Npr 4.3: Social and Environmental Aspects Of

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Educated Youth Should Go to the Rural Areas: a Tale of Education, Employment and Social Values*

Educated Youth Should Go to the Rural Areas: A Tale of Education, Employment and Social Values* Yang You† Harvard University This draft: July 2018 Abstract I use a quasi-random urban-dweller allocation in rural areas during Mao’s Mass Rustication Movement to identify human capital externalities in education, employment, and social values. First, rural residents acquired an additional 0.1-0.2 years of education from a 1% increase in the density of sent-down youth measured by the number of sent-down youth in 1969 over the population size in 1982. Second, as economic outcomes, people educated during the rustication period suffered from less non-agricultural employment in 1990. Conversely, in 2000, they enjoyed increased hiring in all non-agricultural occupations and lower unemployment. Third, sent-down youth changed the social values of rural residents who reported higher levels of trust, enhanced subjective well-being, altered trust from traditional Chinese medicine to Western medicine, and shifted job attitudes from objective cognitive assessments to affective job satisfaction. To explore the mechanism, I document that sent-down youth served as rural teachers with two new county-level datasets. Keywords: Human Capital Externality, Sent-down Youth, Rural Educational Development, Employment Dynamics, Social Values, Culture JEL: A13, N95, O15, I31, I25, I26 * This paper was previously titled and circulated, “Does living near urban dwellers make you smarter” in 2017 and “The golden era of Chinese rural education: evidence from Mao’s Mass Rustication Movement 1968-1980” in 2015. I am grateful to Richard Freeman, Edward Glaeser, Claudia Goldin, Wei Huang, Lawrence Katz, Lingsheng Meng, Nathan Nunn, Min Ouyang, Andrei Shleifer, and participants at the Harvard Economic History Lunch Seminar, Harvard Development Economics Lunch Seminar, and Harvard China Economy Seminar, for their helpful comments. -

Bubonic Plague

THE BLACK DEATH, OR BUBONIC PLAGUE “I know histhry isn’t thrue, Hinnissy, because it ain’t like what I see ivry day in Halsted Street. If any wan comes along with a histhry iv Greece or Rome that’ll show me th’ people fightin’, gettin’ dhrunk, makin’ love, gettin’ married, owin’ th’ grocery man an’ bein’ without hard coal, I’ll believe they was a Greece or Rome, but not befur.” — Dunne, Finley Peter, OBSERVATIONS BY MR. DOOLEY, New York, 1902 An infectious virus, according to Peter Medewar, is a piece of nucleic acid surrounded by bad news. This is what the virus carried by the female Culicidae Aëdes aegypti mosquito, causing what was known as black vomit, the American plague, yellow jacket, bronze John, dock fever, stranger’s fever (now standardized as the “yellow fever”) actually looks like, Disney-colorized for your entertainment: And this is what the infectious virus causing Rubeola, the incredibly deadly and devastating German measles, looks like, likewise Disney-colorized for your entertainment: Most infectious viruses have fewer than 10 genes, although the virus that caused the small pox was the biggie exception, having from 200 to 400 genes: HDT WHAT? INDEX BUBONIC PLAGUE THE BLACK DEATH Then, of course, there is the influenza, which exists in various forms as different sorts of this virus mutate and migrate from time to time from other species into humans — beginning with an “A” variety that made the leap from wild ducks to domesticated ducks circa 2500 BCE. (And then there is our little friend the coma bacillus Vibrio cholerae, that occasionally makes its way from our privies into our water supplies and causes us to come down with the “Asiatic cholera.”) On the other hand, the scarlet fever, also referred to as Scarlatina, is an infection caused not by a virus but by one or another of the hemoglobin-liberating bacteria, typically Streptococcus pyogenes. -

Research on Employment Difficulties and the Reasons of Typical

2017 3rd International Conference on Education and Social Development (ICESD 2017) ISBN: 978-1-60595-444-8 Research on Employment Difficulties and the Reasons of Typical Resource-Exhausted Cities in Heilongjiang Province during the Economic Transition Wei-Wei KONG1,a,* 1School of Public Finance and Administration, Harbin University of Commerce, Harbin, China [email protected] *Corresponding author Keywords: Typical Resource-Exhausted Cities, Economic Transition, Employment. Abstract. The highly correlation between the development and resources incurs the serious problems of employment during the economic transition, such as greater re-employment population, lower elasticity of employment, greater unemployed workers in coal industry. These problems not only hinder the social stability, but also slow the economic transition and industries updating process. We hope to push forward the economic transition of resource-based cities and therefore solve the employment problems through the following measures: developing specific modern agriculture and modern service industry, encouraging and supporting entrepreneurships, implementing re-employment trainings, strengthening the public services systems for SMEs etc. Background According to the latest statistics from the State Council for 2013, there exists 239 resource-based cities in China, including 31 growing resource-based cities, 141 mature, and 67 exhausted. In the process of economic reform, resource-based cities face a series of development challenges. In December 2007, the State Council issued the Opinions on Promoting the Sustainable Development of Resource-Based Cities. The National Development and Reform Commission identified 44 resource-exhausted cities from March 2008 to March 2009, supporting them with capital, financial policy and financial transfer payment funds. In the year of 2011, the National Twelfth Five-Year Plan proposed to promote the transformation and development of resource-exhausted area. -

CHEMICAL WEAPONS CONVENTION BULLETIN News, Background and Comment on Chemical and Biological Warfare Issues

CHEMICAL WEAPONS CONVENTION BULLETIN News, Background and Comment on Chemical and Biological Warfare Issues ISSUE NO. 30 DECEMBER 1995 Quarterly Journal of the Harvard Sussex Program on CBW Armament and Arms Limitation OVER THE IMPASSE The dispute with the White House in which the Chair- Third, the Preparatory Commission needs to reach final man of the US Senate Foreign Relations Committee decisions soon regarding management and technical mat- blocked action on the Chemical Weapons Convention and ters that require decision well before entry into force. Such other Executive Branch requests for most of this year has long lead-time matters include approval of the design and been resolved. funding of the Information Management System which On the floor of the Senate early this month the Foreign must be up and running before declarations containing con- Relations Committee Chairman, Senator Jesse Helms, an- fidential information can be processed by the Technical nounced that the Committee will resume hearings on the Secretariat; agreement on declaration-related and industry- Convention in February and that the Convention will be related issues to allow States Parties sufficient time to pre- moved out of committee no later than the end of April. As pare their declarations and facility agreements; and part of the agreement, the Senate Majority Leader, Senator agreement on conditions of service for OPCW personnel so Robert Dole, who controls floor scheduling, pledged to that recruitment of inspectors and others can proceed place the Convention before the full Senate within a “rea- smoothly. sonable time period” after it leaves the Committee. This means that the Senate could vote on the Convention in May. -

China Russia

1 1 1 1 Acheng 3 Lesozavodsk 3 4 4 0 Didao Jixi 5 0 5 Shuangcheng Shangzhi Link? ou ? ? ? ? Hengshan ? 5 SEA OF 5 4 4 Yushu Wuchang OKHOTSK Dehui Mudanjiang Shulan Dalnegorsk Nongan Hailin Jiutai Jishu CHINA Kavalerovo Jilin Jiaohe Changchun RUSSIA Dunhua Uglekamensk HOKKAIDOO Panshi Huadian Tumen Partizansk Sapporo Hunchun Vladivostok Liaoyuan Chaoyang Longjing Yanji Nahodka Meihekou Helong Hunjiang Najin Badaojiang Tong Hua Hyesan Kanggye Aomori Kimchaek AOMORI ? ? 0 AKITA 0 4 DEMOCRATIC PEOPLE'S 4 REPUBLIC OF KOREA Akita Morioka IWATE SEA O F Pyongyang GULF OF KOREA JAPAN Nampo YAMAJGATAA PAN Yamagata MIYAGI Sendai Haeju Niigata Euijeongbu Chuncheon Bucheon Seoul NIIGATA Weonju Incheon Anyang ISIKAWA ChechonREPUBLIC OF HUKUSIMA Suweon KOREA TOTIGI Cheonan Chungju Toyama Cheongju Kanazawa GUNMA IBARAKI TOYAMA PACIFIC OCEAN Nagano Mito Andong Maebashi Daejeon Fukui NAGANO Kunsan Daegu Pohang HUKUI SAITAMA Taegu YAMANASI TOOKYOO YELLOW Ulsan Tottori GIFU Tokyo Matsue Gifu Kofu Chiba SEA TOTTORI Kawasaki KANAGAWA Kwangju Masan KYOOTO Yokohama Pusan SIMANE Nagoya KANAGAWA TIBA ? HYOOGO Kyoto SIGA SIZUOKA ? 5 Suncheon Chinhae 5 3 Otsu AITI 3 OKAYAMA Kobe Nara Shizuoka Yeosu HIROSIMA Okayama Tsu KAGAWA HYOOGO Hiroshima OOSAKA Osaka MIE YAMAGUTI OOSAKA Yamaguchi Takamatsu WAKAYAMA NARA JAPAN Tokushima Wakayama TOKUSIMA Matsuyama National Capital Fukuoka HUKUOKA WAKAYAMA Jeju EHIME Provincial Capital Cheju Oita Kochi SAGA KOOTI City, town EAST CHINA Saga OOITA Major Airport SEA NAGASAKI Kumamoto Roads Nagasaki KUMAMOTO Railroad Lake MIYAZAKI River, lake JAPAN KAGOSIMA Miyazaki International Boundary Provincial Boundary Kagoshima 0 12.5 25 50 75 100 Kilometers Miles 0 10 20 40 60 80 ? ? ? ? 0 5 0 5 3 3 4 4 1 1 1 1 The boundaries and names show n and t he designations us ed on this map do not imply of ficial endors ement or acceptance by the United N at ions. -

Tsetusuo Wakabayashi, Revealed

Tsetusuo Wakabayashi, Revealed By Dwight R. Rider Edited by Eric DeLaBarre Preface Most great works of art begin with an objective in mind; this is not one of them. What follows in the pages below had its genesis in a research effort to determine what, if anything the Japanese General Staff knew of the Manhattan Project and the threat of atomic weapons, in the years before the detonation of an atomic bomb over Hiroshima in August 1945. That project drew out of an intense research effort into Japan’s weapons of mass destruction programs stretching back more than two decades; a project that remains on-going. Unlike a work of art, this paper is actually the result of an epiphany; a sudden realization that allows a problem, in this case the Japanese atomic energy and weapons program of World War II, to be understood from a different perspective. There is nothing in this paper that is not readily accessible to the general public; no access to secret documents, unreported interviews or hidden diaries only recently discovered. The information used in this paper has been, for the most part, available to researchers for nearly 30 years but only rarely reviewed. The paper that follows is simply a narrative of a realization drawn from intense research into the subject. The discoveries revealed herein are the consequence of a closer reading of that information. Other papers will follow. In October of 1946, a young journalist only recently discharged from the US Army in the drawdown following World War II, wrote an article for the Atlanta Constitution, the premier newspaper of the American south. -

Planning and Brand Communication for Ice-Snow Sports Tourism Products in the Arctic Village of Mohe County

CONVERTER MAGAZINE Volume 2021, No. 5 Planning and Brand Communication for Ice-snow Sports Tourism Products in the Arctic Village of Mohe County Wei Gao, Xiaoguo Chang Harbin Finance University, Harbin, Heilongjiang, China Abstract Locating in the northernmost region of China, the Arctic Village of Mohe County is enlisted as one of the most charming tourist attractions of China for the unique resources and landscapes, such as “northernmost location”, magical astronomical phenomena and arctic ice-snow. However, it failed to explore domestic and foreign markets yet due to the poor promotion of government, thus resulting in the low consumer brand recognition. Combining with existing tourism resources in the Arctic Village, this study proposed an appropriate product planning based on the national promotion of “ice-snow tourism”. Meanwhile, great efforts were made to the propagation and publicity of the brand to improve brand influence of the Arctic Village. The ice-snow resources in surrounding region were integrated to promote the tourism development in the whole Heilongjiang Province. Keywords:Arctic Village, ice-snow tourism, product planning, brand communication I.Overview of related theories 1.1Elaboration of Concept of Ice-Snow Sports Tourism Currently, no definition on the concept of ice-snow sports tourism has been proposed yet. The foreign scholar Hall proposed in a relevant study in 1992 that “sports tourism shall be a non-commercial tourism activity that participates or watches sports activities, but is beyond the daily life range.” Li Guang and Li Yanling, two Chinese scholars, declared that “ice-snow tourism refers to various athletic activities based on ice and snow resources and the sum of tourism destinations, tourism society and tourism enterprises.” Among most opinions of Chinese and foreign scholars, ice-snow sports tourism is a branch of sports tourism and it has characteristics of both sports tourism and ice-snow tourism. -

Spatiotemporal Changes of Reference Evapotranspiration in the Highest-Latitude Region of China

Article Spatiotemporal Changes of Reference Evapotranspiration in the Highest-Latitude Region of China Peng Qi 1,2, Guangxin Zhang 1,*, Y. Jun Xu 3, Yanfeng Wu 1,2 and Zongting Gao 4 1 Key Laboratory of Wetland Ecology and Environment, Northeast Institute of Geography and Agroecology, Chinese Academy of Sciences, No. 4888, Shengbei Street, Changchun 130102, China; [email protected] (P.Q.); [email protected] (Y.W.) 2 University of the Chinese Academy of Sciences, Beijing 100049, China 3 School of Renewable Natural Resources, Louisiana State University Agricultural Center, Baton Rouge, LA 70803, USA; [email protected] 4 Institute of Meteorological Sciences of Jilin Province, and Laboratory of Research for Middle-High Latitude Circulation and East Asian Monsoon, and Jilin Province Key Laboratory for Changbai Mountain Meteorology and Climate Change, Changchun 130062, China; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +86-431-8554-2210; Fax: +86-431-8554-2298 Received: 2 June 2017; Accepted: 4 July 2017; Published: 5 July 2017 Abstract: Reference evapotranspiration (ET0) is often used to make management decisions for crop irrigation scheduling and production. In this study, the spatial and temporal trends of ET0 in China’s most northern province as well as the country’s largest agricultural region were analyzed for the period from 1964 to 2013. ET0 was calculated with the Penman-Monteith of Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations irrigation and drainage paper NO.56 (FAO-56) using climatic data collected from 27 stations. Inverse distance weighting (IDW) was used for the spatial interpolation of the estimated ET0. A Modified Mann–Kendall test (MMK) was applied to test the spatiotemporal trends of ET0, while Pearson’s correlation coefficient and cross-wavelet analysis were employed to assess the factors affecting the spatiotemporal variability at different elevations. -

Characteristics of Spatial Connection Based on Intercity Passenger Traffic Flow in Harbin- Changchun Urban Agglomeration, China Research Paper

Guo, R.; Wu, T.; Wu, X.C. Characteristics of Spatial Connection Based on Intercity Passenger Traffic Flow in Harbin- Changchun Urban Agglomeration, China Research Paper Characteristics of Spatial Connection Based on Intercity Passenger Traffic Flow in Harbin-Changchun Urban Agglomeration, China Rong Guo, School of Architecture,Harbin Institute of Technology,Key Laboratory of Cold Region Urban and Rural Human Settlement Environment Science and Technology,Ministry of Industry and Information Technology,Harbin 150006,China Tong Wu, School of Architecture,Harbin Institute of Technology,Key Laboratory of Cold Region Urban and Rural Human Settlement Environment Science and Technology,Ministry of Industry and Information Technology,Harbin 150006,China Xiaochen Wu, School of Architecture,Harbin Institute of Technology,Key Laboratory of Cold Region Urban and Rural Human Settlement Environment Science and Technology,Ministry of Industry and Information Technology,Harbin 150006,China Abstract With the continuous improvement of transportation facilities and information networks, the obstruction of distance in geographic space has gradually weakened, and the hotspots of urban geography research have gradually changed from the previous city hierarchy to the characteristics of urban connections and networks. As the main carrier and manifestation of elements, mobility such as people and material, traffic flow is of great significance for understanding the characteristics of spatial connection. In this paper, Harbin-Changchun agglomeration proposed by China's New Urbanization Plan (2014-2020) is taken as a research object. With the data of intercity passenger traffic flow including highway and railway passenger trips between 73 county-level spatial units in the research area, a traffic flow model is constructed to measure the intensity of spatial connection. -

CWCB 29 Page 2 September 1995 the Soviet Union Effectively Stopped in 1985

CHEMICAL WEAPONS CONVENTION BULLETIN News, Background and Comment on Chemical and Biological Warfare Issues ISSUE NO. 29 SEPTEMBER 1995 Quarterly Journal of the Harvard Sussex Program on CBW Armament and Arms Limitation DEFINING CHEMICAL WEAPONS THE WAY THE TREATY DOES Harmonizing the ways in which states parties implement nor such substances as the nerve gas known as Agent GP, the Chemical Weapons Convention domestically is as least means only that these chemicals have not been singled out as important as properly creating the organization in the for routine verification measures. Their omission from the Hague that will operate the treaty internationally. If states Schedules certainly does not mean that the military may use parties implement the Convention differently in certain es- them as weapons or that the domestic penal legislation re- sential respects, there will be no ‘level playing field’ for sci- quired by Article VII of the Convention should be without entific, industrial and commercial enterprise in the diverse application to their acquisition by terrorists. activities upon which the Convention impinges, nor will the The remedy, of course, is for states to write their domes- Convention achieve its potential as a powerful instrument tic implementing legislation so as to incorporate the Gen- against chemical warfare and chemical terrorism. eral Purpose Criterion, either explicitly or by reference to Of all the possible divergences in national implementa- the text of Article II of the Convention. That the draft leg- tion, the most elementary — and the one that now threatens islation now working its way through the legislative pro- to develop — is divergence regarding the very definition of cesses of some states fails to do this must in part reflect the ‘chemical weapons’ to which the provisions of the Conven- failure of the Preparatory Commission to provide guidance tion apply. -

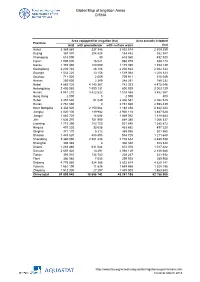

Global Map of Irrigation Areas CHINA

Global Map of Irrigation Areas CHINA Area equipped for irrigation (ha) Area actually irrigated Province total with groundwater with surface water (ha) Anhui 3 369 860 337 346 3 032 514 2 309 259 Beijing 367 870 204 428 163 442 352 387 Chongqing 618 090 30 618 060 432 520 Fujian 1 005 000 16 021 988 979 938 174 Gansu 1 355 480 180 090 1 175 390 1 153 139 Guangdong 2 230 740 28 106 2 202 634 2 042 344 Guangxi 1 532 220 13 156 1 519 064 1 208 323 Guizhou 711 920 2 009 709 911 515 049 Hainan 250 600 2 349 248 251 189 232 Hebei 4 885 720 4 143 367 742 353 4 475 046 Heilongjiang 2 400 060 1 599 131 800 929 2 003 129 Henan 4 941 210 3 422 622 1 518 588 3 862 567 Hong Kong 2 000 0 2 000 800 Hubei 2 457 630 51 049 2 406 581 2 082 525 Hunan 2 761 660 0 2 761 660 2 598 439 Inner Mongolia 3 332 520 2 150 064 1 182 456 2 842 223 Jiangsu 4 020 100 119 982 3 900 118 3 487 628 Jiangxi 1 883 720 14 688 1 869 032 1 818 684 Jilin 1 636 370 751 990 884 380 1 066 337 Liaoning 1 715 390 783 750 931 640 1 385 872 Ningxia 497 220 33 538 463 682 497 220 Qinghai 371 170 5 212 365 958 301 560 Shaanxi 1 443 620 488 895 954 725 1 211 648 Shandong 5 360 090 2 581 448 2 778 642 4 485 538 Shanghai 308 340 0 308 340 308 340 Shanxi 1 283 460 611 084 672 376 1 017 422 Sichuan 2 607 420 13 291 2 594 129 2 140 680 Tianjin 393 010 134 743 258 267 321 932 Tibet 306 980 7 055 299 925 289 908 Xinjiang 4 776 980 924 366 3 852 614 4 629 141 Yunnan 1 561 190 11 635 1 549 555 1 328 186 Zhejiang 1 512 300 27 297 1 485 003 1 463 653 China total 61 899 940 18 658 742 43 241 198 52 -

Heilongjiang Road Development II Project (Yichun-Nenjiang)

Technical Assistance Consultant’s Report Project Number: TA 7117 – PRC October 2009 People’s Republic of China: Heilongjiang Road Development II Project (Yichun-Nenjiang) FINAL REPORT (Volume II of IV) Submitted by: H & J, INC. Beijing International Center, Tower 3, Suite 1707, Beijing 100026 US Headquarters: 6265 Sheridan Drive, Suite 212, Buffalo, NY 14221 In association with WINLOT No 11 An Wai Avenue, Huafu Garden B-503, Beijing 100011 This consultant’s report does not necessarily reflect the views of ADB or the Government concerned, ADB and the Government cannot be held liable for its contents. All views expressed herein may not be incorporated into the proposed project’s design. Asian Development Bank Heilongjiang Road Development II (TA 7117 – PRC) Final Report Supplementary Appendix A Financial Analysis and Projections_SF1 S App A - 1 Heilongjiang Road Development II (TA 7117 – PRC) Final Report SUPPLEMENTARY APPENDIX SF1 FINANCIAL ANALYSIS AND PROJECTIONS A. Introduction 1. Financial projections and analysis have been prepared in accordance with the 2005 edition of the Guidelines for the Financial Governance and Management of Investment Projects Financed by the Asian Development Bank. The Guidelines cover both revenue earning and non revenue earning projects. Project roads include expressways, Class I and Class II roads. All will be built by the Heilongjiang Provincial Communications Department (HPCD). When the project started it was assumed that all project roads would be revenue earning. It was then discovered that national guidance was that Class 2 roads should be toll free. The ADB agreed that the DFR should concentrate on the revenue earning Expressway and Class I roads, 2.