Ramcharitmanas

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Plurality of Draupadi, Sita and Ahalya

Many Stories, Many Lessons: The Plurality of Draupadi, Sita and Ahalya Benu Verma Assistant Professor, USHSS Guru Gobind Singh Indraprastha University Dwarka, Delhi Abstract: The relationship between life and literature is a dialogic one. Life inspires literature and literature in turn influences life. Various genres in which literature is manifested reflect on the orientation, significance as well as the place of the text in its social environment. Mikhail Bakhtin proposes that genres dictate the reception of a text. Yet the same text could be interpreted differently in different times and contexts and be rewritten to reflect the aspirations of the author and her/his times. The many life stories of the feminine figures from the epics of Ramayana and Mahabharata assert not only the inconclusive nature of myth and the potency of these epics, they also tell us that with changing political and social milieu the authors reinterpret and record anew given stories to contribute to the literature of their times. Draupadi as the epic heroine of Mahabharata has been written about popularly and widely and in each version with a new take on the major milestones of her life like her five husbands and her birth from fire. The motifs of her disrobing and her hair have been employed variedly to tell various stories, sometimes of oppression and at others of liberation, each belonging to a different time and space. Each story reflected the political stance and aspiration of its author and read by readers differently as per their times and contexts. Through an examination of various literary renditions of the feminine figures from the epics, like Draupadi, Sita, and Ahalya, this paper discusses the relationship between life and literature and how changing times call for changing forms of literature. -

Information to Users

INFORMATION TO USERS This manuscript has been reproduced from the microfihn master. UMI films the text directly from the original or copy submitted. Thus, some thesis and dissertation copies are in typewriter face, while others may be from any type of computer printer. The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality o f the copy submitted. Broken or indistinct print, colored or poor quality illustrations and photographs, print bleedthrough, substandard margins, and improper alignment can adversely afreet reproduction. In the unlikely event that the author did not send UMI a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if unauthorized copyright material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Oversize materials (e.g., maps, drawings, charts) are reproduced by sectioning the original, beginning at the upper left-hand comer and continuing from left to right in equal sections with small overlaps. Each original is also photographed in one exposure and is included in reduced form at the back of the book. Photographs included in the original manuscript have been reproduced xerographically in this copy. Higher quality 6” x 9” black and white photographic prints are available for any photographs or illustrations appearing in this copy for an additional charge. Contact UMI directly to order. UMI A Bell & Howell Information Company 300 North Zed) Road, Ann Arbor Ml 48106-1346 USA 313/76M700 800/521-0600 THE WRITING OF CRISTINA PACHECO: NARRATING THE MEXICAN URBAN EXPERIENCE DISSERTATION Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy in The Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Dawn Slack, M.A. -

Show #1379 --- Week of 6/14/21-6/20/21 HOUR ONE--SEGMENTS 1-3 SONG ARTIST LENGTH ALBUM LABEL___SEGMENT

Show #1379 --- Week of 6/14/21-6/20/21 HOUR ONE--SEGMENTS 1-3 SONG ARTIST LENGTH ALBUM LABEL________________ SEGMENT ONE: "Million Dollar Intro" - Ani DiFranco :55 in-studio n/a "Big Things"-Ted Hawkins 2:45 The Next Hundred Years DGC "Two Step Down To Texas"-Ingram/Lambert/Randall 2:30 The Marfa Tapes RCA "Be Good"-Carsie Blanton 3:30 Love & Rage independent "I’ll Be Your Girl"-The Decemberists 2:35 I’ll Be Your Girl Capitol "Avant Gardener"-Courtney Barnett (in-studio) 3:50 in-studio n/a ***MUSIC OUT AND INTO: ***NATIONAL SPONSOR BREAK*** Nettwerk Records/Old Sea Brigade "Motivational Speaking" (:30) Outcue: " OldSeaBrigade.com." TOTAL TRACK TIME: 19:18 ***PLAY CUSTOMIZED STATION ID INTO: SEGMENT TWO: "Hope"-Arlo Parks (in-studio) 4:30 in-studio n/a ***INTERVIEW & MUSIC: ROSTAM (in California) ("Changephobia," "These Kids We Knew") in-studio interview/performance n/a ***MUSIC OUT AND INTO: ***NATIONAL SPONSOR BREAK*** Leon Speakers/"The Leon Loft" (:30) Outcue: " at LeonSpeakers.com." The Ark/"COVID-19 Slow Return 1" (:30) Outcue: " TheArk.org." TOTAL TRACK TIME: 21:22 SEGMENT THREE: "I Disappear"-Matt The Electrician (SongWriter) 4:30 in-studio independent "Stay Alive"-Mustafa 3:00 When Smoke Rises Young Turks "Know You Got To Run"-Stephen Stills 4:10 Déjà Vu Rhino ***MUSIC OUT AND INTO: ***NATIONAL SPONSOR BREAK*** Nettwerk Records/Beta Radio "Year Of Love" (:30) Outcue: " BetaRadio.com." TOTAL TRACK TIME: 14:19 TOTAL TIME FOR HOUR ONE-54:59 acoustic café · p.o. box 7730 · ann arbor, mi 48107-7730 · 734/761-2043 · fax 734/761-4412 -

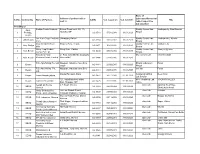

S.L.No. Commodity Name of Packers Address of Packers with E- Mail Id

Name of Address of packers with e- Laboratory/Comercial S.l.No. Commodity Name of Packers CA No. C.A. issued on C.A. valid till TBL mail id /SGL/Cooperative Lab attached R.O.Bhopal Aata, Poddar Foods Products Behind Rewa hotel, NH- 78, Quality Control Lab Vindhyavelly, Maa Birasani 1 Porridge, Shahdol, MP A/2 3518 07.08.2018 31.03.2023 Bhopal Besan Lav Kush Corp. Products Gairatganj, Raisen Quality Control Lab Vindhya velly, Ajiveka 2 Atta Besan A/2-3384 11.10.2013 31.03.2023 Com. Bhopal Maa GAYATRI Flour Khajuria Bina, Dewas Quality control Lab, Vindya Velly 3 Atta, Daliya A/2 3471 15.09.2016 31.03.2021 Mills Bhopal Sironj Crop Produce Sironj Distt- Vidisha Quality Control Lab Sironj & Ajjevika 4 Atta, Besan A/2-3404 03.03.2014 31.03.2019 Comp. Pvt. Ltd Bhopal Kaila Devi Food 21 Ram Janki Mandir Jiwajiganj Morena Ana Lab Chambal Gold 5 Atta, Besan Products Private Limited Morena MP A/2 3464 22/06/2016 31.03.2021 R.B. Agro Milling Pvt. Ltd. Naugaon Industries Area Bina, Bhopal Laboratory Paras 6 Besan A/2-3444 26/06/2015 31/03/2020 Sagar Bhopal R.B. Agro Milling Pvt. Naugoan, Industrial area,Bina own lab Paras 7 Besan A/2-3444 29.05.2015 31.03.2020 Ltd. Mauza Ramgarh, Datia Gwaliar Analytical Deep Gold 8 Besan Tiwari Masala Udyog A/2 3477 14.12.2016 31..03.2021 Lab,Gwaliar 121, Industrial Area, Maksi, MPP. Analytical Lab VINDHYA VALLEY 9 Besan Lakshmi Besan Mill A/2 3476 20.10.2016 31..03.2021 Distt. -

Abstracts Final

Conference on THE RAMAYANA IN LITERATURE, SOCIETY AND THE ARTS February 1-2, 2013 Abstracts published by C.P. R. Institute of Indological Research The C. P. Ramaswami Aiyar Foundation 1, Eldams Road, Chennai 600 018 1 2 CONTENT 1. Tracing the Antiquity of the Ramayana – Through the Inscriptions, literature and Art of the Gupta Period --------------------------------------------------------------------------- 7 Dr. Ashvini Agarwal 2. Plant Diversity in the Valmiki Ramayana ---------------------------------------------------------- 8 M. Amirthalingam 3. The Influence of Ramayana on Kalidasa --------------------------------------------------------- 9 Dr. S. Annapurna 4. Ethical Values of Ramayana ---------------------------------------------------------------------- 11 Dr. V. Balambal 5. Time-honored Depictions of Ramayana in Vidarbha (Maharashtra) during Vakatakas ------13 Kanchana B Bhaisare, B.C. Deotare and P.S. Joshi 6. Highlights from the Chronology of Ayodhya ----------------------------------------------------14 Nicole Elfi and Michel Danino 7. Temples in and around Thanjavur District, in Tamil Nadu connected with Ramayana -------15 Dr. S. Gayathri 8. The Historical Rama ------------------------------------------------------------------------------16 Dr. D.K. Hari and D.K. Hema Hari 9. Historicity of Rawana and Trails of Rama - Seetha in Srilanka --------------------------------23 Devmi Jayasinghe 10. Women in Ramayana - Portrayals, Understandings, Interpretations and Relevance ---------25 Dr. Prema Kasturi 11. Telling or Showing? -

Sita Ram Baba

सीता राम बाबा Sītā Rāma Bābā סִיטָ ה רְ אַמָ ה בָבָ ה Bābā بَابَا He had a crippled leg and was on crutches. He tried to speak to us in broken English. His name was Sita Ram Baba. He sat there with his begging bowl in hand. Unlike most Sadhus, he had very high self- esteem. His eyes lit up when we bought him some ice-cream, he really enjoyed it. He stayed with us most of that evening. I videotaped the whole scene. Churchill, Pola (2007-11-14). Eternal Breath : A Biography of Leonard Orr Founder of Rebirthing Breathwork (Kindle Locations 4961-4964). Trafford. Kindle Edition. … immortal Sita Ram Baba. Churchill, Pola (2007-11-14). Eternal Breath : A Biography of Leonard Orr Founder of Rebirthing Breathwork (Kindle Location 5039). Trafford. Kindle Edition. Breaking the Death Habit: The Science of Everlasting Life by Leonard Orr (page 56) ראמה راما Ράμα ראמה راما Ράμα Rama has its origins in the Sanskrit language. It is used largely in Hebrew and Indian. It is derived literally from the word rama which is of the meaning 'pleasing'. http://www.babynamespedia.com/meaning/Rama/f Rama For other uses, see Rama (disambiguation). “Râm” redirects here. It is not to be confused with Ram (disambiguation). Rama (/ˈrɑːmə/;[1] Sanskrit: राम Rāma) is the seventh avatar of the Hindu god Vishnu,[2] and a king of Ayodhya in Hindu scriptures. Rama is also the protagonist of the Hindu epic Ramayana, which narrates his supremacy. Rama is one of the many popular figures and deities in Hinduism, specifically Vaishnavism and Vaishnava reli- gious scriptures in South and Southeast Asia.[3] Along with Krishna, Rama is considered to be one of the most important avatars of Vishnu. -

Svetasvatara Upanishad

Adhyathma Ramayanam An English Translation by P.R.Ramachander <[email protected] > Vol. 2 Aranya Kandam Kishkinda Kandam Sundara Kandam Edited by T.N.Sethumadhavan <[email protected] > 3. Aranya Kandam (Chapter on forests) Synopsis: (Aranya Kanda is the story of Ramayana , when Rama, Sita and Lakshmana enter the deep forest It starts with the salvation of Virada a Rakshasa , Sara Bhanga a saint, meeting with sages to find out problems , going to hermitage of Sutheeshna who is a disciple of Agasthya, visiting hermitage of Agasthya and taking from him , the Kodanda bow left by Indra, the great prayer of Agasthya, going and settling down in Panchavati where he meets Jatayu, clearing the philosophical doubts of Lakshmana(Rama Gita) , meeting and teasing Soorpanaka the sister of Ravana, cutting off her nose, ears and breats by Lakshmana when she tries to harm Sita, Killing of Khara, Dhooshana and Trisiras and their army of 14000 people in one and half hours, Soorpanaka’s complaint to Ravana suggesting him to kidnap Sita, his visit to Maricha , Rama telling the real Sita to hide in fire and replace herself with a Maya Sita, Rama running to catch the golden deer, the false alam given by Maricha, the kidnapping of Sita, Fight of Jatayu with Rama, Jatayu’s defeat , Rama doing funeral rites to Jatayu and granting him salvation, The prayer of Jatayu, Rama’s giving salvation to Khabanda ,Khabanda’s great prayer , Rama’s meeting with Sabari who gives him hints as to how to proceed further.) Oh girl, oh parrot which is at the top , Who is with -

TOCC0537DIGIBKLT.Pdf

ALEXANDER TCHEREPNIN My Flowering Staff A Volume of Poems by Sergei Gorodetsky Set to Music in a Cycle of 36 Songs for Voice and Piano 1 Epigraph (Op. 17, No. 1) 1:10 2 I O God of days, do not release your violins (Op. 15, No. 3) 1:55 3 II If only I could hear (Op. 15, No. 4) 1:06 4 III I contemplated you, O Andromeda 1:44 5 IV How damned is my beloved life (Op. 15, No. 2) 0:52 6 V The millstones have cooled (Op. 15, No. 5) 1:09 7 VI I love the feminine water 1:10 8 VII Forgive me the enticing mist 1:13 9 VIII Farewell, night! (Op. 15, No. 6) 1:06 10 IX The struggle to voice words (Op. 15, No. 1) 1:10 11 X In agitation, as I touch the morning lyre (Op. 16, No. 2) 1:14 12 XI I am dreaming of the country (Op. 16, No. 5) 1:00 13 XII In the wild forest (Op. 17, No. 2) 1:21 14 XIII My soul is happy to hear 1:24 15 XIV Some of the songs in my soul 1:37 16 XV Perhaps life is broken in half (Op. 17, No. 3) 1:32 17 XVI In the evening quiet hour 3:30 18 XVII I know only one thing about God (Op. 17, No. 5) 1:26 19 XVIII Lost souls! (Op. 17, No. 9) 1:51 20 XIX My endless grief (Op. 16, No. 8) 1:44 21 XX The happy laughter (Op. -

Rama Navami Birthday of Rama, the Ideal Man

folio line HOLY DAYS THAT AMERICA’S HINDUS CELEBRATE s. rajam Rama Navami Birthday of Rama, the Ideal Man organizations. They make buttermilk and a n incarnation of God, an ideal man, dutiful son and just king: lime drink called panaka, serving them to the public without charge. Some temples make these are just a few ways to describe Lord Rama, an exemplar of khoa, a sweet made from thickened milk. This Ahonor, reverence, self-control and duty. He fought battles, became festival is especially popular in Uttar Pradesh, king, married a Goddess, traveled far and befriended exotic beings who where Rama’s kingdom of Ayodhya is located. were steadfast in their loyalty and courage. Rama Navami is the cel- Is the festival observed at temples? ebration of His birthday, when Hindus honor and remember Him with Many temples hold grand celebrations on this devotional singing, dramatic performance and non-stop recitation of day, especially those with shrines for Lord His remarkable life story, the Ramayana. Rama, His wife Sita, His brother Lakshmana and His loyal friend Hanuman, Lord of Mon- keys. Panaka and garlands of the sacred When is Rama’s birth celebrated? tulsi plant are offered as families pray Rama was born on navami, the ninth for “Rama-Rajya,” a time when dharma www.dinodia.com day of the waxing moon, in the In- will once again be upheld in the world. dian month of Chaitra (late March or In South India, the day is celebrated as Panaka early April). Sometimes the festival is the marriage anniversary of Rama and Sweet Indian Limeaide observed for nine days before or after Sita. -

Ramlila of Ramnagar: an Introduction

Ramlila of Ramnagar: An Introduction Richard Schechner, Texts, Oppositions, and the Ganga River The subject of Ramlila, even Ram nagar Ramlila alone, is vast ... It touches on several texts: Ramayana of Valmiki, never uttered, but present all the same in the very fibre of Rama's story; Tulsidasa's Ramcharitmanas chanted in its entirety from before the start of the performance of Ramlila to its end. I mean that the Ramayanis spend ten days before the first lila up on the covered roof of the small 'tiring house-green room next to the square where on the twenty-ninth day of the performance Bharata Milapa will take place; there on that roof the Ramayanis chant the start of the Ramcharitmanas, from its first word till the granting of Ravana's boon : "Hear me, Lord of the World (Brahma). 1 would die at the hand of none save man or monkey." Shades of Macbeth's meeting with the witches: "For none of woman born shall harm Macbeth." Ravana, like Macbeth, is too proud. Nothing of this until the granting of Ravana's boon is heard by the Maharaja of Benares, or by the faithful daily audience called nemi-s, nor by the hundreds of sadhu-s who stream into Ramnagar for Ramlila summoned by Rama and by the Maharaja's generosity in offering sadhu-s dharamshala-s for rest and rations for the belly. The "sadhu rations" are by far the largest single expense in the Ramnagar Ramlila budget- Rs. 18,000 in 1976. Only the Ramayanis hear the start of the Ramcharitmanas- they and scholars whose job it is to "do and hear and see everything." But this, we soon discovered, is impossible: too many things happen simultaneously, scattered out across Ramnagar. -

Editors Seek the Blessings of Mahasaraswathi

OM GAM GANAPATHAYE NAMAH I MAHASARASWATHYAI NAMAH Editors seek the blessings of MahaSaraswathi Kamala Shankar (Editor-in-Chief) Laxmikant Joshi Chitra Padmanabhan Madhu Ramesh Padma Chari Arjun I Shankar Srikali Varanasi Haranath Gnana Varsha Narasimhan II Thanks to the Authors Adarsh Ravikumar Omsri Bharat Akshay Ravikumar Prerana Gundu Ashwin Mohan Priyanka Saha Anand Kanakam Pranav Raja Arvind Chari Pratap Prasad Aravind Rajagopalan Pavan Kumar Jonnalagadda Ashneel K Reddy Rohit Ramachandran Chandrashekhar Suresh Rohan Jonnalagadda Divya Lambah Samika S Kikkeri Divya Santhanam Shreesha Suresha Dr. Dharwar Achar Srinivasan Venkatachari Girish Kowligi Srinivas Pyda Gokul Kowligi Sahana Kribakaran Gopi Krishna Sruti Bharat Guruganesh Kotta Sumedh Goutam Vedanthi Harsha Koneru Srinath Nandakumar Hamsa Ramesha Sanjana Srinivas HCCC Y&E Balajyothi class S Srinivasan Kapil Gururangan Saurabh Karmarkar Karthik Gururangan Sneha Koneru Komal Sharma Sadhika Malladi Katyayini Satya Srivishnu Goutam Vedanthi Kaushik Amancherla Saransh Gupta Medha Raman Varsha Narasimhan Mahadeva Iyer Vaishnavi Jonnalagadda M L Swamy Vyleen Maheshwari Reddy Mahith Amancherla Varun Mahadevan Nikky Cherukuthota Vaishnavi Kashyap Narasimham Garudadri III Contents Forword VI Preface VIII Chairman’s Message X President’s Message XI Significance of Maha Kumbhabhishekam XII Acharya Bharadwaja 1 Acharya Kapil 3 Adi Shankara 6 Aryabhatta 9 Bhadrachala Ramadas 11 Bhaskaracharya 13 Bheeshma 15 Brahmagupta Bhillamalacarya 17 Chanakya 19 Charaka 21 Dhruva 25 Draupadi 27 Gargi -

Ramayan Ki Kathayen, Pandemic and the Hindu Way of Life and the Contribution of Hindu Women, Amongst Others

Hindu Sevika Samiti (UK) Mahila Shibir 2020 East and South Midlands Vibhag FOREWORD INSPIRING AND UNPRECEDENTED INITIATIVE In an era of mass consumerism - not only of material goods - but of information, where society continues to be led by dominant and parochial ideas, the struggle to make our stories heard, has been limited. But the tides are slowly turning and is being led by the collaborative strength of empowered Hindu women from within our community. The Covid-19 pandemic has at once forced us to cancel our core programs - which for decades had brought us together to pursue our mission to develop value-based leaders - but also allowed us the opportunity to collaborate in other, more innovative ways. It gives me immense pride that Hindu Sevika Samiti (UK) have set a new precedent for the trajectory of our work. As a follow up to the successful Mahila Shibirs in seven vibhags attended by over 500 participants, 342 Mahila sevikas came together to write 411 articles on seven different topics which will be presented in the form of seven e-books. I am very delighted to launch this collection which explores topics such as: The uniqueness of Bharat, Ramayan ki Kathayen, Pandemic and the Hindu way of life and The contribution of Hindu women, amongst others. From writing to editing, content checking to proofreading, the entire project was conducted by our Sevikas. This project has revealed hidden talents of many mahilas in writing essays and articles. We hope that these skills are further encouraged and nurtured to become good writers which our community badly lacks.