Education Managers' Understanding and Implementation of Due Process During Learner Discipline"

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Professional Development Programme 2016

NAPTOSA WESTERN CAPE PROFESSIONAL DEVELOPMENT PROGRAMME 2016 TERM ONE PROGRAMME Date Focus Group Topic Presenter Time Venue Fee Due date (to be finalised) For Bookings 1, 8, 15 Foundation Slow and reluctant readers Marlene Rousseau 15:15 – Westcott Primary Member: R230 25 January February Phase Teachers 17:15 Windsor Prep Non-member: R340 (30) Wynberg Boys’ Junior 2, 9, 16, 23 Foundation Creative Writing Judi Kurgan 15:15 – Erica Primary Member: R290 26 January February phase teachers 17:15 Blouberg Ridge Non-member: R400 (30) Primary Montevideo Primary 3, 10, 17, All Teachers Blended learning Jeremy Gibbon 15:15 – Portavue Primary Member: R300 27 January 24 February 17:15 Rondebosch East PrimaryNon- member: R410 (30) 2 March Tamboerskloof Primary 3, 10, 24 Grade 8 – 12 Creative Writing Charmaine Kendal 15:15 – CTLI Member: R300 27 January February English teachers 17:15 Rustenburg Girls’ Non-member: R410 (30) 2, 9 March High Alexander Sinton High 4, 11, 18, 25 All teachers Discipline for Peace Karin Quail 15:15 – Star of the Sea Member: R320 28 January February 17:15 Primary Non-member: R430 (40) 3 March Muizenberg Junior Bergvliet Primary Date Focus Group Topic Presenter Time Venue Fee Due date for (to be finalised) Bookings 4, 11, 18, 25 All teachers Conversational IsiXhosa Linda Pauw 15:15 – Camps Bay High Member: R400 28 January February; 3, Level 1 16:45 Norman Non-member: R510 (30) 10, 17 March Henshilwood High Muizenberg High 8, 15 All teachers Mimio / Smartboard Charmaine Roynon 15:15 – Eversdal Primary Member: R200 1 February -

13-17 July 2015 Name of School Surname Name Total

13-17 July 2015 Name of School Surname Name Total HS Porterville Breytenbach Elmarie Steynville Sek Carstens Liza-Mari Vooruitsig PS De Bruyn Johan HS Dirkie Uys De Vreye Leney HS Swartland Du Preez I Vooruitsig PS Engelbrecht Richard Stawelklip PS Faro Mathilda Willemsvallei PS Fortuin PM HS Swartland Gerber R HS Aurora Horne Susarah Schoon-spruit Sek Karstens Tashline Riebeek-Wes PS Mentoor Maurese Riebeek-Wes PS Mentoor Nicola Riebeek-Wes PS Nel Karen Schoon-spruit Sek Rinquest Jade Stawelklip PS Schaffers Brandon Wesbank Sek Strydom Steel Laurie Hugo PS Swart John Laurie Hugo PS Swart John Gary Wesbank Sek Van der Merwe Eunice Schoon-spruit Sek Van der Merwe Anneke Schoon-spruit Sek Van der Merwe Brynmor Steynville Sek Van Rooyen Rashonia HS Swartland Visser GJ Wesbank Sek Willemse Sharon Ashton PC (CW) Gqamana Luvuyo Ashton PC (CW) Magida Noxolo Van Cutsem (CW) Zondo Siphumuzile Van Cutsem (CW) Tose Vuyani, Masakheke HS (CW) Harmse Shaun Masakheke HS (CW) Basvi Stevin Paul Roos Gim Canaris Christine Vusisiswe Secondary Kula Phumla Vusisiswe Secondary Mthenjana Patrick Iingcinga Zethu Yame Mninawe Makapula Noji Nolubabalo Makupula Den Merg Diza Makupula Magwaca Nomfuneko Desmond Tutu Nqoyo Nompume-lelo Desmond Tutu Mbulawa Bukelwa Desmond Tutu Siduma Mandla Kayamandi HS Ngcwebo Ntombi Kayamandi HS Mpokeli Zanomzi Kayamandi HS Phinda Makapela Langeberg Williams Esther Langeberg Eksteen Henry Langeberg Munnik Melvyn De Kruine Sek April Yolandi Ilingellethu HS Mhambi Unathi Ilingellethu HS Mangcengeza Wandile Diazville HS Kaba Nomveliso -

Directory of Organisations and Resources for People with Disabilities in South Africa

DISABILITY ALL SORTS A DIRECTORY OF ORGANISATIONS AND RESOURCES FOR PEOPLE WITH DISABILITIES IN SOUTH AFRICA University of South Africa CONTENTS FOREWORD ADVOCACY — ALL DISABILITIES ADVOCACY — DISABILITY-SPECIFIC ACCOMMODATION (SUGGESTIONS FOR WORK AND EDUCATION) AIRLINES THAT ACCOMMODATE WHEELCHAIRS ARTS ASSISTANCE AND THERAPY DOGS ASSISTIVE DEVICES FOR HIRE ASSISTIVE DEVICES FOR PURCHASE ASSISTIVE DEVICES — MAIL ORDER ASSISTIVE DEVICES — REPAIRS ASSISTIVE DEVICES — RESOURCE AND INFORMATION CENTRE BACK SUPPORT BOOKS, DISABILITY GUIDES AND INFORMATION RESOURCES BRAILLE AND AUDIO PRODUCTION BREATHING SUPPORT BUILDING OF RAMPS BURSARIES CAREGIVERS AND NURSES CAREGIVERS AND NURSES — EASTERN CAPE CAREGIVERS AND NURSES — FREE STATE CAREGIVERS AND NURSES — GAUTENG CAREGIVERS AND NURSES — KWAZULU-NATAL CAREGIVERS AND NURSES — LIMPOPO CAREGIVERS AND NURSES — MPUMALANGA CAREGIVERS AND NURSES — NORTHERN CAPE CAREGIVERS AND NURSES — NORTH WEST CAREGIVERS AND NURSES — WESTERN CAPE CHARITY/GIFT SHOPS COMMUNITY SERVICE ORGANISATIONS COMPENSATION FOR WORKPLACE INJURIES COMPLEMENTARY THERAPIES CONVERSION OF VEHICLES COUNSELLING CRÈCHES DAY CARE CENTRES — EASTERN CAPE DAY CARE CENTRES — FREE STATE 1 DAY CARE CENTRES — GAUTENG DAY CARE CENTRES — KWAZULU-NATAL DAY CARE CENTRES — LIMPOPO DAY CARE CENTRES — MPUMALANGA DAY CARE CENTRES — WESTERN CAPE DISABILITY EQUITY CONSULTANTS DISABILITY MAGAZINES AND NEWSLETTERS DISABILITY MANAGEMENT DISABILITY SENSITISATION PROJECTS DISABILITY STUDIES DRIVING SCHOOLS E-LEARNING END-OF-LIFE DETERMINATION ENTREPRENEURIAL -

Submission on the Feasibility Model for Social Housing on the Tafelberg Site

TAFELBERG SUBMISSION ON THE FEASIBILITY MODEL FOR SOCIAL HOUSING ON THE TAFELBERG SITE March 2017 TAFELBERG SUBMISSION ON THE FEASIBILITY MODEL FOR SOCIAL HOUSING ON THE TAFELBERG SITE March 2017 Written by Julian Sendin, Martha Sithole, Sarita Pillay, and Shaun Russell Architectural Drawings by Azraa Rawoot, Ruvimbo Moyo and Loyiso Qaqane Layout by Chad Rossouw and Azraa Rawoot Massing Model by Azraa Rawoot and Julian Sendin Financial Model by Jacus Pienaar and Julian Sendin Edited by Hopolang Selebalo, Jared Rossouw and Rich Conyngham Other comments and contributions by Malcolm Mc- Carthy, Jodi Allemeir, Lungelo Nkosi and many other professionals who requested anonymity CONTENTS ACRONYMS & ABBREVIATIONS 5 INTRODUCTION: WHEN WILL SEGREGATION END? 6 PART ONE 7 Segregation & Affordable Housing 10 THE affordable housing crisis 17 LAND Use TracK Record IN cape town 21 Housing TracK Record IN Cape TOwn 28 Social Housing TracK Record IN Cape Town 34 Obligations: THE Constitution, Law AND Policy 39 SEA Point: THE NEED For Affordable Housing 47 Tafelberg: unjust AND unlawful sale 56 Endnotes 67 PART TWO 77 Comment on Model 83 Endnotes 93 PART THREE 97 Development concept AND principles 99 site analysis 100 Development Concept 104 French School precedent (Tafelberg Primary) 105 Base Assumptions 107 Scenario one: Traditional four-storey social housing typology 108 Scenario two: MID-rise social housing typology 110 ENDnotes 116 ACRONYMS & ABBREVIATIONS AFR Asset Finance Reserve PERO Provincial Economic Review and Outlook BEPP Built Environment -

Western Cape Provincial List 2019

Basic Education Support — 2019 Western Cape Province Page 1 of 2 Updated: 18/01/2019 BASIC REF NUMBER DEPENDENT NAME DEPENDENT SURNAME SCHOOL NAME PROVINCE APPROVAL STATUS AS PER COMMITTEE BE - CONT 3476 QENIEVIA HYGER ABRAHAMS BASTIAANSE SECONDARY SCHOOL WC BE - CONT 3660 RONIECHIA ABRAHAMS BASTIAANSE SECONDARY SCHOOL WC BE - CONT 1131 JUAN MATHEW ALEXANDER ZWAANSWYK HIGH SCHOOL WC APPROVED BE - CONT 0045 AKEESHEA ALFESTUS RUSTHOF PRIMARY WC APPROVED BE - CONT 0008 ABIGAIL WILLEHE APRIL HILLCREST SECONDARY SCHOOL WC APPROVED BE - CONT 1115 JOSE AYFORD AURIAL COLLEGE WC BE - CONT 2236 MARCHELL BAADJIES CERES SECONDARY SCHOOL WC APPROVED BE - CONT 4906 ZENA BAATJIES HERMANUS HIGH SCHOOL WC BE - CONT 4924 ZHARR BAATJIES HERMANUS PRE PRIMARY SCHOOL WC BE - CONT 0118 AMYOLI BALENI MARY HELP OF CHRISTIANS PRIMARY WC BE - CONT 0129 ANDA BAM BLOUBERG RIDGE PRIMARY SCHOOL WC BE - CONT 2038 LUNATHI BASSO SANS SOUCI GIRL HIRLS SCHOOL WC APPROVED BE - CONT 0306 AYABULELA ONKE BATYI GOOD HOPE SEMINARY HIGH SCHOOL WC BE - CONT 2413 MIHLALI BATYI ST MARY'S PRIMARY SCHOOL WC BE - CONT 0767 ED-NICK BELL HOERSKOOL LADISMITH WC APPROVED BE - CONT 0146 ANDRE JEAN BENN SAREPTA SECONDARY SCHOOL WC APPROVED BE - CONT 3835 SHIMONE ANASTASIA BLAAUW VREDENDAL SECONDARY SCHOOL WC BE - CONT 0938 HADLEY MATTHEW BOEZAK PAROW HIGH SCHOOL WC BE - CONT 0664 CLAUDE ILGAR BOKS LUTZVILLE HIGH SCHOOL WC BE - CONT 4982 HERMAN BOKS HOERSKOOL VANRHYNSDORP WC BE - CONT 4958 ZOE ZULEIKA BOOI BELHAR HIGH SCHOOL WC BE - CONT 1646 KYLE BOONZAAIER MUIZENBERG JUNIOR SCHOOL WC APPROVED -

Judgment: 31 August 2020

IN THE HIGH COURT OF SOUTH AFRICA WESTERN CAPE DIVISION, CAPE TOWN REPORTABLE CASE NO: 7908/2017 In the matter between: THOZAMA ANGELA ADONISI First Applicant PHUMZA NTUTELA Second Applicant SHARONE DANIELS Third Applicant SELINA LA HANE Fourth Applicant RECLAIM THE CITY Fifth Applicant TRUSTEES OF THE NDIFUNA UKWAZI TRUST Sixth Applicant And MINISTER FOR TRANSPORT AND PUBLIC WORKS: WESTERN CAPE First Respondent PREMIER OF THE WESTERN CAPE PROVINCE Second Respondent THE PHYLLIS JOWELL JEWISH DAY SCHOOL (NPC) Third Respondent CITY OF CAPE TOWN Fourth Respondent MINISTER OF HUMAN SETTLEMENTS Fifth Respondent THE PROVINCIAL GOVERNMENT OF THE WESTERN CAPE Sixth Respondent THE MINISTER OF PUBLIC WORKS Seventh Respondent 2 THE MINISTER OF HUMAN SETTLEMENTS: WESTERN CAPE Eighth Respondent SOCIAL HOUSING REGULATORY AUTHORITY Ninth Respondent MINISTER OF RURAL DEVELOPMENT & LAND REFORM Tenth Respondent MINISTER OF FINANCE Eleventh Respondent GARY FISHER Twelfth Respondent AND IN CASE NO.12327/2017 In the matter between: MINISTER OF HUMAN SETTLEMENTS First Applicant NATIONAL DEPARTMENT OF HUMAN SETTLEMENTS Second Applicant SOCIAL HOUSING REGULATORY AUTHORITY Third Applicant and PREMIER OF THE WESTERN CAPE PROVINCE First Respondent MEC FOR TRANSPORT AND PUBLIC WORKS: WESTERN CAPE PROVINCE Second Respondent MEC FOR HUMAN SETTLEMENTS: WESTERN CAPE PROVINCE Third Respondent CITY OF CAPE TOWN Fourth Respondent THE PHYLLIS JOWELL JEWISH DAY SCHOOL (NPC) Fifth Respondent TRUSTEES OF THE NDIFUNA UKWAZI TRUST Sixth Respondent 3 Coram: P.A.L. Gamble and M.I. Samela, JJ. Date of Hearing: 25, 26, 27, 28 & 29 November 2019. Date of Judgment: 31 August 2020. JUDGMENT DELIVERED ON 31 AUGUST 2020 ____________________________________________________________________ GAMBLE, J: INTRODUCTION 1. -

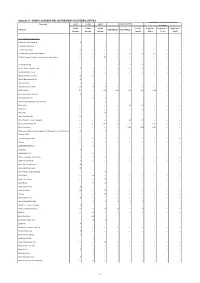

Ann 11 Grants Subs and Contr to Ext Orgs 1415.Xlsx

Annexure 11 - GRANTS, SUBSIDIES AND CONTRIBUTIONS TO EXTERNAL ENTITIES 2014/15 Medium Term Revenue & Expenditure Description 2010/11 2011/12 2012/13 Current Year 2013/14 Framework Audited Audited Audited Full Year Budget Year Budget Year +1 Budget Year +2 R thousand Original Budget Adjusted Budget Outcome Outcome Outcome Forecast 2014/15 2015/16 2016/17 Cash Transfers to Organisations 1st Bellville South Scout Group 10 – – – – – – – – 1st Bothasig Scout Group – – 5 – – – – – – 1st Ikwezi Scout Group 15 – – – – – – – – 2013 Maboneng Guguletu Arts Experience – – – – 50 50 150 – – 6th World Congress: Paediatric Cardiology and Cardiac Surgery – – 750 – – – – – – 7570 Youth in Action – – – 7 7 7 – – – Abafazi iTemba - Women of Hope 10 – – – – – – – – Abangane Religious Group – 4 – – – – – – – Abaphumeleli Home of Safety 38 20 – – – – – – – Abatsha Environmental Group 96 – – – – – – – – Abba HIV Project 5 5 5 – – – – – – Abigail Women's Movement 72 18 23 – – – – – – ABSA Cape Epic 500 – 1 278 1 350 1 350 1 350 1 445 – – Actor's Voice Davedu-tainment 19 – – – – – – – – ACVV Bothasig Creche – 10 8 – – – – – – ACVV Old Age Home: ACVV Huis Jan Swart – – 15 – – – – – – Africa Centre – – – – 450 450 – – – Africa Tales – 3 – – – – – – – Africa Unite – – 37 – – – – – – African Centre for Cities 350 – – – – – – – – African Creative Economy Conference – – – – 600 600 – – – African Fashion International – – 1 200 – – – 1 300 – – African Travel Week – – – – 2 750 2 750 2 750 – – Afrikaanse Christelike Vroue Vereniging (ACVV De Grendel Creche ACVV Crèche, -

A Scholarly Inquiry Into Disciplinary Practices in Educational Institutions Izak J

Volume 2 Volume NWU Education and Human Rights in Diversity Series in Diversity and Human Rights NWU Education educational institutions educational disciplinary practices in A scholarly inquiry into inquiry into A scholarly Connie B. Zulu, Izak J. Oosthuizen & Charl C. Wolhuter Connie B. Zulu, Izak J. Oosthuizen & Charl C. Wolhuter Edited by: Connie B. Zulu, A scholarly inquiry into disciplinary practices in educational institutions Izak J. Oosthuizen & Charl C. Wolhuter (eds.) NWU Education and Human Rights in Diversity Series Volume 2 A scholarly inquiry into disciplinary practices in educational institutions Published by AOSIS (Pty) Ltd, 15 Oxford Street, Durbanville 7550, Cape Town, South Africa Postnet Suite #110, Private Bag X19, Durbanville 7551, South Africa Tel: +27 21 975 2602 Fax: +27 21 975 4635 Email: [email protected] Website: https://www.aosis.co.za Copyright © Connie B. Zulu, Izak J. Oosthuizen & Charl C. Wolhuter (eds.). Licensee: AOSIS (Pty) Ltd. The moral right of the author has been asserted. Cover image: Original design created with the use of two images.The book https://pixabay. com/fr/photos/livre-lecture-litt%C3%A9rature-pages-1549589/ The mountains https:// pixabay.com/pt/photos/montanhas-c%C3%A9u-azul-natureza-4312789. Published in 2019 Impression: 1 ISBN: 978-1-928523-13-0 (print) ISBN: 978-1-928523-14-7 (epub) ISBN: 978-1-928523-15-4 (pdf) DOI: https://doi.org/10.4102/aosis.2019.BK157 How to cite this work: Zulu, C.B., Oosthuizen, I.J. & Wolhuter, C.C. (eds.), 2019, ‘A scholarly inquiry into disciplinary practices in educational institutions’, in NWU Education and Human Rights in Diversity Series Volume 2, pp. -

Professional Development Programme

PROFESSIONAL DEVELOPMENT PROGRAMME 2017 Term One Date Focus Group Topic Presenter Time Venue Fee Due date (to be finalised) For Bookings 14 January New Teachers & Course: School Readiness Alex Pinnock & 08:30 – Belgravia High Member: R240 9 December Teachers with 1 or for Teachers Shandre Otto 12:30 Bergvliet High Non-member: R480 2016 2 years’ experience Bergvliet Primary (40) 19, 26 January; 2, 9 15:15 – February 17:15 6, 13, 20, 27 Grade 8 -12 English Creative Writing Charmaine Kendal 15:15 – Jan Kriel School Member: R260 30 January February; 6 Teachers 17:15 St Joseph’s Marist Non-member: R530 (30) March Brothers The Settlers High 8 February Grade 10 – 12 Financial Maths Debbie Marucchi 15:15 – Point High (Mossel Member: R100 1 February Maths Teachers 17:45 Bay) Non-member: R220 (50) Thembalethu High (George) Wittedrift High (Plettenberg Bay) (Southern Cape Event) 9 February Grade 12 Calculus Debbie Marucchi 15:15 – York High (George) Member: R100 2 February Maths Teachers 17:45 Albertinia High Non-member: R220 (50) (Albertinia) Aurial College (Oudshoorn) (Southern Cape Event) 11, 25 HOD’s & Aspiring Leading and Managing a Schools 09:00 – UCT Member: R470 3 February February; 11, HOD’s Curriculum delivery Team Development Unit, 12:30 Non-member: R600 (30) 25 March UCT 13, 20, 27 All Primary School Social Emotional Learning Linda Bruce 15:15 – CTLI Member: R450 6 February February Teachers 17:15 Ysterplaat Primary Non-member: R570 (50) Ysterplaat Junior Primary 15, 22 All Teachers Temperament for Teachers Karen Quail 15:15 – Tafelberg -

Drama Poems Speech Prose Reading Ca to Cz

DRAMA POEMS SPEECH PROSE READING CA TO CZ MAANDAG 21 AUGUSTUS REKORDKLERK: Bruwer Hayman PAROW-NOORD LAERSKOOL [SAAL] CA Spreekkore 12 – Sonja Engelbrecht CA 1 Graad R[6] TYD/TIME Durbanville Voorbereidingskool (bq) 1 15:00 Durbanville Preparatory School (sh) 1 15:00 CA 2 Graad 1 Fanie Theron Primary School (bz) 1 15:00 Saffier Primary School (dn) 1 15:00 CA 4 Graad 3 Durbanville Voorbereidingskool (bq) 1 15:00 Fanie Theron Primary School (bz) 1 15:00 CA 7 Graad 6[4] Alpha Laerskool (ae) 1 16:20 Parkdene Primêre Skool (st) 1 16:20 CA 8 Graad 7 Alpha Laerskool (ae) 1 16:20 Cavalleria Primary School (aw) 1 16:20 DINSDAG 22 AUGUSTUS REKORDKLERK: Bruwer Hayman PAROW-NOORD LAERSKOOL [SAAL] CB Gedramatiseerde Spreekkore – Sonja Engelbrecht CB 15 Graad R-3[3] TYD/TIME Kammalielie Kammalollie (Veronica Geldenhuys) (ld) 1 15:00 CB 5 Graad 4 Gene Louw Primary School (cb) 1 15:00 CB 7 Graad 6 Gene Louw Primary School (cb) 1 15:00 CB 8 Graad 7 [5] Aristea Primary School (af) 1 15:50 Bellpark Primary School (ak) 1 15:50 Durbanville Primary School (bp) 1 15:50 Gene Louw Primary School (cb) 1 15:50 CB 12 Graad 11 Brackenfell High School (gf) 1 15:50 WEDNESDAY 23 AUGUST RECORD CLERK: Bruwer Hayman PAROW NORTH PRIMARY SCHOOL [HALL] CC Speech Choir 14 – Zelda Langeveldt CC 1 Grade R [8] TIME/TYD Woodbridge Primary (eq) 1 15:00 CC 15 Grade R-3 Combined Section Woodbridge Primary (eq) 1 15:0 Melkbosstrand Private School (hg) 1 15:00 CC 2 Grade 1 Panorama Primary School (da) 1 15:00 CC 4 Grade 3 Bosmansdam Primary School (ar) 1 15:0 Brackenfell Primary School -

DEPARTMENT of EDUCATION VOTE 05 2011/12 ANNUAL REPORT 1. General Information Vision, Mission and Values

DEPARTMENT OF EDUCATION VOTE 05 2011/12 ANNUAL REPORT 1. General Information Vision, mission and values ............................................................................................................. 1 Organisational structure ................................................................................................................. 1 Legislative mandate ....................................................................................................................... 2 Entities reporting to the Minister ..................................................................................................... 2 Minister’s statement ....................................................................................................................... 2 Accounting officer’s overview ......................................................................................................... 4 2. Information on predetermined objectives 2.1 Overall performance ....................................................................................................................... 6 2.1.1 Voted funds .................................................................................................................................... 6 2.1.2 Aim of vote ..................................................................................................................................... 6 2.1.3 Strategic Outcome Oriented Goals ................................................................................................. 6 2.1.4 Overview -

Procurement Disclosure Report April-July 2020.Pdf

PROCUREMENT IN THE WESTERN CAPE | 01/4/2020 – 31/07/2020 | ISSUE 2: 31 AUGUST 2020 PROCUREMENT DISCLOSURE REPORT 1 Introduction REFLECTIONS ON PPE PURCHASING Since the declaration of the National Disaster, the In line with the requirements of section 217 of the Western Cape Government has spent R 683.78 South African Constitution and the Western Cape million on Personal Protective Equipment (PPE). This equipment is essential to ensuring that basic Government’s (Western Cape Government), services continued to be provided whilst continued commitment to clean governance and protecting frontline and essential staff when performing their functions. transparency in public procurement, the Provincial Treasury is pleased to publish the second edition of Procurement in the Province has been managed from a centre-led approach and not a centralised the Procurement Disclosure Report for Western Cape. approach. This report details all COVID-19 expenditure in the • All departments procure their own PPE requirements through their own supply chains in Western Cape from 1 April 2020 until 31 July 2020 keeping with prescribed provincial and and goes further than previous edition that dealt national requirements; only with PPE. • Provincial Treasury has established databases of suppliers for cloth masks and other PPE that Procurement Disclosure Reports are published on the enable: (i) standardised, uniform have been approved by the Departments of Health were Provincial Treasury website. The next report will be utilised; (ii) pricing for each item, lead times for available on 30 September 2020. delivery and quantities that suppliers could deliver; and (iii) this could be compared to benchmark prices that are issued and adjusted Background by the National Treasury.