9,10,11 (In Part), 15 and 16 of the Maps of the Geological Survey Of

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

13Th November 2016: Thirty-Third Sunday in Ordinary Time (Cycle C) Parish Office: Mon to Fri

St. Mary of the Visitation Parish, Killybegs Sunday 13th November 2016: Thirty-Third Sunday in Ordinary Time (Cycle C) Parish Office: Mon to Fri. 9.15am to 2.45pm. Tel: 074 9731013 Weekday Readings: Thirty-Third Week in Ordinary Time (Cycle 2) Parish Secretary: Ann O’Donnell Saturday 12th November: 07.00pm - Brendan O’Keeney (3rd Anniversary) Email: [email protected] Website: killybegsparish.com Stephen Murdiff (9th Anniversary) Parish Priest: Fr. Colm Ó Gallchóir : Tel: 074 9731030 Brendan Connaghan (Anniversary) Masses and Services: Live streaming on www.mcnmedia.tv Maureen McCallig (Anniversary) Special Intention Stained Glass Window Installation To put the world in order, we must first put Sunday 13th November: 09.00am - Michael Cunningham, Island (Anniversary) A delightful three-panel Stained Glass Window the nation in order; to put the nation in 11.00am - Paul Gallagher (Anniversary) (boxed & lit), entitled ‘God the Father’, will be order, we must first put the family in order; Monday 14th November: 10.00am - Special Intention installed above St Catherine’s Altar and unveiled at to put the family in order, we must first Tuesday 15th November: 10.00am - Willie Kerrigan (2nd Anniversary) a Mass celebrating the Feast of St Catherine of cultivate our personal life; we must first set Thursday 17th November: 10.00am - Special Intention Alexandria on Friday, 25th November, 7.00pm. our hearts right. Confucius Friday 18th November: 10.00am - Matthew Cunningham (Anniversary) All are welcome. Saturday 19th November: 11.00am - Pat Cunningham R.I.P. (Month’s Mind Mass) The window is signed ‘Harry Clarke Stain Glass Enrolment of Confirmation Candidates 07.00pm - Kathleen Cannon R.I.P. -

Donegal Winter Climbing

1 A climbers guide to Donegal Winter Climbing By Iain Miller www.uniqueascent.ie 2 Crag Index Muckish Mountain 4 Mac Uchta 8 Errigal 10 Maumlack 13 Poison Glen 15 Slieve Snaght 17 Horseshoe Corrie (Lough Barra) 19 Bluestacks (N) 22 Bluestacks (S) 22 www.uniqueascent.ie 3 Winter Climbing in Donegal. Winter climbing in the County of Donegal in the North West of Ireland is quite simply outstanding, alas it has a very fleeting window of opportunity. Due to it’s coastal position and relatively low lying mountains good winter conditions in Donegal are a rare commodity indeed. Usually temperatures have to be below 0 for 5 days consecutively, and down to -5 at night, and an ill timed dump of snow can spoil it all. To take advantage of these fleeting conditions you have to drop everything, and brave the inevitably appalling road conditions to get there, for be assured, it won’t last! When Donegal does come into prime Winter condition the crux of your days climbing will without a doubt be travelling by road throughout the county. In this guide I have tried to only use National primary and secondary roads as a means to travel and access. There are of course many regional and third class roads which provide much closer access to the mountains but under winter conditions these can very quickly become unpassable. The first recorded winter climbing I am aware of, was done in the Horsehoe Corrie in the early seventies and since then barely a couple of new routes have been logged anywhere in Donegal each decade since that! It was the winter of 2009/2010 that one of the coldest and longest winters in recorded history occurred with over 6 weeks of minus temperatures and snowdrifts of up to 12m in the Donegal uplands. -

Autumn Gathering 2017 Hosted by Crannagh Ramblers Donegal Co

Autumn Gathering 2017 Hosted by Crannagh Ramblers Donegal Co Co Hills & Trails Walking Club North West Mountaineering Club Individual Members Individual Members Friday October 13th – Sunday October 15th Organising Committee Helen Donoghue, Seamus Doohan, John Grant, Rosemary Mc Clafferty, Catherine Mc Loughlin, Norman Miller, Diarmuid Ó Donnabháin, Mary O Hara. Crannagh Ramblers The Crannagh Ramblers, 20 Years a-Growing....Fiche Bliain ag Fas The Crannagh Ramblers's inaugural walk took place on Sunday 15th June 1997. The late John Doherty, the club's founder, led the walk of 12 members on Mamore Hill, Urris. 3 of those 12 founding members are still regular walkers with the Ramblers! Since then the club has grown to 38 members. Based in Inishowen the group got its name from the Crana river on which the town of Buncrana is built. The Crannagh Ramblers is a Cross-Border club with many of its members from Derry. The club is an active hillwalking group which meets regularly. Memorable club holidays include trips to Austria and Slovenia. Our annual holidays have brought us to the Mourne Mountains, Slieve League and the Wicklow Hills. On our 20th anniversary we reminisce on the very many happy occasions we have enjoyed and the new friendships we have made. We remember in particular our founder and leader, the late John Doherty. The club has erected a plaque in his memory on Mamore hill, the hill he chose to launch the club. We are delighted that our club has grown over the years and is still very much a lively, vibrant club. -

Glaschú Go Tír Chonaill Glasgow to Donegal BOOKING IS ESSENTIAL

Glaschú go Tír Chonaill Glasgow to Donegal BOOKING IS ESSENTIAL This service operates all year round. 4 days a week, Monday, Wednesday, Friday and Saturday during peak times and 2 days a week, Wednesday and Saturday off peak. Times change occasionally so please call for up to date departure times. Town Stops Depart Glasgow Buchanan Street Bus Station @ Stand 55 7.00AM Glasgow Bedford St/Bedford Lane, Gorballs (near the bingo hall) 7.30AM Glasgow Health Centre, Caulder St 7.35AM Glasgow James Tassey Pub, Shawlands 7.40AM Glasgow Former site of the Tinto firs 7.45AM Glasgow Eastwood Toll 7.50AM Kilmarnock Balbirs Indian Resturant on M77 8.10AM Symington Balbirs Indian Resturant on M77 8.10AM Ayr Roundabout on A77 8.20AM Maybole Public Toilets 8.30AM Girvan Please Call 8.50AM Cairnryan P&O Boat Terminal 9.30AM Arrive Arrive Arrive Larne Bus Park @ P&O Boat Terminal 12.30AM Toome Public Toilets 1.10PM Casteldawson Roundabout 1.20PM Dungiven Bus Stop @ Public Tiolets 1.35PM Foreglen O Neills Filling Station 1.45PM Derry Altnagalvin / Bus Station / Pennyburn Chapel 2.00PM Strabane Lay by @ The Tinney's 2.30PM Lifford Bus Stop @ Customs 2.40PM Clady Local Drop available 2.50PM Castlefin Local Drop available 3.00PM Killygordan Local Drop available 3.10PM Bridgend Doherty’s Cafe 2.20PM Letterkenny Bus Stop @ Michael Murphy Sports and Mr Chippy 2.45PM Ramelton Local Drop off available 3.10PM Milford Garda Barracks 3.20PM Rathmullen Pier Hotel 3.30PM Kerrykeel Garda Station 3.30PM Carrigart Main Street 3.40PM Downings Fleets Inn 3.45PM Fintown Post -

Donegal County Development Board Bord Forbartha Chontae Dhún Na Ngall

Dún na nGall - pobail i d’teagmháil Donegal - community in touch ISSUE 8 JULY 2010 / EAGRÁN 8 IÚIL 2010 ’m delighted to write these few words for inclusion in the Donegal community in News 2 touch ezine. Wherever you may be in the I Donegal Business 7 world I hope things are good with you. Education and Learning 10 I know what it’s like to find myself far from home at times but in my case I’m fortunate Social and Cultural 12 enough that I get to return on a regular Donegal Community Links 15 basis. I know that sometimes people get fed up with me going on about how great Donegal is but I cant say anything else. I Message From Mayor feel very lucky to have been born and brought up in Kincasslagh. When I was A Chara a child I thought it was the centre of the universe. Everyone was the same. There For the past few years my wife Majella It is my pleasure to introduce to you another was no big or small. Every door was open edition of the Donegal Community in Touch to step through be it day or night. Because and I have lived in Meenbanad. When I sit at the window in the sunroom (far e-zine. I was elected Mayor of your County I worked in The Cope in the village I got on the 30th June 2010. I am the first ever to know everyone both old and young. I from sunrooms I was reared) I can see Keadue Bar nestle between Cruit Island female Mayor in Donegal and only the was only at national school at the time but second ever female Caithaoirligh. -

30Th September 2018 Tel: 074 95 42935 - Email: [email protected] - Kincasslagh Parish - Web: - SVP 087 050 7895

Kincasslagh Parish Newsletter, 30th September 2018 Tel: 074 95 42935 - Email: [email protected] - Kincasslagh Parish - Web: www.kincasslagh.ie - SVP 087 050 7895 Schedule of Masses Facebook (Rosses NYP - Foroige) for more required. Permission from dead persons Training will be provided. If you’d like more St. Mary’s Church, Kincasslagh details for registrations TXT 086 828 0149 relatives will be required. If a dead person information on becoming a volunteer please Next Weekend has no living relatives left then their names contact; Saturday @ 6.30 p.m. Do this In Memory will be allowed to be included. Deirdre Murphy, Irish Cancer Society Tel: 01 Sunday @ 10.00 a.m. There will be a meeting for parents of first Hugh Rodgers: 087 767 8206 Arranmore 231 0564 or [email protected] Next Week Communion Classes in the Community Tommy Gallagher : 0044 776 853 3991 Tuesday @ 1.00 p.m. in Keadue School. Centre next Thursday at 7.00 p.m. to outline Killybegs, Kilcar, Dunkineely, Donegal Town, Rosary on the Coast for Life and Faith Wednesday @ 7.00 p.m. the programme, give the necessary books to Mountcharles, Ardara A gathering will take place on Sunday Friday @ 7.00 p.m. parents and to receive the timetable and Conal Frances Gallagher : 087 230 3610 October 7th at 2.30 p.m. at Belcruit St. Columba’s Church, Acres the jobs that go along with the programme. Dungloe, Meenacross, Lettermacaward, Graveyard Car Park to join tens of thousands Next Weekend Next Saturday evening in St. Mary’s will be Glenties, Portnoo, Glenfinn of faithful along the coast of Ireland and in Sunday @ 11.30 a.m. -

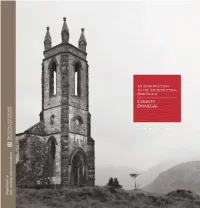

AN INTRODUCTION to the ARCHITECTURAL HERITAGE of COUNTY DONEGAL

AN INTRODUCTION TO THE ARCHITECTURAL HERITAGE of COUNTY DONEGAL AN INTRODUCTION TO THE ARCHITECTURAL HERITAGE of COUNTY DONEGAL COUNTY DONEGAL Mount Errigal viewed from Dunlewey. Foreword County Donegal has a rich architectural seventeenth-century Plantation of Ulster that heritage that covers a wide range of structures became a model of town planning throughout from country houses, churches and public the north of Ireland. Donegal’s legacy of buildings to vernacular houses and farm religious buildings is also of particular buildings. While impressive buildings are significance, which ranges from numerous readily appreciated for their architectural and early ecclesiastical sites, such as the important historical value, more modest structures are place of pilgrimage at Lough Derg, to the often overlooked and potentially lost without striking modern churches designed by Liam record. In the course of making the National McCormick. Inventory of Architectural Heritage (NIAH) The NIAH survey was carried out in phases survey of County Donegal, a large variety of between 2008 and 2011 and includes more building types has been identified and than 3,000 individual structures. The purpose recorded. In rural areas these include structures of the survey is to identify a representative as diverse as bridges, mills, thatched houses, selection of the architectural heritage of barns and outbuildings, gate piers and water Donegal, of which this Introduction highlights pumps; while in towns there are houses, only a small portion. The Inventory should not shopfronts and street furniture. be regarded as exhaustive and, over time, other A maritime county, Donegal also has a rich buildings and structures of merit may come to built heritage relating to the coast: piers, light. -

A Catalogue of Irish Pollen Diagrams

SHORT COMMUNICATION A CATALOGUE OF IRISH POLLEN DIAGRAMS F.J.G. Mitchell, B.S. Stefanini and R. Marchant ABSTRACT The fi rst Irish pollen diagram was published by Gunnar Erdtman in the Irish Naturalists’ Journal in 1927. Since then over 475 pollen diagrams have been produced from locations throughout Ireland from a range of sites and time spans. The data from these pollen diagrams can be used to reconstruct vegetation dynamics over long timescales and so facilitate the investigation of climate change impacts, plant migration and the scale of human-induced landscape change. In this paper we collate the available data from Irish pollen sites into the Irish Pollen Site Database (IPOL) to illustrate their distribution and range. It is intended that this database will be a useful research resource for anyone investigating Irish vegetation history. The database also links to the European and global research agenda surrounding impacts of climate change on ecosystems and associated livelihoods. The IPOL database can be accessed online at www.ipol.ie. F.J.G. Mitchell (corresponding author; email: fraser. [email protected]) and INTRODUCTION macrofossils and pollen from 44 locations across B.S. Stefanini, Botany the country (Jessen 1949). This was supplemented Department, Trinity Investigation of pollen preserved in peat and with additional investigations by Frank Mitchell College Dublin, lake sediments provides reconstructions of long- (Mitchell 1951). These combined works provid- Dublin 2, Ireland; R. ed 84 pollen diagrams. Later work has focused Marchant, Botany term vegetation change. These reconstructions Department, Trinity have a variety of applications such as quantifying on more detailed single-site investigations and College Dublin, climate change impacts, providing archaeologi- expanded to include lake sediments as the tech- Dublin 2 and York cal context and exploring plant migrations and nology to abstract lacustrine sedimentary deposits Institute for Tropical introductions (Mitchell 2011). -

Killybegs Harbour Centre & South West Donegal, Ireland Access To

Killybegs Harbour Centre & South West Donegal, Ireland Area Information Killybegs is situated on the North West Coast of Ireland with the newest harbour facility in the country which opened in 2004. The area around the deep fjord-like inlet of Killybegs has been inhabited since prehistoric times. The town was named in early Christian times, the Gaelic name Na Cealla Beaga referring to a group of monastic cells. Interestingly, and perhaps surprisingly in a region not short of native saints, the town’s patron saint is St. Catherine of Alexandria. St. Catherine is the patron of seafarers and the association with Killybegs is thought to be from the 15th Century which confirms that Killybeg’s tradition of seafaring is very old indeed. The area is rich in cultural & historical history having a long association with marine history dating back to the Spanish Armada. Donegal is renowned for the friendliness & hospitality of its people and that renowned ‘Donegal Welcome’ awaits cruise passengers & crew to the area from where a pleasant travel distance through amazing sea & mountain scenery of traditional picturesque villages with thatched cottages takes you to visit spectacular castles and national parks. Enjoy the slow pace of life for a day while having all the modern facilities of city life. Access to the area Air access Regular flights are available from UK airports and many European destinations to Donegal Airport which is approx an hour’s drive from Killybegs City of Derry Airport approx 1 hour 20 mins drive from Kilybegs International flights available to and from Knock International Airport 2 hours and 20 minutes drive with public transport connections. -

Donegal Primary Care Teams Clerical Support

Donegal Primary Care Teams Clerical Support Office Network PCT Name Telephone Mobile email Notes East Finn Valley Samantha Davis 087 9314203 [email protected] East Lagan Marie Conwell 074 91 41935 086 0221665 [email protected] East Lifford / Castlefin Marie Conwell 074 91 41935 086 0221665 [email protected] Inishowen Buncrana Mary Glackin 074 936 1500 [email protected] Inishowen Carndonagh / Clonmany Christina Donaghy 074 937 4206 [email protected] Fax: 074 9374907 Inishowen Moville Christina Donaghy 074 937 4206 [email protected] Fax: 074 9374907 Letterkenny / North Letterkenny Ballyraine Noelle Glackin 074 919 7172 [email protected] Letterkenny / North Letterkenny Railway House Noelle Glackin 074 919 7172 [email protected] Letterkenny / North Letterkenny Scally Place Margaret Martin 074 919 7100 [email protected] Letterkenny / North Milford / Fanad Samantha Davis 087 9314203 [email protected] North West Bunbeg / Derrybeg Contact G. McGeady, Facilitator North West Dungloe Elaine Oglesby 074 95 21044 [email protected] North West Falcarragh / Dunfanaghy Contact G. McGeady, Facilitator Temporary meeting organisation South Ardara / Glenties by Agnes Lawless, Ballyshannon South Ballyshannon / Bundoran Agnes Lawless 071 983 4000 [email protected] South Donegal Town Marion Gallagher 074 974 0692 [email protected] Temporary meeting organisation South Killybegs by Agnes Lawless, Ballyshannon PCTAdminTypeContactsV1.2_30July2013.xls Donegal Primary Care Team Facilitators Network Area PCT Facilitator Address Email Phone Mobile Fax South Donegal Ballyshannon/Bundoran Ms Sandra Sheerin Iona Office Block [email protected] 071 983 4000 087 9682067 071 9834009 Killybegs/Glencolmkille Upper Main Street Ardara/Glenties Ballyshannon Donegal Town Areas East Donegal Finn Valley, Lagan Valley, Mr Peter Walker Social Inclusion Dept., First [email protected] 074 910 4427 087 1229603 & Lifford/Castlefin areas Floor, County Clinic, St. -

Why Donegal Slept: the Development of Gaelic Games in Donegal, 1884-1934

WHY DONEGAL SLEPT: THE DEVELOPMENT OF GAELIC GAMES IN DONEGAL, 1884-1934 CONOR CURRAN B.ED., M.A. THESIS FOR THE DEGREE OF PH.D. THE INTERNATIONAL CENTRE FOR SPORTS HISTORY AND CULTURE AND THE DEPARTMENT OF HISTORICAL AND INTERNATIONAL STUDIES DE MONTFORT UNIVERSITY LEICESTER SUPERVISORS OF RESEARCH: FIRST SUPERVISOR: PROFESSOR MATTHEW TAYLOR SECOND SUPERVISOR: PROFESSOR MIKE CRONIN THIRD SUPERVISOR: PROFESSOR RICHARD HOLT APRIL 2012 i Table of Contents Acknowledgements iii Abbreviations v Abstract vi Introduction 1 Chapter 1 Donegal and society, 1884-1934 27 Chapter 2 Sport in Donegal in the nineteenth century 58 Chapter 3 The failure of the GAA in Donegal, 1884-1905 104 Chapter 4 The development of the GAA in Donegal, 1905-1934 137 Chapter 5 The conflict between the GAA and association football in Donegal, 1905-1934 195 Chapter 6 The social background of the GAA 269 Conclusion 334 Appendices 352 Bibliography 371 ii Acknowledgements As a rather nervous schoolboy goalkeeper at the Ian Rush International soccer tournament in Wales in 1991, I was particularly aware of the fact that I came from a strong Gaelic football area and that there was only one other player from the south/south-west of the county in the Donegal under fourteen and under sixteen squads. In writing this thesis, I hope that I have, in some way, managed to explain the reasons for this cultural diversity. This thesis would not have been written without the assistance of my two supervisors, Professor Mike Cronin and Professor Matthew Taylor. Professor Cronin’s assistance and knowledge has transformed the way I think about history, society and sport while Professor Taylor’s expertise has also made me look at the writing of sports history and the development of society in a different way. -

Irish Landscape Names

Irish Landscape Names Preface to 2010 edition Stradbally on its own denotes a parish and village); there is usually no equivalent word in the Irish form, such as sliabh or cnoc; and the Ordnance The following document is extracted from the database used to prepare the list Survey forms have not gained currency locally or amongst hill-walkers. The of peaks included on the „Summits‟ section and other sections at second group of exceptions concerns hills for which there was substantial www.mountainviews.ie The document comprises the name data and key evidence from alternative authoritative sources for a name other than the one geographical data for each peak listed on the website as of May 2010, with shown on OS maps, e.g. Croaghonagh / Cruach Eoghanach in Co. Donegal, some minor changes and omissions. The geographical data on the website is marked on the Discovery map as Barnesmore, or Slievetrue in Co. Antrim, more comprehensive. marked on the Discoverer map as Carn Hill. In some of these cases, the evidence for overriding the map forms comes from other Ordnance Survey The data was collated over a number of years by a team of volunteer sources, such as the Ordnance Survey Memoirs. It should be emphasised that contributors to the website. The list in use started with the 2000ft list of Rev. these exceptions represent only a very small percentage of the names listed Vandeleur (1950s), the 600m list based on this by Joss Lynam (1970s) and the and that the forms used by the Placenames Branch and/or OSI/OSNI are 400 and 500m lists of Michael Dewey and Myrddyn Phillips.