OUTDOOR PRODUCTS CO.,LTD Supplier : HUIZHOU LANOVA OUTDOOR PRODUCTS CO.,LTD Country of Origin : CHINA Country of Destination : AMERICA As above test item and its relevant information regarding to the submission are provided and confirmed by the applicant. SGS is not liable to either the test item or its relevant information, in terms of the accuracy, suitability, reliability or/and integrity accordingly. ************ Size : 51cm-54cm, 55cm-58cm, 59cm-61cm : 51cm-54cm: 42mm FOR E F2220 HPI (from basic plane) 55cm -58cm: 45mm FOR J F2220 59cm -61cm: 50mm FOR M F2220 Sample Receiving Date : Mar 05, 2021 Test Performing Date : Mar 0 5, 2021 to Mar 17, 2021 Test Performed : ASTM F1 447-18 plus ASTM F1446-15b Test Result(s) : For further details, please refer to the following page(s) Signed for and on behalf of SGS-CSTC Standards Technical Services Co., Ltd. Guangzhou Branch ————————————— Arthur Mak Authorized Signatory Test Report No.: GZHL2103006677HM Date: Mar 17, 2021 Page 2 of 16 Number of Tested Sample: 8 piece(s) / size / headform Test Conducted: Based on ASTM F1447-18 Standard Specification for Helmets Used in Recreational Bicycling or Roller Skating. Test Results: Details shown as following table Clause Test Item / Test Requirement / Test Method Test Result Projections Any unfaired projection extending more than 7 mm from the helmet’s outer surface shall break away or collapse when impacted with forces equivalent to those produced 8.2 Pass by applicable impact-attenuation tests in Section 5. -

City of Ann Arbor Parks & Recreation Open Space Plan

CITY OF ANN ARBOR PARKS & RECREATION OPEN SPACE PLAN SURVEY RESPONSES 2011 - 2015 Question #1 asked how important are parks and recreation in Ann Arbor to quality of life? How important are parks and recreation in Ann Arbor to your quality of life? Response Response Answer Options Percent Count Not at all important 1.0% 10 Somewhat important 10.3% 105 Extremely important 88.5% 904 Not applicable 0.3% 3 answered question 1022 skipped question 12 How important are parks and recreation in Ann Arbor to your quality of life? 1.0% 0.3% Not at all 10.3% N/A Important Somewhat Important Not at all important Somewhat important Extremely important Not applicable 88.5% Extremely Important Question #2 asked in which recreation activities or programs do the respondent or family members regularly participate? In which recreation activities or programs do you or members of your family regularly participate (i.e. more than 5 times per season)? Please keep in mind spring, summer, fall and winter activities. Response Response Answer Options Percent Count Baseball 8.7% 90 Basketball 8.3% 86 Bicycling on unpaved trails (mountain 28.2% 291 bicycling) Bicycling on paved trails or roads 60.7% 626 Canoeing 31.9% 329 Dance 6.0% 62 Day Camp 8.8% 91 Dirt Biking/Jump Courses 4.4% 45 Disc Golf 9.0% 93 Exercise Classes 14.8% 153 Exercise with Dog 29.1% 300 Fishing 8.7% 90 Football 2.7% 28 Foot Golf 1.5% 15 Golfing 11.3% 117 Hiking/Walking 79.0% 814 Hockey 8.1% 83 Ice Skating 18.2% 188 Kayaking 31.9% 329 Martial Arts 2.2% 23 Nature Appreciation (birding, wildlife 54.3% -

Skateboard Ordinance

CHAPTER 16 ADOPTED 03-08-04 AMENDED 07-18-05 Town of Farmington Roller Skating, Skateboarding, and Scooter Riding Ordinance 16-1.1 Title and Authority. This Ordinance shall be known as the Town of Farmington Roller Skating, Skateboarding, and Scooter Riding Ordinance. This Ordinance is enacted pursuant to the Home Rule power granted in the Maine Constitution, and 30-A MRSA 3001 et. seq. 16-1.2 Purpose. Roller-skating, skateboarding and scooter riding are dangerous activities when conducted on streets, sidewalks, and in public areas in a reckless or hazardous manner. The purpose of this Ordinance is to protect the public health and welfare by prohibiting roller-skating, skateboarding, and scooter riding on certain streets, sidewalks, and public areas within the municipality of Farmington. 16-1.3 Definitions. a. Public Area - includes all publicly owned or leased parking lots and Meetinghouse Park. b. Roller Skate – a shoe with a set of wheels attached for skating over a hard surface. c. Scooter – a foot operated vehicle consisting of a narrow footboard mounted between two wheels tandem with an upright steering handle attached to the front wheel. d. Sidewalk - a space adjacent to a street or highway with a built up curb or grass strip that separates the space from the street or highway, designed exclusively for use by pedestrians. e. Skateboard - a single platform which is mounted on wheels, having no mechanism or other device with which to power, steer, or control the direction of movement thereof while being used, operated, or ridden. f. Streets - includes all streets, highways, roads, avenues, lanes, alleyways, or other public rights-of-way used for the passage of motor vehicles. -

Inline Skating Safety

Inline Skating Safety The latest innovation in roller skating is inline skating. [*NOTE: Although many people know the sport as "rollerblading," the term Rollerblade® is a registered trademark of Rollerblade, Inc., and should not be used as a generic term for the sport. Accordingly, this document will refer to the equipment and sport by the generic terms "inline skates" and "inline skating," respectively.] In 1980, inline skates were an ideal off-season training tool for hockey players. Inline skating spread from hockey players to skiers, who also used them for training, and then into the general population of fitness buffs and recreational sports consumers. Swiftly gaining in popularity, rapid inline skating can burn as many calories per minute as cycling or running. Its low-impact, gliding strokes apply less injury-causing stress to the lower body joints than other sports such as aerobics or tennis. Ankles are well- protected because the boots are a heavy, thick plastic and rise above the ankle. • According to the Consumer Product Safety Commission, as many as two-thirds of inline skaters do not wear safety gear. • The Consumer Product Safety Commission estimates that from 2003 to 2007 an average of 32,585 inline skating injuries occurred per year. • Inline skaters should always wear safety gear, including a helmet, knee and elbow pads, and wrist guards. • Just as you would wear a helmet while bicycling, you should wear a helmet when inline skating. • Helmets SIGNIFICANTLY reduce head and brain injury! Since unintentional injuries can occur to even the most experienced inline skaters, the National Safety Council recommends these skating safety tips: • Always wear protective equipment: elbow and knee pads, light gloves, helmets, and wrist guards. -

Chapter 430 BICYCLES, SKATEBOARDS and ROLLER SKATES

Chapter 430 BICYCLES, SKATEBOARDS AND ROLLER SKATES § 430.01. Definitions. [Ord. No. 458, passed 2-25-1991; Ord. No. 535, passed 7-8-1996] The following words, when used in this chapter, shall have the following meanings, unless otherwise clearly apparent from the context: (a) BICYCLE — Shall mean any wheeled vehicle propelled by means of chain driven gears using footpower, electrical power or gasoline motor power, except that vehicles defined as "motorcycles" or "mopeds" under the Motor Vehicle Code for the State of Michigan shall not be considered as bicycles under this chapter. This definition shall include, but not be limited to, single-wheeled vehicles, also known as unicycles; two-wheeled vehicles, also known as bicycles; three-wheeled vehicles, also known as tricycles; and any of the above-listed vehicles which may have training wheels or other wheels to assist in the balancing of the vehicle. (b) SKATEBOARD — Shall include any surfboard-like object with wheels attached. "Skateboard" shall also include, under its definition, vehicles commonly referred to as "scooters," being surfboard-like objects with wheels attached and a handle coming up from the forward end of the surfboard area. (c) ROLLER SKATES — Shall include any shoelike device with wheels attached, including, but not limited to, roller skates, in-line roller skates and roller blades. § 430.02. Operation upon certain public ways prohibited; sails and towing prohibited. [Ord. No. 458, passed 2-25-1991; Ord. No. 677, passed 12-8-2003] (a) No person shall ride or in any manner use a skateboard, roller skate or roller skates upon the following public ways: (1) U.S. -

Barbershop Quartet Contest

INDEX- 1956 (Jan. to June) Barbershop Quartet Contest Bays5^e Dock Reconstruction paeh Release Bicycle Paths Boxing Tournament (amateur) Brooklyn Polytechnic Institute (commencement address) Central Park Pony Track Concerts - City Symphony Orchestra, Naumburg Cromwell Recreation Center Dancing - Music - Square dancing- Brooklyn Dance Festival Egg Rolling Contest Fishing - A & S, Nathan's Flushing Meadow City Bldg. - ice skating ,--• " " Remodelled Boathouse Golf Courses .4 ~ ;->> Gowanus Parkway Lasker Plantings "Learn to Swim Campaign" Irving & Istelle Levy Foundation Magic Entertainers - FAME Marble Shooting Contest Marionette Shows National Tennis Week 22 Tears Park Progress Playgrounds - Van Toorhees #659 - #660 to #6^7 Rockaway Bsnch Opening Celebration St. John's Recreation Center St. Mary's " " Shakespeare Festival Softball Tournament Springtime Plantings Tavern-on-the Green Tennis Courts opening - playing permits * Wollman - Ice skating DEPARTMEN O F PA RKS ARSENAL, CENTRAL PARK 4-1000 FOR R E L E A S Saturday, Juna 9th, 1956. l-l-l-30H-915094(54) <^^fc> 114 The 22nd Annual Barber Shop Quartet Contest Finals conducted by the Park Department will be held on Kfonday evening June 11th 1956 at the Mall in Central Park. The competing quartets were selected in elimination contests held in the five boroughs. The finalists are com- peting for the City championships.First, second and third place win- r ners will receive awards. U*> I rijig 'the turn of the century, when the art of Barber Shop inging made it's greatest contribution to the social life of the community. The following rules will govern this contest: Each quartet may sing two numbers; two medleys or a combination of one song and one medley of the American ballad or barber shop variety. -

High Adventure Application

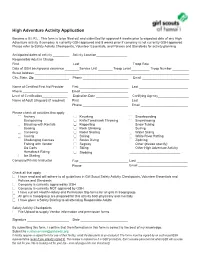

High Adventure Activity Application Become a G.I.R.L.. This form is to be filled out and submitted for approval 4 weeks prior to expected date of any High Adventure activity if company is currently GSH approved and 8 weeks prior if company is not currently GSH approved. Please refer to Safety Activity Checkpoints, Volunteer Essentials, and Policies and Standards for activity planning. Anticipated dates of activity _________ Activity Location_________________ Responsible Adult in Charge First ___________________________ Last___________________________ Troop Role______________________ Date of GSH background clearance ________Service Unit ________ Troop Level __________ Troop Number _________ Street Address _____________________________________________________________________________________ City, State, Zip ___________________ Phone _________________________ Email __________________________ Name of Certified First Aid Provider First ___________________________ Last ___________________________ Phone _________________________ Email __________________________ Level of Certification ______________ Expiration Date __________________ Certifying Agency_________________ Name of Adult Lifeguard (if required) First ___________________________ Last___________________________ Phone _________________________ Email __________________________ Please check all activities that apply Archery Kayaking Snowboarding Backpacking Knife/Tomahawk Throwing Snowshoeing Bicycling with Rentals Rappelling Snow Tubing Boating Rock Climbing Surfing Canoeing -

SKATEBOARDING and ROLLER SKATING Effective May 5, 2011

SKATEBOARDING AND ROLLER SKATING Effective May 5, 2011 Laguna Beach Municipal Code Chapter 10.15 establishes regulations relating to skateboarding and roller skating Municipal Code Section 10.15.050 provides that the City Council of the City of Laguna Beach may designate specific public property locations at which skateboarding and roller skating shall be prohibited; The City Council of the City of Laguna Beach does hereby prohibit skateboarding and roller skating on the public streets and adjoining public sidewalks at the following locations: 1. Third Street between Park Avenue and Mermaid Street; 2. Diamond Street north of Carmelita Street; 3. Crestview Drive; 4. Temple Hills Drive; 5. Bluebird Canyon Drive, between Morningside Drive and Cress Street; 6. Morningside Drive, between both intersections of Rancho Laguna Road and Bluebird Canyon Drive; 7. Summit Drive, between Katella Street and Bluebird Canyon Drive; and 8. Alta Vista Way, between Bonita Way and Solana Way. MUNICIPAL CODE CHAPTER 10.15 10.15.010 Definitions. For purposes of this chapter, the following words shall be defined as follows: (1) “Roller skate” means any shoe, boot or other footwear, or device that may be attached to the foot or footwear, to which one or more wheels are attached, including wheels that are “in line,” also known as roller blades, for the purposes of moving, rolling or propelling a person, through body movement or gravity, along a sidewalk, pavement or other surface. (2) “Skateboard” means a board or platform of any composition or size to which two or more wheels are attached and which is intended to be ridden or propelled, through body movement or gravity, by one or more persons standing, kneeling or lying upon it, through body movement or gravity, and to which there is not affixed to it any seat or any device or mechanism to turn and control the wheels. -

Aggressive Roller Skating

Table of Contents Part 1 - Introduction to Aggressive Roller Skating 1 Welcome to RollerGirl.ca’s Aggressive Roller Skating 101 1 A) Protective Gear 1 B) Skates 1 C) Know your limits, skate within them 2 D) Park Etiquette 2 E) Your first time 3 F) Falling Safely 4 Part 2 - Transition 6 A) Introduction 6 B) Turning in a transition 6 C) Fakie - skating backwards in transition 9 Part 3 - Dropping In 11 A) Introduction 11 B) Overcoming Fear 11 C) Lean Forward! 11 D) Toe Stopper Drop 12 E) Slide Bar Drop 13 F) Roll In Drop 14 Part 4 - Stalls 15 A) Introduction 15 B) Beginner Backside Stalls 16 C) Backside Stalls 17 D) Frontside Stalls 18 Part 5 - Terminology 19 Table of Contents - www.rollergirl.ca Part 1 - Introduction to Aggressive Roller Skating Welcome to RollerGirl.ca’s Aggressive Roller Skating 101 My name is Lisa Suggitt and I will be your guide as you learn some basic aggressive roller skating skills. I am an avid roller skater and have been skating aggressively for nearly a decade. Over the years, I have introduced many skaters to the joys (and pains) of ramp roller skating. This guide has been a dream of mine for ages and I am really excited that it has finally come to fruition. With it, I hope to make skateparks more accessible and less intimidating to the beginner aggressive skater and to intro- duce the basic skills that are the foundations of all ramp skating. Most of all, I hope to share with you some of my passion and love for the sport. -

Standard Activities Adventure Activities

Standard activities With both our Essential and Premier policies, you’re covered to do the following activities while on a trip. There is no cover under this policy for any sporting activity where money is paid to you to take part, or for any kind of manual work. • Archery • Paintballing if you wear eye protection • Badminton • Parascending or parasailing over water (once only and if fully • Banana boating supervised by a person experienced in this activity) • Baseball • Pony trekking • Basketball • Rambling • Body and boogie boarding • Roller skating and roller-blading • Bowls and bowling • Rowing no more than 3 miles from the mainland • Bungee jump (once only and if fully supervised by a person • Running experienced in this activity) • Safari trekking as part of an organised tour • Cricket • Scuba diving to a depth of 18 metres if you are diving with another • Cruise activities that are organised by the cruise company and take person and you both hold a certificate of proficiency, or you are diving part on the cruise vessel with a qualified instructor in this profession but not within 24 hours of a flight • Curling • Skateboarding if you wear a helmet • Cycling but not BMX or mountainbiking (other than normal road cycling using a mountain bike) or racing • Sledging or sleigh riding if you are a passenger and being pulled by dogs, horses or reindeer • Dinghy sailing no more than 3 miles from the mainland • Snorkelling • Fishing • Softball or rounders • Football (including soccer, 5-a-side, Gaelic, Footbag, Hacky Sack, indoor and beach) • Squash • Go-karting if you wear a helmet and follow the organiser’s guidelines • Swimming no more than 3 miles from the mainland • Golf • Table tennis • Ice skating on a rink and not speed or inline skating • Tennis • Jogging • Trekking, hiking or fell walking up to 2500 metres •Orienteering • Volleyball • Paddle boarding Adventure activities (Premier cover only) With our Premier cover, you’re also covered to do the following activities while on a trip. -

Examples of Physical Activities by Intensity

Examples of Physical Activities by Intensity# Light Activity+ Moderate Activity+ Vigorous Activity+ less than 3.0 METS* less 3.0-6.0 METS* greater than 6.0 METS* (less than 3.5 calories per minute) (3.5 – 7 calories per minute) (more than 7 calories per minute) Casual Walking Brisk walking (3 - 4.5 mph) Race walking (more than 4.5 mph) Walking uphill Jogging/Running Wheeling a wheelchair Hiking Mountain climbing Backpacking Roller skating at leisurely pace Fast pace in-line skating Bicycling less than 5 mph Bicycling 5-9 mph Bicycling more than 10 mph Low impact aerobics High impact aerobics Aqua aerobics Step aerobics Stretching Light calisthenics Vigorous calisthenics Sitting Yoga Karate, judo, tae kwon do, jujitsu Gymnastics Jumping on a trampoline Jumping rope, jumping jacks Light weight training Weight training Circuit weight training Dancing slowly Moderate dancing Vigorous dancing Boxing—punching bag Boxing—sparring Most aerobic machines (e.g., stair Most aerobic machines (e.g., stair climber, elliptical, stationary climber, elliptical, stationary bike)—moderate pace bike)—vigorous pace Leisurely sports (table tennis, Competitive tennis, volleyball, Competitive basketball, soccer, playing catch) badminton, diving football, rugby, kickball, hockey, Floating Recreational swimming lacrosse Boating Canoeing Swimming laps or synchronized Fishing Horseback riding swimming Golf—using cart Golf—carrying clubs Treading water Light yard/house work Housework that involves intense Water jogging scrubbing/cleaning Water polo Shoveling snow Downhill or cross country skiing Carrying a child weighing more than Pushing non-motorized lawnmower 50 pounds Occupations requiring extended Occupations that require an Occupations that require heavy periods of sitting extended amount of time standing lifting or rapid movement or walking Source: U.S. -

THE BICYCLE MAN Might Not Be Able to Actually See the Wheels in All Objects

Brainstorm a list of things that have wheels. Remind the students that they THE BICYCLE MAN might not be able to actually see the wheels in all objects. Categorize the Author: Allen Say items on the list into groups, such as “wheels that move us from place to Publisher: Parnassus Press place,” “wheels that make things work,” “wheels that are used for fun,” etc. As they classify the items, discuss any that could appear on more than one list. THEME: The world is full of wheels doing all kinds of things. Invite a police officer into the classroom to talk with the students about safe bicycle riding, roller blading, and skateboarding. PROGRAM SUMMARY: Invite a person who repairs bicycles into the classroom to talk about keeping In a small village in Japan, two American soldiers do amazing tricks on a bor- a bicycle in good condition and problem areas for young people to watch for rowed bicycle. with their bikes. After the guest has left, brainstorm a safe bicycle checklist. LeVar explores the world of wheels and sees how they keep us rolling along- Duplicate the list for students to take home. from bicycles and skateboards to scooters, rollerblades, and human-powered Have students use their creativity and invent a unique bicycle—one that has vehicles. He talks with a freestyle bike specialist who demonstrates some all sorts of special recreational adaptations attached to it, such as a television stunts, and learns about skateboard features from a pro. set, a case for special books, a soda fountain, a gumball machine, and any- TOPICS FOR DISCUSSION: thing else that is wildly imaginative.