Guide to Infection Control in the Healthcare Setting

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

S. Pneumoniae + Legionella Detection Kit

S. pneumoniae + Legionella detection kit Pathogen and product description Gram positive bacteria Streptococcus pneumoniae antimicrobial therapy is institutedted earlearly.y. KKnownnown is one of the most important pathogen that risk factors include immunosuppression,pressiiitton, ccigaretteigarette affects mainly children and elderly and can smoking, alcohol consumption andditt concomitant cause life-threatening diseases. Streptococcus pulmonary disease. Legionella pneumophila is pneumoniae infection leads to many clinical responsible for 80-90% of reported cases of manifestations including meningitis, septicaemia, Legionella infection with serogroup 1 accounting bacteraemia, pneumonia, acute otitis media and for greater than 70% of all legionellosis. sinusitis. Pneumococcal infection annually has CerTest Streptococcus pneumoniae + Legionella caused approximately 14.5 million cases of invasive one step card test offers a simple and highly pneumococcal disease (IPD) and 0.7-1 million sensitive assay to make a presumptive diagnosis deaths in children under five years old, mostly in of pneumoniae and/or Legionella caused by developing and underdeveloped countries. Streptococcus pneumoniae and/or Legionella Legionnaires’ Disease is caused by Legionella pneumophila in infected humans from urine samples. pneumophila and is characterized as an acute febrile respiratory illness ranging in severity from mild illness to fatal pneumonia. The resulting mortality rate, ranging from 25 to 40% can be lowered if the disease is diagnosed rapidly and appropriate S. pneumoniae + Legionella detection kit Test procedure step 1 Using a separate testing tube or vial for each sample, step 2 Add 2 drops of Reagent step 3 Use a separate pipette and device for each sample or add 6 drops of urine sample. into the testing tube or vial control. -

Implications for Pandemic Influenza Preparedness

ImpactImpact ofof ConjugateConjugate PneumococcalPneumococcal VaccineVaccine onon PneumococcalPneumococcal Pneumonia:Pneumonia: ImplicationsImplications forfor PandemicPandemic InfluenzaInfluenza PreparednessPreparedness KeithKeith P.P. KlugmanKlugman DepartmentDepartment ofof GlobalGlobal Health,Health, RollinsRollins SchoolSchool ofof PublicPublic HealthHealth andand DivisionDivision ofof InfectiousInfectious Diseases,Diseases, SchoolSchool ofof MedicineMedicine EmoryEmory University,University, Atlanta,Atlanta, USAUSA AcuteAcute respiratoryrespiratory infectionsinfections –– thethe leadingleading infectiousinfectious causecause ofof deathdeath 4.0 3.5 3.0 Over age five Under age five 2.5 * HIV-positive people 2.0 who have died with TB have been 1.5 included among AIDS deaths Millions of deaths 1.0 0.5 0 Acute AIDS* Diarrhoeal TB Malaria Measles respiratory diseases infections Estimates for adults 2002; under 5’s 2000-2003; World Health Report 2004/52 CommunityCommunity AcquiredAcquired PneumoniaPneumonia frequencyfrequency byby ageage // 10001000 40 35 30 25 20 15 10 5 0 << 55 55 -- 14 14 1515 -- 29 29 3030 -- 44 44 4545 -- 59 59 6060 -- 74 74 >> 7474 AgeAge (years)(years) Jokinen et al. Am J Epidemiol 1993;137:977-988 Jokinen et al. Am J Epidemiol 1993;137:977-988 3 BacterialBacterial EtiologyEtiology ofof CommunityCommunity-- AcquiredAcquired PneumoniaPneumonia Atypical pathogens: Legionella spp S. pneumoniae Chlamydia spp Mycoplasma spp 22% 34% 6% S. aureus 15% 15% Other 8% H. influenzae and M. catarrhalis Aerobic gram-negative -

Allergy, Immunity, and Infection, and Respiratory Joint Session

A86 Arch Dis Child 2005;90(Suppl II):A86–A88 Methods: We performed a retrospective case note review Allergy, immunity, and infection, of all children with cystic fibrosis treated with voriconazole in a single tertiary paediatric centre over an 18 month period. and respiratory joint session Results: A total of 21 children aged 5 to 16 years (median 11.3) received voriconazole for between 1 and 50 (22) weeks. Voriconazole was used in two children with recurrent ABPA and a history of G227 THE CLINICO-EPIDEMIOLOGICAL BURDEN OF previous steroid treatment as monotherapy; significant, and Arch Dis Child: first published as on 21 March 2005. Downloaded from INFLUENZA IN INFANTS AND YOUNG CHILDREN IN sustained improvements in clinical and serological parameters EAST LONDON, UK for up to 13 months were observed, without recourse to further oral steroids. Voriconazole was used in combination with an 1, 3 1 1 2 1 E. K. Ajayi-Obe , P. G. Coen , R. Handa , K. Hawrami , S. Mieres , immunomodulatory agent (oral corticosteroids in nine, metho- 2 4, 5 1 1 C. Aitken , E. D. G. McIntosh , R. Booy . Center of Child Health, Queen trexate in one case, and intravenous immunoglobulin in another) Mary University of London, Barts and the London NHS Trust, London, UK; in a further 11 children with ABPA, with significant improve- 2 Department of Virology, Queen Mary University of London, Barts and the ment in pulmonary function and serology. Eight children who did 3 London NHS Trust, London, UK; Department of Paediatrics, Hammersmith not meet the criteria for ABPA but had recurrent Aspergillus 4 Hospitals NHS Trust, London, UK; Faculty of Medicine, Imperial College of fumigatus isolates and an increase in symptoms also received 5 Science, Medicine and Technology , London, UK; Wyeth, UK, Huntercombe, voriconazole; children in this group did not an improve with treat- UK ment. -

Comparative Radiographic Features of Community Acquired Legionnaires' Disease, Pneumococcal Pneumonia, Mycoplasma Pneumonia, and Psittacosis

Thorax: first published as 10.1136/thx.39.1.28 on 1 January 1984. Downloaded from Thorax 1984;39:28-33 Comparative radiographic features of community acquired legionnaires' disease, pneumococcal pneumonia, mycoplasma pneumonia, and psittacosis JT MACFARLANE, AC MILLER, WH RODERICK SMITH, AH MORRIS, DH ROSE From the Departments of Thoracic Medicine and Radiology, City Hospital, Nottingham ABSTRACT The features of the chest radiographs of 49 adults with legionnaires' disease were compared with those of 91 adults with pneumococcal pneumonia (31 of whom had bacteraemia or antigenaemia), 46 with mycoplasma pneumonia, and 10 with psittacosis pneumonia. No distinctive pattern was seen for any group. Homogeneous shadowing was more frequent in legionnaires' disease (40/49 cases) (p < 0.005), bacteraemic pneumococcal pneumonia (25/31) (p < 0.01) and non-bacteraemic pneumococcal pneumonia (42/60) (p < 0.05) than in myco- plasma pneumonia (23/46). Multilobe disease at presentation was commoner in bacteraemic pneumococcal pneumonia (20/31) than in non-bacteraemic pneumococcal pneumonia (15/60) (p < 0.001) or legionnaires' disease (19/49) (p < 0.025). In bacteraemic pneumococcal pneumonia multilobe disease at presentation was associated with increased mortality. Pleural effusions and some degree of lung collapse were seen in all groups, although effusions were commoner in bacteraemic pneumococcal pneumonia. Cavitation was unusual. Lymphadenopathy occurred only in mycoplasma pneumonia (10/46). Radiographic deterioration was particularly a feature of legionnaires' disease (30/46) and bacteraemic pneumococcal pneumonia (14/27), and these groups also showed slow radiographic resolution in survivors. Radiographic resolution was fastest with mycoplasma pneumonia; psittacosis and non-bacteraemic pneumococcal pneumonia http://thorax.bmj.com/ cleared at an intermediate rate. -

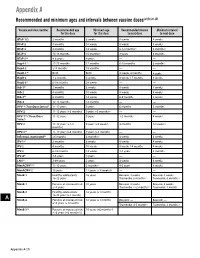

Recommended and Minimum Ages and Intervals Between Doses

Appendix A Recommended and minimum ages and intervals between vaccine doses(a),(b),(c),(d) Vaccine and dose number Recommended age Minimum age Recommended interval Minimum interval for this dose for this dose to next dose to next dose DTaP-1(e) 2 months 6 weeks 8 weeks 4 weeks DTaP-2 4 months 10 weeks 8 weeks 4 weeks DTaP-3 6 months 14 weeks 6-12 months(f) 6 months(f) DTaP-4 15-18 months 15 months(f) 3 years 6 months DTaP-5(g) 4-6 years 4 years — — HepA-1(e) 12-23 months 12 months 6-18 months 6 months HepA-2 ≥18 months 18 months — — HepB-1(h) Birth Birth 4 weeks-4 months 4 weeks HepB-2 1-2 months 4 weeks 8 weeks-17 months 8 weeks HepB-3(i) 6-18 months 24 weeks — — Hib-1(j) 2 months 6 weeks 8 weeks 4 weeks Hib-2 4 months 10 weeks 8 weeks 4 weeks Hib-3(k) 6 months 14 weeks 6-9 months 8 weeks Hib-4 12-15 months 12 months — — HPV-1 (Two-Dose Series)(l) 11-12 years 9 years 6 months 5 months HPV-2 11-12 years (+6 months) 9 years +5 months(m) — — HPV-1(n) (Three-Dose 11-12 years 9 years 1-2 months 4 weeks Series) HPV-2 11-12 years (+1-2 9 years (+4 weeks) 4 months 12 weeks (n) months) HPV-3(n) 11-12 years (+6 months) 9 years (+5 months) — — Influenza, inactivated(o) ≥6 months 6 months(p) 4 weeks 4 weeks IPV-1(e) 2 months 6 weeks 8 weeks 4 weeks IPV-2 4 months 10 weeks 8 weeks-14 months 4 weeks IPV-3 6-18 months 14 weeks 3-5 years 6 months IPV-4(q) 4-6 years 4 years — — LAIV(o) 2-49 years 2 years 4 weeks 4 weeks MenACWY-1(r) 11-12 years 2 months(s) 4-5 years 8 weeks MenACWY-2 16 years 11 years (+ 8 weeks)(t) — — MenB-1 Healthy adolescents: 16 -

Pneumococcal Disease (Sickness Caused by Streptococcus Pneumoniae)

Pneumococcal Disease (Sickness Caused by Streptococcus pneumoniae) What is pneumococcal disease? Pneumococcal disease is an infection caused by the bacteria Streptococcus pneumoniae. It's also called pneumococcus and can cause ear infections, pneumonia, infections in the blood and meningitis. When does it happen? Children can get pneumococcal disease any time of the year. What are the symptoms? Fever and increased fussiness or irritability are common Meningitis symptoms include fever, trouble bending or moving the neck, increased fussiness or irritability, and headache in anyone over age 2. In babies, the only symptoms may be that the baby is less active, fussy or crying more than usual, throwing up, or not eating normally. Pneumonia symptoms in children include fever, cough, working hard to breathe, breathing faster than usual or grunting. Ear infection symptoms are ears that hurt, crying or pulling on ears, sore throat or pain when swallowing. Children may also be sleepy, have a fever, and be fussy. Is it contagious? How is it spread? Pneumococcus is spread by contact with people who either have a pneumococcal illness or who carry the bacteria in their throats without being sick. It can be spread by droplets in the air from coughing or sneezing. It can also be spread if you touch something that has the droplets on it, and then touch your own nose, mouth or eyes. How bad is pneumococcal disease? Pneumococcal disease can be very bad for young children and is the most common cause of meningitis and bacterial pneumonia in children. How can pneumococcal disease be avoided in children? There is a vaccine that can help stop serious pneumococcal disease, such as meningitis and blood infections. -

IDSA/ATS Consensus Guidelines on The

SUPPLEMENT ARTICLE Infectious Diseases Society of America/American Thoracic Society Consensus Guidelines on the Management of Community-Acquired Pneumonia in Adults Lionel A. Mandell,1,a Richard G. Wunderink,2,a Antonio Anzueto,3,4 John G. Bartlett,7 G. Douglas Campbell,8 Nathan C. Dean,9,10 Scott F. Dowell,11 Thomas M. File, Jr.12,13 Daniel M. Musher,5,6 Michael S. Niederman,14,15 Antonio Torres,16 and Cynthia G. Whitney11 1McMaster University Medical School, Hamilton, Ontario, Canada; 2Northwestern University Feinberg School of Medicine, Chicago, Illinois; 3University of Texas Health Science Center and 4South Texas Veterans Health Care System, San Antonio, and 5Michael E. DeBakey Veterans Affairs Medical Center and 6Baylor College of Medicine, Houston, Texas; 7Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine, Baltimore, Maryland; 8Division of Pulmonary, Critical Care, and Sleep Medicine, University of Mississippi School of Medicine, Jackson; 9Division of Pulmonary and Critical Care Medicine, LDS Hospital, and 10University of Utah, Salt Lake City, Utah; 11Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Atlanta, Georgia; 12Northeastern Ohio Universities College of Medicine, Rootstown, and 13Summa Health System, Akron, Ohio; 14State University of New York at Stony Brook, Stony Brook, and 15Department of Medicine, Winthrop University Hospital, Mineola, New York; and 16Cap de Servei de Pneumologia i Alle`rgia Respirato`ria, Institut Clı´nic del To`rax, Hospital Clı´nic de Barcelona, Facultat de Medicina, Universitat de Barcelona, Institut d’Investigacions Biome`diques August Pi i Sunyer, CIBER CB06/06/0028, Barcelona, Spain. EXECUTIVE SUMMARY priate starting point for consultation by specialists. Substantial overlap exists among the patients whom Improving the care of adult patients with community- these guidelines address and those discussed in the re- acquired pneumonia (CAP) has been the focus of many cently published guidelines for health care–associated different organizations, and several have developed pneumonia (HCAP). -

Allergic Inflammation Alters the Lung Microbiome and Hinders Synergistic

www.nature.com/scientificreports OPEN Allergic infammation alters the lung microbiome and hinders synergistic co-infection with H1N1 infuenza virus and Streptococcus pneumoniae in C57BL/6 mice Kim S. LeMessurier1,2,6, Amy R. Iverson3,6, Ti-Cheng Chang4, Maneesha Palipane1,2, Peter Vogel 5, Jason W. Rosch 3,6 & Amali E. Samarasinghe 1,2,6* Asthma is a chronic airways condition that can be exacerbated during respiratory infections. Our previous work, together with epidemiologic fndings that asthmatics were less likely to sufer from severe infuenza during the 2009 pandemic, suggest that additional complications of infuenza such as increased susceptibility to bacterial superinfection, may be mitigated in allergic hosts. To test this hypothesis, we developed a murine model of ‘triple-disease’ in which mice rendered allergic to Aspergillus fumigatus were co-infected with infuenza A virus and Streptococcus pneumoniae seven days apart. Signifcant alterations to known synergistic efects of co-infection were noted in the allergic mice including reduced morbidity and mortality, bacterial burden, maintenance of alveolar macrophages, and reduced lung infammation and damage. The lung microbiome of allergic mice difered from that of non-allergic mice during co-infection and antibiotic-induced perturbation to the microbiome rendered allergic animals susceptible to severe morbidity. Our data suggest that responses to co-infection in allergic hosts likely depends on the immune and microbiome states and that antibiotics should be used with caution in individuals with underlying chronic lung disease. Lung diseases are a leading cause of morbidity and mortality worldwide. Acute and chronic respiratory diseases, excluding infections, afect greater than 12% of the population in the United States and hundreds of millions worldwide1. -

Green Book Chapter Pneumococcal Disease

Chapter 25: Pneumococcal January 2018 25 Pneumococcal Pneumococcal meningitis NOTIFIABLE Pneumococcal The disease Pneumococcal disease is the term used to describe infections caused by the bacterium Streptococcus pneumoniae (also called pneumococcus). S. pneumoniae is an encapsulated Gram-positive coccus. The capsule is the most important virulence factor of S. pneumoniae; pneumococci that lack the capsule are normally not virulent. Over 90 different capsular types have been characterised. Prior to the routine conjugate vaccination, around 69% of invasive pneumococcal infections were caused by the ten (14, 9V, 1, 8, 23F, 4, 3, 6B, 19F, 7F) most prevalent serotypes (Trotter et al., 2010). Some serotypes of the pneumococcus may be carried in the nasopharynx without symptoms, with disease occurring in a small proportion of infected individuals. Other serotypes are rarely identified in the nasopharynx but are associated with invasive disease. The incubation period for pneumococcal disease is not clearly defined but it may be as short as one to three days. The organism may spread locally into the sinuses or middle ear cavity, causing sinusitis or otitis media. It may also affect the lungs to cause pneumonia, or cause systemic (invasive) infections including bacteraemic pneumonia, bacteraemia and meningitis. Transmission is by aerosol, droplets or direct contact with respiratory secretions of someone carrying the organism. Transmission usually requires either frequent or prolonged close contact. There is a seasonal variation in pneumococcal disease, with peak levels in the winter months. Invasive pneumococcal disease is a major cause of morbidity and mortality. It particularly affects the very young, the elderly, those with an absent or non-functioning spleen and those with other causes of impaired immunity. -

Guidance Notes on Community Acquired Pneumonia

Community-Acquired Pneumonia Introduction Community acquired pneumonia (CAP) refers to an acute infection of the lung parenchyma in a patient who has acquired the infection outside of a healthcare setting, and developed symptoms and signs in the community or within 48 hours after admission to hospitals, in the absence of recent hospitalisation. Aetiology CAP can be caused by a variety of pathogens. In the outpatient setting, the most frequently detected pathogens are Streptococcus pneumoniae, Mycoplasma pneumoniae and respiratory viruses (e.g. influenza, parainfluenza, respiratory syncytial virus). Less frequent causes include Haemophilus influenzae and Moraxella catarrhalis. Group A Streptococcus and Staphylococcus aureus may cause secondary bacterial pneumonia following influenza. A recent study on the distribution of the microbial aetiology in relation to the clinical setting and severity, among a total of 3523 adult patients with CAP, 514 (14.6 %) were outpatients. The microbial aetiology was known in 161 outpatients (31 %). Selected frequencies of pathogen are Streptococcus pneumoniae (35 %), Mycoplasma pneumoniae (17 %), H. influenzae (5%), methicillin-sensitive S. aureus (1%), respiratory viruses (9 %) and mixed aetiologies (9 %). M. catarrhalis was not detected among outpatients in this study. (1) Clinical features Common clinical features of CAP include cough, fever, pleuritic chest pain, dyspnoea and sputum production. Mucopurulent sputum production is most frequently found in association with bacterial pneumonia (e.g. Streptococcus pneumoniae), while scant or watery sputum production is more suggestive of an atypical pathogen (e.g. Mycoplasma pneumoniae). On physical examination, many are febrile, although this finding is frequently absent in older outpatients. Tachypnoea and tachycardia are also common. Chest examination reveals audible crackles in most outpatients. -

Synergism and Antagonism of Bacterial-Viral Co-Infection in the Upper Respiratory Tract

bioRxiv preprint doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/2020.11.11.378794; this version posted November 11, 2020. The copyright holder for this preprint (which was not certified by peer review) is the author/funder, who has granted bioRxiv a license to display the preprint in perpetuity. It is made available under aCC-BY-NC-ND 4.0 International license. Synergism and antagonism of bacterial-viral co-infection in the upper respiratory tract Sam Manna1,2,3, Julie McAuley3, Jonathan Jacobson1, Cattram D. Nguyen1,2, Md Ashik Ullah4, Victoria Williamson1, E. Kim Mulholland1,2,5, Odilia Wijburg3, Simon Phipps4 and Catherine Satzke1,2,3,* 1 Infection and Immunity, Murdoch Children’s Research Institute, Royal Children's Hospital, Parkville, Victoria, Australia; 2 Department of Paediatrics, The University of Melbourne, Parkville, Victoria, Australia; 3 Department of Microbiology and Immunology at the Peter Doherty Institute for Infection and Immunity, The University of Melbourne, Parkville, Victoria, Australia 4 Respiratory Immunology Laboratory, QIMR Berghofer Medical Research Institute, Herston, Queensland, Australia; 5 Department of Infectious Disease Epidemiology, London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine, London, United Kingdom *Correspondence: [email protected] Keywords: Streptococcus pneumoniae, pneumococcus, Respiratory Syncytial Virus, Pneumonia Virus of Mice, Murine Pneumonia Virus, Influenza, co-infection ABSTRACT Streptococcus pneumoniae (the pneumococcus) is a leading cause of pneumonia in children under five years old. Co-infection by pneumococci and respiratory viruses enhances disease severity. Little is known about pneumococcal co-infections with Respiratory Syncytial Virus (RSV). Here, we developed a novel infant mouse model of co-infection using Pneumonia Virus of Mice (PVM), a murine analogue of RSV, to examine the dynamics of co-infection in the upper respiratory tract, an anatomical niche that is essential for host-to-host transmission and progression to disease. -

The Drop in Reported Invasive Pneumococcal Disease Among Adults During the First COVID-19 Wave

medRxiv preprint doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/2021.06.29.21259494; this version posted July 3, 2021. The copyright holder for this preprint (which was not certified by peer review) is the author/funder, who has granted medRxiv a license to display the preprint in perpetuity. It is made available under a CC-BY-NC-ND 4.0 International license . The drop in reported invasive pneumococcal disease among adults during the first COVID-19 wave in the Netherlands explained. Kirsten Dirkx1,2, Bert Mulder1, Annelies Post1, Martijn Rutten3, Caroline Swanink4, Heiman Wertheim2, Amelieke Cremers2 1Department of Clinical Microbiology and Infectious Diseases, Canisius-Wilhelmina Ziekenhuis, Nijmegen, the Netherlands 2Department of Clinical Microbiology, Radboud Centre for Infectious Diseases, Radboudumc, Nijmegen, the Netherlands 3Department of Primary and Community Care, Radboud University Medical Centre, Nijmegen, The Netherlands 4Department of Clinical Microbiology and Immunology, Rijnstate, Arnhem, the Netherlands Abstract Streptococcus pneumoniae is the main bacterial pathogen causing respiratory infections. Since the COVID-19 pandemic emerged, less pneumococcal disease was identified by surveillance systems around the world. Measures to prevent transmission of SARS-CoV-2 also reduce transmission of pneumococci, but this would gradually lead to lower disease rates. Here, we explore additional factors that have contributed to the instant drop in pneumococcal disease cases captured in surveillance. Our observations on referral practices and other impediments to diagnostic testing indicate that residual IPD has likely occurred but remained undetected by conventional hospital- based surveillance. Depending on setting, we discuss alternative monitoring strategies that could improve sight on pneumococcal disease dynamics. Keywords: S. pneumoniae, IPD, COVID-19, surveillance, pandemic NOTE: This preprint reports new research that has not been certified by peer review and should not be used to guide clinical practice.