Rendlesham Coins for Ipswich Museum?

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Village Voice Issue June July 2021

VILLAGE VOICE Fornham All Saints Village Magazine Bumble Bee Bench on The Green June 2021 - July 2021 Issue No. 230 Fornham All Saints Parish Council Paul Purnell (Chairman) 01284 763701 Enid Gathercole (Vice Chair) 01284 767688 Cathy Emerson 01284 700550 Hugo Greer - Walker 07309 045130 Don Lynch 07557277067 Jill Mayhew 01284 723588 Mat Stewart 01284 701099 Chris�ne Mason (Parish Clerk) 07545 783987 Other Representa'ves Rebecca Hopfensperger 07876 683516 (District and County Councillor) Sarah Broughton 07929 305787 (District Councillor) Jo Churchill (Member of Parliament) 01284 752311 Bury St Edmunds Police Sta�on (Office) 01284 774105 Mee'ngs The Parish Council meets at 6:30 pm, on the third Tuesday of the following months: January, March, May, July, September and November. Website h5p://fornhamallsaints.suffolk.cloud Village Voice Online h5ps://fornhamallsaints.suffolk.cloud/our-village/village-newsle5er/ The ‘Village Voice’ is published by Fornham All Saints Parish Council. Views and opinions expressed in this magazine are not necessarily accepted as being those of Fornham All Saints Parish Council. The ‘Village Voice’ accepts all ar�cles, no�ces and adver�sements in good faith. We cannot be responsible for the content of any submissions, nor liable for the quality of goods or services adver�sed. Deadline for ar�cles to be included in the Aug / Sept 2021 issue is Mon 26 July 2021 2 TUT HILL CONSULTATION A MEETING WILL BE HELD IN THE COMMUNITY CENTRE A1101 BURY ROAD TUESDAY 22 JUNE 2021 at 7.00 pm TO DISCUSS THE PROPOSALS FOR THE FUTURE OF TUT HILL REPRESENTATIVES FROM WEST SUFFOLK COUNCIL & SUFFOLK HIGHWAYS WILL BE ON HAND TO ANSWER QUESTIONS --------------------------------------------------- THE PROPOSALS WILL THEN BE PUT TO A VOTE TO BE HELD IN THE VILLAGE HALL THE GREEN SATURDAY 26 JUNE 2021 BETWEEN 9.00 am and 2.00 pm 3 The Annual General Mee'ng of Fornham All Saints Parish Council was held virtually on 5 May 2021 at 6.30pm. -

Thursday, Dec. 1950

Second Day's Sale: THURSDAY, DEC. 1950 at 1 p.m. precisely LOT COMMONWEALTH (1649.60). 243 N Unite 1649, usual type with m.m. sun. Weakly struck in parts, otherwise extremely fine and a rare date. 244 A{ Crown 1652, usual type. The obverse extremely fine, the rev. nearly so. 245 IR -- Another, 1656 over 4. Nearly extremely fine. 246 iR -- Another, 1656, in good slate, and Halfcrown same date, Shilling similar, Sixpence 1652, Twopence and Penny. JtI ostly fine. 6 CROMWELL. 247* N Broad 1656, usual type. Brilliant, practically mint state, very rare. 1 248 iR Crown, 1658, usual type, with flaw visible below neck. Extremely fine and rare. 249 A{ Halfcrown 1658, similar. Extremely fine. CHARLES II (1660-85). 250* N Hammered Unite, 2nd issue, obu. without inner circle, with mark of value, extremely fine and rare,' and IR Hammer- ed Sixpence, 3rd issue, Threepence and Penny similar, some fine. 4 LOT '::;1 N Guinea 1676, rounded truncation. Very fine. ~'i2 JR Crowns 1662, rose, edge undated, very fine; and no rose, edge undated, fine. 3 _'i3 .-R -- Others, 1663, fine; and 1664, nearly very fine. 2 :?5-1 iR. -- Another, 1666 with elephant beneath bust. Very fine tor this rare variety. 1 JR -- Others, 1671 and 1676. Both better than fine. 2 ~56 JR -- Others of 1679, with small and large busts. Both very fine. 2 _57 /R -- Electrotype copy of the extremely rare Petition Crown by Simon. JR Scottish Crown or Dollar, 1682, 2nd Coinage, F below bust on obverse. A very rare date and in unttsually fine con- dition. -

Part of the Tide Collection Aldeburgh Times Woodbridge Talk Southwold Organ Saxmundham News Leiston Observer Halesworth Hoot Aldeburgh Times

...YOUR FREE LOCAL NEWS JULY 2021 ALDEBURGH TIMES PART OF THE TIDE COLLECTION ALDEBURGH TIMES WOODBRIDGE TALK SOUTHWOLD ORGAN SAXMUNDHAM NEWS LEISTON OBSERVER HALESWORTH HOOT ALDEBURGH TIMES Registered Charity No. 1105001 VIEW OUR FULL COLLECTION AT TIDECOLLECTION.COM FROM OUR EDITOR INSIDE YOUR Welcome to my first Aldeburgh Times, which I will now be MAGAZINE... editing in-house along with our other titles. ALDEBURGH YACHT CLUB 4 SCHOOLS SAILING PROGRAMME Local school children experience I’d like to start by wishing Penny all the very best for her sailing and develop life skills retirement, we will all miss her visits to the office and her SUMMER FUN WITH 6 contribution to the Tide Collection. ALDEBURGH MUSEUM A Story-teller, Talks, Walks and Louise hands-on Activities – bring along Gissing Please keep me informed of any events and activities if you are your young ones a member of a club or association or are involved in fundraisers, I will be happy to include details within these pages. My email is lou@tidecollection. LEISTON AIR CADETS 9 Adventure training, sports, BTECs & com. I would love to hear from you DoE Awards and more - Recruiting now Our cover photo, by Fleur Hayles, is of school children enjoying Aldeburgh Yacht DESERT RAIDS WITH 15 THE SAS Club’s Sailing programme. What a great way to improve their life skills, confidence, The story of Tony Hough health and wellbeing. See page 4 for more information about the AYC Schools (a member of Aldeburgh Golf Club for many years) Sailing Trust’s work written by his son Gerald Hough -

Bus Services Operating Through Rushmere St Andrew

Bus Services operating through Rushmere St Andrew Route 4 Ipswich to Bixley Farm via Felixstowe Road & Broke Hall Operated by Ipswich Buses (Tel 0800 919390) Web: www.ipswichbuses.co.uk Buses run Mondays to Saturdays (except public holidays), in the daytime - approximately every half hour. Route: Ipswich Tower Ramparts - Ipswich Old Cattle Market Bus Station – Felixstowe Road – Broke Hall –Bixley Farm (via Foxhall Road, Broadlands Way, District Centre & Bixley Drive). Click here for timetable details. Timetable history:- 01/11/15 Route and timetable changes 11/04/16 Timetable changes 04/09/16 Minor timetable change 18/02/18 Timetable changes, route no longer serves Ipswich Railway station or Martlesham Heath Route 63 Ipswich to Framlingham via Woodbridge Road, Kesgrave, Martlesham, Woodbridge, Wickham Market & Hacheston Operated by First In Norfolk & Suffolk (Tel 01473 253800) Web: www.firstgroup.com/ukbus/suffolk_norfolk One school days journey each way. Route: Ipswich Old Cattle Market Bus Station – Woodbridge Road - Kesgrave (Main Road) – Fentons Way (4 services only) – Cambridge Road / Edmonton Close (3 services only) Martlesham Tesco - Woodbridge – Melton Chapel – Ufford – Wickham Market – Hacheston – Framlingham (Thomas Mills) All services are wheelchair and buggy-accessible. Click here for timetable details. Timetable history:- 30/08/15 Timetable changes 03/01/16 Timetable changes 27/03/16 Timetable changes 02/07/17 Extended route, now school days only – otherwise remainder within 64 service. Route 64 Ipswich to Aldeburgh via Woodbridge Road, Woodbridge, Melton, Saxmundham & Leiston Operated by First In Norfolk & Suffolk (Tel 01473 253800) Web: www.firstgroup.com/ukbus/suffolk_norfolk Buses run Mondays to Saturdays (except public holidays), in the daytime and early evening – typically every hour. -

Ancient, Islamic, British and World Coins Historical Medals and Banknotes

Ancient, Islamic, British and World Coins Historical Medals and Banknotes To be sold by auction at: Sotheby’s, in the Upper Grosvenor Gallery The Aeolian Hall, Bloomfield Place New Bond Street London W1 Day of Sale: Tuesday 9 June 2009 at 10.00 am and 2.00 pm Public viewing: 45 Maddox Street, London W1S 2PE Thursday 4 June 10.00 am to 4.30 pm Friday 5 June 10.00 am to 4.30 pm Monday 8 June 10.00 am to 4.30 pm Or by previous appointment. Catalogue no. 37 Price £10 Enquiries: James Morton, Tom Eden, Paul Wood, Jeremy Cheek or Stephen Lloyd Cover illustrations: Lots 1-57 (front); Lot 367 (back); Lot 335 (inside front cover); Lot 270 (inside back cover) in association with 45 Maddox Street, London W1S 2PE Tel.: +44 (0)20 7493 5344 Fax: +44 (0)20 7495 6325 Email: [email protected] Website: www.mortonandeden.com This auction is conducted by Morton & Eden Ltd. in accordance with our Conditions of Business printed at the back of this catalogue. All questions and comments relating to the operation of this sale or to its content should be addressed to Morton & Eden Ltd. and not to Sotheby’s. Important Information for Buyers All lots are offered subject to Morton & Eden Ltd.’s Conditions of Business and to reserves. Estimates are published as a guide only and are subject to review. The actual hammer price of a lot may well be higher or lower than the range of figures given and there are no fixed “starting prices”. -

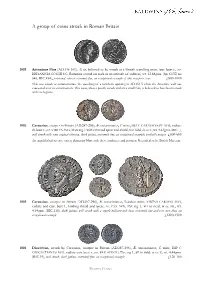

A Group of Coins Struck in Roman Britain

A group of coins struck in Roman Britain 1001 Antoninus Pius (AD.138-161), Æ as, believed to be struck at a British travelling mint, laur. bust r., rev. BRITANNIA COS III S C, Britannia seated on rock in an attitude of sadness, wt. 12.68gms. (Sp. COE no 646; RIC.934), patinated, almost extremely fine, an exceptional example of this very poor issue £800-1000 This was struck to commemorate the quashing of a northern uprising in AD.154-5 when the Antonine wall was evacuated after its construction. This issue, always poorly struck and on a small flan, is believed to have been struck with the legions. 1002 Carausius, usurper in Britain (AD.287-296), Æ antoninianus, C mint, IMP C CARAVSIVS PF AVG, radiate dr. bust r., rev. VIRTVS AVG, Mars stg. l. with reversed spear and shield, S in field,in ex. C, wt. 4.63gms. (RIC.-), well struck with some original silvering, dark patina, extremely fine, an exceptional example, probably unique £600-800 An unpublished reverse variety depicting Mars with these attributes and position. Recorded at the British Museum. 1003 Carausius, usurper in Britain (AD.287-296), Æ antoninianus, London mint, VIRTVS CARAVSI AVG, radiate and cuir. bust l., holding shield and spear, rev. PAX AVG, Pax stg. l., FO in field, in ex. ML, wt. 4.14gms. (RIC.116), dark patina, well struck with a superb military-style bust, extremely fine and very rare thus, an exceptional example £1200-1500 1004 Diocletian, struck by Carausius, usurper in Britain (AD.287-296), Æ antoninianus, C mint, IMP C DIOCLETIANVS AVG, radiate cuir. -

A REVIE\I\T of the COINAGE of CHARLE II

A REVIE\i\T OF THE COINAGE OF CHARLE II. By LIEUT.-COLONEL H. W. MORRIESON, F.s.A. PART I.--THE HAMMERED COINAGE . HARLES II ascended the throne on Maj 29th, I660, although his regnal years are reckoned from the death of • his father on January 30th, r648-9. On June 27th, r660, an' order was issued for the preparation of dies, puncheons, etc., for the making of gold and" silver coins, and on July 20th an indenture was entered into with Sir Ralph Freeman, Master of the Mint, which provided for the coinage of the same pieces and of the same value as those which had been coined in the time of his father. 1 The mint authorities were slow in getting to work, and on August roth an order was sent to the vVardens of the Mint directing the engraver, Thomas Simon, to prepare the dies. The King was in a hurry to get the money bearing his effigy issued, and reminders were sent to the Wardens on August r8th and September 2rst directing them to hasten the issue. This must have taken place before the end of the year, because the mint returns between July 20th and December 31st, r660,2 showed that 543 lbs. of silver, £r683 6s. in value, had been coined. These coins were considered by many to be amongst the finest of the English series. They fittingly represent the swan song of the Hammered Coinage, as the hammer was finally superseded by the mill and screw a short two years later. The denominations coined were the unite of twenty shillings, the double crown of ten shillings, and the crown of five shillings, in gold; and the half-crown, shilling, sixpence, half-groat, penny, 1 Ruding, II, p" 2. -

Quarterlymeetings

QUARTERLYMEETINGS. • ICRLINGITAM AND MILDENITALL, JUNE 5, 1851.—C. J. Fox Banbury, Esq., Prasident for the day. The companymet at the house of J. Gwilt, Esq., Icklingham,where that gentleman had arranged in one room a variety of Roman antiquities found at Icktingham,and in another a collectionof Saxon weaponsand ornaments,from the adjoiningparish of West Stow. • The paper by Sir Henry E. Bunbury, Bart., on the nature of the Roman occupationat Icklingham,whichis printed in p. 250,washere read. The Secretarythen gavea brief explanationofthe SaxonrelicsexhibitedbyMr. Gwilt,and calledattention to•the fact thatZrelics of the Anglo-Saxonperiod had beenfoundin Icklingham,whileon the Hedth in the adjoiningparish of Stow,and near to the site of the Roman camp at Icklingham,Saxon antiquities alone are found ; leading to the belief that the two races were here in opposition to each other. The number of skeletons found, and the nature of the objects discoveredwith them,lie observed,shew that Stow Heath must havebeen for a considerabletimeused as a burialplace. The relicsconsistof urns rudely designed, andformedbyhandout ofblackearth; bossesofshields,andspearsofiron,&c.; bronze fibulteand clasps,with fragmentsof cloth adheringto them; and beads. Thelatter are numerous,and principallyof amber; but some are of glass,of variouscolours, and others of bakedearth painted. Some of a black colour have the zig-zagorna- ment in white. A fewof polishedwhitepebblehavealsobeenmet with, and oneof jet. With a numberofvery smallamberbeadswerefoundsmallglasstriplet beads, and four Romansmallbrass coinspiercedas if to be worn with the beads. Among the bronzearticleswerea fewpiecesresemblingone figured in the last No. of the Institute's Proceedings; the use of whichis as yet unknown. Owingto the quantity of rain that had fallen,the party wereunableto proceed to the site of the Romancampor station; but went at onceto the churchof AllSaints, whereMr. -

Schedule of Current and Proposed Polling Districts and Polling Places 2018

Schedule of current and proposed Polling Districts and Polling Places 2018 Colour-coded cells represent polling districts that share use of a venue No. of voters allocated to Forecast No. of Revised Polling Current venue voters allocated Polling Revised Proposed Future Assigned District Polling District Name Polling Station Venue Parish Current Ward Constituency Revised Ward Parish Ward Comments on PD Comments / PSI Reports etc re Polling Station LA (1 Dec 2017) to venue District Constituency Polling Place Code * indicates split (2023) Code register 1 B SCDC Badingham Badingham Village Hall Badingham Hacheston Central Suffolk 406 434 SFRBA Framlingham n/a No change necessary. 2 BCX SCDC Great Bealings Bealings Village Hall Great Bealings Woodbridge Central Suffolk 219 228 SCFGB Suffolk Coastal Carlford & Fynn Valley n/a No change necessary. 2 BCY SCDC Little Bealings Bealings Village Hall Little Bealings Woodbridge Central Suffolk 379 372 SCFLB Suffolk Coastal Carlford & Fynn Valley n/a No change necessary. 3 BI SCDC Brandeston Brandeston Village Hall Brandeston Framlingham Central Suffolk 250 243 SFRBR Framlingham n/a No change necessary. 4 BJX SCDC Bredfield The Church Room, Bredfield Bredfield Grundisburgh Central Suffolk 283 283 SCFBR Carlford & Fynn Valley n/a No change necessary. 4 BJY SCDC Boulge The Church Room, Bredfield Boulge (PM) Grundisburgh Central Suffolk 20 22 SCFBO Carlford & Fynn Valley n/a No change necessary. 5 BL SCDC Bruisyard Bruisyard Village Hall Bruisyard Hacheston Central Suffolk 137 137 SFRBD Framlingham n/a No change necessary. 6 CA SCDC Charsfield Charsfield Village Hall Charsfield Wickham Market Central Suffolk 291 325 SCFCH Carlford & Fynn Valley n/a No change necessary. -

MAP BOOKLET Site Allocations and Area Specific Policies

MAP BOOKLET to accompany Issues and Options consultation on Site Allocations and Area Specific Policies Local Plan Document Consultation Period 15th December 2014 - 27th February 2015 Suffolk Coastal…where quality of life counts Woodbridge Housing Market Area Housing Market Settlement/Parish Area Woodbridge Alderton, Bawdsey, Blaxhall, Boulge, Boyton, Bredfield, Bromeswell, Burgh, Butley, Campsea Ashe, Capel St Andrew, Charsfield, Chillesford, Clopton, Cretingham, Dallinghoo, Debach, Eyke, Gedgrave, Great Bealings, Hacheston, Hasketon, Hollesley, Hoo, Iken, Letheringham, Melton, Melton Park, Monewden, Orford, Otley, Pettistree, Ramsholt, Rendlesham, Shottisham, Sudbourne, Sutton, Sutton Heath, Tunstall, Ufford, Wantisden, Wickham Market, Woodbridge Settlements & Parishes with no maps Settlement/Parish No change in settlement due to: Boulge Settlement in Countryside (as defined in Policy SP19 Settlement Hierarchy) Bromeswell No Physical Limits, no defined Area to be Protected from Development (AP28) Burgh Settlement in Countryside (as defined in Policy SP19 Settlement Hierarchy) Capel St Andrew Settlement in Countryside (as defined in Policy SP19 Settlement Hierarchy) Clopton No Physical Limits, no defined Area to be Protected from Development (AP28) Dallinghoo Settlement in Countryside (as defined in Policy SP19 Settlement Hierarchy) Debach Settlement in Countryside (as defined in Policy SP19 Settlement Hierarchy) Gedgrave Settlement in Countryside (as defined in Policy SP19 Settlement Hierarchy) Great Bealings Currently working on a Neighbourhood -

Hawks, Ospreys and Students Union Unite for Sport

EASTER 2009 Hawks, Ospreys and Students Union unite for Sport Tom Chigbo, President of CUSU 2009-10, writes:: 800 Years With No Sports Centre Reading recent editions of The Hawk evokes conflicting emotions. First, pride. It serves as a fine reminder of the excellent sporting tradition of Cambridge University. From the famous names who continue to compete at the highest level, to the thousands of students, coaches and volunteers who ensure that quality sport is played every day at University, College and recreational level in Cambridge. Nevertheless, as readers of this newsletter, you will be more than familiar with the urgent need for a University Sports Centre. Indeed, it is probably a source of great disappointment, as for years you have seen this noble ambition met with so many false starts. After all, land and planning permission (which has since been renewed) were acquired in West Cambridge back in 1999. Fully-costed designs and specifications along with a budget for the running costs (the sports centre can be self funding) already exist. Some of you may even recall the McCrum report of 1973, which originally highlighted the need for centralised University sports facilities. In fact, further research has shown that even our Victorian predecessors had identified this necessity, shown in an article in the Cambridge Review of 1892. However, time has not proved to be a great healer. The absolute necessity of a University sports centre has not Proposed Sports Centre, Perspective sketches diminished over the years. Instead, it continues to grow. It grows each year with the rising cost of pool hire, now so great that the Swimming and Water Polo Club cannot afford a coach. -

Babergh District Council Work Completed Since April

WORK COMPLETED SINCE APRIL 2015 BABERGH DISTRICT COUNCIL Exchange Area Locality Served Total Postcodes Fibre Origin Suffolk Electoral SCC Councillor MP Premises Served Division Bildeston Chelsworth Rd Area, Bildeston 336 IP7 7 Ipswich Cosford Jenny Antill James Cartlidge Boxford Serving "Exchange Only Lines" 185 CO10 5 Sudbury Stour Valley James Finch James Cartlidge Bures Church Area, Bures 349 CO8 5 Sudbury Stour Valley James Finch James Cartlidge Clare Stoke Road Area 202 CO10 8 Haverhill Clare Mary Evans James Cartlidge Glemsford Cavendish 300 CO10 8 Sudbury Clare Mary Evans James Cartlidge Hadleigh Serving "Exchange Only Lines" 255 IP7 5 Ipswich Hadleigh Brian Riley James Cartlidge Hadleigh Brett Mill Area, Hadleigh 195 IP7 5 Ipswich Samford Gordon Jones James Cartlidge Hartest Lawshall 291 IP29 4 Bury St Edmunds Melford Richard Kemp James Cartlidge Hartest Hartest 148 IP29 4 Bury St Edmunds Melford Richard Kemp James Cartlidge Hintlesham Serving "Exchange Only Lines" 136 IP8 3 Ipswich Belstead Brook David Busby James Cartlidge Nayland High Road Area, Nayland 228 CO6 4 Colchester Stour Valley James Finch James Cartlidge Nayland Maple Way Area, Nayland 151 CO6 4 Colchester Stour Valley James Finch James Cartlidge Nayland Church St Area, Nayland Road 408 CO6 4 Colchester Stour Valley James Finch James Cartlidge Nayland Bear St Area, Nayland 201 CO6 4 Colchester Stour Valley James Finch James Cartlidge Nayland Serving "Exchange Only Lines" 271 CO6 4 Colchester Stour Valley James Finch James Cartlidge Shotley Shotley Gate 201 IP9 1 Ipswich