Banking Regulation in the US and Basel III

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

("DSCC") Files This Complaint Seeking an Immediate Investigation by the 7

COMPLAINT BEFORE THE FEDERAL ELECTION CBHMISSIOAl INTRODUCTXON - 1 The Democratic Senatorial Campaign Committee ("DSCC") 7-_. J _j. c files this complaint seeking an immediate investigation by the 7 c; a > Federal Election Commission into the illegal spending A* practices of the National Republican Senatorial Campaign Committee (WRSCIt). As the public record shows, and an investigation will confirm, the NRSC and a series of ostensibly nonprofit, nonpartisan groups have undertaken a significant and sustained effort to funnel "soft money101 into federal elections in violation of the Federal Election Campaign Act of 1971, as amended or "the Act"), 2 U.S.C. 5s 431 et seq., and the Federal Election Commission (peFECt)Regulations, 11 C.F.R. 85 100.1 & sea. 'The term "aoft money" as ueed in this Complaint means funds,that would not be lawful for use in connection with any federal election (e.g., corporate or labor organization treasury funds, contributions in excess of the relevant contribution limit for federal elections). THE FACTS IN TBIS CABE On November 24, 1992, the state of Georgia held a unique runoff election for the office of United States Senator. Georgia law provided for a runoff if no candidate in the regularly scheduled November 3 general election received in excess of 50 percent of the vote. The 1992 runoff in Georg a was a hotly contested race between the Democratic incumbent Wyche Fowler, and his Republican opponent, Paul Coverdell. The Republicans presented this election as a %ust-win81 election. Exhibit 1. The Republicans were so intent on victory that Senator Dole announced he was willing to give up his seat on the Senate Agriculture Committee for Coverdell, if necessary. -

Going Nuts in the Nutmeg State?

Going Nuts in the Nutmeg State? A Thesis Presented to The Division of History and Social Sciences Reed College In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Bachelor of Arts Daniel Krantz Toffey May 2007 Approved for the Division (Political Science) Paul Gronke Acknowledgements Acknowledgements make me a bit uneasy, considering that nothing is done in isolation, and that there are no doubt dozens—perhaps hundreds—of people responsible for instilling within me the capability and fortitude to complete this thesis. Nonetheless, there are a few people that stand out as having a direct and substantial impact, and those few deserve to be acknowledged. First and foremost, I thank my parents for giving me the incredible opportunity to attend Reed, even in the face of staggering tuition, and an uncertain future—your generosity knows no bounds (I think this thesis comes out to about $1,000 a page.) I’d also like to thank my academic and thesis advisor, Paul Gronke, for orienting me towards new horizons of academic inquiry, and for the occasional swift kick in the pants when I needed it. In addition, my first reader, Tamara Metz was responsible for pulling my head out of the data, and helping me to consider the “big picture” of what I was attempting to accomplish. I also owe a debt of gratitude to the Charles McKinley Fund for providing access to the Cooperative Congressional Elections Study, which added considerable depth to my analyses, and to the Fautz-Ducey Public Policy fellowship, which made possible the opportunity that inspired this work. -

Chris Dodd for President

Speech to the 2007 DNC Winter Meeting | Chris Dodd for President http://chrisdodd.com/2007_DNC_Speech Chris Dodd for President Speech to the 2007 DNC Winter Meeting Thank you very, very much. What a great, great crowd. Good to see Democrats here in Washington. Give yourself a good round of applause. Let me begin by thanking those wonderful folks from Connecticut and elsewhere. I want to thank Nancy DiNardo, our state chair, and others who have come here today to be a part of this great effort. Howard, I want to thank you, as well, for your tremendous work. Mark, thank you for that very generous introduction. I always find, sometimes, the introductions go on longer than my remarks, from time to time in these matters. I was thinking, as Mark was going through the introduction, I come from a rather large family. I'm one of six children. And one of my older sisters introduced me -- or was present, rather, at an event where I was introduced a few months ago. And the master of ceremonies, not unlike Mark, went on at some length, and concluded the introduction by saying, "It now gives me a great deal of pleasure to present to you not only a great senator from Connecticut but one of the great leaders of the Western world." Well, you can imagine -- I'm there with my sister in the audience -- how much I appreciated those kind remarks. That evening, we're driving back to Providence, Rhode Island, where she lives. And during one of those quiet moments in the car, I turn to my sister, Martha, and I said, "Martha, how many great leaders of the Western world do you think there are?" Only as an older sister could do, she said, "One less than you think. -

Congressional Record United States Th of America PROCEEDINGS and DEBATES of the 115 CONGRESS, SECOND SESSION

E PL UR UM IB N U U S Congressional Record United States th of America PROCEEDINGS AND DEBATES OF THE 115 CONGRESS, SECOND SESSION Vol. 164 WASHINGTON, WEDNESDAY, APRIL 11, 2018 No. 58 House of Representatives The House met at 10 a.m. and was don’t think it is the investigation that wears a tan suit or salutes a marine called to order by the Speaker pro tem- is closing in on the President, but rath- while holding a cup of coffee, that is a pore (Mr. BACON). er his disgraceful reaction to it. constitutional crisis. But when the We now know, without any doubt, f President threatens to fire the special that the special counsel’s investigation counsel, well, you know. DESIGNATION OF SPEAKER PRO is closing in on the President and those We cannot rely on Republicans to de- TEMPORE very, very close to him. I don’t think fend democracy and our system of gov- The SPEAKER pro tempore laid be- lawful warrants legally executed ernment as long as they find political fore the House the following commu- against the homes, office, and hotel and personal advantage in walking nication from the Speaker: rooms of the President’s chief fixer and lockstep with the President, or they fellow grifter are the problem. tremble in fear of what would be in a WASHINGTON, DC, April 11, 2018. Rather, it is the constant threats to tweet if they stepped out of line. I hereby appoint the Honorable DON BACON further obstruct justice by a sitting And we as Democrats, well, we are in to act as Speaker pro tempore on this day. -

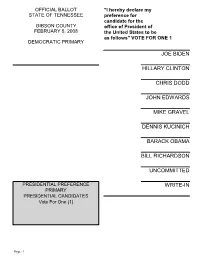

Joe Biden Hillary Clinton Chris Dodd John Edwards Mike Gravel Dennis Kucinich Barack Obama Bill Richardson Uncommitted Write-In

OFFICIAL BALLOT "I hereby declare my STATE OF TENNESSEE preference for candidate for the GIBSON COUNTY office of President of FEBRUARY 5, 2008 the United States to be as follows" VOTE FOR ONE 1 DEMOCRATIC PRIMARY JOE BIDEN HILLARY CLINTON CHRIS DODD JOHN EDWARDS MIKE GRAVEL DENNIS KUCINICH BARACK OBAMA BILL RICHARDSON UNCOMMITTED PRESIDENTIAL PREFERENCE WRITE-IN PRIMARY PRESIDENTIAL CANDIDATES Vote For One (1) Page: 1 PROPERTY ASSESSOR Vote For One (1) MARK CARLTON JOSEPH F. HAMMONDS JOHN MCCURDY GARY F. PASCHALL WRITE-IN Page: 2 OFFICIAL BALLOT "I hereby declare my STATE OF TENNESSEE preference for candidate for the GIBSON COUNTY office of President of FEBRUARY 5, 2008 the United States to be as follows" VOTE FOR ONE 1 REPUBLICAN PRIMARY RUDY GIULIANI MIKE HUCKABEE DUNCAN HUNTER ALAN KEYES JOHN MCCAIN RON PAUL MITT ROMNEY TOM TANCREDO FRED THOMPSON PRESIDENTIAL PREFERENCE UNCOMMITTED PRIMARY PRESIDENTIAL CANDIDATES Vote For One (1) WRITE-IN Page: 3 THE FOLLOWING OFFICE Edna Elaine Saltsman CONTINUES ON PAGES 2-5 John Bruce Saltsman, Sr. DELEGATES AT LARGE John "Chip" Saltsman, Jr. Committed and Uncommitted Vote For Twelve (12) Kari H. Smith MIKE HUCKABEE Michael L. Smith Emily G. Beaty Windy J. Smith Robert Arthur Bennett JOHN MCCAIN H.E. Bittle III Todd Gardenhire Beth G. Cox Justin D. Pitt Kenny D. Crenshaw Melissa B. Crenshaw Dan L. Hardin Cynthia H. Murphy Deana Persson Eric Ratcliff CONTINUED ON NEXT PAGE Page: 4 DELEGATES AT LARGE Matthew Rideout Committed and Uncommitted Vote For Twelve (12) Mahmood (Michael) Sabri RON PAUL Cheryl Scott William M. Coats Joanna C. -

Face the Nation."

© 2008, CBS Broadcasting Inc. All Rights Reserved. PLEASE CREDIT ANY QUOTES OR EXCERPTS FROM THIS CBS TELEVISION PROGRAM TO "CBS NEWS' FACE THE NATION." CBS News FACE THE NATION Sunday, March 2, 2008 GUESTS: Governor BILL RICHARDSON (D-NM) Senator CHRISTOPHER DODD (D-CT) Obama Surrogate Senator EVAN BAYH (D-IN) Clinton Surrogate MODERATOR/PANELIST: Mr. Bob Schieffer – CBS News This is a rush transcript provided for the information and convenience of the press. Accuracy is not guaranteed. In case of doubt, please check with FACE THE NATION - CBS NEWS (202)-457-4481 BOB SCHIEFFER, host: Today on FACE THE NATION, it's down to Texas and Ohio now. It'll be a showdown this Tuesday with contests there which could decide which Democrat will run against Senator John McCain, and the campaign rhetoric is red hot. Senator Hillary Clinton argues she's the one who's ready to be president. But is that fair to Senator Barack Obama? We'll talk to two senators on opposite sides: for Senator Obama, Chris Dodd, senator from Connecticut; for Senator Clinton, Evan Bayh, senator from Indiana. Then we'll talk to Governor Bill Richardson, who ran against both candidates, but who has not yet endorsed either. Will he make an endorsement? We'll find out. Then I'll have a final word on the passing of a conservative and a gentleman. But first, Texas and Ohio on FACE THE NATION. Announcer: FACE THE NATION, with CBS News chief Washington correspondent Bob Schieffer. And now, from CBS News in Washington, Bob Schieffer. SCHIEFFER: And good morning again. -

Generally Recognized Candidate List February 5, 2008 Presidential Primary

GENERALLY RECOGNIZED CANDIDATE LIST FEBRUARY 5, 2008 PRESIDENTIAL PRIMARY Joe Biden Democratic Biden for President, Inc. P.O. Box 438 Wilmington, DE 19899 Phone: (302) 574-2008 Website: http://www.joebiden.com/home Hillary Clinton Democratic Hillary Clinton for President 4420 North Fairfax Drive Arlington, VA 22203 Phone: (703) 469-2008 Website: http://www.hillaryclinton.com Chris Dodd Democratic Chris Dodd for President P.O. Box 51882 Washington, DC 20091 Phone: (202) 737-3633 Website: http://chrisdodd.com/home John Edwards Democratic John Edwards for President 410 Market Street, Suite 400 Chapel Hill, NC 27516 Phone: (919) 636-3131 Website: http://www.johnedwards.com Mike Gravel Democratic Mike Gravel for President P.O. Box 948 Arlington, VA 22216-0948 Phone: (703) 243-8303 Website: http://www.gravel2008.us Dennis Kucinich Democratic Kucinich for President 2008 11808 Lorain Avenue Cleveland, OH 44111 Phone: (877) 41-DENNIS Website: http://www.dennis4president.com/home Page 1 of 7 GENERALLY RECOGNIZED CANDIDATE LIST FEBRUARY 5, 2008 PRESIDENTIAL PRIMARY Barack Obama Democratic Obama for America P.O. Box 8102 Chicago, IL 60680 Phone: (866) 675-2008 Website: http://www.barackobama.com/ Bill Richardson Democratic National Headquarters - Albuquerque Office 111 Lomas Blvd. NW, Suite 200 Albuquerque, NM 87102 Phone: (505) 828-2455 Website: http://www.richardsonforpresident.com Sam Brownback Republican Brownback for President, Inc. Website: http://www.brownback.com John Cox Republican John Cox for President P.O. Box 5353 Buffalo Grove, IL 60089-5353 Phone: (877) 234-3800 Website: http://www.cox2008.com/cox Rudy Giuliani Republican Rudy Giuliani Presidential Committee, Inc. 295 Greenwich St, #371 New York, NY 10007 Phone: (212) 835-9449 Website: http://www.joinrudy2008.com Mike Huckabee Republican Huckabee for President, Inc. -

Former DNC Chairs Urge Fellow Democrats to Support Trade Promotion Authority

Former DNC Chairs Urge Fellow Democrats to Support Trade Promotion Authority March 26, 2015 To Fellow Members of the Democratic Party, As former DNC Chairs, we are proud to be leaders in a Party that seeks to strengthen the middle class and ensure America’s safety and security. To that end, we support granting Trade Promotion Authority (TPA) to President Obama. TPA originates from the earliest trade negotiating authority, passed by the New Deal Congress in 1934 and signed into law by President Franklin Delano Roosevelt. During the last four decades Congress has granted every President, Democrat and Republican alike, some version of trade promotion authority. To continue this bipartisan tradition, we stand behind the head of our Party, President Obama, in his quest for long-standing negotiating authority that allows Congress and the Executive branch to work together to pursue trade agreements that benefit Americans across the country. Moreover, TPA will clear a path for the President to pursue his pro-growth trade agenda—an agenda that will move America forward. As Democrats, we believe in rebuilding middle class security by putting Americans back to work. America's trade agreements are delivering for middle class families and our economic security. Our seventeen most recent trade agreements have improved the goods trade balance by $30 billion every year—that is some serious progress. The United States exported $2.35 trillion in Made-in-America goods and services in 2014, our fifth record-breaking year in a row. The increase in U.S. exports has contributed one-third of our economic growth and added $760 billion to our economy between 2009-2014. -

Articles with Major Mentions of Michael S. Barr January 20, 2009 – October 31, 2010

Articles with Major Mentions of Michael S. Barr January 20, 2009 – October 31, 2010 Cheyenne Hopkins, White House backs Itself into a Corner Letting CFPB Remain Leaderless, American Banker, August 27, 2010. WASHINGTON — Although President Obama made the creation of a Consumer Financial Protection Bureau a hallmark of the financial reform law enacted July 21, his delay in nominating the agency's first director could hamper its ability to get off the ground. With so much riding on the appointment, several observers had expected Obama to make his choice clear within days of the law's enactment. Instead, the absence of a pick has given rise to a grassroots campaign to appoint Elizabeth Warren to the job, which could create a political issue for the administration whether it ultimately chooses her or not. The Treasury Department, in the meantime, is tasked with getting the agency up and running, and observers said it is critical that a director be nominated and confirmed relatively soon. "There's a lot of operational work that can be done without a director being done, but some of the most profoundly difficult things comes down to having a leader," said Raj Date, the chairman and executive director of the Cambridge Winter Center for Financial Institutions Policy. "Leadership matters. If you are trying to have an agency that attracts the best and brightest for the sector, then you have to have a leader." Creating the consumer bureau was the first in a long list of tasks the agency must accomplish in its first year. Among other things, it must merge mortgage disclosure laws and outline a vision of its own authority. -

A Timeline of Republicans' Failure to Stop Reckless Mortgage Lending

A Timeline of Republicans’ Failure to Stop Reckless Mortgage Lending September 2010 Republican leaders in Congress are understandably eager to deflect attention away from their failure to rein in the reckless mortgage lending practices that contributed to the financial crisis. Republicans controlled the House, Senate*, and White House from January 2001 to January 2007, when subprime lending exploded and the housing bubble became fully inflated. That’s why, as a partisan diversionary tactic, Republicans have chosen to distort Chairman Frank’s record. As the timeline below shows, these Republican attacks are entirely baseless. The point here is not to litigate the past. The point is that, if Republicans have their way again, they will champion the same deregulatory and laissez faire economic policies that enabled Wall Street to take unacceptable risks and plunge the nation into economic crisis. In contrast, Democrats have passed legislation allowing the Treasury Department to place Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac into conservatorship and end the practices that put taxpayers at risk. Democrats have also passed far‐reaching Wall Street reform that includes protections against predatory lending; and they are working to ensure that Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac recover as much money as possible from unscrupulous lenders. At Wednesday’s hearing, Democrats will examine the GSEs’ progress in reforming their operations and limiting losses. 1994‐2000: Democratic legislation to give Fed authority to rein in predatory lending precedes Republican takeover of Congress and years of inaction 1994: In 1994, when Democrats controlled the House, Senate, and White House, they enacted the Homeownership and Equity Protection Act (HOEPA). -

The Iowa County December 2007

The Iowa County 1 December 2007 2 The Iowa County December 2007 ISAC OFFICERS Iowa County PRESIDENT December 2007 * Volume 36, Number 12 Kim Painter - Johnson County Recorder 1ST VICE PRESIDENT Mike King - Union County Supervisor The Iowa County: The official magazine of the 2ND VICE PRESIDENT Iowa State Association of Counties 501 SW 7th St., Ste. Q Des Moines, IA 50309 Gary Anderson - Appanoose County Sheriff (515) 244-7181 FAX (515) 244-6397 3RD VICE PRESIDENT www.iowacounties.org Chuck Rieken - Cass County Supervisor Rachel E. Bicego, EDITOR ISAC DIRECTORS Feature 4-10 Marjorie Pitts - Clay County Auditor Presdiential Candidate Articles Tim McGee - Lucas County Assessor Senator Joe Biden, Senator Chris Dodd, Paul Goldsmith- Lucas County Attorney Senator Hillary Clinton, Former Senator John Linn Adams - Hardin County Community Services Edwards, Senator John McCain, Senator Steve Lekwa - Story County Conservation Director Barack Obama, Governor Bill Richardson Derek White - Carroll County Emergency Mgmt. Robert Sperry - Story County Engineer Leadership Conference 2008 11 Brain Hanft - Cerro Gordo Co. Environ. Health Wayne Chizek - Marshall County GIS Capitol Comments 12 Timothy Hoschek - Des Moines County Supervisor Linda Hinton Wayne Walter - Winneshiek County Treasurer Les Beck - Linn County Zoning Legal Briefs 13 Denise Dolan - Dubuque County Auditor (Past Pres.) David Vestal Grant Veeder - Black Hawk County Auditor (NACo rep.) Case Management 14 ISAC STAFF Jackie Olson Leech William R. Peterson - Executive Director Lauren Adams - -

In Iowa Democratic Caucuses, Turnout Will Tell the Tale

ABC NEWS/WASHINGTON POST POLL: IOWA DEMOCRATIC CAUCUS EMBARGOED FOR RELEASE AFTER 12:01 a.m. Wednesday, Dec. 19, 2007 In Iowa Democratic Caucuses, Turnout Will Tell the Tale Turnout will tell the tale of the Iowa Democratic caucuses, where Barack Obama’s theme of a fresh start in the nation’s politics is resonating strongly against the bulwarks of Hillary Clinton’s campaign – strength, experience and electability. Likely caucus-goers are increasingly polarized between these two themes. Obama’s enlarged his already sizable lead among those looking mainly for new ideas and a new direction. But Clinton’s gained among those focused on strength and experience, and has eased some of her recent negatives on forthrightness and empathy. Clinton does better with voters who’ve definitely made up their minds, while Obama is stronger with changeable voters – still a third of the electorate. He may have more work to do to close the sale in the Iowa campaign’s final weeks. But Clinton has an equal challenge, motivating turnout; she’s weaker, and Obama is stronger, among those who say they’re absolutely certain to show up on caucus day. John Edwards, while trailing overall, also would benefit from low turnout by newcomers. Iowa Democratic Preference 50% Among likely Democratic caucus-goers ABC News/Washington Post polls 45% 40% Obama Clinton Edwards 35% 33% 30% 29% 25% 20% 20% 15% 10% 5% 0% July November Now Currently, among likely Democratic caucus-goers in this ABC News/Washington Post poll, 33 percent support Obama, 29 percent Clinton and 20 percent Edwards, with single- digit support for the other Democratic candidates.