Policy Spotlight: Hate Crime Laws

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Boundaries of State and Local Power to Regulate Illegal Immigration

Pepperdine Law Review Volume 39 Issue 2 Article 5 1-15-2012 Testing the Borders: The Boundaries of State and Local Power to Regulate Illegal Immigration Brittney M. Lane Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.pepperdine.edu/plr Part of the Immigration Law Commons, and the Jurisdiction Commons Recommended Citation Brittney M. Lane Testing the Borders: The Boundaries of State and Local Power to Regulate Illegal Immigration , 39 Pepp. L. Rev. Iss. 2 (2013) Available at: https://digitalcommons.pepperdine.edu/plr/vol39/iss2/5 This Comment is brought to you for free and open access by the Caruso School of Law at Pepperdine Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Pepperdine Law Review by an authorized editor of Pepperdine Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected], [email protected]. DO NOT DELETE 2/8/2012 3:20 PM Testing the Borders: The Boundaries of State and Local Power to Regulate Illegal Immigration I. INTRODUCTION II. DEFINING THE BORDERS: THE HISTORICAL BOUNDARIES OF STATE AND FEDERAL IMMIGRATION POWERS A. This Land Is My Land: Immigration Power from the Colonial Era to the Constitution B. This Land Is Your Land: Federalizing Immigration Power C. A Hole in the Federal Fence: State Police Power Revisited 1. De Canas v. Bica and the State’s Power to Regulate Local Employment of Illegal Immigrants 2. Plyler v. Doe and Further Recognition that Legitimate State Interests Might Militate in Favor of Allowing State Regulation III. BUILDING THE BORDERS THROUGH STATUTORY REGULATION OF IMMIGRATION IV. -

The Matthew Shepherd Hate Crime and Its Intercultural Implications

Proceedings of the New York State Communication Association Volume 2011 Proceedings of the 69th New York State Article 6 Communication Association 10-18-2012 Misunderstood: The aM tthew hepheS rd Hate Crime and its Intercultural Implications Cameron Muir Roger Williams University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://docs.rwu.edu/nyscaproceedings Part of the Communication Commons Recommended Citation Muir, Cameron (2012) "Misunderstood: The aM tthew Shepherd Hate Crime and its Intercultural Implications," Proceedings of the New York State Communication Association: Vol. 2011, Article 6. Available at: http://docs.rwu.edu/nyscaproceedings/vol2011/iss1/6 This Undergraduate Student Paper is brought to you for free and open access by the Journals at DOCS@RWU. It has been accepted for inclusion in Proceedings of the New York State Communication Association by an authorized administrator of DOCS@RWU. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Muir: Misunderstood: The Matthew Shepherd Hate Crime Misunderstood: The Matthew Shepherd Hate Crime and its Intercultural Implications Cameron Muir Roger Williams University __________________________________________________________________ The increasing vocalization by both supporters and opponents of homosexual rights has launched the topic into the spotlight, reenergizing a vibrant discussion that personally affects millions of Americans and which will determine the direction in which U.S. national policy will develop. This essay serves as a continuation of this discussion, using the Matthew Shepherd hate crime, which occurred in October of 1998, as a focal point around which a detailed analysis of homophobia and masculinity in American culture will emerge. __________________________________________________________________ Synopsis The increasing vocalization by both supporters and opponents of homosexual rights has launched the topic into the spotlight, reenergizing a vibrant discussion that personally affects millions of Americans and which will determine the direction in which U.S. -

Promoting a Queer Agenda for Hate Crime Scholarship

LGBT hate crime : promoting a queer agenda for hate crime scholarship PICKLES, James Available from Sheffield Hallam University Research Archive (SHURA) at: http://shura.shu.ac.uk/24331/ This document is the author deposited version. You are advised to consult the publisher's version if you wish to cite from it. Published version PICKLES, James (2019). LGBT hate crime : promoting a queer agenda for hate crime scholarship. Journal of Hate Studies, 15 (1), 39-61. Copyright and re-use policy See http://shura.shu.ac.uk/information.html Sheffield Hallam University Research Archive http://shura.shu.ac.uk LGBT Hate Crime: Promoting a Queer Agenda for Hate Crime Scholarship James Pickles Sheffield Hallam University INTRODUCTION Hate crime laws in England and Wales have emerged as a response from many decades of the criminal justice system overlooking the structural and institutional oppression faced by minorities. The murder of Stephen Lawrence highlighted the historic neglect and myopia of racist hate crime by criminal justice agencies. It also exposed the institutionalised racism within the police in addition to the historic neglect of minority groups (Macpherson, 1999). The publication of the inquiry into the death of Ste- phen Lawrence prompted a move to protect minority populations, which included the lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender (LGBT) community. Currently, Section 28 of the Crime and Disorder Act (1998) and Section 146 of the Criminal Justice Act (2003) provide courts the means to increase the sentences of perpetrators who have committed a crime aggravated by hostility towards race, religion, sexuality, disability, and transgender iden- tity. Hate crime is therefore not a new type of crime but a recognition of identity-aggravated crime and an enhancement of existing sentences. -

Hate Crimes and Violence Against People Experiencing Homelessness

National Coalition for the Homeless 2201 P. St. NW Washington, DC 20037 Phone: (202) 462-4822 Fax: (202) 462-4823 Email: [email protected] Web page: http://www.nationalhomeless.org Hate Crimes and Violence against People Experiencing Homelessness NCH Fact Sheet # 21 Published by the National Coalition for the Homeless, August 2007 HISTORY OF VIOLENCE Over the past eight years, advocates and homeless shelter workers from around the country have received news reports of men, women and even children being harassed, kicked, set on fire, beaten to death, and even decapitated. From 1999 through 2006, there have been 614 acts of violence by housed people, resulting in 189 murders of homeless people and 425 victims of non-lethal violence in 200 cities from 44 states and Puerto Rico. In response to this barrage of information, the National Coalition for the Homeless (NCH), along with its Civil Rights Work Group, a nationwide network of civil rights and homeless advocates, began compiling documentation of this epidemic. NCH has taken articles and news reports and compiled them into an annual report. The continual size of reports of hate crimes and violence against people experiencing homelessness has led NCH to publish its eighth annual consecutive report, “Hate, Violence, and Death on Main Street USA: A Report on Hate Crimes and Violence Against People Experiencing Homelessness in 2006.” This annual report also includes a eight-year analysis of this widespread epidemic. These reports are available on the NCH website at: www.nationalhomeless.org WHAT IS A HATE CRIME? The term “hate crime” generally conjures up images of cross burnings and lynchings, swastikas on Jewish synagogues, and horrific murders of gays and lesbians. -

US V. Wong Kim

U.S. v. Wong Kim Ark: Barred From His Homeland, One Chinese American’s Fight for Birthright Citizenship By August Neumann Word Count: 2488 Landmark United States Supreme Court cases are ingrained in the minds of many Americans, shaping their view of history; a history known for its tumults and hypocrisies, yet remaining a hopeful memoir steeped in the pursuit of liberty for all people. Belonging in the midst of cases as pivotal and transformative in America's story as Marbury v. Madison or Brown v. Board of Education is a more obscure Supreme Court case: the 1897 case of United States v. Wong Kim Ark. Although cardinal in its decision regarding birthright citizenship for people of all races, the case has largely been overlooked. To effectively analyze this neglected, but important piece of history, one must understand what life was like in America for Chinese immigrants in the late 1800s and how Wong Kim Ark found his way to the U.S. Supreme Court to ultimately defend his right to citizenship. What did U.S. v. Wong Kim Ark do for Chinese communities, if anything, and did it change the way they participated in the social and civic life in California and the broader U.S.? Lastly, where does birthright citizenship stand today? The decision secured birthright citizenship for Chinese Americans, but whether it helped them benefit from that citizenship remains unclear. Life for Wong Kim Ark and Chinese Immigrants Prior to the Case Most Chinese immigrants came in the early 1850s from the Pearl River Delta region in China, a densely populated region that today encompasses Hong Kong, Guangzhou, and Macao1. -

1 Kenneth Burke and the Theory of Scapegoating Charles K. Bellinger Words Sometimes Play Important Roles in Human History. I

Kenneth Burke and the Theory of Scapegoating Charles K. Bellinger Words sometimes play important roles in human history. I think, for example, of Martin Luther’s use of the word grace to shatter Medieval Catholicism, or the use of democracy as a rallying cry for the American colonists in their split with England, or Karl Marx’s vision of the proletariat as a class that would end all classes. More recently, freedom has been used as a mantra by those on the political left and the political right. If a president decides to go war, with the argument that freedom will be spread in the Middle East, then we are reminded once again of the power of words in shaping human actions. This is a notion upon which Kenneth Burke placed great stress as he painted a picture of human beings as word-intoxicated, symbol-using agents whose motives ought to be understood logologically, that is, from the perspective of our use and abuse of words. In the following pages, I will argue that there is a key word that has the potential to make a large impact on human life in the future, the word scapegoat. This word is already in common use, of course, but I suggest that it is something akin to a ticking bomb in that it has untapped potential to change the way human beings think and act. This potential has two main aspects: 1) the ambiguity of the word as it is used in various contexts, and 2) the sense in which the word lies on the boundary between human self-consciousness and unself-consciousness. -

2014-2015 Report on Police Violence in the Umbrella Movement

! ! ! ! ! 2014-2015 Report on Police Violence in the Umbrella Movement A report of the State Violence Database Project in Hong Kong Compiled by The Professional Commons and Hong Kong In-Media ! ! ! Table!of!Contents! ! About!us! ! About!the!research! ! Maps!/!Glossary! ! Executive!Summary! ! 1.! Report!on!physical!injury!and!mental!trauma!...........................................................................................!13! 1.1! Physical!injury!....................................................................................................................................!13! 1.1.1! Injury!caused!by!police’s!direct!smacking,!beating!and!disperse!actions!..................................!14! 1.1.2! Excessive!use!of!force!during!the!arrest!process!.......................................................................!24! 1.1.3! Connivance!at!violence,!causing!injury!to!many!.......................................................................!28! 1.1.4! Delay!of!rescue!and!assault!on!medical!volunteers!..................................................................!33! 1.1.5! Police’s!use!of!violence!or!connivance!at!violence!against!journalists!......................................!35! 1.2! Psychological!trauma!.........................................................................................................................!39! 1.2.1! Psychological!trauma!caused!by!use!of!tear!gas!by!the!police!..................................................!39! 1.2.2! Psychological!trauma!resulting!from!violence!...........................................................................!41! -

10. Tacking Biphobia: a Guide for Safety Services

10. Tacking Biphobia: A Guide for Safety Services This information sheet provides advice for criminal justice and other safety services, such as the police, councils, charities and the Crown Prosecution Service, on biphobia and biphobic hate crime. Service providers have a responsibility to tackle prejudice and hate crime faced by bisexual people. The first section below will help them to recognise biphobia and biphobic hate crime and the second will enable them to record and deal with incidents. The final section shows the positive steps that can be taken to raise awareness of the issues and create a safe and welcoming environment for bisexual people. Section 1: Recognising and understanding biphobic hate crime What is biphobia? Biphobia is a prejudicial attitude toward bisexuality and a source of discrimination and hate crime against bisexual people, often based on negative stereotypes. It can include believing that bisexual people are: Deceitful, dangerous or perverse Greedy, promiscuous or exotic Confused, indecisive or 'going through a phase' Responsible for spreading disease Interfering with progress around lesbian and gay rights. What is biphobic hate crime? Service providers should treat any criminal offence or non-criminal incident as biphobic if the person who experienced or witnessed the incident feels it was motivated by biphobia. Biphobic hate crime can include verbal, physical or sexual abuse from the perpetrator. Because people’s bisexual identity is not always visible to strangers, biphobic abuse can often be concentrated in settings where the victim and perpetrator know each other. They could be relatives, friends or acquaintances and the hate crime could be domestic abuse or unwanted sexual touching. -

Matthew Shepard

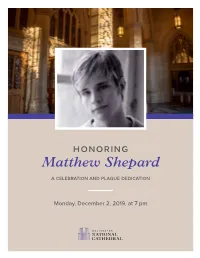

honoring Matthew Shepard A CELEBrATion AnD PLAQUE DEDiCATion Monday, December 2, 2019, at 7 pm Welcome Dean Randolph M. Hollerith, Washington National Cathedral Dennis Shepard, Matthew Shepard Foundation True Colors by Cyndi Lauper (b. 1953); arr. Deke Sharon (b. 1967) Potomac Fever, Gay Men’s Chorus of Washington, D.C. Kevin Thomason, Soloist Waving Through a Window from Dear Evan Hansen; by Benj Pasek (b. 1985) and Justin Paul (b. 1985); Potomac Fever, Gay Men’s Chorus of Washington, D.C. arr. Robert T. Boaz (1970–2019) You Raise Me Up by Brendan Graham (b. 1945) & Rolf Lovland (b. 1955) Brennan Connell, GenOUT; C. Paul Heins, piano The Laramie Project (moments) by Moises Kaufman and members of the Tectonic Theater Project St. Albans/National Cathedral School Thespian Society. Chris Snipe, Director Introduced by Dennis Shepard *This play contains adult language.* Matthew Sarah Muoio (Romaine Patterson) Homecoming Matthew Merril (Newsperson), Nico Cantrell (Narrator), Ilyas Talwar (Philip Dubois), Martin Villagra‑Riquelme (Harry Woods), Jorge Guajardo (Matt Galloway) Two Queers and a Catholic Priest Fiona Herbold (Narrator), Louisa Bayburtian (Leigh Fondakowski), William Barbee (Greg Pierotti and Father Roger Schmit) The people are invited to stand. The people’s responses are in bold. Opening Dean Randolph M. Hollerith, Washington National Cathedral God is with us. God’s love unites us. God’s purpose steadies us. God’s Spirit comforts us. PeoPle: Blessed be God forever. O God, whose days are without end, and whose mercies cannot be numbered: Make us, we pray, deeply aware of the shortness of human life. We remember before you this day our brother Matthew and all who have lost their lives to violent acts of hate. -

Don't Shoot: Race-Based Trauma and Police Brutality Leah Metzger

Taylor University Pillars at Taylor University Orphans and Vulnerable Children Student Orphans and Vulnerable Children Scholarship Spring 2019 Don't Shoot: Race-Based Trauma and Police Brutality Leah Metzger Follow this and additional works at: https://pillars.taylor.edu/ovc-student Part of the Child Psychology Commons, Higher Education Commons, and the Social Welfare Commons Running head: DON’T SHOOT 1 Don’t Shoot: Race-Based Trauma and Police Brutality Leah Metzger Taylor University DON’T SHOOT 2 Introduction With the growing conversation on police brutality against black Americans, there is an increasing need to understand the consequences this has on black children. Research is now showing that children and adults can experience race-based trauma, which can have profound effects on psychological and physical well-being, and can also impact communities as a whole. The threat and experience of police brutality and discrimination can be experienced individually or vicariously, and traumatic symptoms can vary depending on the individual. Children are especially vulnerable to the psychological and physical effects of police brutality and the threat thereof because of their developmental stages. Definitions and prevalence of police brutality will be discussed, as well as race based trauma, the effects of this trauma, and the impact on communities as a whole. Police Brutality Definitions Ambiguity surrounds the discussion on police brutality, leaving it difficult for many to establish what it actually is. For the purpose of this paper, police brutality is defined as, “a civil rights violation that occurs when a police officer acts with excessive force by using an amount of force with regards to a civilian that is more than necessary” (U.S. -

Organizations Endorsing the Equality Act

647 ORGANIZATIONS ENDORSING THE EQUALITY ACT National Organizations 9to5, National Association of Working Women Asian Americans Advancing Justice | AAJC A Better Balance Asian American Federation A. Philip Randolph Institute Asian Pacific American Labor Alliance (APALA) ACRIA Association of Flight Attendants – CWA ADAP Advocacy Association Association of Title IX Administrators - ATIXA Advocates for Youth Association of Welcoming and Affirming Baptists AFGE Athlete Ally AFL-CIO Auburn Seminary African American Ministers In Action Autistic Self Advocacy Network The AIDS Institute Avodah AIDS United BALM Ministries Alan and Leslie Chambers Foundation Bayard Rustin Liberation Initiative American Academy of HIV Medicine Bend the Arc Jewish Action American Academy of Pediatrics Black and Pink American Association for Access, EQuity and Diversity BPFNA ~ Bautistas por la PaZ American Association of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry Brethren Mennonite Council for LGBTQ Interests American Association of University Women (AAUW) Caring Across Generations American Atheists Catholics for Choice American Bar Association Center for American Progress American Civil Liberties Union Center for Black Equity American Conference of Cantors Center for Disability Rights American Counseling Association Center for Inclusivity American Federation of State, County, and Municipal Center for Inquiry Employees (AFSCME) Center for LGBTQ and Gender Studies American Federation of Teachers CenterLink: The Community of LGBT Centers American Heart Association Central Conference -

Getting Beneath the Surface: Scapegoating and the Systems Approach in a Post-Munro World Introduction the Publication of The

Getting beneath the surface: Scapegoating and the Systems Approach in a post-Munro world Introduction The publication of the Munro Review of Child Protection: Final Report (2011) was the culmination of an extensive and expansive consultation process into the current state of child protection practice across the UK. The report focused on the recurrence of serious shortcomings in social work practice and proposed an alternative system-wide shift in perspective to address these entrenched difficulties. Inter-woven throughout the report is concern about the adverse consequences of a pervasive culture of individual blame on professional practice. The report concentrates on the need to address this by reconfiguring the organisational responses to professional errors and shortcomings through the adoption of a ‘systems approach’. Despite the pre-occupation with ‘blame’ within the report there is, surprisingly, at no point an explicit reference to the dynamics and practices of ‘scapegoating’ that are so closely associated with organisational blame cultures. Equally notable is the absence of any recognition of the reasons why the dynamics of individual blame and scapegoating are so difficult to overcome or to ‘resist’. Yet this paper argues that the persistence of scapegoating is a significant impediment to the effective implementation of a systems approach as it risks distorting understanding of what has gone wrong and therefore of how to prevent it in the future. It is hard not to agree wholeheartedly with the good intentions of the developments proposed by Munro, but equally it is imperative that a realistic perspective is retained in relation to the challenges that would be faced in rolling out this new organisational agenda.