A Brief Review of the Status of Plains Bison in North America JOW, Spring 2006, Vol

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Splendor in the Grass—Daily Itinerar-Y

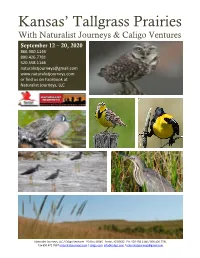

Kansas’ Tallgrass Prairies With Naturalist Journeys & Caligo Ventures September 12 – 20, 2020 866.900.1146 800.426.7781 520.558.1146 [email protected] www.naturalistjourneys.com or find us on Facebook at Naturalist Journeys, LLC Naturalist Journeys, LLC / Caligo Ventures PO Box 16545 Portal, AZ 85632 PH: 520.558.1146 / 800.426.7781 Fax 650.471.7667 naturalistjourneys.com / caligo.com [email protected] / [email protected] Autumn hues and cooler weather make Tour Highlights September an ideal time to experience the ✓ Experience the grandeur and history of natural secrets hidden deep in Kansas’ tallgrass ranching days at the NPS’s Tallgrass Prairie prairies. Witness tens of thousands of acres of Preserve prairie that stretch your imagination and ✓ Learn about the latest research on prairie inspire your heart. Join Naturalist Journeys on ecosystems at Konza Prairie this tallgrass prairie tour to investigate world- class wetlands and grasslands as we explore ✓ Visit the Maxwell Game Wildlife Refuge for a the amazing prairies of central Kansas and the safe encounter with bison and possibly elk Flint Hills ecosystem. This is the only remaining ✓ Search for Burrowing Owl at Cheyenne area in America with intact, extensive tallgrass Bottoms, a Wetland of International prairie landscapes. Importance ✓ Observe raptors, gulls, early migrating September brings fall color and tall, mature waterfowl, shorebirds, and with a bit of luck, grasses decorate the landscape. This is our American White Pelican by the thousands guides’ favorite time to visit. Discover Big- ✓ Explore with local guides, Ed and Sil Pembleton, bluestem, Indiangrass, Switchgrass, and the who have their finger on the pulse of the area, other tall grasses that blanket these hills, and savor late-blooming wildflowers. -

Plains Bison and Wood Bison Conservation in Canada

Bison Conservation in Canada Shelley Pruss Parks Canada Agency Greg Wilson Environment and Climate Change Canada 19 May 2016 1 Canada is home to two subspecies of bison Key morphological differences between Wood Bison bull (Bison bison athabascae) Plains Bison bulls(Bison bison bison) Line drawing courtesy of Wes Olson taken from COSEWIC. 2013. COSEWIC assessment and status report on the Plains Bison (Bison bison bison) and the Wood Bison (Bison bison athabascae) in Canada. 2 PLAINS BISON All wild Plains Bison subpopulations in Canada today are the descendants of approximately 81 ancestors captured in three locations in the 1870s and 1880s, and persist as a tiny fraction of their original numbers (~30 million in North America). WOOD BISON Alaska Dept of Fish and Game Historical (pre-settlement) distribution of Wood Bison and Plains Bison in North America. Modified from Gates et al. (2010). Polygons courtesy of Keith Aune, Wildlife Conservation Society (COSEWIC 3 2013) The Species at Risk Act The federal government is responsible for implementing the federal Species at Risk Act (SARA) • Purpose: to prevent species from being extirpated or becoming extinct and to provide for recovery of species at risk The key provisions of SARA are: • Prohibitions against killing or harming listed species on federal lands • Requirement to develop a national recovery strategy and action plan(s) and to identify critical habitat to the extent possible for Extirpated, Endangered, and Threatened species • Management plans are developed for species of Special -

LANDFIRE Biophysical Setting Model Biophysical Setting: 9814340 Texas-Louisiana Coastal Prairie

LANDFIRE Biophysical Setting Model Biophysical Setting: 9814340 Texas-Louisiana Coastal Prairie This BPS is lumped with: 1487 This BPS is split into multiple models: BpS 1434 is systematically lumped with 1487. BpS 1487 is too fine for mapping and modeling. General Information Contributors (also see the Comments field) Date 1/24/2007 Modeler 1 Chris Harper [email protected] Reviewer Modeler 2 Ron Masters [email protected] Reviewer Modeler 3 Patrick Walther [email protected] Reviewer Vegetation Type Dominant Species Map Zone Model Zone ANGE Upland 98 Alaska Northern Plains Grassland/Herbaceous SCSC California N-Cent.Rockies General Model Sources PAVIS Great Basin Pacific Northwest Literature SPSP Great Lakes South Central Local Data TRDA3 Hawaii Southeast Expert Estimate PAHE2 Northeast S. Appalachians SONU2 Southwest MOCE2 Geographic Range This BpS encompasses non-saline tallgrass prairie vegetation ranging along the coast of LA and TX. This coastal prairie region once covered as much as nine million acres (Grace 2000). The prairie region of southwestern LA was once extensive (~ 2.5 million acres) but today is limited to small, remnant parcels (100-1000ac). Gulf Coast and inland varying distances from 50-150 miles (80-240 km) from south TX to LA and the mouth of the Mississippi River. In LA, it is bordered to the north and east by Southern Floodplain Forest (Kuchler 1964). To the south and west it also joins with the desert grasslands. This BpS is found in MZ37 in ECOMAP subsections 232Ea and 232Eb. Biophysical Site Description This BpS is found on Vertisols and Alfisols which developed over Pleistocene terraces flanking the Gulf Coast. -

The Destruction of the Bison an Environmental History, –

front.qxd 1/28/00 10:59 AM Page v The Destruction of the Bison An Environmental History, 1750–1920 ANDREW C. ISENBERG Princeton University front.qxd 1/28/00 10:59 AM Page vi published by the press syndicate of the university of cambridge The Pitt Building, Trumpington Street, Cambridge, United Kingdom cambridge university press The Edinburgh Building, Cambridge cb2 2ru, uk http://www.cup.cam.ac.uk 40 West 20th Street, New York, ny 10011-4211, usa http://www.cup.org 10 Stamford Road, Oakleigh, Melbourne 3166, Australia Ruiz de Alarcón 13, 28014 Madrid, Spain © Andrew C. Isenberg 2000 This book is in copyright. Subject to statutory exception and to the provisions of relevant collective licensing agreements, no reproduction of any part may take place without the written permission of Cambridge University Press. First published 2000 Printed in the United States of America Typeface Ehrhardt 10/12 pt. System QuarkXPress [tw] A catalog record for this book is available from the British Library. Library of Congress Cataloging in Publication data Isenberg, Andrew C. (Andrew Christian) The destruction of the bison : an environmental history, 1750–1920 / Andrew C. Isenberg. p. cm. – (Studies in environment and history) Includes index. isbn 0-521-77172-2 1. American bison. 2. American bison hunting – History. 3. Nature – Effect of human beings on – North America. I. Title. ql737.u53i834 2000 333.95´9643´0978 – dc21 99-37543 cip isbn 0 521 77172 2 hardback front.qxd 1/28/00 10:59 AM Page ix Contents Acknowledgments page xi Introduction 1 1 The Grassland Environment 13 2 The Genesis of the Nomads 31 3 The Nomadic Experiment 63 4 The Ascendancy of the Market 93 5 The Wild and the Tamed 123 6 The Returns of the Bison 164 Conclusion 193 Index 199 ix intro.qxd 1/28/00 11:00 AM Page 1 Introduction Before Europeans brought the horse to the New World, Native Americans in the Great Plains hunted bison from foot. -

Second Chance for the Plains Bison

ARTICLE IN PRESS BIOLOGICAL CONSERVATION xxx (2007) xxx– xxx available at www.sciencedirect.com journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/biocon Review Second chance for the plains bison Curtis H. Freesea,*, Keith E. Auneb, Delaney P. Boydc, James N. Derrd, Steve C. Forresta, C. Cormack Gatese, Peter J.P. Goganf, Shaun M. Grasselg, Natalie D. Halbertd, Kyran Kunkelh, Kent H. Redfordi aNorthern Great Plains Program, World Wildlife Fund, P.O. Box 7276, Bozeman, MT 59771, USA bMontana Fish, Wildlife & Parks, 1420 E 6th Avenue, Helena, MT 59620, USA cP.O. Box 1101, Redcliff, AB, Canada T0J 2P0 dDepartment of Veterinary Pathobiology, Texas A&M University, College Station, TX 77843-4467, USA eFaculty of Environmental Design, University of Calgary, Calgary, AB, Canada T6G 2E1 fUSGS Northern Rocky Mountain Science Center, P.O. Box 173492, Bozeman, MT 59717-3492, USA gLower Brule Sioux Tribe, Department of Wildlife, Fish and Recreation, P.O. Box 246, Lower Brule, SD 57548, USA hNorthern Great Plains Program, World Wildlife Fund, 1875 Gateway South, Gallatin Gateway, MT 59730, USA iWCS Institute, Wildlife Conservation Society, 2300 Southern Blvd., Bronx, NY 10460, USA ARTICLE INFO ABSTRACT Article history: Before European settlement the plains bison (Bison bison bison) numbered in the tens of mil- Received 30 July 2006 lions across most of the temperate region of North America. Within the span of a few dec- Received in revised form ades during the mid- to late-1800s its numbers were reduced by hunting and other factors 12 November 2006 to a few hundred. The plight of the plains bison led to one of the first major movements in Accepted 27 November 2006 North America to save an endangered species. -

Petition to List Plains Bison As Threatened Under the ESA. James A

Petition to list plains bison as threatened under the ESA. James A. Bailey, PhD. Belgrade, MT [email protected] Summary: I petition to list wild plains bison (Bison bison bison) as threatened under the Endangered Species Act of 1973 (ESA), as amended, in order to conserve the subspecies and the ecosystems upon which plains bison depend. I find that each of the four major ecotypes of plains bison in the United States is likely to become endangered in the foreseeable future and that each ecotype is not sufficiently abundant or distributed, nor properly managed, to fulfill stated purposes of the ESA. While the number of plains bison in wild and conservation herds has not declined in about 70 years, there are numerous threats to the future of wild plains bison that are not apparent in the total number of animals. Wild plains bison are threatened with loss of potential habitat, introgression with cattle genes, loss of genetic diversity, domestication and loss of wildness, disappearance of ecological effectiveness, and lack of effective, coordinated and persistent state and federal programs to restore the subspecies. Should the Fish and Wildlife Service contend that listing plains bison is not warranted, I request that each major ecotype of wild plains bison be listed as threatened, as a significant distinct population segment (DPS), under the ESA in order to conserve the ecotypes and the ecosystems upon which these ecotypes depend. I suggest four major ecotypes of plains bison be considered as significant DPS’s to retain allelic diversity of plains bison in the future, so that bison may again fulfill their evolved ecological role as a keystone interactive species across examples of significant portions of the subspecies’ historic range. -

Plains Bison Bison Bison Bison

COSEWIC Assessment and Status Report on the Plains Bison Bison bison bison in Canada THREATENED 2004 COSEWIC COSEPAC COMMITTEE ON THE STATUS OF COMITÉ SUR LA SITUATION ENDANGERED WILDLIFE DES ESPÈCES EN PÉRIL IN CANADA AU CANADA COSEWIC status reports are working documents used in assigning the status of wildlife species suspected of being at risk. This report may be cited as follows: COSEWIC 2004. COSEWIC assessment and status report on the plains bison Bison bison bison in Canada. Committee on the Status of Endangered Wildlife in Canada. Ottawa. vi + 71 pp. (www.sararegistry.gc.ca/status/status_e.cfm). Production note: COSEWIC would like to acknowledge Greg Wilson and Keri Zittlau for writing the status report on the plains bison Bison bison bison in Canada prepared under contract with Environment Canada. The report was overseen and edited by Marco Festa-Bianchet, the COSEWIC Terrestrial Mammals Species Specialist Co-chair. COSEWIC would like to acknowledge Parks Canada for providing partial funding for the preparation of this report. For additional copies contact: COSEWIC Secretariat c/o Canadian Wildlife Service Environment Canada Ottawa, ON K1A 0H3 Tel.: (819) 997-4991 / (819) 953-3215 Fax: (819) 994-3684 E-mail: COSEWIC/[email protected] http://www.cosewic.gc.ca Ếgalement disponible en français sous le titre Ếvaluation et Rapport de situation du COSEPAC sur le bison des prairies (Bison bison bison) au Canada. Cover illustration: Plains bison — Illustration by Wes Olson. Her Majesty the Queen in Right of Canada 2004 Catalogue No. CW69-14/379-2004E-PDF ISBN 0-662-37298-0 HTML: CW69-14/379-2004E-HTML 0-662-37299-9 Recycled paper COSEWIC Assessment Summary Assessment Summary – May 2004 Common name Plains bison Scientific name Bison bison bison Status Threatened Reason for designation There are currently about 700 mature bison of this subspecies in three free-ranging herds and about 250 semi- captive mature bison in Elk Island National Park. -

Wildlife Notebook Series: American Bison

American Bison The two modern subspecies of North American bison are plains bison (Bison bison bison) and wood bison (Bison bison athabascae). Various forms of bison existed in Alaska for several hundred thousand years, and until recently were one of the most abundant large animals on the landscape. Wood bison were the last subspecies to occur in Alaska and evolved from their larger-horned Pleistocene ancestors. They lived in parts of Interior and Southcentral Alaska for several thousand years before disappearing during the last few hundred years. These animals were an important resource for native peoples who hunted them for their meat and hides. Plains bison occurred in southern Canada and the lower 48 states. This animal shaped the lifestyle of the Plains Indians and figured prominently in American history before they were brought to near extinction by the late 1800s. Nineteen plains bison were transplanted to present day Delta Junction, Alaska from Montana in 1928. Alaska's existing wild bison are descendants of these 19 animals. Transplants have created additional herds at Copper River, Chitina River, and Farewell. Small domestic herds are located in agricultural areas on the mainland and on Kodiak and Popov Islands. There were approximately 700 wild plains bison in the state in 2007. Efforts are underway to restore wood bison to parts of their original range in Alaska. By 1900 there were fewer than 300 wood bison remaining in North America, but conservation efforts in Canada have allowed them to increase and there are now over 4,000 animals in healthy free-ranging herds. The planned reintroduction of wood bison to Alaska could increase this number substantially during the coming decades. -

The North American Bison Dave Arthun and Jerry L

The North American Bison Dave Arthun and Jerry L. Holechek Dept. of Animal and Range Science, New Mexico State University, Las Cruces 88003 Reprinted from Rangelands 4(3), June 1982 Summary Bison played a significant role in the settling of the Western United States and Canada. This article summarizes the major events in the history of bison in North America from the times of the early settlers to the twentieth century. The effect of bison grazing on early rangeland conditions is also discussed. The North American Bison No other indigenous animal, except perhaps the beaver, influenced the pages of history in the Old West as did the bison. The bison's demise wrote the final chapter for the Indian and opened the West to the white man and civilization. The soil-grass-buffalo-lndian relationship had developed over thousands of years, The bison was the essential factor in the plains Indian's existence, and when the herds were destroyed, the Indian was easily subdued by the white man. The bison belongs to the family Bovidae. This is the family to which musk ox and our domestic cattle, sheep, and goats belong. Members have true horns, which are never shed. Horns are present in both sexes. The Latin or scientific name is Bison bison, inferring it is not a true buffalo like the Asian and African buffalo. The true buffalo possess no hump and belong to the genus Bubalus, local venacular for the American bison has included buffalo, Mexican bull, shaggies, and Indian cattle. The bison were the largest native herbivore on the plains of the West. -

Plains Bison Restoration in the Canadian Rocky 25 Mountains? Ecological and Management Considerations CLIFFORD A

Crossing boundaries to restore species and habitats Plains bison restoration in the Canadian Rocky 25 Mountains? Ecological and management considerations CLIFFORD A. WHITE, Banff National Park, Box 900, Banff, Alberta T0l 0C0, Can- ada E. GWYN LANGEMANN, Parks Canada, Western Service Centre, #550, 220 4th Ave- nue SE, Calgary, Alberta T2G 4X3, Canada C. CORMACK GATES, Faculty of Environmental Design, University of Calgary, Cal- gary, Alberta T2N 1N4, Canada CHARLES E. KAY, Department of Political Science, Utah State University, Logan, Utah 84322-0725 TODD SHURY, Banff National Park, Box 900, Banff, Alberta T0l 0C0, Canada THOMAS E. HURD, Banff National Park, Box 900, Banff, Alberta T0l 0C0, Canada Introduction Evaluations of long-term ecosystem states and processes for the Canadian Rockies (Kay and White 1995; Kay et al. 1999; Kay and White, these proceedings) have demonstrated that plains bison (Bison bison) were a significant prehistoric and historic component of Banff National Park’s faunal assemblage. Bison were elimi- nated from most their historic range by human overhunting (Roe 1970). The park management plan (Parks Canada 1997) requires an evaluation of bison restoration (Shury 2000). In this paper we summarize some perspectives on the ecological sig- nificance of bison, potential habitat use and movement patterns, and implications for management. We conclude by describing the ongoing restoration feasibility study process. Bison ecological interactions Bison are the largest North American land mammal and may have had significant ecological effects on ecosystem states and processes where the species occurred. Un- derstanding potential ecological interactions in the Canadian Rockies (Figure 25.1) has provided a focus for interdisciplinary research of archaeologists, anthropologists, and ecologists (Magne et al. -

Reinterpreting the 1882 Bison Population Collapse by Sierra Dawn Stoneberg Holt

Reinterpreting the 1882 Bison Population Collapse By Sierra Dawn Stoneberg Holt Everything from soil erosion to noxious weeds to sage- On the Ground grouse welfare is believed to hinge on range management. • Many people believe grazing management is vital to And at the same time, society is just as strongly invested in ecosystem health. Others feel ecosystems are only the opposite viewpoint, that the finest management is that of healthy when nature takes its course. The Great Mother Nature, unsullied by human involvement. From this Plains bison population of the early 1800s suppos- perspective, every single one of those hours and dollars and edly supports the superiority of goal-free grazing educations and careers is a waste of time and resources and management. directly harmful to the environment. • By 1883, bison were virtually extinct, and hunting is Where I live, this perspective is represented by the Charles usually blamed. However, records indicate that M. Russell National Wildlife Refuge, which changed from hunters killed less than the annual increase each rotated to continuous grazing because water developments year. Evidence implicates disease and habitat and fences are unnatural. It is represented by the American degradation instead. Prairie Reserve, which is petitioning the Bureau of Land • Comparing Allan Savory’s observations in Africa, Management to let it remove interior fences and abandon its Lewis and Clark’s observations in eastern Montana, grazing plan. It is represented by Yellowstone National Park, and Blackfoot history, indications are the bison whose bison herd ballooned to over an order of magnitude disappearance was perhaps triggered by the loss of above official carrying capacity when “natural herd manage- intelligent human management. -

American Bison Table of Contents

American Bison Table of Contents How to Get Started 3 Curriculum Standards (Kansas) 4 Curriculum Standards (National) 5 Lesson A: Bison or Buffalo? 6 Lesson B: Natural History of the Bison 9 Lesson C: Bison and Their Habitat 1 4 Lesson D: American Indians and Bison 1 9 Lesson E: The Early Buffalo Hunt 24 Lesson F: Destruction of the Bison 28 Lesson G: Bison Conservation Efforts 3 5 Post-Trunk Activities 39 References and Additional Resources 40 Inventory 4 1 2 How to Get Started The American bison was the largest mammal living on the largest ecosystem in North America. It dictated the functioning of the prairie ecosystem as well as the functioning of human culture for almost 10,000 years. Over the course of one generation, the animal, the ecosystem, and the human culture were nearly exterminated. Today, the bison is a symbol of the capacity for human destruction but also our efforts to preserve and restore. Materials contained in this kit are geared toward grades 4- 5 and correlated to Kansas State Education Standards for those levels. However, you may use the materials in the trunk and this booklet as you deem appropriate for your students. References to items from trunk will be in bold print and underlined. Graphics with a Figure Number referenced will have accompanying transparencies and digital versions on the CD. Watch for the following symbols to help guide you through the booklet: All questions, com - ments, and suggestions Indicates a class discussion point and potential are welcome and should writing activity. be forwarded to: Education Coordinator Tallgrass Prairie NPRES Indicates further resources on the Web for 2480B Ks Hwy 177 extension learning.