Issue No 4 – Autumn 1978

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Property Document

Offers Over Glencorse Self-Catering and Bed & Breakfast £350,000 (Freehold) Drumbeg, Sutherland, IV27 4NW Outstanding detached Situated on the Exceptional hillwalking directly Trading as a well- Attractive garden grounds Having been tastefully house, located in a North Coast 500 from the property and established and highly and off-road parking plus an refurbished, Glencorse stunning elevated position tourist route, kayaking or sailing immediately rated self-catering unit upper walled garden, would equally make a with superlative mountain within the small to hand (3 minutes’ walk to with 4 bedrooms and currently a BBQ terrace area, uniquely beautiful family and loch views plus coastal Coastal village of Drumbeg beach or to Loch generous amenity offering some development home; subject to views behind the property Drumbeg Drumbeg jetty) space potential (STPP) consents DESCRIPTION Glencorse is a charming and beautifully presented 4-bedroom detached self-catering unit and bed and breakfast business. The subjects are located in an elevated setting with truly stunning views over Loch Drumbeg. This substantial property is situated centrally to the hamlet of Drumbeg with services immediately to hand. An imposing and attractive stone-built house dating from around 1820. This attractively decorated property reflects a high level of modern comfort. The house boasts a characterful ambience and offers excellent facilities throughout balancing the retained historic features with modern comfort. The owner has made considerable investment this year in replacing the entire linen used within the business. Glencorse is a traditionally built, former school house with unusually high ceilings and appealing period features. It has a well maintained garden popular with a resident deer (known locally as Albert) who is a great attraction with guests. -

2019 Cruise Directory

Despite the modern fashion for large floating resorts, we b 7 nights 0 2019 CRUISE DIRECTORY Highlands and Islands of Scotland Orkney and Shetland Northern Ireland and The Isle of Man Cape Wrath Scrabster SCOTLAND Kinlochbervie Wick and IRELAND HANDA ISLAND Loch a’ FLANNAN Stornoway Chàirn Bhain ISLES LEWIS Lochinver SUMMER ISLES NORTH SHIANT ISLES ST KILDA Tarbert SEA Ullapool HARRIS Loch Ewe Loch Broom BERNERAY Trotternish Inverewe ATLANTIC NORTH Peninsula Inner Gairloch OCEAN UIST North INVERGORDON Minch Sound Lochmaddy Uig Shieldaig BENBECULA Dunvegan RAASAY INVERNESS SKYE Portree Loch Carron Loch Harport Kyle of Plockton SOUTH Lochalsh UIST Lochboisdale Loch Coruisk Little Minch Loch Hourn ERISKAY CANNA Armadale BARRA RUM Inverie Castlebay Sound of VATERSAY Sleat SCOTLAND PABBAY EIGG MINGULAY MUCK Fort William BARRA HEAD Sea of the Glenmore Loch Linnhe Hebrides Kilchoan Bay Salen CARNA Ballachulish COLL Sound Loch Sunart Tobermory Loch à Choire TIREE ULVA of Mull MULL ISLE OF ERISKA LUNGA Craignure Dunsta!nage STAFFA OBAN IONA KERRERA Firth of Lorn Craobh Haven Inveraray Ardfern Strachur Crarae Loch Goil COLONSAY Crinan Loch Loch Long Tayvallich Rhu LochStriven Fyne Holy Loch JURA GREENOCK Loch na Mile Tarbert Portavadie GLASGOW ISLAY Rothesay BUTE Largs GIGHA GREAT CUMBRAE Port Ellen Lochranza LITTLE CUMBRAE Brodick HOLY Troon ISLE ARRAN Campbeltown Firth of Clyde RATHLIN ISLAND SANDA ISLAND AILSA Ballycastle CRAIG North Channel NORTHERN Larne IRELAND Bangor ENGLAND BELFAST Strangford Lough IRISH SEA ISLE OF MAN EIRE Peel Douglas ORKNEY and Muckle Flugga UNST SHETLAND Baltasound YELL Burravoe Lunna Voe WHALSAY SHETLAND Lerwick Scalloway BRESSAY Grutness FAIR ISLE ATLANTIC OCEAN WESTRAY SANDAY STRONSAY ORKNEY Kirkwall Stromness Scapa Flow HOY Lyness SOUTH RONALDSAY NORTH SEA Pentland Firth STROMA Scrabster Caithness Wick Welcome to the 2019 Hebridean Princess Cruise Directory Unlike most cruise companies, Hebridean operates just one very small and special ship – Hebridean Princess. -

2020 Cruise Directory Directory 2020 Cruise 2020 Cruise Directory M 18 C B Y 80 −−−−−−−−−−−−−−− 17 −−−−−−−−−−−−−−−

2020 MAIN Cover Artwork.qxp_Layout 1 07/03/2019 16:16 Page 1 2020 Hebridean Princess Cruise Calendar SPRING page CONTENTS March 2nd A Taste of the Lower Clyde 4 nights 22 European River Cruises on board MS Royal Crown 6th Firth of Clyde Explorer 4 nights 24 10th Historic Houses and Castles of the Clyde 7 nights 26 The Hebridean difference 3 Private charters 17 17th Inlets and Islands of Argyll 7 nights 28 24th Highland and Island Discovery 7 nights 30 Genuinely fully-inclusive cruising 4-5 Belmond Royal Scotsman 17 31st Flavours of the Hebrides 7 nights 32 Discovering more with Scottish islands A-Z 18-21 Hebridean’s exceptional crew 6-7 April 7th Easter Explorer 7 nights 34 Cruise itineraries 22-97 Life on board 8-9 14th Springtime Surprise 7 nights 36 Cabins 98-107 21st Idyllic Outer Isles 7 nights 38 Dining and cuisine 10-11 28th Footloose through the Inner Sound 7 nights 40 Smooth start to your cruise 108-109 2020 Cruise DireCTOrY Going ashore 12-13 On board A-Z 111 May 5th Glorious Gardens of the West Coast 7 nights 42 Themed cruises 14 12th Western Isles Panorama 7 nights 44 Highlands and islands of scotland What you need to know 112 Enriching guest speakers 15 19th St Kilda and the Outer Isles 7 nights 46 Orkney, Northern ireland, isle of Man and Norway Cabin facilities 113 26th Western Isles Wildlife 7 nights 48 Knowledgeable guides 15 Deck plans 114 SuMMER Partnerships 16 June 2nd St Kilda & Scotland’s Remote Archipelagos 7 nights 50 9th Heart of the Hebrides 7 nights 52 16th Footloose to the Outer Isles 7 nights 54 HEBRIDEAN -

Where to Go: Puffin Colonies in Ireland Over 15,000 Puffin Pairs Were Recorded in Ireland at the Time of the Last Census

Where to go: puffin colonies in Ireland Over 15,000 puffin pairs were recorded in Ireland at the time of the last census. We are interested in receiving your photos from ANY colony and the grid references for known puffin locations are given in the table. The largest and most accessible colonies here are Great Skellig and Great Saltee. Start Number Site Access for Pufferazzi Further information Grid of pairs Access possible for Puffarazzi, but Great Skellig V247607 4,000 worldheritageireland.ie/skellig-michael check local access arrangements Puffin Island - Kerry V336674 3,000 Access more difficult Boat trips available but landing not possible 1,522 Access possible for Puffarazzi, but Great Saltee X950970 salteeislands.info check local access arrangements Mayo Islands l550938 1,500 Access more difficult Illanmaster F930427 1,355 Access more difficult Access possible for Puffarazzi, but Cliffs of Moher, SPA R034913 1,075 check local access arrangements Stags of Broadhaven F840480 1,000 Access more difficult Tory Island and Bloody B878455 894 Access more difficult Foreland Kid Island F785435 370 Access more difficult Little Saltee - Wexford X968994 300 Access more difficult Inishvickillane V208917 170 Access more difficult Access possible for Puffarazzi, but Horn Head C005413 150 check local access arrangements Lambay Island O316514 87 Access more difficult Pig Island F880437 85 Access more difficult Inishturk Island L594748 80 Access more difficult Clare Island L652856 25 Access more difficult Beldog Harbour to Kid F785435 21 Access more difficult Island Mayo: North West F483156 7 Access more difficult Islands Ireland’s Eye O285414 4 Access more difficult Howth Head O299389 2 Access more difficult Wicklow Head T344925 1 Access more difficult Where to go: puffin colonies in Inner Hebrides Over 2,000 puffin pairs were recorded in the Inner Hebrides at the time of the last census. -

Marine Fish Farm at Loch Kanaird, Eastern Side Of

THE HIGHLAND COUNCIL Agenda Item 6.2 NORTH PLANNING APPLICATIONS COMMITTEE Report No PLN/092/13 22 October 2013 13/01494/FUL: Wester Ross Fisheries Ltd Loch Kanaird, Eastern Side Of Isle Martin Report by Head of Planning and Building Standards SUMMARY Description : Marine Fish Farm (Atlantic Salmon) Alterations to existing site to create single group of 46 square steel pens each 15m x 15m and allow for the installation of an automated feed barge. Recommendation - GRANT planning permission Ward : 06 - Wester Ross, Strathpeffer and Lochalsh Development category : Local Pre-determination hearing : None Reason referred to Committee : More than 5 objections and objection from consultee which cannot be resolved by conditions. 1. PROPOSED DEVELOPMENT 1.1 The proposed development involves replacement of equipment at an existing salmon farm and addition of a feed barge. This would expand the physical installation (a31% increase in the total cage area) but the moorings area required would be more compact (a 37% decrease). The two groups of existing square cages, one steel and the other wood, would be replaced by a single group of 46 square steel cages each 15m x 15m. The developer also wishes to install a 150-tonne capacity automated feed barge 10m x 14.5m by 5.5m high when empty to distribute feed to the fish cages. The applicant intends to install moorings between the fish farm installation and Isle Martin to allow the mooring of harvesting raft and similar equipment when they are not in use. 1.2 The applicant is of the view that the existing ageing cage configuration is no longer fit for purpose. -

The Minor Intrusions of Assynt, NW Scotland: Early Development of Magmatism Along the Caledonian Front

Mineralogical Magazine, August 2004, Vol. 68(4), pp. 541–559 The minor intrusions of Assynt, NW Scotland: early development of magmatism along the Caledonian Front 1, 2,3 4 K. M. GOODENOUGH *, B. N. YOUNG AND I. PARSONS 1 British Geological Survey, West Mains Road, Edinburgh EH9 3LA, UK 2 Department of Geology and Mineralogy, University of Aberdeen, Marischal College, Broad Street, Aberdeen AB24 3UE, UK 3 Baker Hughes Inteq, Barclayhill Place, Portlethen, Aberdeen AB12 4PF, UK 4 Grant Institute of Earth Science, University of Edinburgh, West Mains Road, Edinburgh EH9 3JW, UK ABSTRACT The Assynt Culmination of the Moine Thrust Belt, in the northwest Scottish Highlands, contains a variety of Caledonian alkaline and calc-alkaline intrusions that are mostly of Silurian age. These include a significant but little-studied suite of dykes and sills, the Northwest Highlands Minor Intrusion Suite. We describe the structural relationships of these minor intrusions and suggest a classification into seven swarms. The majority of the minor intrusions can be shown to pre-date movement in the Moine Thrust Belt, but some appear to have been intruded duringthe period of thrusting.A complex history of magmatism is thus recorded within this part of the Moine Thrust Belt. New geochemical data provide evidence of a subduction-related component in the mantle source of the minor intrusions. KEYWORDS: Assynt, Caledonian, minor intrusion, Moine Thrust, Scotland. Introduction north of Assynt, to the Achall valley near Ullapool, but they are most abundant in the Assynt area. The WITHIN the Assynt Culmination of the Moine minor intrusions constitute a significant part of the Thrust Belt of NW Scotland (Fig. -

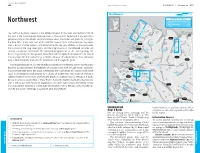

NORTHWEST © Lonelyplanetpublications Northwest Northwest 256 and Thedistinctive, Seeminglyinaccessiblepeakstacpollaidh

© Lonely Planet Publications 256 www.lonelyplanet.com NORTHWEST •• Information 257 0 10 km Northwest 0 6 miles Northwest – Maps Cape Wrath 1 Sandwood Bay & Cape Wrath p260 Northwest Faraid 2 Ben Loyal p263 Head 3 Eas a' Chùal Aluinn p266 H 4 Quinag p263 Durness C Sandwood Creag Bay S Riabach Keoldale t (485m) To Thurso The north of Scotland, beyond a line joining Ullapool in the west and Dornoch Firth in r Kyle of N a (20mi) t Durness h S the east, is the most sparsely populated part of the country. Sutherland is graced with a h i n Bettyhill I a r y 1 Blairmore A838 Hope of Tongue generous share of the wildest and most remote coast, mountains and glens. At first sight, Loch Eriboll M Kinlochbervie Tongue the bare ‘hills’, more rock than earth, and the maze of lochs and waterways may seem Loch Kyle B801 Cranstackie Hope alien – part of another planet – and unattractive. But the very wildness of the rockscapes, (801m) r Rudha Rhiconich e Ruadh An Caisteal v the isolation of the long, deep glens, and the magnificence of the indented coastline can E (765m) a A838 Foinaven n Laxford (911m) Ben Hope h Loch t exercise a seductive fascination. The outstanding significance of the area’s geology has Bridge (927m) H 2 Loyal a r been recognised by the designation of the North West Highlands Geopark (see the boxed t T Scourie S Loch Ben Stack Stack A836 text on p264 ), the first such reserve in Britain. Intrusive developments are few, and many (721m) long-established paths lead into the mountains and through the glens. -

Hiking Scotland's

Hiking Scotland’s North Highlands & Isle of Lewis July 20-30, 2021 (11 days | 15 guests) with archaeologist Mary MacLeod Rivett Archaeology-focused tours for the curious to the connoisseur. Clachtoll Broch Handa Island Arnol Dun Carloway (5.5|645) (6|890) BORVE Great Bernera & Traigh Uige 3 Caithness Dunbeath(4.5|425) (6|870) Stornoway (5|~) 3 3 BRORA Glasgow Isle of Lewis Callanish Lairg Standing Stones Ullapool (4.5|~) (4.5|885) Ardvreck LOCHINVER Castle Inverness Little Assynt # Overnight stays Itinerary stops Scottish Flights Hikes (miles|feet) Highlands Ferry Archaeological Institute of America Lecturer & Host Dr. Mary MacLeod oin archaeologist Mary MacLeod Rivett and a small group of like- Rivett was born in minded travelers on this 11-day tour of Scotland’s remote north London, England, to J Highlands and the Isle of Lewis in the Outer Hebrides. Mostly we a Scottish-Canadian family. Her father’s will explore off the well-beaten Highland tourist trail, and along the way family was from we will be treated to an abundance of archaeological and historical sites, Scotland’s Outer striking scenery – including high cliffs, sea lochs, sandy and rocky bays, Hebrides, and she mountains, and glens – and, of course, excellent hiking. spent a lot of time in the Hebrides as a child. Mary earned her Scotland’s long and varied history stretches back many thousands of B.A. from the University of Cambridge, years, and archaeological remains ranging from Neolithic cairns and and her M.A. from the University of stone circles to Iron Age brochs (ancient dry stone buildings unique to York. -

ANTARES CHARTS 2020 Full List in Chart Number Order

ANTARES CHARTS 2020 Full list in chart number order. Key at end of list Chart name Number Status Sanda Roads, Sanda Island, edition 1 5517 Y U Pladda Anchorage, South Arran, edition 1 5525 Y N Sound of Pladda, South Arran, edition 1 5526 Y U Kingscross Anchorage, Lamlash Bay, Isle of Arran, editon 1 5530 Y N Holy Island Anchorage, Lamlash Bay, Isle of Arran, edition 1 5531 Y N Lamlash Anchorage, Lamlash Bay, Isle of Arran, edition 1 5532 Y N Port Righ, Carradale, Kilbrannan Sound, edition 1 5535 Y U Brodick Old Quay Anchorage, Isle of Arran,edition 1 5535 YA N Lagavulin Bay, Islay, edition 2 5537 A U Loch Laphroaig, Islay, edition 2 5537 B C Chapel Bay, Texa, edition 1 5537 C U Caolas an Eilein, Texa, edition 1 5537 D U Ardbeg & Loch an t-Sailein, edition 3 5538 A U Cara Reef Bay, Gigha, edition 2 5538 B C Loch an Chnuic, edition 3 5539 A C Port an Sgiathain, Gigha, edition 2 5539 B C Caolas Gigalum, Gigha, edition 1 5539 C N North Gigalum Anchorge, Gigha, edition 1 5539 D N Ardmore Islands, East Islay, edition 5 5540 A C Craro Bay, Gigha, edition 2 5540 B C Port Gallochoille, Gigha, edition 2 5540 C C Ardminish Bay, Gigha, edition 3 5540 D M Glas Uig, East Coast of Islay, edition 3 5541 A C Port Mor, East Islay, edition 2 5541 B C Aros Bay, East Islay, edition 2 5541 C C Ardminish Point Passage, Gigha, edition 2 5541 D C Druimyeon Bay, Gigha, edition 1 5541 E N West Tarbert Bay, South Anchorage, Gigha, edition 2 5542 A C East Tarbert Bay, Gigha, edition 2 5542 B C Loch Ranza, Isle of Arran, edition 2 5542 Y M Bagh Rubha Ruaidh, West Tarbert -

GEOLOGICAL GROUP, IPSWICH. JULY 1969 BULLETIN No. 6

GEOLOGICAL GROUP, IPSWICH. JULY 1969 BULLETIN No. 6. ------------------------------------------------------------------------------- FIELDTRIP TO CORNWALL AND SOUTH DEVON, SEPTEMBER 1968. The primary object of the fieldtrip to Cornwall and South Devon on 14-19 September1968 was to visit the St. Erth Beds (near Hayle, Cornwall), the fauna of which is probably of Crag age (s.l.). Two members had visited the site on a previous occasion. Informal discussions were held and it was decided to travel by van and to camp at our destination. Two vans (a 15-cwt. and a 5-cwt.) were available and tents and cooking equipment were hired from the Ipswich Education Office (Mr. Britten of their staff was most helpful), supplemented by members equipment. A meeting was held a few days before departure, and members were given the itinerary and a list of personal and domestic items thought desirable. Each person was also required to bring a certain amount of food, e,g. jam, baked beans, butter, sugar, tinned meat - this was given with enough generosity that our estimated food bills were to be cut considerably. A tent- pitching practise was held the day before leaving. Nine people (Messrs. C. Garrod, P. Grainger, T. Jones, S. MacFarlane and R. Markham, and the Misses P. Cresswell M. Daniels, S. Giles, and L. Hyde) formed the final party. Their equipment was collected some hours before departure, and participants met in the town centre, that the vans could leave Ipswich at 11p.m. on Saturday 14 September. After driving through the night, Sunday breakfast was obtained in Salisbury, before pressing on to Okehampton and our first geological stop. -

Hutton S Geological Tours 1

Science & Education James Hutton's Geological Tours of Scotland: Romanticism, Literary Strategies, and the Scientific Quest --Manuscript Draft-- Manuscript Number: Full Title: James Hutton's Geological Tours of Scotland: Romanticism, Literary Strategies, and the Scientific Quest Article Type: Research Article Keywords: James Hutton; geology; literature; Romanticism; travel writing; Scotland; landscape. Corresponding Author: Tom Furniss University of Strathclyde Glasgow, UNITED KINGDOM Corresponding Author Secondary Information: Corresponding Author's Institution: University of Strathclyde Corresponding Author's Secondary Institution: First Author: Tom Furniss First Author Secondary Information: All Authors: Tom Furniss All Authors Secondary Information: Abstract: Rather than focussing on the relationship between science and literature, this article attempts to read scientific writing as literature. It explores a somewhat neglected element of the story of the emergence of geology in the late eighteenth century - James Hutton's unpublished accounts of the tours of Scotland that he undertook in the years 1785 to 1788 in search of empirical evidence for his theory of the earth. Attention to Hutton's use of literary techniques and conventions highlights the ways these texts dramatise the journey of scientific discovery and allow Hutton's readers to imagine that they were virtual participants in the geological quest, conducted by a savant whose self-fashioning made him a reliable guide through Scotland's geomorphology and the landscapes of -

Lasswade & Kevock Conservation Area

Lasswade & Kevock Conservation Area Midlothian LASSWADE & KEVOCK CONSERVATION AREA Midlothian Strategic Services Fairfield House 8 Lothian Road Dalkeith EH22 3ZN Tel: 0131 271 3473 Fax: 0131 271 3537 www.midlothian.gov.uk 1 Lasswade & Kevock Conservation Area Midlothian Lasswade and Kevock CONTENTS Preface Page 3 Planning Context Page 4 Location and Population Page 5 Date of Designation Page 5 Archaeology and History Page 5 Character Analysis Lasswade Setting and Views Page 8 Urban Structure Page 8 Key Buildings Page 9 Architectural Character Page 10 Landscape Character Page 12 Issues Page 13 Enhancement Opportunities Page 13 Kevock Setting and Views Page 14 Urban Structure Page 14 Key Buildings Page 15 Architectural Character Page 15 Landscape Character Page 16 Issues Page 17 Enhancement Opportunities Page 17 Issues Applicable to the Whole Conservation Area Page 17 Character Analysis Map Page 19 Listed Buildings Page 20 Conservation Area Boundary Page 25 Conservation Area Boundary Map Page 26 Article 4 Direction Order Page 27 Building Conservation Principles Page 28 Glossary Page 30 References Page 33 2 Lasswade & Kevock Conservation Area Midlothian PREFACE attention to the character and appearance of the area when Conservation Areas exercising its powers under planning legislation. Conservation area status 1 It is widely accepted that the historic means that the character and environment is important and that a appearance of the conservation area high priority should be given to its will be afforded additional conservation and sensitive protection through development management. This includes plan policies and other planning buildings and townscapes of historic guidance that seeks to preserve and or architectural interest, open enhance the area whilst managing spaces, historic gardens and change.