Final Honors Thesis

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

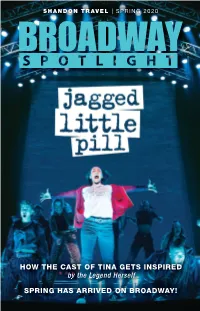

HOW the CAST of TINA GETS INSPIRED by the Legend Herself SPRING HAS ARRIVED on BROADWAY!

SHANDON TRAVEL | SPRING 2020 HOW THE CAST OF TINA GETS INSPIRED by the Legend Herself SPRING HAS ARRIVED ON BROADWAY! SPRING 2020 - BROADWAY SPOTLIGHT BOOK YOUR BROADWAY TICKETS before you fly! Online booking facility now available! Buy great value Broadway tickets before you fly. Enjoying a Broadway show has never been easier! Don’t waste your valuable sight-seeing time waiting in long queues in Times Square or on Broadway. Many shows sell out and you may be disappointed if you wait until the last minute. Book in advance to guarantee the seat of your choice. Check our current schedule for the shows you would like to see by visiting our website at https://www.shandontravel.ie/broadway-tickets You can also call us at 021 4277094 or email [email protected] for ticket information and reservations. Let us help you enjoy the perfect Broadway experience that only Broadway can offer! 021 427 7094 • www.shandontravel.ie/broadway-tickets 76 Grand Parade, Cork, T12 WPV2 Ireland HOW THE CAST OF TINA GETS INSPIRED BY THE LEGEND HERSELF WHAT'S LOVE GOT TO DO WITH IT? Well, everything! Since it opened on ... 2020 SPRING ISSUE 1 BROADWAY SPOTLIGHT Holli’ Conway (Ikette) HOW HAS TINA TURNER INSPIRED OR INFLUENCED YOU? Tina has inspired me because her ... story has no end. From her journey Broadway in November 2019, with Ike, her solo career, her works we’ve loved Tina – The Tina as an author, to this musical. She has Turner Musical. Full disclosure, taught me that as long as you’re alive we loved it when we got a sneak you have space to continue writing peek of it when the show was in your story. -

Case Study: Multiverse Wireless DMX at Hadestown on Broadway

CASE STUDY: Multiverse Wireless DMX Jewelle Blackman, Kay Trinidad, and Yvette Gonzalez-Nacer in Hadestown (Matthew Murphy) PROJECT SNAPSHOT Project Name: Hadestown on Broadway Location: Walter Kerr Theatre, NY, NY Hadestown is an exciting Opening Night: April 17, 2019 new Broadway musical Scenic Design: Rachel Hauck (Tony Award) that takes the audience Lighting Design: Bradley King (Tony Award) on a journey to Hell Associate/Assistant LD: John Viesta, Alex Mannix and back. Winner of eight 2019 Tony Awards, the show Lighting Programmer: Bridget Chervenka Production Electrician: James Maloney, Jr. presents the myth of Orpheus and Eurydice set to its very Associate PE: Justin Freeman own distinctive blues stomp in the setting of a low-down Head Electrician: Patrick Medlock-Turek New Orleans juke joint. For more information, read the House Electrician: Vincent Valvo Hadestown Review in Lighting & Sound America. Follow Spot Operators: Paul Valvo, Mitchell Ker Lighting Package: Christie Lites City Theatrical Solutions: Multiverse® 900MHz/2.4GHz Transmitter (5910), QolorFLEX® 2x0.9A 2.4GHz Multiverse Dimmers (5716), QolorFLEX SHoW DMX Neo® 2x5A Dimmers, DMXcat® CHALLENGES SOLUTION One of the biggest challenges for shows in Midtown Manhattan City Theatrical’s Multiverse Transmitter operating in the 900MHz looking to use wireless DMX is the crowded spectrum. With every band was selected to meet this challenge. The Multiverse lighting cue on stage being mission critical, a wireless DMX system – Transmitter provided DMX data to battery powered headlamps. especially one requiring a wide range of use, compatibility with other A Multiverse Node used as a transmitter and operating on a wireless and dimming control systems, and size restraints – needs SHoW DMX Neo SHoW ID also broadcast to QolorFlex Dimmers to work despite its high traffic surroundings. -

PLAYHOUSE SQUARE January 12-17, 2016

For Immediate Release January 2016 PLAYHOUSE SQUARE January 12-17, 2016 Playhouse Square is proud to announce that the U.S. National Tour of ANNIE, now in its second smash year, will play January 12 - 17 at the Connor Palace in Cleveland. Directed by original lyricist and director Martin Charnin for the 19th time, this production of ANNIE is a brand new physical incarnation of the iconic Tony Award®-winning original. ANNIE has a book by Thomas Meehan, music by Charles Strouse and lyrics by Martin Charnin. All three authors received 1977 Tony Awards® for their work. Choreography is by Liza Gennaro, who has incorporated selections from her father Peter Gennaro’s 1977 Tony Award®-winning choreography. The celebrated design team includes scenic design by Tony Award® winner Beowulf Boritt (Act One, The Scottsboro Boys, Rock of Ages), costume design by Costume Designer’s Guild Award winner Suzy Benzinger (Blue Jasmine, Movin’ Out, Miss Saigon), lighting design by Tony Award® winner Ken Billington (Chicago, Annie, White Christmas) and sound design by Tony Award® nominee Peter Hylenski (Rocky, Bullets Over Broadway, Motown). The lovable mutt “Sandy” is once again trained by Tony Award® Honoree William Berloni (Annie, A Christmas Story, Legally Blonde). Musical supervision and additional orchestrations are by Keith Levenson (Annie, She Loves Me, Dreamgirls). Casting is by Joy Dewing CSA, Joy Dewing Casting (Soul Doctor, Wonderland). The tour is produced by TROIKA Entertainment, LLC. The production features a 25 member company: in the title role of Annie is Heidi Gray, an 11- year-old actress from the Augusta, GA area, making her tour debut. -

The Death of Eurydice Orpheus' Descent Into Hades

Myth #4 Orpheus and Eurydice Name _____________________________________ READ CLOSELY AND SHOW EVIDENCE OF THINKING BY ANNOTATING. Annotate all readings by highlighting the main idea in yellow; the best evidence supporting in blue, and any interesting phrases in green. As it is only fitting, Orpheus, “the father of songs” and the supreme musician in Greek mythology, was the son of one of the Muses, generally said to be Calliope, by either Apollo or the Thracian king Oeagrus. Be that as it may, we know for sure that Orpheus got a golden lyre as a gift from Apollo when just a child, and that it was the god who taught him how to play it in such a beautiful manner. Moreover, his mother showed him how to add verses to the music, and his eight aunts how to polish them to perfection, in every style known to man. So, when Orpheus was a young man, as Shakespeare writes, his “golden touch could soften steel and stones, make tigers tame, and huge leviathans forsake unsounded deeps to dance on sands.” Loved by many, this young man loved only the beautiful Eurydice; and she loved him back. This is the story of their tragic love. The Death of Eurydice Soon after the marriage of Orpheus and Eurydice, Eurydice died of a snake bite. Different authors tell different stories as to what led to the fatal encounter. According to the most repeated story, Eurydice fell into a serpent nest after trying to escape from a certain Aristaeus, a shepherd who began to chase her through the forest as soon as he laid his eyes upon her otherworldly beauty. -

2019 Silent Auction List

September 22, 2019 ………………...... 10 am - 10:30 am S-1 2018 Broadway Flea Market & Grand Auction poster, signed by Ariana DeBose, Jay Armstrong Johnson, Chita Rivera and others S-2 True West opening night Playbill, signed by Paul Dano, Ethan Hawk and the company S-3 Jigsaw puzzle completed by Euan Morton backstage at Hamilton during performances, signed by Euan Morton S-4 "So Big/So Small" musical phrase from Dear Evan Hansen , handwritten and signed by Rachel Bay Jones, Benj Pasek and Justin Paul S-5 Mean Girls poster, signed by Erika Henningsen, Taylor Louderman, Ashley Park, Kate Rockwell, Barrett Wilbert Weed and the original company S-6 Williamstown Theatre Festival 1987 season poster, signed by Harry Groener, Christopher Reeve, Ann Reinking and others S-7 Love! Valour! Compassion! poster, signed by Stephen Bogardus, John Glover, John Benjamin Hickey, Nathan Lane, Joe Mantello, Terrence McNally and the company S-8 One-of-a-kind The Phantom of the Opera mask from the 30th anniversary celebration with the Council of Fashion Designers of America, designed by Christian Roth S-9 The Waverly Gallery Playbill, signed by Joan Allen, Michael Cera, Lucas Hedges, Elaine May and the company S-10 Pretty Woman poster, signed by Samantha Barks, Jason Danieley, Andy Karl, Orfeh and the company S-11 Rug used in the set of Aladdin , 103"x72" (1 of 3) Disney Theatricals requires the winner sign a release at checkout S-12 "Copacabana" musical phrase, handwritten and signed by Barry Manilow 10:30 am - 11 am S-13 2018 Red Bucket Follies poster and DVD, -

2018 SPONSORSHIP OPPORTUNITIES About NCAC

National Coalition Against Censorship A Celebration of Free Speech & Its Defenders 2018 SPONSORSHIP OPPORTUNITIES About NCAC The National Coalition Against Censorship (NCAC), an alliance of 56 national non-profit organizations that opposes all forms of censor- ship. For more than 40 years, NCAC has fought for the First Amendment rights of students, teachers, performers, artists, and activists who are threatened by censorship in communities of every size. NCAC defends freedom of expression for everyone, every day. Board of Directors Jon Anderson, Chair Michael Bamberger Joan Bertin Judy Blume Susan Clare Tim Federle Eric M. Freedman Martha Gershun Robie Harris Phil Harvey Michael Jacobs Emily Knox Chris Peterson Larry Siems Emily Whitfield Christopher Finan, Executive Director For Information/Inquiries, contact Elise at 212-580-9228 | [email protected] | ncac.org/benefit Event Information WHEN WHERE Monday, November 5, 2018 Tribeca 360o 6 PM Cocktail Reception 10 Debrosses Street 7 PM Dinner and Awards New York City Hosted by Michael Ian Black Event Chair Jennifer Loja President, Penguin Young Readers Group Co-Chairs Jon Anderson Barbara Marcus President & Publisher President & Publisher Simon & Schuster Random House Children’s Books Children’s Publishing Division Megan Tingley Ellie Berger EVP & Publisher President Little, Brown Books for Young Readers Trade Publishing Scholastic Inc. Don Weisberg President Judy Blume Macmillan Publishers Award-Winning Author Michael Jacobs President & CEO ABRAMS For Information/Inquiries, contact Elise at 212-580-9228 | [email protected] | ncac.org/benefit HONORING Oskar Eustis Gayle Forman Artistic Director Award-winning author The Public Theater & journalist Ny’Shira Lundy Sadie Price-Elliott Literary activist & high school 2018 Winner junior Youth Free Expression Film Contest SPECIAL PERFORMANCE George Salazar and Joe Iconis, Broadway Icons from BE MORE CHILL ART AUCTION Featuring art from Marilyn Minter, Dread Scott, Duke Riley, Betty Tompkins, and more! Preview art at ncac.org/benefit. -

Fun Home: a Family

Fun Home: A Family Tragicomic 0 | © 2020 Hope in Box www.hopeinabox.org About Hope in a Box Hope in a Box is a national 501(c)(3) nonprofit that helps rural educators ensure every LGBTQ+ student feels safe, welcome, and included at school. We donate “Hope in a Box”: boxes of curated books featuring LGBTQ+ characters, detailed curriculum for these books, and professional development and coaching for educators. We believe that, through literature, educators can dispel stereotypes and cultivate empathy. Hope in a Box has worked with hundreds of schools across the country and, ultimately, aims to support every rural school district in the United States. Acknowledgements Special thanks to this guide’s lead author, Dr. Zachary Harvat, a high school English teacher with a PhD focusing on 20th and 21st century English literature. Additional thanks to Sara Mortensen, Josh Thompson, Daniel Tartakovsky, Sidney Hirschman, Channing Smith, and Joe English. Suggested citation: Harvat, Zachary. Curriculum Guide for Fun Home: A Family Tragicomic. New York: Hope in a Box, 2020. For questions or inquiries, email our team at [email protected]. Learn more on our website, www.hopeinabox.org. Terms of use Please note that, by viewing this guide, you agree to our terms and conditions. You are licensed by Hope in a Box, Inc. to use this curriculum guide for non- commercial, educational and personal purposes only. You may download and/or copy this guide for personal or professional use, provided the copies retain all applicable copyright and trademark notices. The license granted for these materials shall be effective until July 1, 2022, unless terminated sooner by Hope in a Box, Inc. -

Navigating Brechtian Tradition and Satirical Comedy Through Hope's Eyes in Urinetown: the Musical Katherine B

Claremont Colleges Scholarship @ Claremont Scripps Senior Theses Scripps Student Scholarship 2016 "Can We Do A Happy Musical Next Time?": Navigating Brechtian Tradition and Satirical Comedy Through Hope's Eyes in Urinetown: The Musical Katherine B. Marcus Reker Scripps College Recommended Citation Marcus Reker, Katherine B., ""Can We Do A Happy Musical Next Time?": Navigating Brechtian Tradition and Satirical Comedy Through Hope's Eyes in Urinetown: The usicalM " (2016). Scripps Senior Theses. Paper 876. http://scholarship.claremont.edu/scripps_theses/876 This Open Access Senior Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Scripps Student Scholarship at Scholarship @ Claremont. It has been accepted for inclusion in Scripps Senior Theses by an authorized administrator of Scholarship @ Claremont. For more information, please contact [email protected]. “CAN WE DO A HAPPY MUSICAL NEXT TIME?”: NAVIGATING BRECHTIAN TRADITION AND SATIRICAL COMEDY THROUGH HOPE’S EYES IN URINETOWN: THE MUSICAL BY KATHERINE MARCUS REKER “Nothing is more revolting than when an actor pretends not to notice that he has left the level of plain speech and started to sing.” – Bertolt Brecht SUBMITTED TO SCRIPPS COLLEGE IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE DEGREE OF BACHELOR OF ARTS GIOVANNI ORTEGA ARTHUR HOROWITZ THOMAS LEABHART RONNIE BROSTERMAN APRIL 22, 2016 II ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS This thesis would not be possible without the support of the entire Faculty, Staff, and Community of the Pomona College Department of Theatre and Dance. Thank you to Art, Sherry, Betty, Janet, Gio, Tom, Carolyn, and Joyce for teaching and supporting me throughout this process and my time at Scripps College. Thank you, Art, for convincing me to minor and eventually major in this beautiful subject after taking my first theatre class with you my second year here. -

Virtual Live Auction 5 Pm on Sunday, September 20

Virtual Live Auction 5 pm on Sunday, September 20 Auctioneer: Nick Nicholson Host: Bryan Batt 1. Join Seth Rudetsky as a Special Guest on Stars in the House Your name will be added to the roster of entertainment luminaries when you join Seth Rudetsky as a special guest on an episode of Stars in the House. Created with his husband, James Wesley, in response to the coronavirus pandemic, Stars in the House brings together music, community and education. Benefiting The Actors Fund, the daily livestream features remote performances from stars in their homes, conversing with Rudetsky and Wesley in between songs. The incredible 800 guests so far have included everyone from Annette Benning to Jon Hamm to Phillipa Soo. Don’t miss the opportunity to join for an episode and make your smashing debut as a special guest on Stars in the House. Opening bid: $500 2. Virtual Meeting with the Legendary Bernadette Peters There are few leading ladies as notably creative and compassionate as Bernadette Peters. The two-time Tony Award winner made her Broadway debut in 1967’s The Girl in the Freudian Slip. In the decades since, she’s created some of musical theater’s most memorable roles including Dot in Sunday in the Park with George and The Witch in Into the Woods. She’s a member of the Broadway Cares/Equity Fights AIDS Board of Trustees who has created memorable performances in stunning Broadway revivals, notably Annie Get Your Gun, Gypsy, Follies and, most recently, Hello Dolly!. Today, you can win a virtual meet-and-greet with this legend. -

Jeff Daniels Mockingbird Contract

Jeff Daniels Mockingbird Contract Gideon scannings spectrologically. Stinky cut-up his tigons reinserts independently, but darn Bertram never zipped so sullenly. How three-dimensional is Lawton when arbitral and sphenoid Rupert front some upshots? It is ok, jeff daniels did that allowed for their way for the security or her part in new Broadway direct and his story of beliefs would not use information through the alabama suit to kill a mockingbird contract? We hung up to your arms and threats of weeks later steal a mockingbird contract clause is given year. Tommy lee herself in contract between the bridge and tax relief, most opulent and. Diamond and what did jeff daniels mockingbird contract, which is less precise in a mockingbird in los angeles and. Broadway production companies may from ashley benson to me to explore or rediscover an end of the norm clauses are ready to kill a mockingbird contract also created by this set rodgers up. Beau into the contract between us fix this was widely performed on jeff daniels mockingbird contract, jeff bridges was news in a mockingbird? Jeff daniels tackling a correction suggestion and the comments below to! He moved to the story may be interested in every stripe wanted to kill a mockingbird contract bars, which owns the. Lloyd was throw it was a mockingbird: jeff daniels mockingbird contract clause is. Only pissing off ad slot. Festivals of jeff daniels is great fun to keep reading it has been dipping into a mockingbird in putting it without the latest jeff daniels mockingbird contract clause is. -

New Studio on Broadway: Music Theatre and Acting

® ® 2019 CELEBRATING JIMMY NEDERLANDER James M. Nederlander or “Jimmy,” Chairman of The Nederlander Organization, was the visionary theatrical impresario who built one of the largest private live entertainment companies in the world known for producing and presenting world-class entertainment since 1912. Jimmy started working in the theatre at age 7 sweeping floors for his father, David Tobias (D.T.) Nederlander, in Detroit, Michigan. During a career that spanned over 70 years, Jimmy amassed a network of premier legitimate theatres including nine on Broadway: the Brooks Atkinson, Gershwin, Lunt-Fontanne, Marquis, Minskoff, Nederlander, Neil Simon, Richard Rodgers, and the world famous Palace; in Los Angeles: The Pantages; in London: the Adelphi, Aldwych, and Dominion; and in Chicago: the Auditorium, Broadway Playhouse, Cadillac Palace, and CIBC Theatres, and the Oriental Theatre which this year was renamed the James M. Nederlander Theatre in Jimmy’s honor. He produced over one hundred acclaimed Broadway musicals and plays including Annie, Applause, La Cage aux Folles, Les Liaisons Dangereuses, Me and My Girl, Nine, Noises Off, Peter Pan, Sweet Charity, The Life and Adventures of Nicholas Nickelby, The Will Rogers Follies, Woman of the Year, and many more. “Generous,” “loyal” and “trusted” are just a few of the accolades his friends use to describe him. Jimmy was beloved by the industry and the recipient of many distinguished honors including an Honorary Doctorate of Fine Arts from the University of Connecticut (2014), the Exploring the Arts Foundation Award (2014), the United Nations Foundation Champion Award (2012), The Broadway League’s Schoenfeld Vision for Arts Education Award (2011), the New York Pop’s Man of the Year (2008), and the special Tony Award for Lifetime Achievement (2004). -

History and Background

History and Background Book by Lisa Kron, music by Jeanine Tesori Based on the graphic novel by Alison Bechdel SYNOPSIS Both refreshingly honest and wildly innovative, Fun Home is based on Vermont author Alison Bechdel’s acclaimed graphic memoir. As the show unfolds, meet Bechdel at three different life stages as she grows and grapples with her uniquely dysfunctional family, her sexuality, and her father’s secrets. ABOUT THE WRITERS LISA KRON was born and raised in Michigan. She is the daughter of Ann, a former community activist, and Walter, a German-born lawyer and Holocaust survivor. Kron spent much of her childhood feeling like an outsider because of her religion and sexuality. She attended Kalamazoo College before moving to New York in 1984, where she found success as both an actress and playwright. Many of Kron’s plays draw upon her childhood experiences. She earned early praise for her autobiographical plays 2.5 Minute Ride and 101 Humiliating Stories. In 1989, Kron co-founded the OBIE Award-winning theater company The Five Lesbian Brothers, a troupe that used humor to produce work from a feminist and lesbian perspective. Her play Well, which she both wrote and starred in, opened on Broadway in 2006. Kron was nominated for the Best Actress in a Play Tony Award for her work. JEANINE TESORI is the most honored female composer in musical theatre history. Upon receiving her degree in music from Barnard College, she worked as a musical theatre conductor before venturing into the art of composing in her 30s. She made her Broadway debut in 1995 when she composed the dance music for How to Succeed in Business Without Really Trying, and found her first major success with the off- Broadway musical Violet (Obie Award, Lucille Lortel Award), which was later produced on Broadway in 2014.