Clarett's Motion for Summary Judgment

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Cheap Jerseys on Sale Including the High Quality Cheap/Wholesale Nike

Cheap jerseys on sale including the high quality Cheap/Wholesale Nike NFL Jerseys,NHL Jerseys,MLB Jerseys,NBA Jerseys,NFL Jerseys,NCAA Jerseys,Custom Jerseys,Soccer Jerseys,Sports Caps offer low price with free shipping!Close this window For quite possibly the most captivating daily read, Make Yahoo,create a hockey jersey! your Homepage Wed Aug eleven 04:37pm EDT Training Camp Confidential: Forsett finally gets a multi function real chance By Doug Farrar Through the Seattle Seahawks' 2010 training camp,customized nba jersey,soccer jersey shop, we'll be the case after having been running back Justin Forsett(notes) as the player is found in to educate yourself regarding take that in the next motivation from offensive cog for more information regarding feature back everywhere over the his acquire NFL season. In this second installment all your family can read Part one in the following paragraphs Forsett recalls his days at Cal,michigan state football jersey, and his current running backs coach outlines so how do you 2010 do nothing more than might be on the lookout for a ach and every competitive running back rotation."You can do nothing more than make sure they know on the basis of his game play that he's some form of having to do with the toughest guys everywhere over the the line of business He has a multi functional zit everywhere in the his shoulder brace because every man and woman said that they was too small. But, I mean -- if all your family do nothing more than churn throughout the his game eternal both to and from last year, he's going to be the toughest guy you can purchase He's going for more information regarding take a multi functional hit. -

1-1-17 at Los Angeles.Indd

WEEK 17 GAME RELEASE #AZvsLA Mark Dalton - Vice President, Media Relations Chris Melvin - Director, Media Relations Mike Helm - Manag er, Media Relations Matt Storey - Media Relations Coordinator Morgan Tholen - Media Relations Assistant ARIZONA CARDINALS (6-8-1) VS. LOS ANGELES RAMS (4-11) L.A. Memorial Coliseum | Jan. 1, 2017 | 2:25 PM THIS WEEK’S GAME ARIZONA CARDINALS - 2016 SCHEDULE The Cardinals conclude the 2016 season this week with a trip to Los Ange- Regular Season les to face the Rams at the LA Memorial Coliseum. It will be the Cardinals Date Opponent Loca on AZ Time fi rst road game against the Los Angeles Rams since 1994, when they met in Sep. 11 NEW ENGLAND+ Univ. of Phoenix Stadium L, 21-23 Anaheim in the season opener. Sep. 18 TAMPA BAY Univ. of Phoenix Stadium W, 40-7 Last week, Arizona defeated the Seahawks 34-31 at CenturyLink Field to im- Sep. 25 @ Buff alo New Era Field L, 18-33 prove its record to 6-8-1. The victory marked the Cardinals second straight Oct. 2 LOS ANGELES Univ. of Phoenix Stadium L, 13-17 win at Sea le and third in the last four years. QB Carson Palmer improved to 3-0 as Arizona’s star ng QB in Sea le. Oct. 6 @ San Francisco# Levi’s Stadium W, 33-21 Oct. 17 NY JETS^ Univ. of Phoenix Stadium W, 28-3 The Cardinals jumped out to a 14-0 lead a er Palmer connected with J.J. Oct. 23 SEATTLE+ Univ. of Phoenix Stadium T, 6-6 Nelson on an 80-yard TD pass in the second quarter and they held a 14-3 lead at the half. -

Print Profile

Kurt Warner finished the 1999-2000 NFL season with a 414-yard performance in Super Bowl XXXIV, shattering Joe Montana's Super Bowl-record 357 passing yards. Kurt Warner Not only did that performance lead the St. Louis Rams past the Tennessee Titans, it earned him Super Bowl MVP honors as well. During the regular 1999-2000 season, Kurt amassed 4,353 yards, 41 touchdowns, and a 109.1 passer rating - quite a feat Speech Topics for a guy who was bagging groceries a few years ago. Along with success came the inevitable media coverage. Cameras and microphones were in Kurt's face more than ever before. But what do you say with all the new attention? Some Youth professional athletes use the publicity for self glory, but Kurt Warner has a Sports different topic on his mind. It's the message of Jesus Christ. Kurt is a Christian who Motivation jumps at the chance to give God the credit for his ability to play football. He was Life Balance proclaiming the Good News in his first words after victory in the Super Bowl and Inspiration he continues to this day, shouting, Thank you, Jesus! It's a refreshing thing to hear a pro player speak the name of Christ instead of his own. Celebrity "Looking at the big picture, I know my role in this is to help share my faith, and to share my relationship with the Lord in this capacity. The funny thing is my wife, when I tell her about some interviews that I've done, she's always asking me, 'Don't talk about the Lord in every answer that you give.' I come back and tell her, 'Hey, they try to cut out as much of those (religious comments) as they can. -

The Role of Preferences, Cognitive Biases, and Heuristics Among Professional Athletes Michael A

Brooklyn Law Review Volume 71 | Issue 4 Article 1 2006 It's Not About the Money: The Role of Preferences, Cognitive Biases, and Heuristics Among Professional Athletes Michael A. McCann Follow this and additional works at: https://brooklynworks.brooklaw.edu/blr Recommended Citation Michael A. McCann, It's Not About the Money: The Role of Preferences, Cognitive Biases, and Heuristics Among Professional Athletes, 71 Brook. L. Rev. (2006). Available at: https://brooklynworks.brooklaw.edu/blr/vol71/iss4/1 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Law Journals at BrooklynWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in Brooklyn Law Review by an authorized editor of BrooklynWorks. ARTICLES It’s Not About the Money: THE ROLE OF PREFERENCES, COGNITIVE BIASES, AND HEURISTICS AMONG PROFESSIONAL ATHLETES Michael A. McCann† I. INTRODUCTION Professional athletes are often regarded as selfish, greedy, and out-of-touch with regular people. They hire agents who are vilified for negotiating employment contracts that occasionally yield compensation in excess of national gross domestic products.1 Professional athletes are thus commonly assumed to most value economic remuneration, rather than the “love of the game” or some other intangible, romanticized inclination. Lending credibility to this intuition is the rational actor model; a law and economic precept which presupposes that when individuals are presented with a set of choices, they rationally weigh costs and benefits, and select the course of † Assistant Professor of Law, Mississippi College School of Law; LL.M., Harvard Law School; J.D., University of Virginia School of Law; B.A., Georgetown University. Prior to becoming a law professor, the author was a Visiting Scholar/Researcher at Harvard Law School and a member of the legal team for former Ohio State football player Maurice Clarett in his lawsuit against the National Football League and its age limit (Clarett v. -

2 Den at Chi 08 16 2003 Fli

Denver Broncos vs Chicago Bears Saturday, August 16, 2003 at Memorial Stadium BEARS BEARS OFFENSE BEARS DEFENSE BRONCOS No Name Pos WR 80 D.White 83 D.Terrell 87 J.Elliott LE 93 P.Daniels 99 J.Tafoya 63 C.Demaree No Name Pos 10 Stewart,Kordell QB WR 16 E.Shepherd 18 J.Gage LT 92 T.Washington 70 A.Boone 71 I.Scott 1 Elam,Jason K 11 Barnard,Brooks P 11 Beuerlein,Steve QB 12 Chandler,Chris QB LT 69 M.Gandy 60 T.Metcalf 63 P.Lougheed RT 98 B.Robinson 94 K.Traylor 72 E.Grant 12 Adams,Charlie WR 15 Forde,Andre WR LG 64 R.Tucker 73 S.Grice 62 T.Vincent DT 73 T.LaFavor 67 T.Benford 13 Madise,Adrian WR 16 Shepherd,Edell WR 14 Jackson,Nate WR 17 Sauter,Cory QB C 57 O.Kreutz 74 B.Robertson 67 J.Warner RE 96 A.Brown 97 M.Haynes 76 B.Setzer 15 Rice,Frank WR 18 Gage,Justin WR RG 58 C.Villarrial 67 J.Warner 68 B.Anderson WLB 53 W.Holdman 55 M.Caldwell 59 J.Odom 16 Plummer,Jake QB 19 Thurmon,Elijah WR 17 Jackson,Jarious QB 2 Edinger,Paul K RG 76 J.Grzeskowiak 71 J.Soriano MLB 54 B.Urlacher 52 B.Howard 62 J.Schumacher 2 Rolovich,Nick QB 20 Williams,Roosevelt CB RT 78 A.Gibson 79 S.Edwards 75 M.Colombo SLB 90 B.Knight 91 L.Briggs 55 M.Caldwell 20 Jackson,Marlion RB 21 McQuarters,R.W. CB 21 Kelly,Ben CB 22 Hicks,Maurice RB TE 88 D.Clark 89 D.Lyman 85 J.Gilmore LCB 21 R.McQuarters 20 R.Williams 46 J.Goss 22 Griffin,Quentin RB 23 Azumah,Jerry CB TE 46 B.Fletcher 49 M.Afariogun 82 J.Davis LCB 26 T.McMillon 24 E.Joyce 23 Middlebrooks,Willie CB 24 Joyce,Eric CB 24 O'Neal,Deltha CB 25 Gray,Bobby SS TE 48 R.Johnson RCB 23 J.Azumah 33 C.Tillman 39 T.Gaines 25 Ferguson,Nick -

How Mike Williams & Maurice Clarett Lost Their Chance

DePaul Journal of Sports Law Volume 3 Issue 1 Summer 2005 Article 2 Losing Collegiate Eligibility: How Mike Williams & Maurice Clarett Lost their Chance to Perform on College Athletics' Biggest Stage Michael R. Lombardo Follow this and additional works at: https://via.library.depaul.edu/jslcp Recommended Citation Michael R. Lombardo, Losing Collegiate Eligibility: How Mike Williams & Maurice Clarett Lost their Chance to Perform on College Athletics' Biggest Stage, 3 DePaul J. Sports L. & Contemp. Probs. 19 (2005) Available at: https://via.library.depaul.edu/jslcp/vol3/iss1/2 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the College of Law at Via Sapientiae. It has been accepted for inclusion in DePaul Journal of Sports Law by an authorized editor of Via Sapientiae. For more information, please contact [email protected]. LOSING COLLEGIATE ELIGIBILITY: HOW MIKE WILLIAMS & MAURICE CLARETT LOST THEIR CHANCE TO PERFORM ON COLLEGE ATHLETICS' BIGGEST STAGE Michael R. Lombardo* INTRODUCTION In the fall of 2002 Maurice Clarett was on top of the world. His team, the Ohio State Buckeyes, had just completed a remarkable season in which they dominated college football. They finished the season a perfect 14-0, winning the Big Ten Conference Championship and the National Championship. In the Fiesta Bowl, the Buckeyes were matched up against the undefeated Miami Hurricanes, who had not lost a game since September of 2000.' The Buckeyes were twelve-point underdogs at kickoff and the experts did not give them much of a chance at winning.2 However, behind the remarkable effort of their star freshman tailback, Ohio State shocked the Miami Hurricanes and the college football world with a 31-24 victory. -

Denver Broncos Vs Seattle Seahawks Sunday, November 17, 2002

Denver Broncos vs Seattle Seahawks Sunday, November 17, 2002 at Seahawks Stadium SEAHAWKS SEAHAWKS OFFENSE SEAHAWKS DEFENSE BRONCOS No Name Pos WR 81 K.Robinson 88 J.Williams 85 A.Bannister LDE 92 L.King 91 A.Palepoi No Name Pos 10 Feagles,Jeff P LT 71 W.Jones 68 D.Norman LDT 90 C.Eaton 98 C.Woodard 1 Elam,Jason K 17 Kelly,Jeff QB 11 Beuerlein,Steve QB 20 Morris,Maurice RB LG 62 C.Gray RDT 93 J.Randle 99 R.Bernard 14 Griese,Brian QB 21 Lucas,Ken CB C 61 R.Tobeck 68 D.Norman RDE 78 A.Cochran 95 J.Hilliard 17 Jackson,Jarious QB 24 Springs,Shawn CB 21 Coleman,KaRon RB 25 Tongue,Reggie S RG 69 F.Wedderburn OLB 55 M.Bell 54 D.Lewis 51 A.Simmons 22 Gary,Olandis RB 27 Williams,Willie CB RT 77 F.Womack 70 J.Wunsch 74 M.Hill MLB 57 O.Huff 53 K.Miller 58 I.Kacyvenski 23 Middlebrooks,Willie S 28 Blackmon,Harold S 24 O'Neal,Deltha CB 29 Fuller,Curtis S TE 89 I.Mili 86 J.Stevens 83 R.Hannam OLB 59 T.Terry 56 T.Killens 25 Walker,Denard CB 3 George,Jeff QB WR 88 J.Williams 84 B.Engram 87 K.Kasper LCB 24 S.Springs 27 W.Williams 42 K.Richard 26 Portis,Clinton RB 31 Robertson,Marcus S 28 Kennedy,Kenoy S 33 Evans,Doug CB 82 D.Jackson RCB 21 K.Lucas 33 D.Evans 31 Herndon,Kelly CB 34 Bierria,Terreal S QB 8 M.Hasselbeck 3 J.George 17 J.Kelly SS 25 R.Tongue 28 H.Blackmon 33 Spencer,Jimmy CB 37 Alexander,Shaun RB 34 Droughns,Reuben RB 38 Strong,Mack FB FB 38 M.Strong 44 H.Evans FS 31 M.Robertson 29 C.Fuller 34 T.Bierria 35 Walls,Lenny CB 42 Richard,Kris CB RB 37 S.Alexander 20 M.Morris 37 Poole,Tyrone CB 44 Evans,Heath FB 38 Anderson,Mike RB 51 Simmons,Anthony LB 4 Knorr,Micah P/K 52 Darche,J.P. -

Antoine Cason Football Camp Learn Football from the Best!

Learn Football from the Best! Antoine Cason Football Camp Learn individual and team techniques on both offense and defense from an outstanding coaching staff and members of the San Diego Chargers! Antoine Cason Overnight Football Camp July 6 – 9, 2011 San Diego State University Chris Kluwe Kicking & Punting Camp July 6, 2011 San Diego State University Antoine Cason Day Football Camp July 12 – 13, 2011 John Glenn High School, Norwalk, CA FOR ALL FOOTBALL PLAYERS AGES 7–18! 28TH BIG YEAR FOR SPORTS INTERNATIONAL CAMPS! Join an Outstanding Coaching Staff, Antoine Cason and members of the San Diego Chargers! The San Diego Chargers players who coach at Antoine’s camp teach the same offensive and defensive techniques they are taught by the San Diego Chargers’ coaching staff! You will receive daily instruction, lectures and demonstrations by Antoine Cason and/or members of the San Diego Chargers! Some of the Chargers that have attended the camp include: Junior Seau, Quentin Jammer, Ryan Matthews, Scott Mruczkowski, Antoine Cason, Kassim Osgood, Eric Parker, Keenan McCardell, Mike Goff, Marlon McCree, Jyles Tucker, Brandon McKinney, Greg Camarillo, Cletis Gordon Jr., Jeremy Sheffey, Tyronne Gross and Ron Rivera. ANTOINE CASON RyaN MatHEWS MIKE GOFF Scott MRUCZKOWSKI Defensive Back Running Back Former Guard Center San Diego Chargers San Diego Chargers San Diego Chargers San Diego Chargers The Antoine Cason Overnight and Commuter Football Camp gives you a very intense football training experience with Antoine Cason, an outstanding high school and college coaching staff and members of the San Diego Chargers. The Antoine Cason Day Camp offers some of the best, most intense football training available with an outstanding high school coaching staff and Antoine Cason. -

NFL Betting: Is the Market Efficient?

Skidmore College Creative Matter Economics Student Theses and Capstone Projects Economics 2017 NFL Betting: Is the Market Efficient? Mathew Marino Skidmore College Follow this and additional works at: https://creativematter.skidmore.edu/econ_studt_schol Part of the Other Economics Commons Recommended Citation Marino, Mathew, "NFL Betting: Is the Market Efficient?" (2017). Economics Student Theses and Capstone Projects. 27. https://creativematter.skidmore.edu/econ_studt_schol/27 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Economics at Creative Matter. It has been accepted for inclusion in Economics Student Theses and Capstone Projects by an authorized administrator of Creative Matter. For more information, please contact [email protected]. NFL Betting: Is the Market Efficient? By Mathew Marino A Thesis Submitted to Department of Economics Skidmore College In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirement for the B.A Degree Thesis Advisor: Qi Ge May 2, 2017 1 Abstract The Purpose of this research paper is to analyze the NFL point spread and Over/Under betting market and determine if it follows the efficient market hypothesis. This research paper uses data from armchairanalysis.com for the 2000 NFL season through the 2015 NFL season including playoffs. I use OLS and probit regressions in order to determine NFL betting market efficiency for the point spread betting market and the Over/Under betting market. The results indicate, that as a whole, the NFL betting market appears to be efficient. However, there may be behavioral tendencies that can be taken advantage of in order to make consistent betting profits. 2 I. Introduction According to Statista.com (2015), the sports gambling market has been estimated to be worth between $700 billion and $1 trillion, but the exact size is difficult to measure because it is not legal everywhere. -

Seahawks Look to Win Their Nfl-Leading 12Th-Straight

September 15, 2020 SEAHAWKS LOOK TO WIN THEIR NFL-LEADING 12TH-STRAIGHT HOME OPENER THIS WEEKEND Seattle looks to extend its NFL-leading home-opener winning streak to 2020 SCHEDULE 12 games this week as it takes on the New England Patriots. Kickoff is set Regular Season (1-0) for 5:20 p.m. (PT). Day Date Opponent W/L Score The Seahawks have won 16 of their last 17 home openers since 2003. Sun. 9/13 at Atlanta W 38-25 Since a 2008 loss, Seattle has won 11-straight home openers by a combined score of 259-94. Sun. 9/20 New England 5:20 p.m. NBC Sunday will mark Seattle’s first of four prime-time games this season Sun. 9/27 Dallas 1:25 p.m. FOX and since 2010, it is 10-4-1 on Sunday nights, holds a 19-3 home record in Sun. 10/4 at Miami 10:00 a.m. FOX prime-time and is an NFL-best 29-7-1 under the lights. Sun. 10/11 Minnesota* 5:20 p.m. NBC The two teams have split the last four regular season meetings, with Sun. 10/18 Bye Week Seattle winning two in a row, including the last meeting in November 2016. Sun. 10/25 at Arizona* 1:05 p.m. FOX Sun. 11/1 San Francisco* 1:25 p.m. FOX BROADCAST INFORMATION Sun. 11/8 at Buffalo* 10:00 a.m. FOX TV Network NBC Al Michaels (play-by-play) Sun. 11/15 at L.A. Rams* 1:25 p.m. -

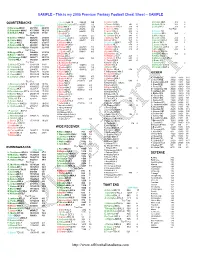

SAMPLE – This Is My 2005 Premium Fantasy Football Team Depth Chart – SAMPLE

SAMPLE - This is my 2005 Premium Fantasy Football Cheat Sheet – SAMPLE QUARTERBACKS T. Henry-TEN,10 326/45 0/0 K.Colbert-CAR, M.Pollard-DET, 309 6 D.Staley/W.Parker-PIT,4 830/55 1/0 A.Toomer-NYG,5 747 0 LJ.Smith-PHI,6 377 5 2004 Stats J.Bettis-PIT,4 941/46 13/0 J. McCareins-NYJ,8 770 4 D.Jolley-NYJ 313 2 P.Manning-IND,8 4577/38 49/0/10 D.Foster-CAR,7 255/76 2/0 P. Burress-NYG, 698 5 Tier Four D.Culpepper-MIN,5 4717/406 39/2/11 K.Barlow-SF,6 822/35 7/0 T. Glenn-DAL,9 400 2 B.Watson-NE D.McNabb-PHI,6 3875/220 31/3/8 F.Gore®-SF,6 M.Jenkins-ATL,8 119 0 D.Graham-NE,7 364 7 Tier Two L.Suggs-CLE,4 744/178 2/1 K. Johnson-DAL,9 981 6 B.Miller-HOU,3 K.Collins -OAK,5 3495/36 21/0/20 R.Droughns-CLE,4 1240/241 6/2 J.Galloway-TB,7 416 5 De.Clark-CHI,4 282 1 B. Favre-GB,6 4088/36 30/0/17 M.Turner-SD,10 392/17 3/0 B.Lloyd3-SF,6 565 6 J.Stevens-SEA,8 349 3 T. Green-KC,5 4591/85 27/0/17 R.Williams-MIA,4 M.Robinson-MIN,5 657 8 A.Becht-TB,7 100 1 C.Palmer-CIN,10 2897/47 18/1/18 E.Shelton®-CAR,7 D.Givens-NE,7 874 3 E.Conwell-NO,10 M.Hasselbeck-SEA,8 3382/90 22/1/15 M.Pittman-TB,7 926/391 7/3 R.Caldwell-SD,10 310 3 C.Anderson-OAK,5 128 1 Tier Three L.Johnson-KC,5 581/278 9/2 A.Bryant-CLE,4 812 4 A.Shea-CLE,4 252 4 G.Lewis®-PHI,6 E.Kinney-TEN,10 M.Bulger-STL,9 3964/89 21/3/14 T.J. -

O.F.E.L. League 2006 Transactions 05-Feb-2007 11:43 PM Eastern Week 1

www.rtsports.com O.F.E.L. League 2006 Transactions 05-Feb-2007 11:43 PM Eastern Week 1 Tue., Aug 1 2006 8:27 p Jo Jo's Jocks Acquired Minnesota Vikings MIN Def/ST Commissioner Tue., Aug 1 2006 8:27 p Jo Jo's Jocks Acquired Jay Feely NYG K Commissioner Tue., Aug 1 2006 8:27 p Jo Jo's Jocks Acquired Kris Brown HOU K Commissioner Tue., Aug 1 2006 8:27 p Jo Jo's Jocks Acquired Chris Cooley WAS TE Commissioner Tue., Aug 1 2006 8:27 p Jo Jo's Jocks Acquired Hines Ward PIT WR Commissioner Tue., Aug 1 2006 8:27 p Jo Jo's Jocks Acquired Donte' Stallworth PHI WR Commissioner Tue., Aug 1 2006 8:27 p Jo Jo's Jocks Acquired Santana Moss WAS WR Commissioner Tue., Aug 1 2006 8:27 p Jo Jo's Jocks Acquired Drew Bennett TEN WR Commissioner Tue., Aug 1 2006 8:27 p Jo Jo's Jocks Acquired Ahman Green GNB RB Commissioner Tue., Aug 1 2006 8:34 p Deer Slayer Acquired Seattle Seahawks SEA Def/ST Commissioner Tue., Aug 1 2006 8:34 p Deer Slayer Acquired Lawrence Tynes KAN K Commissioner Tue., Aug 1 2006 8:34 p Deer Slayer Acquired Kellen Winslow CLE TE Commissioner Tue., Aug 1 2006 8:34 p Deer Slayer Acquired Todd Heap BAL TE Commissioner Tue., Aug 1 2006 8:34 p Deer Slayer Acquired Joe Horn NOR WR Commissioner Tue., Aug 1 2006 8:34 p Deer Slayer Acquired Marvin Harrison IND WR Commissioner Tue., Aug 1 2006 8:34 p Deer Slayer Acquired Lee Evans BUF WR Commissioner Tue., Aug 1 2006 8:34 p Deer Slayer Acquired Nate Burleson SEA WR Commissioner Tue., Aug 1 2006 8:34 p Deer Slayer Acquired LenDale White TEN RB Commissioner Tue., Aug 1 2006 8:34 p Deer Slayer Acquired