Non-Compositional and Non-Hierarchical”: Rasheed Araeen’S Search for the Conceptual and the Political in British Sculpture

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Representation of National Heroes in English Language Textbooks Taught at Government Higher Secondary Schools of Sindh, Pakistan

Education and Linguistics Research ISSN 2377-1356 2018, Vol. 4, No. 2 Representation of National Heroes in English Language Textbooks Taught at Government Higher Secondary Schools of Sindh, Pakistan Abdul Razaque Lanjwan Jat English Language Development Centre, Mehran University of Engineering & Technology, Jamshoro, Pakistan Habibullah Pathan English Language Development Centre, Mehran University of Engineering & Technology, Jamshoro, Pakistan Syed Waqar Ali Shah English Language Development Centre, Mehran University of Engineering & Technology, Jamshoro, Pakistan Received: July 7, 2018 Accepted: September 4, 2018 Published: September 6, 2018 doi:10.5296/elr.v4i2.13612 URL: https://doi.org/10.5296/elr.v4i2.13612 Abstract Textbooks are not only to read but also inculcate values, virtues and norms of society given in the curriculum. Basically, the curriculum of Pakistani curriculum is broadly based on celebration of history that is taught in different subjects such as, Islamic studies, social studies, languages and Pakistan studies. These all textbooks have been used as a tool to propagate and promote national identity while representing stories of national heroes. These heroes carry certain hidden and intended ideologies. The aim of this research is to explore the textual and visual representation of national heroes of Pakistan who are portrayed in English language textbooks prescribed by Sindh Textbook Board taught in public higher secondary schools. Furthermore, this paper discusses the different elements such as; language, theme, writer’s objectivity, use of visuals, and certain ideas in order to explore the hidden ideologies behind representing national heroes. They make students patriotic, nationalistic, militaristic and religious which cause manipulation and exploitation of religion, misinterpretation and 25 http://elr.macrothink.org Education and Linguistics Research ISSN 2377-1356 2018, Vol. -

Muslim Nationalism, State Formation and Legal Representations of the Ahmadiyya Community in Pakistan

Politics of Exclusion: Muslim Nationalism, State Formation and Legal Representations of the Ahmadiyya Community in Pakistan by Sadia Saeed A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy (Sociology) in The University of Michigan 2010 Doctoral Committee: Professor George P. Steinmetz, Chair Professor Howard A. Kimeldorf Associate Professor Fatma Muge Gocek Associate Professor Genevieve Zubrzycki Professor Mamadou Diouf, Columbia University © Sadia Saeed 2010 2 Dedication This dissertation is dedicated to my parents with my deepest love, respect and gratitude for the innumerable ways they have supported my work and choices. ii Acknowledgements I would like to begin by acknowledging the immense support my parents have given me every step of the way during my (near) decade in graduate school. I have dedicated this dissertation to them. My ammi and baba have always believed in my capabilities to accomplish not only this dissertation but much more in life and their words of love and encouragement have continuously given me the strength and the will to give my research my very best. My father‘s great enthusiasm for this project, his intellectual input and his practical help and advice during the fieldwork of this project have been formative to this project. I would like to thank my dissertation advisor George Steinmetz for the many engaged conversations about theory and methods, for always pushing me to take my work to the next level and above all for teaching me to recognize and avoid sloppiness, caricatures and short-cuts. It is to him that I owe my greatest intellectual debt. -

Dissertatie Cvanwinkel

UvA-DARE (Digital Academic Repository) During the exhibition the gallery will be closed: contemporary art and the paradoxes of conceptualism van Winkel, C.H. Publication date 2012 Link to publication Citation for published version (APA): van Winkel, C. H. (2012). During the exhibition the gallery will be closed: contemporary art and the paradoxes of conceptualism. Valiz uitgeverij. General rights It is not permitted to download or to forward/distribute the text or part of it without the consent of the author(s) and/or copyright holder(s), other than for strictly personal, individual use, unless the work is under an open content license (like Creative Commons). Disclaimer/Complaints regulations If you believe that digital publication of certain material infringes any of your rights or (privacy) interests, please let the Library know, stating your reasons. In case of a legitimate complaint, the Library will make the material inaccessible and/or remove it from the website. Please Ask the Library: https://uba.uva.nl/en/contact, or a letter to: Library of the University of Amsterdam, Secretariat, Singel 425, 1012 WP Amsterdam, The Netherlands. You will be contacted as soon as possible. UvA-DARE is a service provided by the library of the University of Amsterdam (https://dare.uva.nl) Download date:03 Oct 2021 7 Introduction: During the Exhibition the Gallery Will Be Closed • 1. RESEARCH PARAMETERS This thesis aims to be an original contribution to the critical evaluation of conceptual art (1965-75). It addresses the following questions: What -

The Overseas Chevron Controversy and Canadian Identity in the Great War

Canadian Military History Volume 20 Issue 3 Article 5 2011 Side-Steppers and Original-Firsts: The Overseas Chevron Controversy and Canadian Identity in the Great War Andrew Iarocci Follow this and additional works at: https://scholars.wlu.ca/cmh Part of the Military History Commons Recommended Citation Iarocci, Andrew "Side-Steppers and Original-Firsts: The Overseas Chevron Controversy and Canadian Identity in the Great War." Canadian Military History 20, 3 (2011) This Canadian War Museum is brought to you for free and open access by Scholars Commons @ Laurier. It has been accepted for inclusion in Canadian Military History by an authorized editor of Scholars Commons @ Laurier. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Iarocci: Side-Steppers and Original-Firsts Side-Steppers and Original-Firsts The Overseas Chevron Controversy and Canadian Identity in the Great War Andrew Iarocci he Great War was more than Canadians were killed or wounded auxiliaries who had served overseas Tthree years old by the end of at Vimy between 9 and 14 April.1 for extended periods. 1917 and there was no end in sight. The Dominion of Canada, with fewer In the context of a global conflict From the Allied perspective 1917 than 8 million people, would need to that claimed millions of lives and had been an especially difficult year impose conscription if its forces were changed the geo-political landscape with few hopeful moments. On the to be maintained at fighting strength. of the modern world, it may seem Western Front, French General Robert In the meantime, heavy fighting trifling to devote an article to a Nivelle’s grand plans for victory had continued in Artois throughout simple military badge that did not failed with heavy losses, precipitating the summer of 1917. -

National Symbols of Pakistan | Pakistan General Knowledge

National Symbols of Pakistan | Pakistan General Knowledge Nation’s Motto of Pakistan The scroll supporting the shield contains Muhammad Ali Jinnah’s motto in Urdu, which reads as “Iman, Ittehad, Nazm” translated as “Faith, Unity, Discipline” and are intended as the guiding principles for Pakistan. Official Map of Pakistan Official Map of Pakistan is that which was prepared by Mahmood Alam Suhrawardy National Symbol of Pakistan Star and crescent is a National symbol. The star and crescent symbol was the emblem of the Ottoman Empire in the 19th century, and gradually became associated with Islam in late 19th-century Orientalism. National Epic of Pakistan The Hamza Nama or Dastan-e-Amir Hamza narrates the legendary exploits of Amir Hamza, an uncle of the Prophet Muhammad, though most of the stories are extremely fanciful, “a continuous series of romantic interludes, threatening events, narrow escapes, and violent acts National Calendar of Pakistan Fasli which means (harvest) is derived from the Arabic term for division, which in India was applied to the groupings of the seasons. Fasli Calendar is a chronological system introduced by the Mughal emperor Akbar basically for land revenue and records purposes in northern India. Fasli year means period of 12 months from July to Downloaded from www.csstimes.pk | 1 National Symbols of Pakistan | Pakistan General Knowledge June. National Reptile of Pakistan The mugger crocodile also called the Indian, Indus, Persian, Sindhu, marsh crocodile or simply mugger, is found throughout the Indian subcontinent and the surrounding countries, like Pakistan where the Indus crocodile is the national reptile of Pakistan National Mammal of Pakistan The Indus river dolphin is a subspecies of freshwater river dolphin found in the Indus river (and its Beas and Sutlej tributaries) of India and Pakistan. -

Political Role of Religious Communities in Pakistan

Political Role of Religious Communities in Pakistan Pervaiz Iqbal Cheema Maqsudul Hasan Nuri Muneer Mahmud Khalid Hussain Editors ASIA PAPER November 2008 Political Role of Religious Communities in Pakistan Papers from a Conference Organized by Islamabad Policy Research Institute (IPRI) and the Institute of Security and Development Policy (ISDP) in Islamabad, October 29-30, 2007 Pervaiz Iqbal Cheema Maqsudul Hasan Nuri Muneer Mahmud Khalid Hussain Editors © Institute for Security and Development Policy Västra Finnbodavägen 2, 131 30 Stockholm-Nacka, Sweden Islamabad Policy Research Institute House no.2, Street no.15, Margalla Road, Sector F-7/2, Islamabad, Pakistan www.isdp.eu; www.ipripak.org "Political Role of Religious Communities in Pakistan" is an Asia Paper published by the Institute for Security and Development Policy. The Asia Papers Series is the Occasional Paper series of the Institute’s Asia Program, and addresses topical and timely subjects. The Institute is based in Stockholm, Sweden, and cooperates closely with research centers worldwide. Through its Silk Road Studies Program, the Institute runs a joint Transatlantic Research and Policy Center with the Central Asia-Caucasus Institute of Johns Hopkins University’s School of Advanced International Studies. The Institute is firmly established as a leading research and policy center, serving a large and diverse community of analysts, scholars, policy-watchers, business leaders, and journalists. It is at the forefront of research on issues of conflict, security, and development. Through its applied research, publications, research cooperation, public lectures, and seminars, it functions as a focal point for academic, policy, and public discussion. This report is published by the Islamabad Policy Research Institute (IPRI) and is issued in the Asia Paper Series with the permission of IPRI. -

Religious Experience and Symbols of Presence Amongst the People of Eastern James Bay

RELIGIOUS EXPERIENCE AND SYMBOLS OF PRESENCE AMONGST THE PEOPLE OF EASTERN JAMES BAY Jennifer Mary Davis Faculty of Religious Studies McGill University Montreal December 2007 A thesis submitted to the Faculty of Graduate Studies and Research in partial fulfilment of the requirements of the degree of Doctor of Philosophy © Jennifer Mary Davis 2007 ii Abstract This study enquires into the relationship between cultural symbolism and religious behaviour in the development of a hunting and gathering society, the Cree of Eastern James Bay. Charles Taylor in Sources of the Self (1989) suggests that an individual’s cultural framework is apt to inform the perception of an alternate paradigm. He argues that in order to evaluate adequately such an alternate paradigm the framework from which judgements are made needs to be identified and understood. This study offers a review of Taylor’s ideas associated with identity. At the beginning of each chapter the pertinent areas of Taylor’s discussion are put forward as a context for research. From the geographical, topographical and linguistic data an analysis of how the environment is perceived by the people themselves is provided. The symbols used arise from the interaction between the people and the environment and call for a detailed analysis of the relationship between the activity of hunting and the celebration of that activity in the community ceremony known as Walking-Out (Wiiwiitahaausuunaanuu). The ceremony is aimed at initiating the young and at developing character. In the interrelationship between all aspects of the environment, individual and communal character is developed in conjunction with a rich spiritual symbolism which forms the basis of religious expression in every dimension of Eastern Cree life. -

Heraldic Terms

HERALDIC TERMS The following terms, and their definitions, are used in heraldry. Some terms and practices were used in period real-world heraldry only. Some terms and practices are used in modern real-world heraldry only. Other terms and practices are used in SCA heraldry only. Most are used in both real-world and SCA heraldry. All are presented here as an aid to heraldic research and education. A LA CUISSE, A LA QUISE - at the thigh ABAISED, ABAISSÉ, ABASED - a charge or element depicted lower than its normal position ABATEMENTS - marks of disgrace placed on the shield of an offender of the law. There are extreme few records of such being employed, and then only noted in rolls. (As who would display their device if it had an abatement on it?) ABISME - a minor charge in the center of the shield drawn smaller than usual ABOUTÉ - end to end ABOVE - an ambiguous term which should be avoided in blazon. Generally, two charges one of which is above the other on the field can be blazoned better as "in pale an X and a Y" or "an A and in chief a B". See atop, ensigned. ABYSS - a minor charge in the center of the shield drawn smaller than usual ACCOLLÉ - (1) two shields side-by-side, sometimes united by their bottom tips overlapping or being connected to each other by their sides; (2) an animal with a crown, collar or other item around its neck; (3) keys, weapons or other implements placed saltirewise behind the shield in a heraldic display. -

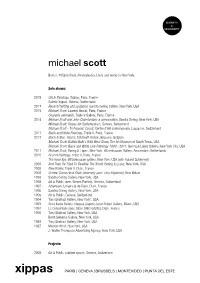

Michael Scott

BIOGRAPHY & BIBLIOGRAPHY michael scott Born in 1958 in Paoli, Pennsylvania. Lives and works in New York. Solo shows: 2018 Circle Paintings, Xippas, Paris, France Galerie Xippas, Geneva, Switzerland 2017 Recent Painting and sculpture, Sandra Gering Gallery, New York, USA 2015 Michael Scott, Laurent Strouk, Paris, France Courants alternatifs, Triple V Gallery, Paris, France 2014 Michael Scott and John Chamberlain: a conversation, Sandra Gering, New York, USA Michael Scott, Xippas Art Contemporain, Geneva, Switzerland Michael Scott - To Present, Circuit, Centre d’Art contemporain, Lausanne, Switzerland 2013 Black and White Paintings, Triple V, Paris, France 2012 Black & Blue, Galerie Odermatt-Vedovi, Brussels, Belgium Michael Scott: Buffalo Bulb’s Wild West Show, The Art Museum of South Texas, USA Michael Scott: Black and White Line Paintings 1989 - 2011, Gering & López Gallery, New York City, USA 2011 Michael Scott, Gering & López, New York, Witzenhausen Gallery, Amsterdam, Netherlands 2010 Recent Paintings, Triple V, Paris, France The Inner Eye, Witzenhausen gallery, New York, USA (with Roland Schimmel) 2009 And Then He Tried To Swallow The World, Gering & Lopez, New York, USA 2008 New Works, Triple V, Dijon, France 2002 Central Connecticut State University (avec Toby Kilpatrick), New Britain 1999 Sandra Gering Gallery, New York, USA 1998 Art & Public (avec Steven Parrino), Geneva, Switzerland 1997 Atheneum, Université de Dijon, Dijon, France 1996 Sandra Gering Gallery, New York, USA 1995 Art & Public, Geneva, Switzerland 1994 Tony Shafrazi Gallery, New York*, USA 1993 Akira Ikeda Gallery, Nagoya (Japon) Jason Rubell Gallery, Miami, USA 1991 Le Consortium (avec Steve DiBenedetto), Dijon, France 1990 Tony Shafrazi Gallery, New York, USA Brent Sikkema Gallery, New York, USA 1989 Tony Shafrazi Gallery, New York, USA 1987 Mission West, New York, USA J. -

The Dialogical Imagination: the Conversational Aesthetic of Conceptual Art

THE DIALOGICAL IMAGINATION: THE CONVERSATIONAL AESTHETIC OF CONCEPTUAL ART MICHAEL CORRIS Within the history of avant-garde art there is a recurrent interest in process-based practices. A substantial claim made by proponents of this position argues that process-based practices offer far more scope for the revision of the conventional culture of art than any other type of practice. In the first place, process-based practices dispense with the idea of the production of a material object as the principle aim of art. While there is often a material ‘residue’ associated with process- based art, its status as an autonomous object of art is always questionable. Such objects are more properly understood as props or by-products, and are valued accordingly by the artist (but not, alas, by the critic, curator or collector). Process-based practices themselves raise difficult questions for connoisseurs; there is often no clear notion where to locate the boundary dividing process works from the environment at large. The process-based work of art may not result in an object at all; rather, it could be a performance (scripted or not), an environment or installation, an intervention in a public space, or some sort of social encounter, such as a conversation or an on-going project with a community. The point of all these practices is to radically alter the subject-position of both artist and beholder. By so doing, the very idea of the autonomy of art is placed in question. Once attention and purpose are shifted from the making of what amounts to medium- sized dry goods, so the argument goes, both artist and spectator are liberated. -

Conceptual Art: a Critical Anthology

Conceptual Art: A Critical Anthology Alexander Alberro Blake Stimson, Editors The MIT Press conceptual art conceptual art: a critical anthology edited by alexander alberro and blake stimson the MIT press • cambridge, massachusetts • london, england ᭧1999 Massachusetts Institute of Technology All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form by any electronic or mechanical means (including photocopying, recording, or information storage and retrieval)without permission in writing from the publisher. This book was set in Adobe Garamond and Trade Gothic by Graphic Composition, Inc. and was printed and bound in the United States of America. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Conceptual art : a critical anthology / edited by Alexander Alberro and Blake Stimson. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 0-262-01173-5 (hc : alk. paper) 1. Conceptual art. I. Alberro, Alexander. II. Stimson, Blake. N6494.C63C597 1999 700—dc21 98-52388 CIP contents ILLUSTRATIONS xii PREFACE xiv Alexander Alberro, Reconsidering Conceptual Art, 1966–1977 xvi Blake Stimson, The Promise of Conceptual Art xxxviii I 1966–1967 Eduardo Costa, Rau´ l Escari, Roberto Jacoby, A Media Art (Manifesto) 2 Christine Kozlov, Compositions for Audio Structures 6 He´lio Oiticica, Position and Program 8 Sol LeWitt, Paragraphs on Conceptual Art 12 Sigmund Bode, Excerpt from Placement as Language (1928) 18 Mel Bochner, The Serial Attitude 22 Daniel Buren, Olivier Mosset, Michel Parmentier, Niele Toroni, Statement 28 Michel Claura, Buren, Mosset, Toroni or Anybody 30 Michael Baldwin, Remarks on Air-Conditioning: An Extravaganza of Blandness 32 Adrian Piper, A Defense of the “Conceptual” Process in Art 36 He´lio Oiticica, General Scheme of the New Objectivity 40 II 1968 Lucy R. -

Interfaith Harmony in Pakistan: an Analysis Introduction

URL: http://dx.doi.org/10.31703/gpr.2020(V-I).02 DOI: 10.31703/gpr.2020(V-I).02 Citation: Akbar, M., & Yaseen, H. (2020). Interfaith Harmony in Pakistan: An Analysis. Global Political Review, V(I), 9-18 DOI:10.31703/gpr.2020(V-I).02 Vol. V, No. I (Winter 2020) Pages: 9 – 18 Interfaith Harmony in Pakistan: An Analysis Muqarrab Akbar* Hafsa Yaseen† p- ISSN: 2520-0348 e- ISSN: 2707-4587 Abstract Pakistan is a religious and Islamic state. The religion p- ISSN: 2520-0348 followed in Pakistan is Islam with a proportion of 98% being a peaceful religion; it protects the rights of every individual without discrimination of any religion. The constitution of Pakistan also protects Headings the rights of every citizen. In this paper, the researchers have tried to • Abstract figure out the meaning of interfaith harmony and how state policies and • Key Words state politicians are playing their role in promoting peace and harmony. • Introduction Quantitative research method is followed by filling the questionnaires by • Literature Review the respondents mostly from the South Punjab region. The sample • Religion in Pakistan population was Muslims and Non-Muslims. In the end, researchers • Interfaith Harmony in Pakistan evaluated whether interfaith harmony prevails in Pakistan and non- • Research Methodology Muslims and whether they can enjoy the same rights as the Muslim • Conclusions citizens of Pakistan. • References Key Words: Pakistan, Religion, Harmony, Extremism, Violence, South Punjab Introduction Interfaith harmony means bringing peace and tranquility promoting among people by positivity. There is an interrelationship among people of different religious beliefs at the individual and institutional level which projects a positive picture in the polity of nations.