Texas San Antonio Division

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Outlook for the New Congress

Outlook for the New Congress Where are we going • FY 2015 operating under CR • Omnibus Release Date – December 8 (source - House Appropriations) • Expires on December 11 • Current goal: omnibus bill • Other possibilities: CR through March 31; full year CR • FY 2015 Defense Authorization • FY 2016 budget process • Return to “regular order?” • Another budget agreement? 2 2014 Senate Results Chart The GOP takes control 3 2014 House Results Chart The GOP expands their majority 184 244 4 Senate Energy and Water Appropriations Subcommittee Democratic Subcommittee Members Republican Subcommittee Members • Dianne Feinstein (CA), Likely RM • Lamar Alexander (TN), Likely Chair • Patty Murray (WA) • Thad Cochran (MS) • Tim Johnson (SD) • Mitch McConnell (KY)* • Mary Landrieu (LA) ??? • Richard Shelby (AL) • Tom Harkin (IA) • Susan Collins (ME) • Jon Tester (MT) • Lisa Murkowski (AK) • Richard Durbin (IL) • Lindsey Graham (SC) • Tom Udall (NM) • John Hoeven (ND) • Jeanne Shaheen (NH) [Harry Reid – Possible RM] *as Majority Leader, McConnell may take a leave of absence from the Committee 5 House Energy and Water Appropriations Subcommittee Republican Subcommittee Members • Michael Simpson (ID), Chair • Rodney P. Frelinghuysen (NJ) Democratic Subcommittee • Alan Nunnelee (MS), Vice Chair Members • Ken Calvert (CA) • Marcy Kaptur (OH), RM • Chuck Fleishmann (TN) • Pete Visclosky (IN) • Tom Graves (GA) • Ed Pastor (AZ) • Jeff Fortenberry (NE) • Chaka Fattah (PA) 6 Senate Armed Services Republican Subcommittee Democratic Subcommittee Members Members -

Curriculum Vitæ

Revised August 2020 PETE P. GALLEGO PROFILE A native of Alpine and graduate of Sul Ross State University, Pete Gallego is a trained mediator with over 25 years of public service and both legal and legislative experience. Licensed to practice law in Texas since 1986, he holds a Juris Doctor degree from The University of Texas School of Law (1985) and a Bachelor's degree from Sul Ross (1982). Gallego has tried numerous civil and criminal cases during his career as a prosecutor and insurance defense attorney. Gallego comes from a local family of high achievers. His parents were the first in their families to attend college and receive degrees. One of his sisters was the first Latin/x graduate of Alpine High School to become a licensed attorney and the other to finish medical school and become a licensed physician. In 1990, Gallego also became the first Latin/x elected to the Texas House from District 74, a district containing much of the US/Mexico border. He is also the only non-Bexar County resident elected to represent Congressional District 23 since the inclusion of Bexar County to District 23 in 1980. He remains the only rural Far West Texan ever elected to serve in the US Congress. A leader, mentor and skilled fundraiser who can implement goals and provide strategic direction, Pete Gallego is accustomed to creating consensus, building and maintaining networks, and navigating complex state/federal law and procedure. His unique background would allow Sul Ross to increase its profile, expand its reach and build its success. -

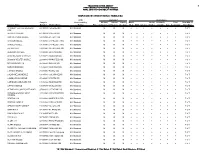

Campus Distinctions by Highest Number Met

TEXAS EDUCATION AGENCY 1 PERFORMANCE REPORTING DIVISION FINAL 2018 ACCOUNTABILITY RATINGS CAMPUS DISTINCTIONS BY HIGHEST NUMBER MET 2018 Domains* Distinctions Campus Accountability Student School Closing Read/ Social Academic Post Num Met of Campus Name Number District Name Rating Note Achievement Progress the Gaps ELA Math Science Studies Growth Gap Secondary Num Eval ACADEMY FOR TECHNOLOGY 221901010 ABILENE ISD Met Standard M M M ● ● ● ● ● ● ● 7 of 7 ENG ALICIA R CHACON 071905138 YSLETA ISD Met Standard M M M ● ● ● ● ● ● ● 7 of 7 ANN RICHARDS MIDDLE 108912045 LA JOYA ISD Met Standard M M M ● ● ● ● ● ● ● 7 of 7 ARAGON MIDDLE 101907051 CYPRESS-FAIRB Met Standard M M M ● ● ● ● ● ● ● 7 of 7 ARNOLD MIDDLE 101907041 CYPRESS-FAIRB Met Standard M M M ● ● ● ● ● ● ● 7 of 7 B L GRAY J H 108911041 SHARYLAND ISD Met Standard M M M ● ● ● ● ● ● ● 7 of 7 BENJAMIN SCHOOL 138904001 BENJAMIN ISD Met Standard M M M ● ● ● ● ● ● ● 7 of 7 BRIARMEADOW CHARTER 101912344 HOUSTON ISD Met Standard M M M ● ● ● ● ● ● ● 7 of 7 BROOKS WESTER MIDDLE 220908043 MANSFIELD ISD Met Standard M M M ● ● ● ● ● ● ● 7 of 7 BRYAN ADAMS H S 057905001 DALLAS ISD Met Standard M M M ● ● ● ● ● ● ● 7 of 7 BURBANK MIDDLE 101912043 HOUSTON ISD Met Standard M M M ● ● ● ● ● ● ● 7 of 7 C M RICE MIDDLE 043910053 PLANO ISD Met Standard M M M ● ● ● ● ● ● ● 7 of 7 CALVIN NELMS MIDDLE 101837041 CALVIN NELMS Met Standard M M M ● ● ● ● ● ● ● 7 of 7 CAMINO REAL MIDDLE 071905051 YSLETA ISD Met Standard M M M ● ● ● ● ● ● ● 7 of 7 CARNEGIE VANGUARD H S 101912322 HOUSTON ISD Met Standard M M M ● ● ● -

Distinction Designations

TEXAS EDUCATION AGENCY 1 PERFORMANCE REPORTING DIVISION FINAL 2018 ACCOUNTABILITY RATINGS DISTRICTS AND CAMPUSES RECEIVING ONE OR MORE DISTINCTIONS BY DISTRICT NAME District/ 2018 Domains* Distinctions Campus Accountability Student School Closing Read/ Social Academic Post Num Met of District/Campus Name Number Rating Note Achievement Progress the Gaps ELA Math Science Studies Growth Gap Secondary Num Eval A W BROWN LEADERSHIP 057816 C ACADEMY AW BROWN-F L A INT CAMPUS 101 Met Standard I M M ○ ○ ○ ○ ● ○ ○ 1 of 7 A+ ACADEMY 057829 C A+ SECONDARY SCHOOL 002 Met Standard M M M ● ● ○ ○ ● ○ ○ 3 of 7 ABERNATHY ISD 095901 B ABERNATHY H S 001 Met Standard M M M ○ ● ● ● ● ● ● 6 of 7 ABERNATHY EL 101 Met Standard M M M ○ ○ ○ ● ● ○ 2 of 6 ABILENE ISD 221901 B ABILENE H S 001 Met Standard M M M ○ ● ○ ● ○ ● ● 4 of 7 COOPER H S 002 Met Standard M M M ● ● ● ● ○ ● ● 6 of 7 ACADEMY FOR TECHNOLOGY 010 Met Standard M M M ● ● ● ● ● ● ● 7 of 7 ENG CLACK MIDDLE 047 Met Standard M M M ○ ○ ● ○ ○ ○ ● 2 of 7 CRAIG MIDDLE 048 Met Standard M M M ○ ○ ○ ● ○ ○ ○ 1 of 7 AUSTIN EL 102 Met Standard M M M ● ○ ● ● ● ○ 4 of 6 BOWIE EL 104 Met Standard M M M ○ ○ ● ○ ○ ● 2 of 6 DYESS EL 108 Met Standard M M M ● ● ○ ○ ● ● 4 of 6 JACKSON EL 112 Met Standard M M M ● ○ ● ○ ● ● 4 of 6 TAYLOR EL 121 Met Standard M M M ○ ○ ● ○ ○ ○ 1 of 6 THOMAS EL 151 Met Standard M M M ● ● ● ● ● ● 6 of 6 BASSETTI EL 153 Met Standard M M M ● ○ ○ ○ ● ● 3 of 6 MARTINEZ EL 155 Met Standard M M M ○ ● ○ ○ ○ ● 2 of 6 ACADEMY ISD 014901 B ACADEMY J H 041 Met Standard M M M ○ ○ ○ ● ○ ○ ○ 1 of 7 ACADEMY INT -

Board Members, Assistant Superintendents, Business Managers, and Public Education Information Management System (PEIMS) Coordinators, March 2020

Texas Public School Districts and Charters: Board Members, Assistant Superintendents, Business Managers, and Public Education Information Management System (PEIMS) Coordinators, March 2020 Texas School Directory, 2019-20 243 244 Texas School Directory, 2019-20 Texas Public School Districts and Charters: Board Members, Assistant Superintendents, Business Managers, and Public Education Information Management System (PEIMS) Coordinators, March 2020 001 ANDERSON COUNTY KYLE PENN ..................................................... CFO/BUSINESS MANAGER 001-909 SLOCUM ISD 001-902 CAYUGA ISD DANIEL BAILEY ............................................... BOARD PRESIDENT TIM WEST ....................................................... BOARD PRESIDENT STEVE WEBB .................................................. BOARD VICE-PRESIDENT JESSICA MCCANN ......................................... BOARD VICE-PRESIDENT JOHN DAY ...................................................... BOARD SECRETARY TAMMY LIGHTFOOT ....................................... BOARD SECRETARY JOHN BARTON ............................................... BOARD MEMBER JOHN KELLEY ................................................. BOARD ASSISTANT SECRETARY DARRIN FARLEY ............................................. BOARD MEMBER SCOTT COTTON ............................................. BOARD MEMBER DAVID HART ................................................... BOARD MEMBER DONALD LOVING ............................................. BOARD MEMBER BEN MISSILDINE ............................................ -

Texas BOMA Legislative Update by Robert D. Miller, Yuniedth Midence Steen, and Gardner Pate November 7, 2012 the Elections

Texas BOMA Legislative Update by Robert D. Miller, Yuniedth Midence Steen, and Gardner Pate November 7, 2012 The elections are (finally) over! Last night, across the country, voters chose not just the President, but also members of the U.S. Senate, Congress, and various state and local races. Texas was no different. The Presidential Race President Barack Obama (D) defeated former Governor Mitt Romney (R) in the race for President. President Obama won at least 303 electoral votes (at the time of writing, Florida has not yet been called for either candidate) to Governor Romney’s 206, putting the President above the required number of 270 needed to win the election. Federal Races Despite the literally billions of dollars spent this election cycle on congressional and U.S. senate races, very little changed in the grand scheme of things. In the U.S. Senate, Democrats will have 55 seats to the Republicans 45, a net pickup of 2 seats for Democrats and a corresponding net loss of 2 seats for the Republicans. In the U.S. House, while a few races are still outstanding, Republicans will comfortably maintain their majority. In Texas, former solicitor general Ted Cruz (R) handily defeated former Rep. Paul Sadler (D) to become the next U.S. Senator from Texas, replacing retiring Sen. Kay Bailey Hutchison (R). After the 2011 census, Texas added four new congressional districts, expanding the delegation from 32 to 36. In 2013, the Texas partisan breakdown will be 24 Republicans and 12 Democrats, a change from the current 23-9 split. Next year, four members of the 2011 delegation will not return to Congress: Quico Canseco* (R-San Antonio), Charlie Gonzalez (D- San Antonio), Ron Paul (R-Surfside), and Silvestre Reyes (D-El Paso). -

Clean Water Act NPDES Permit Impacts on Mo

KEY COMMITTEES IN THE SENATE Senate Committee on Environment and Public Works Issues: Clean Water Act NPDES Permit Impacts on Mosquito Control Programs Endangered Species Act Considerations and Mosquito Control Mosquito Control on National Wildlife Refuges and Other Federal Lands Boxer, Barbara (CA) , Chairman Vitter, David (LA), Ranking Member Baucus, Max (MT) Inhofe, James M. (OK) Carper, Thomas R. (DE) Barrasso, John (WY) Lautenberg, Frank R. (NJ) Sessions, Jeff (AL) Cardin, Benjamin L. (MD) Crapo, Mike (ID) Sanders, Bernard (VT) Wicker, Roger F. (MS) Whitehouse, Sheldon (RI) Boozman, John (AR) Udall, Tom (NM) Fischer, Deb (NE Merkley, Jeff (OR) Gillibrand, Kirsten E. (NY) Highlighted = members of the Subcommittee on Water and Wildlife which oversees the Clean Water Act, Endangered Species Act, and National Wildlife Refuges Senate Committee on Agriculture, Nutrition and Forestry Issue: Clean Water Act NPDES Permit Impacts on Mosquito Control Programs Stabenow, Debbie (MI) , Chairman Cochran, Thad (MS), Ranking Member Leahy, Patrick J. (VT) McConnell, Mitch (KY) Harkin, Tom (IA) Roberts, Pat (KS) Baucus, Max (MT) Chambliss, Saxby (GA) Brown, Sherrod (OH) Boozman, John (AR) Klobuchar, Amy (MN) Hoeven, John (ND) Bennet, Michael F. (CO) Johanns, Mike (NE) Gillibrand, Kirsten E. (NY) Grassley, Chuck (IA) Donnelly, Joe (IN) Thune, John (SD) Heitkamp, Heidi (ND) Cowan, William M. (MA) Highlighted = members of the Subcommittee on Conservation, Forestry, and Natural Resources which oversees pesticides Senate Committee on Energy and Natural Resources Issue: Mosquito Control on National Wildlife Refuges and Other Federal Lands Wyden, Ron (OR) , Chairman Murkowski, Lisa (AK), Ranking Member Johnson, Tim (SD) Barrasso, John (WY)* Landrieu, Mary L. -

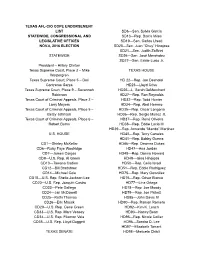

Texas Aflcio Cope Endorsement List Statewide, Congressional and Legislative Offices Nov.8, 2016

TEXAS AFLCIO COPE ENDORSEMENT LIST SD6—Sen. Sylvia Garcia STATEWIDE, CONGRESSIONAL AND SD13—Rep. Borris Miles LEGISLATIVE OFFICES SD19—Sen. Carlos Uresti NOV.8, 2016 ELECTION SD20—Sen. Juan “Chuy” Hinojosa SD21—Sen. Judith Zaffirini STATEWIDE SD26—Sen. José Menéndez SD27—Sen. Eddie Lucio Jr. President – Hillary Clinton Texas Supreme Court, Place 3 – Mike TEXAS HOUSE Westergren Texas Supreme Court, Place 5 – Dori HD 22—Rep. Joe Deshotel Contreras Garza HD23—Lloyd Criss Texas Supreme Court, Place 9 – Savannah HD26—L. Sarah DeMerchant Robinson HD27—Rep. Ron Reynolds Texas Court of Criminal Appeals, Place 2 – HD32—Rep. Todd Hunter Larry Meyers HD34—Rep. Abel Herrero Texas Court of Criminal Appeals, Place 5 – HD35—Rep. Oscar Longoria Betsy Johnson HD36—Rep. Sergio Munoz Jr. Texas Court of Criminal Appeals, Place 6 – HD37—Rep. René Oliveira Robert Burns HD38—Rep. Eddie Lucio III HD39—Rep. Armando “Mando” Martinez U.S. HOUSE HD40—Rep. Terry Canales HD41—Rep. Bobby Guerra CD1—Shirley McKellar HD46—Rep. Dawnna Dukes CD6—Ruby Faye Woolridge HD47—Ana Jordan CD7—James Cargas HD48—Rep. Donna Howard CD9—U.S. Rep. Al Green HD49—Gina Hinojosa CD10—Tawana Cadien HD50—Rep. Celia Israel CD12—Bill Bradshaw HD51—Rep. Eddie Rodriguez CD14—Michael Cole HD75—Rep. Mary González CD18—U.S. Rep. Sheila Jackson Lee HD76—Rep. César Blanco CD20—U.S. Rep. Joaquin Castro HD77—Lina Ortega CD23—Pete Gallego HD78—Rep. Joe Moody CD24—Jan McDowell HD79—Rep. Joe Pickett CD25—Kathi Thomas HD85—John Davis IV CD26—Eric Mauck HD90—Rep. Ramon Romero CD29—U.S. -

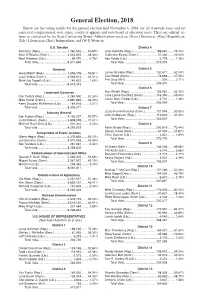

General Election, 2018

General Election, 2018 Below are the voting results for the general election held November 6, 2018, for all statewide races and for contested congressional, state senate, courts of appeals and state board of education races. These are official re- turns as canvassed by the State Canvassing Board. Abbreviations used are (Dem.) Democrat, (Rep.) Republican, (Lib.) Libertarian, (Ind.) Independent, and (W-I) Write-in. U.S. Senator District 4 Ted Cruz (Rep.) ............................... 4,260,553 ....... 50.89% John Ratcliffe (Rep.) ........................... 188,667 ....... 75.70% Beto O’Rourke (Dem.) ..................... 4,045,632 ....... 48.33% Catherine Krantz (Dem.)....................... 57,400 ....... 23.03% Neal Dikeman (Lib.) .............................. 65,470 ......... 0.78% Ken Ashby (Lib.) ..................................... 3,178 ......... 1.28% Total Vote .................................. 8,371,655 Total Vote ..................................... 249,245 Govenor District 5 Greg Abbott (Rep.) .......................... 4,656,196 ....... 55.81% Lance Gooden (Rep.) ......................... 130,617 ....... 62.34% Lupe Valdez (Dem.) ......................... 3,546,615 ....... 42.51% Dan Wood (Dem.) ................................. 78,666 ....... 37.55% Mark Jay Tippetts (Lib.) ...................... 140,632 ......... 1.69% Phil Gray (W-I) ........................................... 224 ......... 0.11% Total vote ................................... 8,343,443 Total Vote ..................................... 209,507 District -

December 6, 2011 Annual Members Only Holiday Roundtable

November 2011 Arizona Industry Liaison Group Affiliate November 15, 2011 Inside this issue: Conference Agenda 2 14th Annual Compliance Conference Conference Topics & Speaker 3-8 Profiles OFCCP Regulatory Update 3 Marvin Jordan, OFCCP Theresa Lujan, OFCCP The Blueprint (Case Studies 4 In this month’s Newsletter we profile in Effective Compliance) the speakers and topics for our Greta Young, OFCCP 14th Annual Compliance Conference. The Spirit of Inclusion 5 (Panel Discussion with Community-Based Organizations) See the complete agenda on page 2. Greg Smith, OFCCP Cody Cummings, OFCCP Developing an 6 Effective OFCCP Job Register online at www.azquada.org Listing Compliance Program Rathin Sinha, America’s or Job Exchange EEOC Legal Update 7 To register by check, use the Mary Jo O’Neill, EEOC registration form found on page 2. Systemic Litigation/ 8 Investigation (Panel Discussion) OFCCP & EEOC Articles 9-12 December 6, 2011 Annual Members Only Holiday Roundtable TIME: 8:30-11:30 a.m. LOCATION: APS, 400 N. 5th Street, Phoenix COST: FREE for Members $75 for Nonmembers (includes 2012 membership Please RSVP by Friday, December 2 to [email protected] 14th Annual Compliance Conference November 15, 2011 Desert Willow Conference Center 4340 E. Cotton Center Blvd #100, Phoenix, AZ 7:00 Registration 11:00 Developing an Effective OFCCP Job Listing Compliance Program 8:00 Welcoming Remarks Rathin Sinha, President John Garza, President, Quad A America’s Job Exchange Chair, Arizona Industry Liaison Group 12:00 LUNCH 8:05 OFCCP Regulatory Update 1:15 TBA Marvin -

The Fellows of the American Bar Foundation

THE FELLOWS OF THE AMERICAN BAR FOUNDATION 2013 2013-2014 Fellows Officers: Chair Don Slesnick Chair – Elect Kathleen J. Hopkins Secretary Open The Fellows is an honorary organization of attorneys, judges and law professors whose professional, public and private careers have demonstrated outstanding dedication to the welfare of their communities and to the highest principles of the legal profession. Established in 1955, The Fellows encourage and support the research program of the American Bar Foundation. The American Bar Foundation works to advance justice through research on law, legal institutions, and legal processes. Current research covers such topics as access to justice, diversity in the legal profession, parental incarceration and its effects on children, how global norms are produced for international trade law, African Americans’ participation in law at the local level from the Civil War to the beginnings of the modern civil rights movement, lawyers’ political mobilization in the Chinese criminal justice system, end of life decision-making, and investment in early childhood education. The Fellows of the American Bar Foundation 750 N. Lake Shore Drive, 4th Floor Chicago, IL 60611 (800) 292-5065 Fax: (312) 564-8910 [email protected] www.americanbarfoundation.org OFFICERS AND DIRECTORS OF THE OFFICERS OF THE FELLOWS AMERICAN BAR FOUNDATION Don Slesnick, Chair Hon. Bernice B. Donald, President Slesnick & Casey LLP David A. Collins, Vice-President 2701 Ponce De Leon Boulevard, Suite 200 George S. Frazza, Treasurer Coral Gables, FL 33134-6041 Ellen J. Flannery, Secretary Office: (305) 448-5672 Robert L. Nelson, ABF Director [email protected] Susan Frelich Appleton Jimmy K. Goodman Kathleen J. -

House Committee on Business and Industry December 2012

Interim Report to the 83rd Texas Legislature House Committee on BUSINESS AND INDUSTRY December 2012 HOUSE COMMITTEE ON BUSINESS & INDUSTRY TEXAS HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES INTERIM REPORT 2012 A REPORT TO THE HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES 83RD TEXAS LEGISLATURE JOSEPH "JOE" DESHOTEL CHAIRMAN COMMITTEE CLERK MELISSA QUEVEDO Committee On BUSINESS & INDUSTRY December 18, 2012 JOSEPH "JOE" DESHOTEL P.O. Box 2910 Chairman Austin, Texas 78768-2910 The Honorable Joe Straus Speaker, Texas House of Representatives Members of the Texas House of Representatives Texas State Capitol, Rm. 2W.13 Austin, Texas 78701 Dear Mr. Speaker and Fellow Members: The Committee on BUSINESS & INDUSTRY of the Eighty-second Legislature hereby submits its interim report including recommendations and drafted legislation for consideration by the Eighty-third Legislature. Respectfully submitted, _______________________ JOSEPH "JOE" DESHOTEL _______________________ _______________________ ROB ORR SID MILLER _______________________ _______________________ DWAYNE BOHAC CHENTE QUINTANILLA _______________________ _______________________ JOHN V. GARZA BURT R. SOLOMONS _______________________ _______________________ HELEN GIDDINGS PAUL WORKMAN Rob Orr Vice-Chairman Members: Dwayne Bohac, John V. Garza, Helen Giddings, Sid Miller, Chente Quintanilla, Burt R. Solomons, Paul Workman TABLE OF CONTENTS INTRODUCTION .......................................................................................................................... 4 INTERIM STUDY CHARGES .....................................................................................................