Dissertation 042511 Ds Edits 1614Pm

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

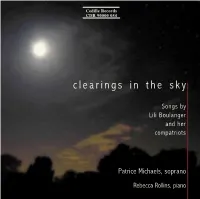

Clearings in the Sky

Cedille Records CDR 90000 054 c l e a r i n g s i n t h e s k y Songs by Lili Boulanger and her compatriots Patrice Michaels, soprano Rebecca Rollins, piano DDD Absolutely Digital™ CDR 90000 054 clearings in the sky GABRIEL FAURÉ (1845-1924) bm IV. Un poète disait . (1:44) 1 Vocalise-étude . (3:14) bn V. Au pied de mon lit . (2:23) 2 Tristesse . (2:51) bo VI. Si tout ceci n’est qu’un pauvre rêve . (2:28) 3 En prière . (2:46) bp VII. Nous nous aimerons tant . (2:49) LILI BOULANGER (1893-1918) bq VIII. Vous m’avez regardé avec toute votre âme . (1:32) 4 Reflets . (3:02) br IX. Les lilas qui avaient fleuri . (2:36) 5 Attente . (2:21) bs X. Deux ancolies . (1:20) 6 Le retour . (5:35) bt XI. Par ce que j’ai souffert . (3:01) MAURICE RAVEL (1875-1937) ck XII. Je garde une médaille d’elle . (1:59) 7 Pièce en forme de Habañera . (3:46) cl XIII. Demain fera un an . (8:42) CLAUDE DEBUSSY (1862-1918) OLIVIER MESSIAEN (1908-1992) 8 Le jet d’eau . (6:05) cm Le sourire . (1:35) LILI BOULANGER: Clairières dans le ciel (36:25) ARTHUR HONEGGER (1892-1955) 9 I. Elle était descendue au bas de la prairie . (2:00) cn Vocalise-étude . (2:11) bk II. Elle est gravement gaie . (1:47) LILI BOULANGER bl III. Parfois, je suis triste . (3:37) co Dans l’immense tristesse . (5:51) Patrice Michaels, soprano Rebecca Rollins, piano TT: (76:35) ./ Cedille Records is a trademark of The Chicago Classical Recording Foundation, a not-for-profit foundation devoted to promoting the finest musicians and ensembles in the Chicago area. -

Li-Li Boo-Lan-Jeh

Lili Boulanger Li-li Boo-lan-jeh (j is a soft g sound as in genre) Born: August 21st, 1893, Paris, France Died: March 15th, 1918, Mézy-sur-Seine, France “To study music, we must learn the rules. To create music, we must Period of Music: 20th Century, Modern break them.” – Nadia Boulanger, Lili’s beloved sister and teacher Biography: Lili Boulanger was born in 1893 in Paris, France to a musical family. Her mother, father, and sister Nadia were all trained composers or performers. When her father, Ernest, was only 20, he won the Prix de Rome. This coveted prize, which provided a year’s study in Rome, was the greatest recognition a young French composer could attain. Other winners of this prestigious award include Hector Berlioz, Gabriel Fauré, and Claude Debussy. Ernest Boulanger was 62 when he married a Russian princess. He was 72 years old when Nadia was born and 79 when Lili was born. He died when both children were still young. Lili’s immense talent was recognized early on, and at the age of 2 she began receiving musical training from her mom and eventually her older sister. In 1895 she contracted bronchial pneumonia, after which she was constantly ill. Because of her frail health, she relied entirely on private study since she was too weak to obtain a full music education at the Conservatoire. In 1913, Lili became the first woman to win the Prix de Rome for her Cantata Faust et Helene at the age of 20, the same age her father was when he won this award. -

We Are Proud to Offer to You the Largest Catalog of Vocal Music in The

Dear Reader: We are proud to offer to you the largest catalog of vocal music in the world. It includes several thousand publications: classical,musical theatre, popular music, jazz,instructional publications, books,videos and DVDs. We feel sure that anyone who sings,no matter what the style of music, will find plenty of interesting and intriguing choices. Hal Leonard is distributor of several important publishers. The following have publications in the vocal catalog: Applause Books Associated Music Publishers Berklee Press Publications Leonard Bernstein Music Publishing Company Cherry Lane Music Company Creative Concepts DSCH Editions Durand E.B. Marks Music Editions Max Eschig Ricordi Editions Salabert G. Schirmer Sikorski Please take note on the contents page of some special features of the catalog: • Recent Vocal Publications – complete list of all titles released in 2001 and 2002, conveniently categorized for easy access • Index of Publications with Companion CDs – our ever expanding list of titles with recorded accompaniments • Copyright Guidelines for Music Teachers – get the facts about the laws in place that impact your life as a teacher and musician. We encourage you to visit our website: www.halleonard.com. From the main page,you can navigate to several other areas,including the Vocal page, which has updates about vocal publications. Searches for publications by title or composer are possible at the website. Complete table of contents can be found for many publications on the website. You may order any of the publications in this catalog from any music retailer. Our aim is always to serve the singers and teachers of the world in the very best way possible. -

1J131J Alexander Boggs Ryan,, Jr., B

omit THE PIANO STYLE OF CLAUDE DEBUSSY THESIS Presented to the Graduate Council of the North Texas State College in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For the Degree of MASTER OF MUSIC by 1J131J Alexander Boggs Ryan,, Jr., B. M. Longview, Texas June, 1951 19139 TABLE OF CONTENTS Page LIST OF ILLUSTRATIONS . , . iv Chapter I. THE DEVELOPMENT OF THE PIANO AS AN INFLUENCE ON STYLE . , . , . , . , . , . ., , , 1 II. DEBUSSY'S GENERAL MUSICAL STYLE . IS Melody Harmony Non--Harmonic Tones Rhythm III. INFLUENCES ON DEBUSSY'S PIANO WORKS . 56 APPENDIX (CHRONOLOGICAL LIST 0F DEBUSSY'S COMPLETE WORKS FOR PIANO) . , , 9 9 0 , 0 , 9 , , 9 ,9 71 BIBLIOGRAPHY *0 * * 0* '. * 9 9 9 9 9 9 9 9 9 9 .9 76 111 LIST OF ILLUSTRATIONS Figure Page 1. Range of the piano . 2 2. Range of Beethoven Sonata 10, No.*. 3 . 9 3. Range of Beethoven Sonata .2. 111 . , . 9 4. Beethoven PR. 110, first movement, mm, 25-27 . 10 5. Chopin Nocturne in D Flat,._. 27,, No. 2 . 11 6. Field Nocturne No. 5 in B FlatMjodr . #.. 12 7. Chopin Nocturne,-Pp. 32, No. 2 . 13 8. Chopin Andante Spianato,,O . 22, mm. 41-42 . 13 9. An example of "thick technique" as found in the Chopin Fantaisie in F minor, 2. 49, mm. 99-101 -0 --9 -- 0 - 0 - .0 .. 0 . 15 10. Debussy Clair de lune, mm. 1-4. 23 11. Chopin Berceuse, OR. 51, mm. 1-4 . 24 12., Debussy La terrasse des audiences du clair de lune, mm. 32-34 . 25 13, Wagner Tristan und Isolde, Prelude to Act I, . -

Boston Symphony Orchestra Concert Programs, Season 61,1941-1942

SYMPHONY HALL, BOSTON HUNTINGTON AND MASSACHUSETTS AVENUES Telephone, Commonwealth 1492 SIXTY-FIRST SEASON, 1941-1942 CONCERT BULLETIN of the Boston Symphony Orchestra SERGE KOUSSEVITZKY, Conductor Richard Burgin, Assistant Conductor with historical and descriptive notes bv John N. Burk COPYRIGHT, 1941, BY BOSTON SYMPHONY ORCHESTRA, ItlC. The OFFICERS and TRUSTEES of the BOSTON SYMPHONY ORCHESTRA, Inc. Ernest B. Dane . President Henry B. Sawyer . Vice-President Ernest B. Dane Treasurer Henry B. Cabot N. Penrose Hallowell Ernest B. Dane M. A. De Wolfe Howe Reginald C. Foster Roger I. Lee Alvan T. Fuller Richard C. Paine Jerome D. Greene Henry B. Sawyer Bentley W. Warren G. E. Judd, Manager C. W. Spalding, Assistant Manager [289] In all the world d^afrekart has YIO equal A refreshingly new adventure in music awaits you when listening to your favorite compositions re- produced on the new Capehart. You will be en- tranced to discover new expressions, tonal colorings that have been denied you before. Capehart full range perfect reproductions catch the extreme vel- vety "lows" and the golden threadlike "highs" as well as every intermediate overtone so vital to the correct interpretation of great music. No other instrument can compare with the Cape- hart. Let us reproduce your favorite music for you on one of the new Capeharts we have on display. CHAS. W. HOMEYER CO., Inc. BOYLSTON STREET BOSTON <BiyL HALL-MARK OF GRACIOUS LIVING [290] s SYMPHONIANA For the Hard of Hearing Exhibits Mozart Week FOR THE HARD OF HEARING After months of experimentation, Symphony Hall is now equipped with amplifying apparatus for the hard of hearing. -

The Young Debussy Darren Chase Tenor Mark Cogley Piano

t h e Y o u N g d e B u s s Y darren Chase tenor Mark Cogley piano C r e d i t s engineer: Louis Brown recorded at L. Brown Studios in New York Cover Photo of Daren Chase: David Wentworth Photo of Mark Cogley: Casey Fatchett www.albanyrecords.com TROY1221 albany records u.s. 915 broadway, albany, ny 12207 tel: 518.436.8814 fax: 518.436.0643 albany records u.k. box 137, kendal, cumbria la8 0xd tel: 01539 824008 © 2010 albany records made in the usa ddd waRning: cOpyrighT subsisTs in all Recordings issued undeR This label. 1 Beau soir (Paul Bourget) [2:25] t h e M u s i C 2 Paysage sentimentale (Paul Bourget) [3:20] 3 Voici que le printemps (Paul Bourget) [3:16] The Young Debussy comprises the songs composed by Claude Achille Debussy (1862-1918) before 4 Fleur des blés (André Girod) [2:32] his thirtieth birthday, but includes only those he thought were good enough to publish. (With these exceptions: the 1891 set Trois Poèmes de Verlaine could not be included for lack of space; the 1903 Cinq Poèmes de Charles Baudelaire Dans le jardin has been inserted in its place.) 5 Le balcon [7:41] the vocal writing in these songs varies, but in most of them there is the emphasis on the middle 6 harmonie du soir [4:23] and low range characteristic of much French vocal music. Therefore every downward transposition 7 Le jet d’eau [5:55] has the effect of thickening the texture and darkening the color Debussy had in mind. -

Lili Boulanger (1893–1918) and World War I France: Mobilizing Motherhood and the Good Suffering

Lili Boulanger (1893–1918) and World War I France: Mobilizing Motherhood and the Good Suffering By Anya B. Holland-Barry A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy (Music) at the UNIVERSITY OF WISCONSIN-MADISON 2012 Date of final oral examination: 08/24/2012 This dissertation is approved by the following members of the Final Oral Committee: Susan C. Cook, Professor, Music Charles Dill, Professor, Music Lawrence Earp, Professor, Music Nan Enstad, Professor, History Pamela Potter, Professor, Music i Dedication This dissertation is dedicated to my best creations—my son, Owen Frederick and my unborn daughter, Clara Grace. I hope this dissertation and my musicological career inspires them to always pursue their education and maintain a love for music. ii Acknowledgements This dissertation grew out of a seminar I took with Susan C. Cook during my first semester at the University of Wisconsin. Her enthusiasm for music written during the First World War and her passion for research on gender and music were contagious and inspired me to continue in a similar direction. I thank my dissertation advisor, Susan C. Cook, for her endless inspiration, encouragement, editing, patience, and humor throughout my graduate career and the dissertation process. In addition, I thank my dissertation committee—Charles Dill, Lawrence Earp, Nan Enstad, and Pamela Potter—for their guidance, editing, and conversations that also helped produce this dissertation over the years. My undergraduate advisor, Susan Pickett, originally inspired me to pursue research on women composers and if it were not for her, I would not have continued on to my PhD in musicology. -

Jessica Rivera, Soprano Kelley O'connor, Mezzo-Soprano Robert

CAL PERFORMANCES PRESENTS PROGRAM Sunday, October 13, 2013, 3pm Felix Mendelssohn (1809–1847) Volkslied (O säh ich auf der Heide dort), Hertz Hall Op. 63, No. 5 (1842) Ms. O’Connor & Ms. Rivera Jessica Rivera, soprano Mendelssohn Ich wollt, meine Lieb’ ergösse sich, Kelley O’Connor, mezzo-soprano Op. 63, No. 1 (1836) Robert Spano, piano Ms. O’Connor & Ms. Rivera Claude Debussy (1862–1918) Chansons de Bilitis (1897) PROGRAM I. La Flûte de Pan II. La Chevelure III. Le Tombeau des Naïades Camille Saint-Saëns (1835–1921) El Desdichado (1849) Ms. O’Connor Ms. O’Connor & Ms. Rivera Jonathan Leshnoff (b. 1973) Monica Songs (2012) David Bruce (b. 1970) That Time with You (2013) I. For Where Thou Go, I Will Go I. The Sunset Lawn II. We Cover Thee—Sweet Face II. That Time with You III. I thank You III. Black Dress IV. Greetings from Troy, Illinois IV. Bring Me Again V. So Much Joy World Premiere VI. There’s a Son Born to Naomi Ms. O’Connor World Premiere Ms. Rivera Federico Mompou (1893–1987) Combat del Somni (1942–1948) Gabriela Lena Frank (b. 1972) Selections from The Kitchen Songbook(2013) I. Damunt de tu només les flors II. Aquesta nit un mateix vent I. Honey III. Jo et pressentia com la mar Bay Area Premiere IV. Fes me la vida transparent II. Sofrito Ms. Rivera World Premiere Ms. O’Connor & Ms. Rivera Charles Gounod (1818–1893) La Siesta (1870) Ms. O’Connor & Ms. Rivera Funded by the Koret Foundation, this performance is part of Cal Performances’ 2013–2014 Koret Recital Series, which brings world-class artists to our community. -

The Rite of Spring

The Rite of Spring This weekend we’re afforded the opportunity to experience two seldom-heard works: Dvořák’s piano concerto and Lili Boulanger’s dark-night-of-the-soul set to music, D’un soir triste. Stravinsky’s The Rite of Spring — a watershed in the history of Western classical music — comprises the second half. ILI BOULANGER Born 21 August 1893; Paris, France Died 15 March 1918; Mézy-sur-Seine, France D’un soir triste Composed: 1918 First performance: 6 March 1921; Paris, France (chamber work), 9 May 1992; San Francisco, California (orchestral work) Last MSO performance: MSO premiere Instrumentation: 2 flutes, 2 oboes, English horn, 2 clarinets, bass clarinet, 2 bassoons, contrabassoon, 4 horns, 3 trumpets, 3 trombones, tuba, timpani, percussion (bass drum, suspended cymbals, tam tam), harp, celeste, strings Approximate duration: 9 minutes Lili Boulanger was the younger sister of the noted teacher, conductor, and composer Nadia Boulanger (1887-1979). As a child, she accompanied Nadia to classes at the Paris Conserva- toire. She later studied organ with Louis Vierne. Lili also sang and played piano, violin, cel- lo, and harp. The first woman to receive the Prix de Rome — in 1913, for her cantata Faust et Hélène — her composing life was brief but productive. Her most important works are her psalm settings and other large-scale choral pieces. Fauré admired and promoted her music. D’un soir triste (On a Sad Evening) was written in the final months of her life (often beset by illness, she died at the early age of 24), along with a shorter companion piece, D’un matin de printemps (On a Morning in Spring). -

Student Recital

OLD DOMINION UNIVERSITY Department of Music Student Recital Alyssa Romanelli, soprano Joe Ritchie, piano Diehn Center for the Performing Arts Chandler Recital Hall Friday, April 21, 2017 3:00PM Program Và Godendo Go Enjoying Và godendo vezzoso e bello Joyous, graceful and lovely goes Va Godendo George Frideric Handel (1685-1759) quel ruscello la libertà. That free-flowing little brook, E tra l'erbe con onde chiare And though the grass with clear waves from Serse lieto al mare correndo và. It goes gladly running to the sea. Bel Piacere from Agrippina Bel Piacere Great Pleasure Bel piacere è godere fido amor! It is great pleasure to enjoy a faithful love! questo fà contento il cor. it pleases the heart. Nuit D’etoiles Claude Debussy (1862-1918) Di bellezza non s'apprezza Splendor is not measured by beauty Beau Soir lo splendor; Se non vien d'un fido cor. if it does not come from a faithful heart. Nuit D’etoiles Night of Stars Always True to You in My Fashion Cole Porter (1891-1964) Nuit d'étoiles, Night of stars, from Kiss Me Kate Sous tes voiles, beneath your veils, Sous ta brise et tes parfums, beneath your breeze and your perfumes, Triste lyre sad lyre Qui soupire, which is sighing, Don’t Be Afraid Rika Muranaka (b. 1972) Je rêve aux amours défunts. I dream of bygone loves. La seriene Mélancolie Serene Melancholy from Metal Gear Solid Vient éclore au fond de mon cœur, comes to blooms in the depths of my heart, John Toomey, piano Et j'entends l'âme de ma mie and I hear the soul of my beloved Tyler Harney, saxophone Tressallir dans le bois rêveur quiver in the dreaming wood. -

Lili Bio-Formatted

Lili with fellow Prix de Rome finalists, 1913 Lili Boulanger: An Iron Flower Lili Boulanger was exceptionally talented, born into musical (and perhaps Russian) aristocracy in 1893. Her father Ernest, an opera composer, professor at the Paris Conservatory, and past winner of the prestigious Prix de Rome for composition, was the scion of generations of musicians; her mother, Raïssa Mychetsky, was a purported Russian princess. Sister Nadia, six years her senior, would become a leading light of the Paris Conservatory and the most influential music pedagogue of the 20th century. Fauré, Ravel, Widor, and other luminaries of the French musical world were family friends and mentors. It was Fauré who discovered that 2-year-old Lili had perfect pitch. Tragically, all of Lili’s brilliance and education were ultimately at the mercy of her body. After a childhood bout of bronchial pneumonia weakened her immune system, she suffered from poor health and often debilitating illness throughout her life. Lili was determined from age 16 to win the Prix de Rome. Nadia had tried and failed to win four times, held back largely by politics. Her compositions were considered by her teachers Charles Widor and Raoul Pugno to be the best of the field, but she was a woman. Lili studied intensely and first undertook the grinding competition in 1912, but was forced to drop out due to illness. She made another attempt the following year, deploying her own political stratagems (she solicited letters of support from teachers and mentors), and even used her own physical fragility as a tool. As Anna Beer notes in her chapter on Boulanger (Beer, Anna. -

Audition Repertoire, Please Contact the Music Department at 812.941.2655 Or by E-Mail at AUDITION REQUIREMENTS for VARIOUS DEGREE CONCENTRATIONS

1 AUDITION GUIDE AND SUGGESTED REPERTOIRE 1 2 TABLE OF CONTENTS AUDITION REQUIREMENTS AND GUIDE . 3 SUGGESTED REPERTOIRE Piano/Keyboard . 5 STRINGS Violin . 6 Viola . 7 Cello . 8 String Bass . 10 WOODWINDS Flute . 12 Oboe . 13 Bassoon . 14 Clarinet . 15 Alto Saxophone . 16 Tenor Saxophone . 17 BRASS Trumpet/Cornet . 18 Horn . 19 Trombone . 20 Euphonium/Baritone . 21 Tuba/Sousaphone . 21 PERCUSSION Drum Set . 23 Xylophone-Marimba-Vibraphone . 23 Snare Drum . 24 Timpani . 26 Multiple Percussion . 26 Multi-Tenor . 27 VOICE Female Voice . 28 Male Voice . 30 Guitar . 33 2 3 The repertoire lists which follow should be used as a guide when choosing audition selections. There are no required selections. However, the following lists illustrate Students wishing to pursue the Instrumental or Vocal Performancethe genres, styles, degrees and difficulty are strongly levels encouraged of music that to adhereis typically closely expected to the of repertoire a student suggestionspursuing a music in this degree. list. Students pursuing the Sound Engineering, Music Business and Music Composition degrees may select repertoire that is slightly less demanding, but should select compositions that are similar to the selections on this list. If you have [email protected] questions about. this list or whether or not a specific piece is acceptable audition repertoire, please contact the Music Department at 812.941.2655 or by e-mail at AUDITION REQUIREMENTS FOR VARIOUS DEGREE CONCENTRATIONS All students applying for admission to the Music Department must complete a performance audition regardless of the student’s intended degree concentration. However, the performance standards and appropriaterequirements audition do vary repertoire.depending on which concentration the student intends to pursue.