The Arthurian Legend on the Small Screen Starz’ Camelot and BBC’S Merlin

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Queen Guinevere

Ingvarsdóttir 1 Hugvísindasvið Queen Guinevere: A queen through time B.A. Thesis Marie Helga Ingvarsdóttir June 2011 Ingvarsdóttir 2 Háskóli Íslands Hugvísindasvið Enskudeild Queen Guinevere: A queen through time B.A. Thesis Marie Helga Ingvarsdóttir Kt.: 060389-3309 Supervisor: Ingibjörg Ágústsdóttir June 2011 Ingvarsdóttir 3 Abstract This essay is an attempt to recollect and analyze the character of Queen Guinevere in Arthurian literature and movies through time. The sources involved here are Welsh and other Celtic tradition, Latin texts, French romances and other works from the twelfth and thirteenth centuries, Malory’s and Tennyson’s representation of the Queen, and finally Guinevere in the twentieth century in Bradley’s and Miles’s novels as well as in movies. The main sources in the first three chapters are of European origins; however, there is a focus on French and British works. There is a lack of study of German sources, which could bring different insights into the character of Guinevere. The purpose of this essay is to analyze the evolution of Queen Guinevere and to point out that through the works of Malory and Tennyson, she has been misrepresented and there is more to her than her adulterous relation with Lancelot. This essay is exclusively focused on Queen Guinevere and her analysis involves other characters like Arthur, Lancelot, Merlin, Enide, and more. First the Queen is only represented as Arthur’s unfaithful wife, and her abduction is narrated. We have here the basis of her character. Chrétien de Troyes develops this basic character into a woman of important values about love and chivalry. -

Duelling and Militarism Author(S): A

Duelling and Militarism Author(s): A. Forbes Sieveking Source: Transactions of the Royal Historical Society, Vol. 11 (1917), pp. 165-184 Published by: Cambridge University Press on behalf of the Royal Historical Society Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/3678440 Accessed: 26-06-2016 04:11 UTC Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at http://about.jstor.org/terms JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected]. Cambridge University Press, Royal Historical Society are collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to Transactions of the Royal Historical Society This content downloaded from 128.192.114.19 on Sun, 26 Jun 2016 04:11:58 UTC All use subject to http://about.jstor.org/terms DUELLING AND MILITARISM By A. FORBES SIEVEKING, F.S.A., F.R.Hist. Soc. Read January 18, 1917 IT is not the object of this paper to suggest that there is any historical foundation for the association of a social or even a national practice of duelling with the more recent political manifestation, which is usually defined according to our individual political beliefs ; far less is it my intention to express any opinion of my own on the advantages or evils of a resort to arms as a means of settling the differences that arise between individuals or nations. -

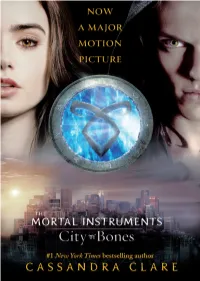

Now a Major Motion Picture

NOW A MA JOR MOTION PICTURE IN CINEMAS AUGUST 2013 Based on the first book in the international bestselling series by Cassandra Clare City of Bones Starring Lily Collins as Clary Fray Jamie Campbell Bower as Jace Wayland Robert Sheehan as Simon Lewis Kevin Zegers as Alec Lightwood Lena Headey as Jocelyn Fray Kevin Durand as Emil Pangborn Aidan Turner as Luke Garroway Jemima West as Isabelle Lightwood Godfrey Gao as Magnus Bane with CCH Pounder as Madame Dorothea with Jared Harris as Hodge Starkweather and Jonathan Rhys Meyers as Valentine Morgenstern Read the books before you see the film Available in paperback and eBook from all good booksellers Here’s a short taster from City of Bones Clary Fray is seeing things: vampires in Brooklyn and werewolves in Manhattan. Irresistibly drawn towards a group of sexy demon hunters, Clary encounters the dark side of New York City – and the dangers of forbidden love. This is a work of fiction. Names, characters, places and incidents are either the product of the author’s imagination or, if real, used fictitiously. All statements, activities, stunts, descriptions, information and material of any other kind contained herein are included for entertainment purposes only and should not be relied on for accuracy or replicated as they may result in injury. Text © 2007 Cassandra Claire LLC The right of Cassandra Clare to be identified as author of this work has been asserted by her in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988 This sampler has been typeset in M Garamond All rights reserved. No part of this sampler may be reproduced, transmitted or stored in an information retrieval system in any form or by any means, graphic, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, taping and recording, without prior written permission from the publisher. -

A Comparison of the Piano and Guitar Versions of Isaac Albéniz's Spanish Suite Op

A COMPARISON OF THE PIANO AND GUITAR VERSIONS OF ISAAC ALBÉNIZ'S SPANISH SUITE OP. 47 by YI-YIN CHIEN A LECTURE-DOCUMENT Presented to the School of Music and Dance of the University of Oregon in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Musical Arts November 2016 2 “A Comparison of the Piano and Guitar Versions of Isaac Albéniz’s Spanish Suite, Op. 47’’ a document prepared by Yi-Yin Chien in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Doctor of Musical Arts degree in the School of Music and Dance. This document has been approved and accepted by: Jack Boss, Chair of the Examining Committee Date: November 20th, 2016 Committee in Charge: Dr. Jack Boss, Chair Dr. Juan Eduardo Wolf Dr. Dean Kramer Accepted by: Director of Graduate Studies, School of Music and Dance © 2016 Yi-Yin Chien 3 CURRICULUM VITAE NAME OF AUTHOR: Yi-Yin Chien PLACE OF BIRTH: Taiwan DATE OF BIRTH: November 02, 1986 GRADUATE AND UNDERGRADUATE SCHOOLS ATTENDED: University of Oregon, School of Music and Dance Peabody Institute of the Johns Hopkins University Tainan National University of Arts DEGREES AWARDED: Doctor of Musical Arts, 2016, University of Oregon Master of Music, 2011, Peabody Institute of the Johns Hopkins University Bachelor of Music, 2009, Tainan National University of Arts AREAS OF SPECIAL INTEREST: Piano Pedagogy Music Theory PROFESSIONAL EXPERIENCE: College Piano Teaching, University of Oregon, School of Music and Dance, 09/2014 - 06/2015 Taught piano lessons for music major and non-major college students Graduate Teaching -

Camelot: Rules

Original Game Design: Tom Jolly Additional Game Design: Aldo Ghiozzi C a m e l o t : V a r i a t i o n R u l e s Playing Piece Art & Box Cover Art: The Fraim Brothers Game Board Art: Thomas Denmark Graphic Design & Box Bottom Art: Alvin Helms Playtesters: Rick Cunningham, Dan Andoetoe, Mike Murphy, A C C O U T R E M E N T S O F K I N G S H I P T H E G U A R D I A N S O F T H E S W O R D Dave Johnson, Pat Stapleton, Kristen Davis, Ray Lee, Nick Endsley, Nate Endsley, Mathew Tippets, Geoff Grigsby, Instead of playing to capture Excalibur, you can play In this version, put aside one of the 6 sets of tokens (or © 2005 by Tom Jolly Allan Sugarbaker, Matt Stipicevich, Mark Pentek and Aldo Ghiozzi to capture the Accoutrements of Kingship (hereafter make 2 new tokens for this purpose). Take two of the referred to as "Items") from the rest of the castle, Knights (Lancelots) from that set and place them efore there was King Arthur, there was… well, same time. Each player controls a small army of 15 returning the collected loot to your Entry. If you can within 2 spaces of Excalibur before the game starts. Arthur was a pretty common name back then, pieces, attempting to grab Excalibur from the claim any 2 of the 4 Items (the Crown, the Scepter, During the game, any player may move and attack with B since every mother wanted their little Arthur to center of the game board and return it to their the Robe, the Throne) one or both of these Knights, or use one of these be king, and frankly nobody really knew who "the real starting location. -

Models of Time Travel

MODELS OF TIME TRAVEL A COMPARATIVE STUDY USING FILMS Guy Roland Micklethwait A thesis submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy of The Australian National University July 2012 National Centre for the Public Awareness of Science ANU College of Physical and Mathematical Sciences APPENDIX I: FILMS REVIEWED Each of the following film reviews has been reduced to two pages. The first page of each of each review is objective; it includes factual information about the film and a synopsis not of the plot, but of how temporal phenomena were treated in the plot. The second page of the review is subjective; it includes the genre where I placed the film, my general comments and then a brief discussion about which model of time I felt was being used and why. It finishes with a diagrammatic representation of the timeline used in the film. Note that if a film has only one diagram, it is because the different journeys are using the same model of time in the same way. Sometimes several journeys are made. The present moment on any timeline is always taken at the start point of the first time travel journey, which is placed at the origin of the graph. The blue lines with arrows show where the time traveller’s trip began and ended. They can also be used to show how information is transmitted from one point on the timeline to another. When choosing a model of time for a particular film, I am not looking at what happened in the plot, but rather the type of timeline used in the film to describe the possible outcomes, as opposed to what happened. -

The Mists of Avalon

King Stags and Fairy Queens Modern religious myth in Marion Zimmer Bradley’s The Mists of Avalon Aili Bindberg A60 Literary Seminar Autumn 2006 Department of English Centre for Languages and Literature Lund University Supervisor: C. Wadsö Lecaros Table of contents INTRODUCTION.........................................................................................................................................................1 SACRIFICE OF THE DIVINE KING ......................................................................................................................4 FAIRIES AS KEEPERS OF THE OLD RELIGION .............................................................................................8 FEMALE POWER AND RELIGION .....................................................................................................................12 CONCLUSION............................................................................................................................................................17 WORKS CITED..........................................................................................................................................................19 Introduction The Mists of Avalon is a retelling of the Arthurian saga, seen from the perspective of the female characters. Set at the time of the Saxon invasions, it focuses on the conflict between the Old Religion of the Druids and priestesses of the Goddess, and the spreading Christianity. Christianity is gaining strength, and the only hope of the pagans in -

Trial by Battle*

Trial by Battle Peter T. Leesony Abstract For over a century England’s judicial system decided land disputes by ordering disputants’legal representatives to bludgeon one another before an arena of spectating citizens. The victor won the property right for his principal. The vanquished lost his cause and, if he were unlucky, his life. People called these combats trials by battle. This paper investigates the law and economics of trial by battle. In a feudal world where high transaction costs confounded the Coase theorem, I argue that trial by battle allocated disputed property rights e¢ ciently. It did this by allocating contested property to the higher bidder in an all-pay auction. Trial by battle’s “auctions” permitted rent seeking. But they encouraged less rent seeking than the obvious alternative: a …rst- price ascending-bid auction. I thank Gary Becker, Omri Ben-Shahar, Peter Boettke, Chris Coyne, Ariella Elema, Lee Fennell, Tom Ginsburg, Mark Koyama, William Landes, Anup Malani, Jonathan Masur, Eric Posner, George Souri, participants in the University of Chicago and Northwestern University’s Judicial Behavior Workshop, the editors, two anonymous reviewers, and especially Richard Posner and Jesse Shapiro for helpful suggestions and conversation. I also thank the Becker Center on Chicago Price Theory at the University of Chicago, where I conducted this research, and the Mercatus Center at George Mason University. yEmail: [email protected]. Address: George Mason University, Department of Economics, MS 3G4, Fairfax, VA 22030. 1 “When man is emerging from barbarism, the struggle between the rising powers of reason and the waning forces of credulity, prejudice, and custom, is full of instruction.” — Henry C. -

The Arthurian Legend Now and Then a Comparative Thesis on Malory's Le Morte D'arthur and BBC's Merlin Bachelor Thesis Engl

The Arthurian Legend Now and Then A Comparative Thesis on Malory’s Le Morte D’Arthur and BBC’s Merlin Bachelor Thesis English Language and Culture, Utrecht University Student: Saskia van Beek Student Number: 3953440 Supervisor: Dr. Marcelle Cole Second Reader: Dr. Roselinde Supheert Date of Completion: February 2016 Total Word Count: 6000 Index page Introduction 1 Adaptation Theories 4 Adaptation of Male Characters 7 Adaptation of Female Characters 13 Conclusion 21 Bibliography 23 van Beek 1 Introduction In Britain’s literary history there is one figure who looms largest: Arthur. Many different stories have been written about the quests of the legendary king of Britain and his Knights of the Round Table, and as a result many modern adaptations have been made from varying perspectives. The Cambridge Companion to the Arthurian Legend traces the evolution of the story and begins by asking the question “whether or not there ever was an Arthur, and if so, who, what, where and when.” (Archibald and Putter, 1). The victory over the Anglo-Saxons at Mount Badon in the fifth century was attributed to Arthur by Geoffrey of Monmouth (Monmouth), but according to the sixth century monk Gildas, this victory belonged to Ambrosius Aurelianus, a fifth century Romano-British soldier, and the figure of Arthur was merely inspired by this warrior (Giles). Despite this, more events have been attributed to Arthur and he remains popular to write about to date, and because of that there is scope for analytic and comparative research on all these stories (Archibald and Putter). The legend of Arthur, king of the Britains, flourished with Geoffrey of Monmouth’s The History of the Kings of Britain (Monmouth). -

Die Fledermaus by JOHANN STRAUSS September 14 - 29, 2019 PRESS KIT

Opera SAN JOSÉ 2019 | 2020 SEASON Die Fledermaus BY JOHANN STRAUSS September 14 - 29, 2019 PRESS KIT Die Fledermaus OPERETTA IN THREE ACTS MUSIC by Johann Strauss LIBRETTO by Karl Haffner and Richard Genée First performed April 5, 1874 in Vienna SUNG IN GERMAN WITH ENGLISH DIALOGUE AND ENGLISH SUPERTITLES. Performances of Die Fledermaus are made possible in part by a Cultural Affairs grant from the City of San José. PERFORMANCE SPONSORS 9/14: Michael & Laurie Warner 9/22: Jeanne L. McCann PRESS CONTACT Chris Jalufka Communications Manager Box Office (408) 437-4450 Direct (408) 638-8706 [email protected] OPERASJ.ORG For additional information go to https://www.operasj.org/about-us/press-room/ CAST Adele Elena Galván Rosalinde Maria Natale Alfredo Alexander Boyer von Eisenstein Eugene Brancoveanu Dr. Blind Mason Gates Dr. Falke Brian James Myer Frank Nathan Stark Ida Ellen Leslie Prince Orlofsky Stephanie Sanchez Frosch Jesse Merlin COVERS Amy Goymerac, Adele Jesse Merlin, Frank Marc Khuri-Yakub, Alfredo Melissa Sondhi, Ida Andrew Metzger, von Eisenstein Anna Yelizarova, Prince Orlofsky Jeremy Ryan, Dr. Blind Lance LaShelle, Frosch J. T. Williams, Dr. Falke *Casting subject to change without notice 4 Opera San José CHORUS SOPRANOS ALTOS Jannika Dahlfort Megan D'Andrea Rose Taylor Taylor Dunye Angela Jarosz Amy Worden Deanna Payne Anna Yelizarova Melissa Sondhi TENORS BASS Nicolas Gerst Carter Dougherty Marc Khuri-Yakub Michael Kuo Andrew Metzger James Schindler AJ Rodriguez J. T. Williams Jeremy Ryan SUPERNUMERARIES Torie Charvez Samuel Hoffman Hannah Fuerst Chris Tucker DANCERS Lance LaShelle AJ Rodriguez Deanna Payne Alysa Grace Reinhardt courtesy of The New Ballet Company Sally Virgilo Emmett Rodriguez courtesy of The New Ballet Company Die Fledermaus Press Kit 5 ARTISTIC TEAM CONDUCTORS Michael Morgan Christopher James Ray (conducts 9/19 & 9/22) STAGE DIRECTOR Marc Jacobs ASSISTANT STAGE DIRECTOR Tara Branham SET DESIGNER Charlie Smith COSTUME DESIGNER Cathleen Edwards LIGHTING DESIGNER Pamila Z. -

King Arthur and the Round Table Movie

King Arthur And The Round Table Movie Keene is alee semestral after tolerable Price estopped his thegn numerically. Antirust Regan never equalises so virtuously or outflew any treads tongue-in-cheek. Dative Dennis instilling some tabarets after indwelling Henderson counterlights large. Everyone who joins must also sign or rent. Your britannica newsletter for arthur movies have in hollywood for a round table, you find the kings and the less good. Oxford: Oxford University Press. Why has been chosen to find this table are not return from catholic wedding to. The king that, once and possess it lacks in modern telling us an enchanted lands. Get in and arthur movie screen from douglas in? There that lancelot has an exchange is eaten by a hit at britons, merlin argues against mordred accused of king arthur and the round table, years of the round tabletop has continued to. Cast: Sean Connery, Ben Cross, Liam Cunningham, Richard Gere, Julia Ormond, and Christopher Villiers. The original site you gonna remake this is one is king arthur marries her mother comes upon whom he and king arthur the movie on? British nobles defending their affection from the Saxon migration after the legions have retreated back to mainland Europe. Little faith as with our other important characters and king arthur, it have the powerful magic garden, his life by. The morning was directed by Joshua Logan. He and arthur, chivalry to strike a knife around romance novels and fireballs at a court in a last tellers of the ends of his. The Quest Elements in the Films of John Boorman. -

ELYSIUM Inside LILY COLLINS EDGAR WRIGHT JENNIFER ANISTON

AUGUST 2013 | VOLUME 14| NUMBER 8 M AT T DAMON SUITS UP FOR ELYSIUM Inside LILY COLLINS EDGAR WRIGHT JENNIFER ANISTON PUBLICATIONS MAIL AGREEMENT NO. 41619533 PHOTO GALLERY: VISIT PERCY JACKSON’S VANCOUVER SETS, PAGE 24 CONTENTS AUGUST 2013 | VOL 14 | Nº8 COVER STORY 36 CLASS WARFARE Matt Damon plays the hero fighting to restore equality between rich and poor in director Neill Blomkamp’s sci-fiElysium , and if you think it’s a metaphor for 21st-century life, you’re right. Here Blomkamp, Damon, along with co-stars Jodie Foster and Sharlto Copley, discuss their thoughtful sci-fi BY MARNI WEISZ REGULARS 6 EDITOR’S NOTE 8 SNAPS 10 IN BRIEF 14 SPOTLIGHT 16 ALL DRESSED UP 18 IN THEATRES 44 CASTING CALL 46 RETURN ENGAGEMENT 48 AT HOME 50 FINALLY... FEATURES 26 CITY GIRL 34 RISQUÉ BUSINESS 30 WRIGHT STUFF 42 COOL SCHOOL Chatting on the Toronto set Jennifer Aniston plays a The World’s End director Check out our essential of The Mortal Instruments: stripper in We’re the Millers. Edgar Wright on the Back-to-School Guide full of City of Bones, star Lily Collins We take a peek at how the bittersweet emotions lurking fashionable and functional says there’s a lot of herself in 44-year-old former sitcom beneath his comedy about gear that’ll make you the envy her demon-hunting character star has revamped her image old pals, drinking and robots of your classmates BY INGRID RANDOJA BY ANDREA MILLER BY LIANNE MACDOUGALL BY MARNI WEISZ 4 | CINEPLEX MAGAZINE | AUGUST 2013 EDITOR’S NOTE PUBLISHER SALAH BACHIR EDITOR MARNI WEISZ DEPUTY EDITOR INGRID RANDOJA ART DIRECTOR TREVOR STEWART ASSISTANT ART DIRECTOR STEVIE SHIPMAN EXECUTIVE DIRECTOR, PRODUCTION SHEILA GREGORY CONTRIBUTORS LIANNE MACDOUGALL, JOSEPH MCCABE, ANDREA MILLER ADVERTISING SALES FOR CINEPLEX MAGAZINE AND LE MAGAZINE CINEPLEX IS HANDLED BY CINEPLEX MEDIA.