Shoshin Ryu Yudanshakai Newsletter July/August 2011 Vol

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Owen County's Guardian Martial Arts Dojo Serves As Host Site For

Owen County’s Guardian Martial Arts Dojo Serves As Host Site For Karate Training Camp Small Circle Jujitsu Grandmaster Leon Jay Instructs Camp by Michael Stanley Staff Writer Professor Leon Jay, Grandmas- ter of Small Circle Jujitsu doesn’t exactly look to be in his 50’s, and he certainly doesn’t move like he’s 50. This was evident Saturday after- noon on the dojo floor of Guardian Martial Arts on Little Flock Road in rural southeastern Owen County. Professor Jay made a trip to Master Gary Cunningham’s per- sonal dojo from London, England, but first made a pit stop in Long Beach, California, where he met up with several other martial arts masters. The reasoning for their visit to Guardian Martial Arts wasn’t just to catch up, but to train as part of the Professor Jay’s Small Circle Jujitsu 2009 Midwest Camp as nearly 100 martial art- ists were in attendance to learn from the very best. “It was the first of its kind and the first camp here at Guardian Grandmaster of Small Circle Jujitsu Professor Leon Jay (left) uses a finger lock to remove a Martial Arts. Most training camps knife from the hand of Master Norm Johnson of Maui, Hawaii. Jay made a trip from London, Eng- are held at hotels and the “dojo” is land to the Little Flock Road dojo of Master Gary Cunningham last Saturday to teach a two-day a cleared out meeting room,” Cun- camp in Small Circle Jujitsu. (Staff Photo by Michael Stanley) ningham explained. “The training father, Professor and founder of floor here at Guardian Martial Arts Small Circle Jujitsu Grandmaster is a dream for any practitioner who Wally Jay. -

Sandan 3Rd Degree Black Belt…. Student’S Responsibility: Black Belts Must Start a Journal Two Months Prior to Testing

www.EversonsKarateInstitute.com Sandan 3rd Degree Black Belt…. Student’s responsibility: Black Belts must start a journal two months prior to testing. Once a week write in your journal what you have been practicing each week until black belt testing. Your journal must be completed, signed weekly by a parent and turned in with your testing notice. SANDAN 3rd DEGREE BLACK BELT CURRICULUM 1. 36 month of training after Nidan 2nd degree 2. 130 Teaching Classes from 2nd degree Black Belt. 3. Student must choose a weapon and create a kata. Everson's Karate Institute Theory and Technique: 1. The history of the Martial Arts: Know what Martial Arts and its history that Master Everson has incorporated to form Everson's Karate Institute. 2. The philosophy of Everson’s Karate Institute. 3. Study of basic structure of kicks good structure and kicking techniques will make you stronger and improve your kicking precision. Good theories allow you to fight smarter not harder. 4. Study of basic structure and theories of Jiu-Jitsu (Self-Defense) Good structure and hand techniques will make you stronger and improve your coordination. Good theories allow you to fight smarter not harder. 5. Study of basic structure and theories of Kempo (Striking Points) Good structure and technique will make you stronger and improve your precision. Good theories allow you to fight smarter not harder. All the above answers can be found in many different books. Here are some examples: The Dillman Method of Pressure Points and Jujitsu Wally Jay. 1. Katas one thru nine: Know the basic structure, break down and theories of the moves. -

2018Bsdcatalog Web3.Pdf

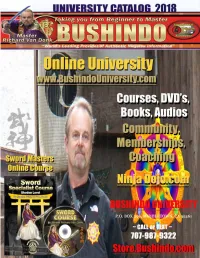

BUSHINDOTM - YOUR BUJINKAN INFORMATION SOURCE WHAT’S INSIDE FIND IT HERE FAST! What’s inside / Where to Start pages 2-4 About Soke Hatsumi page 28 Bushindo University page 5 Soke Hatsumi USA Tai Kai DVDs page 29 About Master Van Donk page 6 Soke Hatsumi Books / Translations page 30 IBDA Training Opportunities pages 7-11 Ninja Dojo Online Training page 31 Ninjutsu Masters Course pages 12-13 DeCuerdas Eskrima Course pages 32-35 Black Belt Home Study Course pages 14-17 Sword Masters Course pages 36-37 Shidoshi Training Course page 18 Empowerment Course - University Online pages 38-39 Budo Taijutsu Course page 19 Spiritual Courses RVD - Body Rejuvenation pages 40-41 2nd - 4th Degree Black Belt Courses page 20 Kuji, Mikkyo, Meditation pages 42-43 Ninjutsu Made Easy DVD Series pages 21-22 Bushindo Rejuvenation - Enlightened Warrior page 44 Van Donk Mastering Ninjutsu DVDs page 23 Training Gear Section pages 45-47 Master Van Donk Books page 24 What Others Say About Us page 48 Ninjutsu Weapons Course page 25 Your Paradigm Shift Opportunity page 49 Warrior Secrets Tai Kai Set page 26 Order Form page 50 Best Sellers / Takamatsu DVD page 27 Dear Friends and fellow martial artists, Thank you for your continued interest and support! We at Bushindo University/International Bujinkan Dojo Association are dedicated to helping you and others around the world more easily obtain quality Life Changing studies, including martial arts like Bujinkan Ninjutsu/Budo Taijutsu, DeCuerdas Eskrima, Bushindo Sword and Enlightened Warrior Teachings. We provide our students and friends direct lineage access to Soke Masaaki Hatsumi in Japan. -

2010 – US Martial Arts Hall of Fame Inductees

Year 2010 – US Martial Arts Hall of Fame Inductees Alaska Annette Hannah……………………………………………...Female Instructor of the year Ms. Hannah is a 2nd degree black belt in Shaolin Kempo. She has also studied Tae kwon do, and is a member of ISSKA. Ms. Hannah has received two appreciation awards from the U.S. Army, and numerous sparring trophies. She is also proud to provide service to help the U.S. soldiers and their families that sacrifice to keep this country safe and risk their lives for all of us. James Grady …………………………………………………………………………….Master Mr. Grady is a member of The Alaska Martial Arts Association and all Japan Karate Do Renbukai. Mr. Grady is a 6th Dan in Renbukan California William Aguon Guinto ………………………………………………………..Grandmaster Mr. Guinto has studied the art for 40 years he is the owner and founder of Brown Dragon Kenpo. He has training in the styles of Aiki do, Kyokoshihkai, tae kwon do, and Kenpo. Mr. Guinto is a 10th Grandmaster in Brown Dragon Kenpo Karate and has received awards in Kenpo International Hall of Fame 2007 and Master Hall of Fame Silver Life. He is a member of U.S.A. Martial Arts Alliance and International Martial Arts Alliance. Steven P. Ross ………………………………………………Master Instructor of the year Mr. Ross has received awards in 1986 World Championship, London England, numerous State, Regional and National Championships from 1978 thru 1998, Employee of the Year 2004, and principal for the day at a local high school. He was formerly a member of The US Soo Bahk Do, and Moo Duk Kwan Federation. -

Small-Circle Jujitsu Pdf, Epub, Ebook

SMALL-CIRCLE JUJITSU PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Wally Jay | 256 pages | 01 Aug 1989 | Black Belt Communications | 9780897501224 | English | Santa Clarita, CA, United States Small-circle Jujitsu PDF Book He also teaches judo at the Academy of Art University, the only art school in the country with a judo program. Other editions. Presas who's innovative methods remind me of Prof. He produced many medalists in national judo championships, such as Bradford Burgo and David Quinonez, who won national high school titles in and respectively. Energy Transfer 7. We are the premier destination for self defense based instruction. Jay is a 10th Degree Black Belt in jujitsu and has received awards such as coach of the year for competitions. Many had recognized the small circle system as being a separate style for many years, but after an article in Black Belt magazine, it was official. Jay authored two books, Small Circle Jujitsu and Dynamic Jujitsu, as well as five instructional videos. Paperback , pages. Esoteric Principles. Photos present most of the information. The activity is NOT strenuous and modifications will be given for those with injury or limitation. Kata Rules and Regulation. Mondays and Wednesday pm to pm. Sport's never mentioned. He has also realized that some of the Judo practitioners would use the effective throwing techniques against the opponents that are bigger then they are, with absolutely no effort at all. President's Message. Small-Circle Jujitsu. This wrist action is prevalent in Small Circle Jujitsu techniques and over the years Wally Jay made radical changes in the techniques he acquired. -

The Historical Timeline of Danzan Ryu Jujitsu

The Historical Timeline of Danzan Ryu Jujitsu Revised: November 25, 2018 The Historical Timeline of Danzan Ryu Jujitsu is not a copyrighted document. It is being made available free of charge to the Danzan Ryu community for historical and educational purposes. The history of Danzan Ryu does not belong to any one person. It belongs to the Danzan Ryu family – our Ohana. All entries are based on information obtained from historical documents, newspaper articles, personal interviews, Danzan Ryu newsletters and website postings from many of the Danzan Ryu organizations. A very special thanks goes out to Professor Mike Chubb for his assistance and with providing me with historical Danzan Ryu information he has researched and collected over the years. Some of the Danzan Ryu Professors who provided historical information and helped with this project include: American Jujitsu Institute Professors Sam C. Luke, Ken Eddy and Danny Saragosa. American Judo & Jujitsu Federation Professors Jane Carr, John Congistre, Dennis Estes, Tom Hill, Robert Hodgkin, Tom Jenkins, Geoff Lane and Larry Nolte. Bushidokan Federation Professors Herb LaGue, Robert Karnes, and Victor Manica. Christian Jujitsu Association Professor Gene Edwards Jujitsu America Professor Joe Souza Kilohana Martial Arts Association Professors Russ Coelho, Steve Barber, Mike Esmailzadeh, Hans Ingebretsen and James Muro. Kodenkan Yudanshakai Shihan Vinson Holck and Irene Swanson. Pacific Jujitsu Alliance Professors Kevin Colton and Troy Shehorn. Shoshin Ryu Yudanshakai Professors Mike, Chubb, Maureen Browne, William Fischer, Barbara Gessner, Ron Jennings, Sue Jennings, Barry Posner, Rory Rebmann and Bryan Stanley. The Historical Timeline of Danzan Ryu Jujitsu is a living document supported by information provided by the Danzan Ryu community. -

KT 2-3-2015 Layout 1

SUBSCRIPTION MONDAY, MARCH 2, 2015 JAMADA ALAWWAL 11, 1436 AH www.kuwaittimes.net Three children Netanyahu Leaders Mighty Terry killed in Saad takes off of Egypt, inspires Chelsea Al-Abdullah on ‘historic’ Turkey visit to League apartment5 fire US mission8 Saudi13 Arabia Cup20 glory ‘Jihadi John’ loses his Min 09º Max 28º edge after unmasking High Tide 10:08 & 20:14 Low Tide Emwazi’s relatives under watch in Kuwait 03:33 & 14:40 40 PAGES NO: 16447 150 FILS LONDON/ KUWAIT: As “Jihadi John”, he was a terrifying figure, his identity concealed by a black mask, his threat- Amir thanks people for ening tone backed up by his oversize, serrated knife and his willingness to use it in the name of Islamic State and its self-declared caliphate. His professional-looking national celebrations videos began with a political rant and ended with his vic- KUWAIT: HH the Amir Sheikh Sabah Al- two occasions, noting their admirable tims lying dead at his feet, severed heads cupped in the Ahmad Al-Jaber Al-Sabah thanked the stances vis-a-vis Kuwait during the times of sands of Syria. He seemed both judge and executioner, Kuwaiti people and expatriates living in independence and liberation, emphasizing savoring each fresh kill. Kuwait for their warm cele- that these stances would be After the 9/11 attacks on the US, many believed that brations of the independ- indelibly burnished in the terrorists would turn to crude weapons of mass destruc- ence and liberation days. HH collective memory of the tions to attack cities. Few predicted that a man with a the Amir also thanked gov- Kuwaiti nation. -

The Professors of Danzan Ryu Jujitsu

The Professors of Danzan Ryu Jujitsu Written by Robert McKean Monday, 28 June 2010 00:00 Many of the classical Japanese martial arts use titles such as Renshi (trainer or assistant instructor), Kyoshi (doctrinal teacher or instructor), Hanshi (model teacher or master) and Shihan (master) for the higher ranking members of their particular ryu. So why is the title of Professor used in Danzan Ryu and where did it come from? Master Henry Seishiro Okazaki was known by his students and the local Hawaiian community as “The Professor.” The title of Professor is said to have originated with some of Professor Okazaki’s early American (Caucasian) students. They began calling him Professor him out of respect for his knowledge, ability and willingness to teach his ryu to many different people. Professor is a western title and honor that, to them, came close to the martial art title of Shihan or Master. This titled, borrowed from the Western academic tradition, had long been applied to high-ranking Japanese martial artists. For example, there was “Professor” John J. O’Brien, who received his diploma in Jui Jitsu in 1905 from the Governor of Nagasaki and who introduced President Teddy Roosevelt to Jiu Jitsu. There was also “Professor” Kishoku Inouye, the man who taught H. Irving Hancock, author of the 1905 book, The Complete Kano Jiu-Jitsu (Judo). Being credited as one of the first Japanese martial arts instructors to break away from many of the old Japanese traditions by teaching non-Asian students, Professor Okazaki willingly embraced the Western title of Professor. -

Kilohana Martial Arts Association Kilohana CHRONICLES Volume 9 Issue 1 1St Quarter 2009 Greetings from the President the Beginning of a New Year Come and Go

A Publication of Kilohana Martial Arts Association KilohanA CHRONICLES Volume 9 Issue 1 1st Quarter 2009 Greetings From the President The beginning of a new year come and go. Many leave just when is always a good time to take stock they are on the brink of some kind Table of and remind ourselves what we are of breakthrough, or when they are after, what our goals are, and it is a faced with a challenge that seems Contents good time to set a business plan to overly daunting. A select few re - Greetings from 1 implement our goals. main and continue to the President Have you ever consid - study for years and ered making a business years, and slowly they plan for your martial 2009 Kilohana 3 find the art expressing studies? Simply having itself in them and Calendar of Events goals is fine, but you through them. Some must envision how you stick around for years, Historical Focus 8 intend to accomplish but only train when it is on Healing and your goals; and if you convenient or pleasing. Danzan Ryu do not have specific Now look again at goals, perhaps you are your sensei. This is January Ku’i Lima 14 leaving too much to most likely a person Workout chance. Those who are who devotes a great successful in any en - Three of Kilohana’s amount of effort into British and 16 deavor are the ones Founding Members: the development of oth - who know what they Dai Shihan Sig Kufferath(center) European Kilohana with his students Kilohana President, ers, and who takes a want, and then let Sensei Hans Ingebretsen (left), and personal interest in Gasshuku Kilohana Standards Board member nothing get in the way and former Secretary and Sgt. -

Volume 8 Issue 1 1St Quarter 2008

Volume 8 Issue 1 1st Quarter 2008 Professor Imi Okazaki-Mullins It is with deep sadness that we say goodbye to Professor Louise “Imi” Okazaki-Mullins, a woman who has kept the integrity of her father’s ju jitsu system intact, and who, through the strength of her character, led the rest of us to examine ourselves and our commitment to Danzan Ryu in a direct and honest manner. She held herself to the highest of standards, and expected those who study her father’s system to do the same. Those who were blessed to know her saw the embodiment of a true lady - Imi was a class act, poised and always in perfect control. From ju jitsu to taiko drumming, she approached all that she did with sincereity and commitment. We are all better off for having had her in our lives. -Sensei Hans Ingebretsen Photo courtesy of usadojo.com A very young Professor Mullins in front of her father, Professor Henry Bing Fai Lau and Imi Okazaki-Mullins Seishiro Okazaki 1 s we enter our second decade, Kilohana is growing and conAtinually changing, yet still we remain true to our roots and our core values. Formed originally by those of us who were drawn to Professor Sig Kufferath, we found a sense of community in our training together and a sense of excitement in the new venture we were undertaking by forming KIlohana. Vital to our endeavor is the sense that we are continually challenging ourselves to ex - plore deeper realms of our commitment to our art. This is essen - tially the basis for what a martial life is - an honest and revealing look at ourselves and how we relate to others. -

Le Petit Dragon.Wps

Bruce Lee, né le 27 novembre 1940 -année du Dragon, avec les premières lueurs de l'aube, au Jackson Street Hospital, dans le Chinatown de San Francisco. Son père Lee Hoi Chuen: Comédien, vedette de l'opéra de canton, est en tourné à New York, à près de cinq mille kilomètres, à l'Est, et le reste de sa famille - Son frère, 1 ses deux sœurs et ses grands-parents - se trouve à Hong Kong, à plus de huit milles kilomètres dans la direction opposée. On comprend alors que la petite eurasienne d'origine allemande, du nom de Grace Li, qui vient de mettre au monde son quatrième enfant, se sente perdue, isolée, fragile étrangère en terre étrangère et qu’elle désire avant tout s’attirer la bienveillance des dieux: Elle lui donne le nom de Li Jun Fan. Li se transforme alors très vite en son homonyme américain Lee, Jun Fan, qui signifie «Protecteur de San 2 Francisco». Le petit Lee se retrouve affublé d’un prénom féminin signifiant «petit Phénix». C’est une ruse imaginée par sa famille pour tromper les démons qui volent, aux premières heures du jour, les enfants males, et Lee le conserve, jusqu'à ce, des années plus tard, lui revienne le surnom, justifié par sa naissance, aussi bien que 3 par son tempérament, de Hsui Loong, « le Petit Dragon » Quant au prénom, que Marie Glover: l'infirmière de la maternité lui avait donné pour l’américaniser, Bruce ne l’entend prononcer que treize ans plus tard, lors de son inscription dans une école anglaise de son pays. -

Hi! Who Can Come? Prices: Eating: Sign In: Questions: Sleeping

Hi! Some information about the seminar with Ed Melaugh 8. Dan Small Circle jujitsu The seminar is: Saturday 22 September from 10.00 o´clock on the floor to17.00. Sign in and Breakfast from 09.00 o´clock Who can come? The seminar is for experienced Martial artists with a minimum of 4 years in traditional Martial arts and more than 18 years old Prices: Seminar including breakfast and lunch 60 Euro members 70 Euro non member Eating: Saturday we plan to eat at the local Chinese restaurant the price is about 25 euro buffet and drink. In order for us to have room enough please tell if you like to join Sign in: Please mail me here [email protected] Questions: Feel free to call me at this number Tlf.: +4523424987 Sleeping: We have a wonderful club fell free to stay there all the days. Where are we: Danmarksgade 45 Esbjerg Denmark Sensei Ed Melaugh's Professional Background Sensei Ed Melaugh has the honor of being a Soke Dai (Inheritor) to Small Circle Jujitsu, hand picked by the founder of Small Circle JuJitsu, Professor Wally Jay. Sensei Melaugh's association with Professor Jay began in 1978. From Professor Jay, he learned to use simple, efficient motions and to attack the opponent's weaker body parts, such as fingers, wrists, and Golgi tendon in the arm. Using small, efficient circular motions and the Small Circle Ten Principles, he could cause pain to render the largest person helpless without causing injury. Sensei Melaugh was promoted by Professor Jay to Eighth Degree Black Belt in Small Circle Jujitsu.