Lotzer Brought Order to Potential Chaos in Cardwell No-Hitter Telecast

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Reinstate Buck Weaver to Major League Baseball Reinstate Buck Weaver to Major League Baseball Clearbuck.Com Update

Reinstate Buck Weaver to Major League Baseball Reinstate Buck Weaver to Major League Baseball ClearBuck.com Update Friday, May 21, 2004 Issue 6 ClearBuck.com on "The AL Central Today Show" Champs Who will win ClearBuck.com ambassadors the AL Central? battled the early morning cold Indians and ventured out to the Tribune plaza where "The Royals Today Show" taped live. Tigers Katie Couric and Al Roker helped celebrate the Twins destruction of the Bartman White ball with fellow Chicago Sox baseball fans. Look carefully in the audience for the neon green Clear Buck! signs. Thanks to Allison Donahue of Serafin & Associates for the 4:00 a.m. wakeup. [See Results] Black Sox historian objects to glorification of Comiskey You Can Help Statue condones Major League Baseball’s cover-up of 1919 World Series Download the Petition To the dismay of Black Sox historian and ClearBuck.com founder Dr. David Fletcher, Find Your Legislator the Chicago White Sox will honor franchise founder Charles A. Comiskey on April 22, Visit MLB for Official 2004 with a life-sized bronze statue. Information Contact Us According to White Sox chairman Jerry Reinsdorf, Comiskey ‘played an important role in the White Sox organization.’ Dr. Fletcher agrees. “Charles Comiskey engineered Visit Our Site the cover-up of one of the greatest scandals in sports history – the 1919 World Series Discussion Board Black Sox scandal. Honoring Charles Comiskey is like honoring Richard Nixon for his role in Watergate.” Photo Gallery Broadcast Media While Dr. Fletcher acknowledges Comiskey’s accomplishments as co-founder of the American League and the Chicago White Sox, his masterful cover-up of the series contributed to Buck Weaver’s banishment from Major League Baseball. -

Kit Young's Sale

KIT YOUNG’S SALE #20 Welcome to Kit Young’s Sale #20. Included in this sale are more fantastic sets from MAKE US The Barry Korngiebel Collection (and for the first time you can make us your best offer AN OFFER! For a limited time you can on them, please see below). Also included outstanding new arrivals, a 1939 Play Ball make us an offer on any set below set break, bargain priced baseball lots, ½ priced GAI graded cards, vintage wrapper (or any set on www.kityoung.com). specials and much more. You can order by phone, fax, email, regular mail or online We will either accept your offer through Paypal, Google Checkout or credit cards. If you have any questions or would or counter with a price more acceptable to both of us. like to email your order please email us at [email protected]. Our regular business hours are 8-6 Monday-Friday Pacific time. Toll Free #888-548-9686. 1960 TOPPS BASEBALL A 1962 TOPPS BASEBALL B COMPLETE SET EX-MT COMPLETE SET EX-MT Popular horizontally formatted set, loaded Awesome wood grain border set (including 9 variations) with stars and Hall of Famers. This set also loaded with stars and Hall of Famers. Overall grade of set includes a run of the tougher grey back series is EX-MT with many better and a few less. Includes Maris cards (#375-440 - 59 of 65 total). Overall #1 EX+/EX-MT, Koufax EX-MT, Clemente EX-MT/NR-MT, condition of set is EX-MT with many better Mantle/Mays #18 EX-MT, Banks EX-MT, B. -

Forgotten Heroes

Forgotten Heroes: Sam Hairston by Center for Negro League Baseball Research Dr. Layton Revel Copyright 2020 “Sam Hairston Night” – Colorado Springs (1955) “Sam Hairston Night” at the Colorado Springs Sky Sox Ball Park Sam Receives a New Car (1955) Hairston Family at Colorado Springs Ball Park “Sam Hairston Night” (front row left to right - Johnny, Sam Jr., Wife and Jerry) (1955) Samuel Harding Hairston was born on January 20, 1920 in the small town of Crawford, Lowndes County which is in the eastern part of the state of Mississippi. He was the second of thirteen children (eight boys and five girls) born to Will and Clara Hairston. Will Hairston moved his family from Crawford to the Birmingham area in 1922. The primary reason for the move was to find better work so that he could support his large family. Will became a coal miner and worked alongside Garnett Bankhead who was the father of the five Bankhead brothers who all played in the Negro Leagues. By 1930 Will had gained employment with American Cast Iron and Pipe (ACIPCO) as a laborer in their pipe shop. According to United States census records the Hairston family also lived in North Birmingham and Sayreton. Sam spent his formative years in Hooper City and attended Hooper City High School. Reportedly Sam did not finish high school and when he was 16 he told the employment office at ACIPCO that he was 18 and was given a job working for the company. According to Sam he went to work to help support the family and give his brothers and sisters the opportunity to go to school. -

Progressive Team Home Run Leaders of the Washington Nationals, Houston Astros, Los Angeles Angels and New York Yankees

Academic Forum 30 2012-13 Progressive Team Home Run Leaders of the Washington Nationals, Houston Astros, Los Angeles Angels and New York Yankees Fred Worth, Ph.D. Professor of Mathematics Abstract - In this paper, we will look at which players have been the career home run leaders for the Washington Nationals, Houston Astros, Los Angeles Angels and New York Yankees since the beginning of the organizations. Introduction Seven years ago, I published the progressive team home run leaders for the New York Mets and Chicago White Sox. I did similar research on additional teams and decided to publish four of those this year. I find this topic interesting for a variety of reasons. First, I simply enjoy baseball history. Of the four major sports (baseball, football, basketball and cricket), none has had its history so consistently studied, analyzed and mythologized as baseball. Secondly, I find it amusing to come across names of players that are either a vague memory or players I had never heard of before. The Nationals The Montreal Expos, along with the San Diego Padres, Kansas City Royals and Seattle Pilots debuted in 1969, the year that the major leagues introduced division play. The Pilots lasted a single year before becoming the Milwaukee Brewers. The Royals had a good deal of success, but then George Brett retired. Not much has gone well at Kauffman Stadium since. The Padres have been little noticed except for their horrid brown and mustard uniforms. They make up for it a little with their military tribute camouflage uniforms but otherwise carry on with little notice from anyone outside southern California. -

Insolvent Professional Sports Teams: a Historical Case Study

LCB_18_2_Art_2_Grow (Do Not Delete) 8/26/2014 6:25 AM INSOLVENT PROFESSIONAL SPORTS TEAMS: A HISTORICAL CASE STUDY by Nathaniel Grow* The U.S. professional sports industry has recently witnessed a series of high-profile bankruptcy proceedings involving teams from both Major League Baseball (“MLB”) and the National Hockey League (“NHL”). In some cases—most notably those involving MLB’s Los Angeles Dodgers and the NHL’s Phoenix Coyotes—these proceedings raised difficult issues regarding the proper balance for bankruptcy courts to strike between the authority of a professional sports league to control the disposition of its financially struggling franchise’s assets and the rights of the debtor team to maximize the value of its property. However, these cases did not mark the first time that a court was called upon to balance the interests of a professional sports league and one of its insolvent teams. Drawing upon original court records and contemporaneous newspaper accounts, this Article documents the history of two long-forgotten disputes in 1915 for the control of a pair of insolvent franchises in the Federal League of Professional Base Ball Clubs (specifically, the Kansas City Packers and the Indianapolis Hoosiers). In the process, the Article contends that despite the passage of time—and the different factual and procedural postures of the respective cases—courts both then and now have adopted similar approaches to managing litigation between professional sports leagues and their insolvent franchises. Moreover, the Article discusses how the history of these 1915 disputes helps explain why U.S. professional sports leagues have traditionally disfavored public franchise ownership. -

National Pastime a REVIEW of BASEBALL HISTORY

THE National Pastime A REVIEW OF BASEBALL HISTORY CONTENTS The Chicago Cubs' College of Coaches Richard J. Puerzer ................. 3 Dizzy Dean, Brownie for a Day Ronnie Joyner. .................. .. 18 The '62 Mets Keith Olbermann ................ .. 23 Professional Baseball and Football Brian McKenna. ................ •.. 26 Wallace Goldsmith, Sports Cartoonist '.' . Ed Brackett ..................... .. 33 About the Boston Pilgrims Bill Nowlin. ..................... .. 40 Danny Gardella and the Reserve Clause David Mandell, ,................. .. 41 Bringing Home the Bacon Jacob Pomrenke ................. .. 45 "Why, They'll Bet on a Foul Ball" Warren Corbett. ................. .. 54 Clemente's Entry into Organized Baseball Stew Thornley. ................. 61 The Winning Team Rob Edelman. ................... .. 72 Fascinating Aspects About Detroit Tiger Uniform Numbers Herm Krabbenhoft. .............. .. 77 Crossing Red River: Spring Training in Texas Frank Jackson ................... .. 85 The Windowbreakers: The 1947 Giants Steve Treder. .................... .. 92 Marathon Men: Rube and Cy Go the Distance Dan O'Brien .................... .. 95 I'm a Faster Man Than You Are, Heinie Zim Richard A. Smiley. ............... .. 97 Twilight at Ebbets Field Rory Costello 104 Was Roy Cullenbine a Better Batter than Joe DiMaggio? Walter Dunn Tucker 110 The 1945 All-Star Game Bill Nowlin 111 The First Unknown Soldier Bob Bailey 115 This Is Your Sport on Cocaine Steve Beitler 119 Sound BITES Darryl Brock 123 Death in the Ohio State League Craig -

Minor League Presidents

MINOR LEAGUE PRESIDENTS compiled by Tony Baseballs www.minorleaguebaseballs.com This document deals only with professional minor leagues (both independent and those affiliated with Major League Baseball) since the foundation of the National Association of Professional Baseball Leagues (popularly known as Minor League Baseball, or MiLB) in 1902. Collegiate Summer leagues, semi-pro leagues, and all other non-professional leagues are excluded, but encouraged! The information herein was compiled from several sources including the Encyclopedia of Minor League Baseball (2nd Ed.), Baseball Reference.com, Wikipedia, official league websites (most of which can be found under the umbrella of milb.com), and a great source for defunct leagues, Indy League Graveyard. I have no copyright on anything here, it's all public information, but it's never all been in one place before, in this layout. Copyrights belong to their respective owners, including but not limited to MLB, MiLB, and the independent leagues. The first section will list active leagues. Some have historical predecessors that will be found in the next section. LEAGUE ASSOCIATIONS The modern minor league system traces its roots to the formation of the National Association of Professional Baseball Leagues (NAPBL) in 1902, an umbrella organization that established league classifications and a salary structure in an agreement with Major League Baseball. The group simplified the name to “Minor League Baseball” in 1999. MINOR LEAGUE BASEBALL Patrick Powers, 1901 – 1909 Michael Sexton, 1910 – 1932 -

Kit Young's Sale #154

Page 1 KIT YOUNG’S SALE #154 AUTOGRAPHED BASEBALLS 500 Home Run Club 3000 Hit Club 300 Win Club Autographed Baseball Autographed Baseball Autographed Baseball (16 signatures) (18 signatures) (11 signatures) Rare ball includes Mickey Mantle, Ted Great names! Includes Willie Mays, Stan Musial, Eddie Murray, Craig Biggio, Scarce Ball. Includes Roger Clemens, Williams, Barry Bonds, Willie McCovey, Randy Johnson, Early Wynn, Nolan Ryan, Frank Robinson, Mike Schmidt, Jim Hank Aaron, Rod Carew, Paul Molitor, Rickey Henderson, Carl Yastrzemski, Steve Carlton, Gaylord Perry, Phil Niekro, Thome, Hank Aaron, Reggie Jackson, Warren Spahn, Tom Seaver, Don Sutton Eddie Murray, Frank Thomas, Rafael Wade Boggs, Tony Gwynn, Robin Yount, Pete Rose, Lou Brock, Dave Winfield, and Greg Maddux. Letter of authenticity Palmeiro, Harmon Killebrew, Ernie Banks, from JSA. Nice Condition $895.00 Willie Mays and Eddie Mathews. Letter of Cal Ripken, Al Kaline and George Brett. authenticity from JSA. EX-MT $1895.00 Letter of authenticity from JSA. EX-MT $1495.00 Other Autographed Baseballs (All balls grade EX-MT/NR-MT) Authentication company shown. 1. Johnny Bench (PSA/DNA) .........................................$99.00 2. Steve Garvey (PSA/DNA) ............................................ 59.95 3. Ben Grieve (Tristar) ..................................................... 21.95 4. Ken Griffey Jr. (Pro Sportsworld) ..............................299.95 5. Bill Madlock (Tristar) .................................................... 34.95 6. Mickey Mantle (Scoreboard, Inc.) ..............................695.00 7. Don Mattingly (PSA/DNA) ...........................................99.00 8. Willie Mays (PSA/DNA) .............................................295.00 9. Pete Rose (PSA/DNA) .................................................99.00 10. Nolan Ryan (Mill Creek Sports) ............................... 199.00 Other Autographed Baseballs (Sold as-is w/no authentication) All Time MLB Records Club 3000 Strike Out Club 11. -

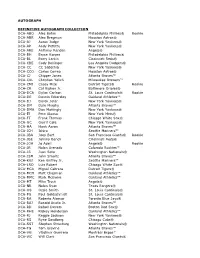

2021 Topps Definitive Collection BB Checklist.Xls

AUTOGRAPH DEFINITIVE AUTOGRAPH COLLECTION DCA-ABO Alec Bohm Philadelphia Phillies® Rookie DCA-ABR Alex Bregman Houston Astros® DCA-AJ Aaron Judge New York Yankees® DCA-AP Andy Pettitte New York Yankees® DCA-ARE Anthony Rendon Angels® DCA-BH Bryce Harper Philadelphia Phillies® DCA-BL Barry Larkin Cincinnati Reds® DCA-CBE Cody Bellinger Los Angeles Dodgers® DCA-CC CC Sabathia New York Yankees® DCA-CCO Carlos Correa Houston Astros® DCA-CJ Chipper Jones Atlanta Braves™ DCA-CKL Christian Yelich Milwaukee Brewers™ DCA-CMI Casey Mize Detroit Tigers® Rookie DCA-CR Cal Ripken Jr. Baltimore Orioles® DCA-DCA Dylan Carlson St. Louis Cardinals® Rookie DCA-DE Dennis Eckersley Oakland Athletics™ DCA-DJ Derek Jeter New York Yankees® DCA-DM Dale Murphy Atlanta Braves™ DCA-DMA Don Mattingly New York Yankees® DCA-EJ Pete Alonso New York Mets® DCA-FT Frank Thomas Chicago White Sox® DCA-GC Gerrit Cole New York Yankees® DCA-HA Hank Aaron Atlanta Braves™ DCA-ICH Ichiro Seattle Mariners™ DCA-JBA Joey Bart San Francisco Giants® Rookie DCA-JBE Johnny Bench Cincinnati Reds® DCA-JOA Jo Adell Angels® Rookie DCA-JR Nolan Arenado Colorado Rockies™ DCA-JS Juan Soto Washington Nationals® DCA-JSM John Smoltz Atlanta Braves™ DCA-KGJ Ken Griffey Jr. Seattle Mariners™ DCA-LRO Luis Robert Chicago White Sox® DCA-MCA Miguel Cabrera Detroit Tigers® DCA-MCH Matt Chapman Oakland Athletics™ DCA-MMC Mark McGwire Oakland Athletics™ DCA-MT Mike Trout Angels® DCA-NR Nolan Ryan Texas Rangers® DCA-OS Ozzie Smith St. Louis Cardinals® DCA-PG Paul Goldschmidt St. Louis Cardinals® DCA-RA Roberto Alomar Toronto Blue Jays® DCA-RAJ Ronald Acuña Jr. -

Kyle Schwarber, of – 1St Rd Draft 2014 • Ben Zobrist, LF – Free Agent 2016 • Addison Russell, SS – Trade, 2014 • Justin Heyward, of – Free Agent 2016 Jake Arrieta

The 2016 Chicago Cubs Agenda •The Cubs: 1900 – 2008 •2009 – The Ricketts Family buys the Team •The 2016 World Series Chicago Cubs Winning Percentage by Decade 1901-1910 11-20 21-30 31-40 41-50 .618 .533 .535 .569 .471 1951-1960 61-70 71-80 81-90 91-00 .434 .442 .474 .480 .468 2001-10 11-17 Total .504 .497 .512 Cubs Title Flags by Decades 1901-1910 11-20 21-30 31-40 41-50 2 WS/4 Pnt 1 Pnt 1 Pnt 3 Pnt 1 Pnt 1951-1960 61-70 71-80 81-90 91-00 0 0 0 2 Div 0 2001-10 11-17 Total 3 Div 1 WS/1 Pnt/2 Div 3 WS/11 Pnt/7 Div Cubs Cardinals Head to Head Record Over Time Cubs 1221 – Cardinals 1161 150 Cubs Cumulative wins over the years 100 50 1900 1910 1920 1930 1940 1950 1960 1970 1980 1990 2000 2010 Cubs – Cardinals: Championship Totals 20 15 10 5 0 Cubs Cardinals Wild Cards Division Titles Penants World Series Titles Both Teams Suffer a Common (Bad) Fate Cubs White Sox • Great teams from 1901-1919 • Great teams from 1901-1919 • 1901-2017: 9062-8867 (.509) • 1901-2017: 9149-9026 (.503) • Hall of Famers: 16 • Hall of Famers: 13 • Largest crowds in town for ~80 years • Largest crowds in town ~40 years • 11 Pennants / 3 WS • 6 Pennants / 3 WS • WS: 1906, 1908, 2016 (108 yrs) • WS: 1906, 1917, 2005 (88 yrs) Both Teams’ Fans Know How to Suffer • "If there is any justice in the world, to be a White Sox fan frees a man from any other form of penance." - Bill Veeck, Jr. -

My Replay Baseball Encyclopedia Fifth Edition- May 2014

My Replay Baseball Encyclopedia Fifth Edition- May 2014 A complete record of my full-season Replays of the 1908, 1952, 1956, 1960, 1966, 1967, 1975, and 1978 Major League seasons as well as the 1923 Negro National League season. This encyclopedia includes the following sections: • A list of no-hitters • A season-by season recap in the format of the Neft and Cohen Sports Encyclopedia- Baseball • Top ten single season performances in batting and pitching categories • Career top ten performances in batting and pitching categories • Complete career records for all batters • Complete career records for all pitchers Table of Contents Page 3 Introduction 4 No-hitter List 5 Neft and Cohen Sports Encyclopedia Baseball style season recaps 91 Single season record batting and pitching top tens 93 Career batting and pitching top tens 95 Batter Register 277 Pitcher Register Introduction My baseball board gaming history is a fairly typical one. I lusted after the various sports games advertised in the magazines until my mom finally relented and bought Strat-O-Matic Football for me in 1972. I got SOM’s baseball game a year later and I was hooked. I would get the new card set each year and attempt to play the in-progress season by moving the traded players around and turning ‘nameless player cards” into that year’s key rookies. I switched to APBA in the late ‘70’s because they started releasing some complete old season sets and the idea of playing with those really caught my fancy. Between then and the mid-nineties, I collected a lot of card sets. -

They're Gone a Decade, but Vince Lloyd's, Red Mottlow's Voices Remind of Eternal Friendships

They’re gone a decade, but Vince Lloyd’s, Red Mottlow’s voices remind of eternal friendships By George Castle, CBM Historian Posted Tuesday, February 19, 2013 Both great men are gone nearly 10 years. But I still consider them my friends, present tense, because I still hear their distinctive voices loud and clear, whether in memories of being on the air, offering wise counsel or only skimming the top of their encyclopedia of stories and ex- periences. I’ve got to keep their memory alive, because gen- erations who never heard them or knew them de- serve the benefit of their output as men and all- time sportscasters. Vince Lloyd and Red Mottlow had great influence on me growing up. As I got to know them closely as their senior-citizen days ap- proached and progressed, my only regret – a big Red Mottlow pounding away at his type- one -- is not getting more decades with them in writer with some of his broadcast corporeal form. awards on the wall behind him. Longtime baseball announcer Lloyd should be a recipient of the Ford C. Frick Award, honoring a great voice of the game. Pioneering radio sports reporter Mottlow should have gotten his shot on the air at WGN. Subtracting these goals doesn’t take a shred away from their lifetime achievements. There was Lloyd’s rich baritone, hardly cracking when he bellowed “Holy Mackeral!” for a Cubs homer, intersecting with Mottlow’s staccato, rapid-fire “Red Mottlow, WCFL Sports” on mid-20th Century 50,000-watt Chicago-originated frequencies. There were kind, encouraging words amid the most political of businesses – sports media -- where negativity and a childish caste system still rule.