“Then, It Doesn't Matter Where They Come From”

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Osuuskauppa Peeässän 2020

OSUUSKAUPPA PEEÄSSÄN HALLINTO 2020 Vieremä S-market Sale Prisma Kiuruvesi Sonkajärvi Pyhäjärvi Sokos Emotion Parturi-kampaamo Kodin Terra Iisalmi Nina & Henri Varpaisjärvi ABC-liikennemyymälä ABC-automaatit Lapinlahti Sokos Hotels Pielavesi Nilsiä RAVINTOLAT: Rosso Keitele Amarillo Frans&Sophie Maaninka Ehta Vieremä Hurma S-market Siilinjärvi Juankoski Wanha Satama Sale Kaavi Prisma Tervo Buffa Kiuruvesi Sonkajärvi Presso Pyhäjärvi Sokos Emotion Karttula Riistavesi Hesburger Parturi-kampaamo Vesanto Kuopio Coffee House Kodin Terra Tuusniemi Apteekkari Iisalmi Nina & Henri Pikku Pietarin Pub O’Nelly’s Irish Bar Varpaisjärvi ABC-liikennemyymälä ABC-automaatit Vehmersalmi Hillside Pizza Breikki Lapinlahti Sokos Hotels Rautalampi Pielavesi Suonenjoki Nilsiä RAVINTOLAT: Rosso Keitele Amarillo Leppävirta Frans&Sophie Maaninka Ehta Heinävesi Hurma Siilinjärvi Juankoski Wanha Satama Tervo Vieremä Kaavi Buffa Presso S-market Hesburger Sale Varkaus Vesanto Karttula Kuopio Riistavesi Sonkajärvi Coffee House Prisma Kangaslampi Kiuruvesi Tuusniemi Apteekkari Sokos Pyhäjärvi Pikku Pietarin Pub Emotion O’Nelly’s Irish Bar Parturi-kampaamo Vehmersalmi Hillside Kodin Terra Iisalmi Pizza Breikki Nina & Henri Rautalampi Suonenjoki Varpaisjärvi ABC-liikennemyymälä ABC-automaatit Leppävirta Lapinlahti Sokos Hotels Heinävesi Pielavesi Nilsiä RAVINTOLAT: Rosso Keitele Amarillo Varkaus Frans&Sophie KangaslampiMaaninka Ehta Hurma Siilinjärvi Juankoski Wanha Satama Tervo Kaavi Buffa Presso Karttula Riistavesi Hesburger Vesanto Kuopio Coffee House Tuusniemi Apteekkari -

Kunnan/YT-Alueen Rooli Omistajanvaihdoksessa

Kunnan/YT-alueen rooli omistajanvaihdoksessa Maaseutujohtaja Juha Nykänen Sydän-Savon maaseutupalvelu Sydän-Savon maaseutupalvelu Kapteeninväylä 5, 70900 Toivala http://maaseutupalvelu.siilinjarv p. 044-7401263 i.fi [email protected] Kaavi, Kuopio, Leppävirta, Rautalampi, Rautavaara, Siilinjärvi, Suonenjoki, Tervo, Tuusniemi, Varkaus, Vesanto Kunnan/ YT-alueen rooli omistajanvaihdoksessa Alkukartoituskäynnit Avustus omistajanvaihdossuunnitelmien laatimiseen Maaseutuelinkeinoviranomaistehtävät Sydän-Savon maaseutupalvelu Kapteeninväylä 5, 70900 Toivala http://maaseutupalvelu.siilinjarv p. 044-7401263 i.fi [email protected] Kaavi, Kuopio, Leppävirta, Rautalampi, Rautavaara, Siilinjärvi, Suonenjoki, Tervo, Tuusniemi, Varkaus, Vesanto Alkukartoituskäynti Tavoitteena herätellä omistajanvaihdosta suunnittelevia tiloja aloittamaan prosessiin liittyvät toimenpiteet ja suunnittelu ajoissa ja parantaa sekä luopuvan että jatkavan yrittäjän henkistä ja tiedollista valmistautumista omistajanvaihdokseen Tavoitteena myös saada maatiloja joilla ei ole jatkajaa yhteistyöhön tuotantoaan jatkavien tilojen kanssa Alkukartoituskäynnillä kartoitamme maatilan tiedot, luopujan sekä jatkajan ajatukset ja toiveen sekä tarkastellaan omistajanvaihdoksen yleisiä ehtoja ja mahdollisuuksia tehdä omistajanvaihdos Ohjaus oikean asiantuntijan luokse Sydän-Savon maaseutupalvelu Kapteeninväylä 5, 70900 Toivala http://maaseutupalvelu.siilinjarv p. 044-7401263 i.fi [email protected] Kaavi, Kuopio, Leppävirta, Rautalampi, Rautavaara, -

Osuuskauppa Peeässän 2019

OSUUSKAUPPA PEEÄSSÄN HALLINTO2019 Vieremä S-market Sale Prisma Kiuruvesi Sonkajärvi Pyhäjärvi Sokos Emotion Parturi-kampaamo Kodin Terra Iisalmi Nina & Henri SuperCorner Pitkälahti Varpaisjärvi ABC-liikennemyymälä ABC-automaatit Lapinlahti Sokos Hotels Pielavesi Nilsiä RAVINTOLAT: Keitele Rosso Amarillo Maaninka Vieremä Frans&Sophie S-market Ehta Sale Siilinjärvi Juankoski Hurma Sonkajärvi Prisma Kaavi Kiuruvesi Sokos Tervo Wanha Satama Pyhäjärvi Emotion Buffa Parturi-kampaamo Karttula Riistavesi Presso Kodin Terra Vesanto Kuopio Hesburger Iisalmi Nina & Henri Tuusniemi Coffee House SuperCorner Pitkälahti Apteekkari Varpaisjärvi ABC-liikennemyymälä Pikku Pietarin Pub ABC-automaatit Vehmersalmi O’Nelly’s Irish Bar Lapinlahti Hillside Sokos Hotels Pielavesi Pizza Breikki Nilsiä Rautalampi Suonenjoki RAVINTOLAT: Keitele Rosso Amarillo Leppävirta Maaninka Frans&Sophie Ehta Heinävesi Siilinjärvi Juankoski Hurma Tervo Vieremä Kaavi Wanha Satama Buffa S-market Presso Sale Vesanto Karttula Kuopio Riistavesi Varkaus Sonkajärvi Hesburger Prisma Kiuruvesi Tuusniemi Coffee House Sokos Pyhäjärvi Kangaslampi Apteekkari Emotion Pikku Pietarin Pub Parturi-kampaamo Vehmersalmi O’Nelly’s Irish Bar Kodin Terra Iisalmi Hillside Nina & Henri Pizza Breikki SuperCorner Pitkälahti Rautalampi Suonenjoki Varpaisjärvi ABC-liikennemyymälä ABC-automaatit Leppävirta Lapinlahti Heinävesi Sokos Hotels Pielavesi Nilsiä RAVINTOLAT: Keitele Rosso Varkaus Amarillo KangaslampiMaaninka Frans&Sophie Ehta Siilinjärvi Juankoski Hurma Tervo Kaavi Wanha Satama Buffa Karttula Riistavesi -

WELL-BEING for People, Companies and the Environment Vieremä

EU-funding createses WELL-BEING for people, companies and the environment Vieremä Kiuruvesi Sonkajärvi SAVON TÄHDET SAVO STARS Iisalmi Rautavaara IN ENGLISH Lapinlahti Pielavesi Nilsiä Keitele Maaninka Siilinjärvi Juankoski Kaavi Tervo KUOPIO Vesanto Tuusniemi Dear reader, Suonenjoki Rautalampi this magazine is for you! It presents various EU-funded star projects in North Savo. Leppävirta EU-programs may seem fairly distant but their effects are shown in multiple ways in the Varkaus daily lives of almost all inhabitants of North Savo. They promote the well-being of people,e, companies and the environment. North Savo uses three funds of the EU: the European Regional Development Fund (ERDF), the European Social Fund (ESF) and the Rural Development Programme for Mainland Finland. The province has received 379 million Euros through these funds between 2007 and 2013. Funding also offers significant benefits: the state, municipalities, companies, educational and research institutes and societies canalize co-funding to the projects. Project activities have created several new jobs and companies in North Savo. In addition, thousands of employees have received up-to-date education, various companies and organizations have received new research and education equipment and municipalities have been supported through building municipal infrastructure that helps industry and trade. All this promotes employment, competitiveness, innovation and production activities. Financial support from the European Structural Funds in North Savo are granted by the Regional Council of Pohjois-Savo, the Centre for Economic Development, Transport and the Environment of North Savo and Finnvera. These organizations work in close cooperation with each other. Funding is aligned with provincial development programs. -

Loma Savossa HEINÄVESI Suomi Nähtävää &Kulttuuria >Tunnelmaa Tapahtumissa > Hyvinvointia Jaliikuntaa > •

Suomi Loma Savossa 2019 HEINÄVESI • JOROINEN • LEPPÄVIRTA • PIEKSÄMÄKI • VARKAUS Lomaile leppoisasti - suuntaa Savoon! Suomi Nähtävää & kulttuuria > Tunnelmaa tapahtumissa > Hyvinvointia ja liikuntaa > 2 2019 Loma Savossa HEINÄVESI • JOROINEN • LEPPÄVIRTA • PIEKSÄMÄKI • VARKAUS Savo kutsuu matkailijaa Tervetuloa keskelle kauneinta Savoa, puhtaan luonnon ja kirkkaiden järvialueiden äärelle! Monenlaiset mukavat tapahtumat ja kiiree- tön savolainen elämänmeno auttavat virittäytymään rentouttavaan lomatunnelmaan. Tämän esitteen myötä haluamme esitellä alueen parhaita paloja, kivoja kohteita ja tapahtumia vuonna 2019. Joroinen on perinteistä kartanoseutua ja ohittamaton kohde golfin ystävälle. Joroisten Musiikkipäivät ja Finntriathlon ovat saavuttaneet asemansa ainutlaatuisina kesätapahtumina. Heinävesi on tunnettu luostareistaan ja Heinäveden reitti kanavineen on osa suomalaista kansallismaisemaa. Kesäkuussa järjestettävät Heinäveden Musiikkipäivät tunnetaan jo valtakunnallisestikin. Leppävirta on Savon liikuntaharrastamisen keskus, eikä vähiten Vesileppiksen ansiosta. Pieksämäellä järjestetään maamme suurimpiin lukeutuva harrasteajoneuvo- tapahtuma Big Wheels. Kulttuurikeskus Poleeni tarjoaa monenlaista nähtävää ja koettavaa, uudistetut Veturitallit ja Veturitori hienon tapahtumapaikan. Varkaus on Suur-Saimaan rannalla sijaitseva Suomen kaviaaripääkau- punki, jossa voi tutustua teollisuuden ja mekaanisen musiikin kiehtovaan historiaan. Nähdään Savossa! ISTÖM Toimitus ÄR ER P K M K JULKAISIJAT JA VALOKUVAT SUUNNITTELU JA TAITTO PAINO Y I -

WELCOME to the LOCAL MUSEUM of LEPPÄVIRTA! One Numbered

WELCOME TO THE LOCAL MUSEUM OF times upset those plans for the museum. LEPPÄVIRTA! After the war the municipality of Leppävirta decided to establish the museum and gave an One numbered section in the text old granary for that purpose. describes one theme in the exhibition. Today there are more than 3000 items and Please, follow the pictures and you’ll about 7000 photos in the museum’s know you’re in the right place. collection. 2 Prehistoric times DOWNSTAIRS 1 About the museum It has been found that there were people living in Leppävirta area already in the Stone Age. First people came here probably from the areas of East and East-South Europe some 6000 years ago. The people of hunting culture gained their In Finland there are more museums per living from nature. Hunting, fishing and inhabitant than in any other country. Most collecting berries, mushrooms, nuts etc. was museums are quite small local museums like their main livelihood. In the showcase you this one. The purpose of local museums is to can find some tools made of stone that these represent local culture and ways of living. people used. In the other showcase are The museums are to collect historically and pieces of clay pots that were used to culturally valuable items, store them and preserve food. On the floor is an ancient exhibit them. By doing this the museum can model of flat-bottom rowboat. maintain and increase the knowledge of our history. The people of ancient hunting culture shared spiritual beliefs of nature as a sacred place. -

In Pursuit of the GENUINE CHRISTIAN IMAGE

In Pursuit of THE GENUINE CHRISTIAN IMAGE Erland Forsberg as a Lutheran Producer of Icons in the Fields of Culture and Religion Juha Malmisalo Academic dissertation To be publicly discussed, by permission of the Faculty of Theology of the University of Helsinki, in Auditorium XII in the Main Building of the University, on May 14, 2005, at 10 am. Helsinki 2005 1 In Pursuit of THE GENUINE CHRISTIAN IMAGE Erland Forsberg as a Lutheran Producer of Icons in the Fields of Culture and Religion Juha Malmisalo Helsinki 2005 2 ISBN 952-91-8539-1 (nid.) ISBN 952-10-2414-3 (PDF) University Printing House Helsinki 2005 3 Contents Abbreviations .......................................................................................................... 4 Abstract ................................................................................................................... 6 Preface ..................................................................................................................... 7 1. Encountering Peripheral Cultural Phenomena ......................................... 9 1.1. Forsberg’s Icon Painting in Art Sociological Analysis: Conceptual Issues and Selected Perspectives ............................................................ 9 1.2. An Adaptation of Bourdieu’s Theory of Cultural Fields .......................... 18 1.3. The Pictorial Source Material: Questions of Accessibility and Method .. 23 2. Attempts at a Field-Constitution ................................................................ 30 2.1. Educational, Social, and -

The Saima District

THE SAIMA DISTRICT SAVONLINNA-KUOPIO "THE PKftRL OF SrtIJVM" THE LEPPÄVIRTA ROUTE EDITED BY THE KUOPIO SECTION Ul' THE FINNISH TOURIST ASSOCIATION. THE SAIMA DISTRICT SAVONLINNA-KUOPIO THE LEPPÄVIRTA ROUTE EDITED BY THE KUOPIO SECTION OF THE FINNISH TOURIST ASSOCIATION PRINTED IN KUOPIO 1928 BY POHJOIS-SAVON KIRJAPAINO O.Y 2 The harbour of Savonlinna TJ*inland does not offer the foreign tourist much in the way of historic monuments or famous art treasures, but she offers so much more in the way of beautiful scenery, the peace and pleasure of which comes from being in close contact with untouched nature. The beauty of the country lies especially in the extensive forests, and in the sin- gular profusion of lakes. It is most apparent in the large lake district, and in the magnificent wa- 3 terways of Lake Saima. Here the admirer of na~ fure and the tourist receives a never to be forgot- ten impression. Here the tourist, who has visited different parts of the country may exclaim: „The chain of the Saima lakes is the most wonderful thing I have ever seen; here is the northern para- dise of hills, forests, and lakes." But as a boat trip along this chain of lakes, with its many branches extending for miles in all directions, demands too much of the tourist's pre- cious time, he must satisfy himself by experiencing the best part of all by undertaking the journey from Savonlinna via Varkaus to Kuopio, from the border of Olof's Castle to the base of the stately Puijo Hill. -

Climate Friendly Bioenergy Solutions 14.—25.9.2020

Eseia International Online Summer School Climate Friendly Bioenergy Solutions 14.—25.9.2020 Arranged by Eastern Finland Universities together with Tanzanian partners and ESEIA - network (including Project works related to promotion of cooperation between Europe and Africa in the field of climate friendly bioenergy solutions) eseia ISS 2020 Course description Organisation The student will receive comprehensive overview of environmentally friendly bioenergy solutions (by lectu- The Eseia ISS 2020 will be organized together with res and company presentations) and they will apply bioeconomy specialized universities in Eastern Finland their knowledge for preparation a proposal of adapting European environmental friendly technology in Africa. Savonia University of Applied Sciences (Varkaus, Kuopio, Iisalmi) The two week programme arranged by Eastern Finland Karelia University of Applied Sciences (Joensuu) Universities together with Tanzanian partners and University of Eastern Finland (Kuopio, Joensuu) ESEIA network consist of lectures, company presentati- ons, individual assignments, workshops, supervised group tasks and presentation group work results. Content: Introduction Presentation of challenges for students group works Orientation to project works Soil improvement and circular fertilizer products Possibilities to utilize ash as such or purified by proper processing for fertilizers and earth construc- tion materials Environmental friendly combustion technologies, (testing of emission reduction technologies with fluidized bed pilot -

Maakuntien Nimet Neljällä Kielellä (Fi-Sv-En-Ru) Ja Kuntien Nimet Suomen-, Ruotsin- Ja Englanninkielisiä Tekstejä Varten

16.1.2019 Suomen hallintorakenteeseen ja maakuntauudistukseen liittyviä termejä sekä maakuntien ja kuntien nimet fi-sv-en-(ru) Tiedosto sisältää ensin Suomen hallintorakenteeseen ja hallinnon tasoihin liittyviä termejä suomeksi, ruotsiksi ja englanniksi. Myöhemmin tiedostossa on termejä (fi-sv-en), jotka koskevat suunniteltua maakuntauudistusta. Lopuksi luetellaan maakuntien nimet neljällä kielellä (fi-sv-en-ru) ja kuntien nimet suomen-, ruotsin- ja englanninkielisiä tekstejä varten. Vastineet on pohdittu valtioneuvoston kanslian käännös- ja kielitoimialan ruotsin ja englannin kielityöryhmissä ja niitä suositetaan käytettäväksi kaikissa valtionhallinnon teksteissä. Termisuosituksiin voidaan tarvittaessa tehdä muutoksia tai täydennyksiä. Termivalintoja koskeva palaute on tervetullutta osoitteeseen termineuvonta(a)vnk.fi. Termer med anknytning till förvaltningsstrukturen i Finland och till landskapsreformen samt landskaps- och kommunnamn fi-sv-en-(ru) Först i filen finns finska, svenska och engelska termer med anknytning till förvaltningsstrukturen och förvaltningsnivåerna i Finland. Sedan följer finska, svenska och engelska termer som gäller den planerade landskapsreformen. I slutet av filen finns en fyrspråkig förteckning över landskapsnamnen (fi-sv-en-ru) och en förteckning över kommunnamnen för finska, svenska och engelska texter. Motsvarigheterna har tagits fram i svenska och engelska arbetsgrupper i översättnings- och språksektorn vid statsrådets kansli och det rekommenderas att motsvarigheterna används i statsförvaltningens texter. -

Guide for Incoming Exchange Students Welcome to Savonia

SAVONIA UNIVERSITY OF APPLIED SCIENCES Guide for incoming exchange students Welcome to Savonia International skills can be achieved only by Incoming students from abroad will be looking for: international mobility activities and by international study programmes which are relevant to their final cooperation. To be able to operate internationally degree, you need not only foreign language skills but also full academic recognition which ensures that they experiences abroad, knowledge of different cultures will not lose time in completing their degree by and ability to think in a global way. The best way to studying abroad. learn these skills is to study and work abroad. It is also very important for us to learn international skills from To help students make th most from their studies our foreign incoming students. In active interaction abroad we have European Credit Transfer System and with foreign students and their universities we will Accumulation System (ECTS), which provides a way understand better other cultures and we can see them of measuring and comparing learning achievements, as a part of increasing international development. The and transferring them from one insitutution to another. interaction between people from other countries is the most essential tool in building organizations more ECTS helps higher education institutions to enhance international. their cooperation with other institutions by: At Savonia University of Applied Sciences we try to improving access to information on curricula, increase our international cooperation. We must be able providing common procedures for academic to receive more students from abroad so we are very recognition. happy of your arrival in Savonia. -

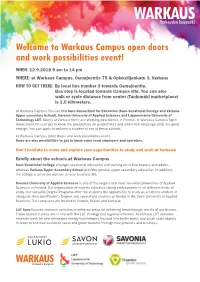

Welcome to Warkaus Campus Open Doors and Work Possibilities Event!

Welcome to Warkaus Campus open doors and work possibilities event! WHEN: 12.9.2018 9 am to 14 pm WHERE: at Warkaus Campus, Osmajoentie 75 & Opiskelijankatu 3, Varkaus HOW TO GET THERE: By local bus number 3 towards Osmajoentie. Bus stop is located towards Campus site. You can also walk or cycle distance from center (Taulumäki marketplace) is 1,5 kilometers. At Warkaus Campus You can findSavo Consortium for Education (Savo Vocational College and Varkaus Upper secondary School), Savonia University of Applied Sciences and Lappeenranta University of Technology LUT. Mainly at Varkaus there are studying possibilities in Finnish. At Warkaus Campus Open doors event You can get to know the possibilities on guided tours and when Your language skills are good enough, You can apply to become a student at any of these schools. At Warkaus Campus Open doors and work possibilities event, there are also possibilities to get to know some local employers and operators. Don’t hesitate to come and explore your opportunities to study and work at Varkaus! Briefly about the schools at Warkaus Campus Savo Vocational College arranges vocational education and training for school leavers and adults, whereas Varkaus Upper Secondary School provides general upper secondary education. In addition, the college is an active partner to local business life. Savonia University of Applied Sciences is one of the largest and most versatile Universities of Applied Sciences in Finland. Our organization of experts educates strong professionals in six different fields of study. Our versatile Degree Programs offer the students the opportunity to study as a fulltime student or alongside their job (Master’s Degree and specialized studies) or flexibly in the Open University of Applied Sciences.