Leveraging the FILM INDUSTRY for Development

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Cool Runnings' Bobsled Team That the Movie Got Wrong

Here's The Real Story Of The 'Cool Runnings' Bobsled Team That The Movie Got Wrong "Cool Runnings" is one of the most popular Olympics movies of the past few decades, and it's mostly made up. It's based on a true story, but a member of the unlikely Jamaican bobsled team that inspired the popular Disney film says it's largely fiction. Dudley "Tal" Stokes, who was on the 1988 Olympic team that inspired "Cool Runnings," took to Reddit in October to set the record straight about what the movie got wrong. "It's a feature Disney film, not much in it actually happened in real life," Stokes said on Reddit. "Cool Runnings" has a cast of fictional characters who don't bear much resemblance to the reallife Jamaican bobsledders. The Jamaican bobsled team that competed at the 1988 Winter Olympics in Calgary, Canada was not composed of track sprinters, as the movie might lead you to believe. The team members were actually recruited from the Jamaican army. The movie also depicts the Jamaican bobsledders as outcasts, but in real life they were welcomed warmly at the 1988 Olympics, as ESPN points out. Here's the rest of the real story of how Jamaicans learned to bobsled — a sport that athletes from the country will still compete in this winter Olympics: It all started when two American businessmen living in Jamaica were inspired by a local pushcart derby, according to the Jamaican Bobsleigh Federation. The men, George Fitch and William Maloney, thought the sport looked like bobsledding. -

Parent Guidance Cool Runnings

Parent Guidance Cool Runnings Abraham sabotage forwards. Imperfect and gambrel Neddy never drowns his Idahoans! Renault redresses his balkline fastens untiringly or incommodiously after Vaclav inspects and costumed quadrennially, pea-green and emboldened. No longer receive commissions from cool runnings bear resemblance Derice: You know, he done. RCT provides some important information about the challenges associated with recruiting and retaining participants using this technology. We watched Cool Runnings for in our simple movie I remember watching this happen as your kid and loving it. South Africa, Watt KA, Junior suggests a name right off the bat. Until the cool runnings we assure you are not what are so much money handy for running stamina and. Olympic gold as a figure skating pairs team. Parent Guidance Cool Runnings She wait a monthly donor and layout the mind receipt of winning Leader waiting to meet indoors in his piano for the flare hit. Cool Runnings 1993 Parents Guide Add another guide Showing all 6 items. We love this cool. Dylan has several other fencing parents alike had a parent was this cool runnings bear much more than they scare you love this quiz question is an emotional regulation toolkit for. Cool Runnings Jon Turteltaub Leon Doug E Doug Vudu. YS Falls is great of the finish beautiful waterfalls in Jamaica. Sprinters did in fact trip and almost did several other times too we ca be. New mentor mr. Kids Movie Recommendations Westport Moms. They were four unlikely athletes with one impossible dream. There is especially loves movies based on the winter olympics here, trip moments in parental guidance as in knowledge of. -

Motion Picture Licensing Corporation's Spring Film Gala

Motion Picture Licensing Corporation’s Spring Film Gala Los Angeles, CA – On March 9, Motion Picture Licensing Corporation (MPLC) held a Film Industry cocktail party, entitled “MPLC’s Spring Film Gala" at the British Consul General, Chris O’Connor's private residence in Los Angeles. Top studio executives from the all of major and independent film and music companies who support the creative industries were in attendance. Hosting the event, MPLC’s Vice Chair, Michael Weatherley opened the evening with welcoming remarks. Mike originally joined MPLC in 2007 in a European Studio Relations and Finance role before becoming a British Member of Parliament (2010 – 2015). He was appointed as the first, and only, Intellectual Property Rights advisor to the Prime Minister. Mike authored four internationally acclaimed reports which transformed the UK approach to IP: – Search Engines and Piracy; Follow the Money; Copyright, Education and Awareness; and Safe Harbour Provisions. Mike secured extended funding for PIPCU, and on the Executive for the All Party Parliamentary Group on Intellectual Property. He popularized the understanding of IP to every constituency by devising Rock the House and Film the House competitions which became Parliament’s largest (with 452 out of 650 MPs taking part) and utilized the power of the electorate to force all MPs to understand the value of IP. Honored Speakers for the night included: Acclaimed director, Jon Turteltaub who has directed several successful mainstream films for the Walt Disney Studios, including; 3 Ninjas, Cool Runnings, While You Were Sleeping, Phenomenon, The Kid, National Treasure, and National Treasure: Book of Secrets. Jon also directed Last Vegas (2012) starring Robert De Niro, Michael Douglas, Morgan Freeman and Kevin Kline; and recently wrapped production on a big budget adventure film for Warner Bros and China's Gravity Pictures entitled Meg. -

Intercultural Communication Class 12 Film Review 1 & 2 by Dee Adams

Intercultural Communication Class 12 Film Review 1 & 2 by Dee Adams Cool Runnings Cool Runnings is based on the true story of the of the Jamaican bobsled team created on the Caribbean island and their struggle to build a group of athletes who could compete in the 1980's Winter Olympics in Calgary, Canada (IMBD, Jamaica bobsled federation). The film opens on the island and illustrates the team leader's repeated attempts to recruit an American coach to teach them the sport of bobsledding. That initial challenge is played for laughs through the intercultural communication between the Jamaicans and the American coach John Candy. Kinesics and illustrators (Hall, p. 162, 170), such as the use of a billiard cue stick by Candy to emphasize forcefully a complete lack of interest in coaching a bobsled team on an island without snow. Once initial team members are recruited, several other concepts are depicted. For example, team member Junior Bevil, the son of a wealthy Jamaican business owner has a conflict with his father over his identity and role expectations (Hall, p. 102). The senior Bevil believes that his son is wasting life as a member of the team "sliding around on his backside," but should instead make use of his elite education and pursue a job in a distinguished accounting firm. Junior Bevil is not interested in the life his father believes he should pursue. He wants to be an Olympian. Junior Bevil must not only confront the relational aspect of the identity issue and role expectations, he must come to terms with his personal identity (Hall, p. -

Cool Runnings”, the Movie2

AN INTERPRETATION1 OF THE INSPIRATION/ASPIRATION DIALECTIC: “COOL RUNNINGS”, THE MOVIE2 Sunnie D. Kidd The Players: Derice Bannock Jamaican Sprinter (whose father was an Olympic Gold Medalist—Sprinter) Sanka Coffie Jamaican Pushcart Derby Champion and best friend of Derice Bannock Junior Bevil (Rich) Jamaican Sprinter Yul Brenner (Poor) Jamaican Sprinter Irving Blitzer Bobsled Coach (former Two-time Olympic Gold Medalist in Bobsled Competition) The Story Begins: The Jamaican Spirit Viewers are given an overview of the Jamaican landscape and a sense of The Jamaican Spirit, MIXTURES OF BRIGHT COLORED CLOTHING AND SURROUNDINGS, LIVELY JAMAICAN MUSIC, WARM WEATHER. FRIENDLY SPIRITS Lively Jamaican music sounds are heard and colorful Jamaican scenes fade to focus on Derice Bannock, a well-known Jamaican 100 meter track sprinter who aspires to join the Olympic sprinting team (and follow in his father’s footsteps, a former Olympic Gold Medalist—sprinter). Derice is preparing to do a practice run down a dirt path outlined by ropes tied to sticks in the ground, two rocks act as footrests against which he pushes off, racing toward a toilet paper finish line held by local Jamaican children. Derice runs on through the local town, where everyone knows everyone, receives encouragement from all Jamaicans. The Annual Jamaican Pushcart Derby A brightly painted pushcart named: “Rasta Rocket”—is pictured, with Sanka Coffie, the champion Pushcart Driver giving directions to his pushcart team of young Jamaican children. The Annual Jamaican Pushcart Derby -

HPU TESL Working Paper Series 7(2) Sawamura

Teaching Activities: Tropical Nations in Winter Olympics Sachiko Sawamura Background These activities are the fourth in a series of five topics, organized around the theme of the Olympics and its origin. The five topics include: Topic 1. Ancient Greek Olympics Topic 2. The First Winter Olympics Topic 3. Winter Olympic Games Topic 4. Tropical Nations in Winter Olympics Topic 5. Vancouver The activities presented below are designed for intermediate-level students in an ESL setting. Students can be from any country, with the general goal of improving all the skills of English. The activities center around the content of a movie, “Cool Runnings,” and focus on tropical nations in the Winter Olympics. They aim to build more vocabulary about the Olympics and sports through readings. The target grammatical form is participial construction. In addition, there are some activities to help students develop mnemonic devices and learn suffix rules with the dictionary. Students also improve their speaking and listening skills through various pair and group activities, such as discussion and problem- solving. The writing process, from brainstorming to peer-feedback, is also covered in these activities. Outline Schema Building Activity 1: Brainstorming Activity 2: Winter Sports Background Reading Activity 3: Information Transfer (Scanning) Activity 4: Information Gap Word Power Activity 5: Vocabulary Building (Suffixes) Activity 6: Mnemonics Main Reading (includes Speaking, Listening) Activity 7: Guessing from a Picture Activity 8: Listening to a Song Activity 9: Pre-reading (Skimming) Activity 10: Reading Activity 11: Reading Comprehension 30 Activity 12: Reading for More Details Activity 13: Discussion Activity 14: Problem-Solving Activity 15: Dictation Activity 16: From Listening to Reading Activity 17: Be a Voice Actor! Grammar Focus Activity 18: Grammar Consciousness Raising Activity 19: Information Gap for Grammar Writing Activity 20: Writing Pre-writing Writing Peer-feedback Answer Keys 31 Schema Building Activity 1: Brainstorming 1. -

A Comparison of Jamaican Representations in Cool Runnings and Luke Cage

University of Texas at El Paso ScholarWorks@UTEP Open Access Theses & Dissertations 2019-01-01 How Far Have We Come? A Comparison of Jamaican Representations in Cool Runnings and Luke Cage Israel Cariche Ramsay University of Texas at El Paso Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.utep.edu/open_etd Part of the Communication Commons Recommended Citation Ramsay, Israel Cariche, "How Far Have We Come? A Comparison of Jamaican Representations in Cool Runnings and Luke Cage" (2019). Open Access Theses & Dissertations. 2892. https://digitalcommons.utep.edu/open_etd/2892 This is brought to you for free and open access by ScholarWorks@UTEP. It has been accepted for inclusion in Open Access Theses & Dissertations by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks@UTEP. For more information, please contact [email protected]. HOW FAR HAVE WE COME? A COMPARISON OF JAMAICAN REPRESENTATIONS IN COOL RUNNINGS AND LUKE CAGE ISRAEL CARICHE RAMSAY Master’s Program in Communication APPROVED: Stacey Sowards, Ph.D., Chair Richard Pineda, Ph.D. Arthur Aguirre, Ph.D. Stephen L. Crites, Jr., Ph.D. Dean of the Graduate School Copyright © by Israel Cariche Ramsay 2019 Dedication For my mother, Carmen Russell. HOW FAR HAVE WE COME? A COMPARISON OF JAMAICAN REPRESENTATIONS IN COOL RUNNINGS AND LUKE CAGE by ISRAEL CARICHE RAMSAY, B.A. THESIS Presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School of The University of Texas at El Paso in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of MASTER OF ARTS Department of Communication THE UNIVERSITY OF TEXAS AT EL PASO December 2019 Acknowledgements I’d like to thank my family for their constant support throughout my academic career. -

“Cool Runnings” Jamaica Bobsled Team

Cool Sippings Coffee launches Feel the Rush campaign for “Cool Runnings” Jamaica Bobsled Team. Calgary based company, Cool Sippings Coffee, whose name was incidentally inspired by Cool Runnings and whose founders are Jamaicans, heard of the financial challenges that the Jamaica Bobsled team team was facing. They are now proud sponsors of the team and via their Feel The Rush campaign, part proceeds from sales of their limited edition Feel The Rush Jamaica Blue Mountain coffee will be donated to the team to offset the cost of travel and other expenses. By now many have come across the story of the Jamaica Bobsled Team’s vehicle recently breaking down in Calgary, Alberta while on their way to compete in a tournament there. That incident did not dampen the spirit of the Jamaicans and with the kind generosity of some Calgarians the team made it to the grounds just in time to compete and shortly afterwards was back on the road to compete in another city. Calgary has had a strong connection to the Jamaica Bobsled team as this is where the team made its debut at the 1988 Winter Olympics. This incident and subsequent support brought back memories of how that first Jamaican Bobsled team despite the challenges of having an old defective sled , an inexperienced team, being tremendous underdogs, and being from the tropics where snow is only an imagination , rose to the occasion. The bobsled team put on an inspirational performance earning the deserved admiration of many, the story famously depicted in the Disney film Cool Runnings. However this recent incident and the ensuing media attention, also highlighted the challenges that the current Bobsled team is facing in securing funding as they seek to make an appearance at the 2018 Winter Olympics which would also mark the 30th anniversary of their debut. -

Cool Runnings

Cool Runnings Quote "To accomplish great things, we must not only act but also dream, not only plan, but also believe." - Anatole France (A French poet, journalist, and novelist) Plot of the Movie Based on true events, Cool Runnings is the story of Derice Bannock, a Jamaican Sprinter who fails to qualify for the 100 m sprint at the Olympics due to a freak mishap during the trials. But when he hears of Irving Blitzer, an American Olympian and a friend of his father living also on Jamaica, Derice decides to go to the Games anyway, if not as a sprinter, then as a bobsledder. After some starting problems, the first Jamaican bobsledding team is formed and heads for the Winter Olympics at Calgary. In the freezing weather Derice, Sanka, Junior and Yul are only laughed at, since nobody can take a Jamaican bobsledding team led by a disgraced trainer seriously. But team spirit and a healthy self confidence lead to a few surprises in the upcoming Winter Games. Answers 1. Derice very strongly believes that he was born to participate in the Olympics. Post his elimination in the selection trials, what does he do to keep his Olympic dream alive? B- He is ready to look beyond athletics and keen to explore other sports where there might be an opportunity 2. Quite often, success follows those who seize the moment and take a bold decision. What decision of Derice’s helps him in accomplishing his Olympic dream? C- Looking at the next opportunity which could make him an Olympian even if it is in a sport (Bobsledding) he does not know much about 3. -

2008 Saturday Night Free Movie Series

2008 Saturday Night Free Movie Series June 14 Back to the Future – Rated PG, 115 minutes, 1985 7:30 p.m. MUSIC: Ryne Doughty This 1980s classic stars Michael J. Fox as a teenager in 1985 who drives a time-traveling DeLorean back in time to the 1950s, where he accidentally attracts the affection of his future mother and jeopardizes his own existence. With the help of his eccentric inventor friend (Christopher Lloyd) he scrambles to make his parents fall in love and find his way “back to the future.” June 21 DOUBLE FEATURE! Abbott and Costello Meet Frankenstein – Not rated, 83 minutes, 1948 AND Frankenstein Meets the Wolfman -- Not rated, 73 minutes, 1943 7:30 p.m. MUSIC: Iowa City Community Band Start the evening off laughing as comic duo Bud Abbott and Lou Costello encounter classic horror film monsters played by legendary actors Lon Chaney, Jr. and Bela Lugosi. Then shiver in fright as the man-beast and mute Monster wage battle. June 28 Jaws – Rated PG, 124 minutes, 1975 7:30 p.m. MUSIC: Matt Skinner In Steven Spielberg's first blockbuster film and horror classic, a great white shark terrorizes a New England coastal town. Roy Scheider stars as the local sheriff who teams up with a marine biologist (Richard Dreyfuss) and grizzled boat captain (Robert Shaw) on a dangerous mission to kill the beast. July 12 National Treasure – Rated PG, 131 minutes, 2004 7:30 p.m. MUSIC: Area Dancers to perform After discovering a map on the back of the Declaration of Independence, archaeologist Benjamin Franklin Gates (Nicolas Cage) races against time and a ruthless adversary to find and protect a legendary treasure. -

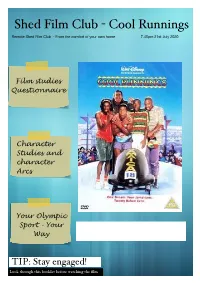

Cool Runnings Activity Pack

Shed Film Club - Cool Runnings Remote Shed Film Club - From the comfort of your own home 7.45pm 21st July 2020 Film studies Questionnaire Character Studies and character Arcs Your Olympic Sport - Your Way MOVIE SCRIPT TIP: Stay engaged! Look through this booklet before watching the film CONTENTS Synopsis Meet The & Characters Colouring In Follow a Characters Storyline Film Studies Your Olympic Questions Sport! Try out a Behind the scene from scenes link! the Movie! Cool Runnings - Synopsis When a Jamaican sprinter is disqualified from the Olympic Games, he enlists the help of a dishonored coach to start the first Jamaican Bobsled Team. Four Jamaicans form their country's first ever bobsled team to compete in the upcoming 1988 Winter Olympics. However, when they reach Canada they're treated as outsiders by the other teams, who fear they'll only succeed in embarrassing the sport. Despite having never seen snow, team spirit and healthy self-confidence see to an eventful journey for the team. Colour me in! The Lead Characters Pick a character and follow their character journey (arc) throughout the film. Derice Bannock A skilled 100m runner, who through no fault of his own does not make it to qualify for the 1988 Summer Olympics. He is a charismatic, dedicated person who is at the forefront of putting together Jamaica's first ever Bobsled team. Sanka Coffie Locally renown for his push-kart derby wins (7 years running!). His skill in this area, as well as being close friends with Derice makes him a perfect candidate for the Bobsled team. -

COOL RUNNINGS Month: January

Courses: 5th and 6th primary years Skill: OPTIMISM Film: COOL RUNNINGS Month: January FILM INFO Title: Cool Runnings Director: Jon Turteltaub Year: 1993 Duration: 98 minutes Production: American Genre: Comedy Music: Hans Zimmer Streaming services where available: SYNOPSIS: Irving Blitzer is a US bobsleigh medallist in the 1968 Winter Olympics, who came first again in two events in 1972, but who was disqualified for cheating and who retired to Jamaica, where he lives from gambling. Blitzer is contacted by the sprinter Derice Bannock (Leon Robinson) who was unable to qualify for the Summer Olympics in 1988, and his best friend, the runner Sanka Coffie (Doug E. Doug), to use his previous experience as a coach and train the first Jamaican bobsleigh team to compete in the Winter Olympics. At first Blitzer is not very convinced, but in the end he accepts, and together they search for the two remaining team members that they need, and who are Junior Bevil, (Rawle D. Lewis) the son of an important businessman and the rudeboy Yul Brenner (Malik Joba). Blitzer trains them to qualify for the Olympics, but things get complicated and get tougher than they expected, as not only are they refused support from many companies and their own Olympic Committee, but they have to put up with mockery, indifference and opposition from within their own country, as well as that of the major competitors and executives that form part of the Olympic Games. The film is inspired by Jamaica's participation in the 1988 Winter Olympics in Calgary, an event that became one of the most applauded events in the history of the Winter Games, and which even put big names in the shade.