Deconstructing Light

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Descriptive Psychopathology: the Signs and Symptoms of Behavioral

Descriptive Psychopathology Descriptive Psychopathology The Signs and Symptoms of Behavioral Disorders Michael Alan Taylor, MD Nutan Atre Vaidya, MD CAMBRIDGE UNIVERSITY PRESS Cambridge, New York, Melbourne, Madrid, Cape Town, Singapore, São Paulo Cambridge University Press The Edinburgh Building, Cambridge CB2 8RU, UK Published in the United States of America by Cambridge University Press, New York www.cambridge.org Information on this title: www.cambridge.org/9780521713917 © M. Taylor and N. Vaidya 2009 This publication is in copyright. Subject to statutory exception and to the provision of relevant collective licensing agreements, no reproduction of any part may take place without the written permission of Cambridge University Press. First published in print format 2008 ISBN-13 978-0-511-45779-1 eBook (NetLibrary) ISBN-13 978-0-521-71391-7 paperback Cambridge University Press has no responsibility for the persistence or accuracy of urls for external or third-party internet websites referred to in this publication, and does not guarantee that any content on such websites is, or will remain, accurate or appropriate. Every effort has been made in preparing this publication to provide accurate and up-to-date information which is in accord with accepted standards and practice at the time of publication. Although case histories are drawn from actual cases, every effort has been made to disguise the identities of the individuals involved. Nevertheless, the authors, editors and publishers can make no warranties that the information contained herein is totally free from error, not least because clinical standards are constantly changing through research and regulation. The authors, editors and publishers therefore disclaim all liability of direct or consequential damages resulting from the use of material contained in this publication. -

KOONTZ, Dean R(Ay)

KOONTZ, Dean R (ay) Geboren: Everett, Pennsylvania, USA, 9 juli 1945 Pseudoniemen: David Axton; Brian Coffey, Deanna Dwyer; K.R. Dwyer; John Hill; Leigh Nichols; Anthony North; Richard Paige; Owen West Opleiding: Shippensburg State College, Pennsylvania, B.A. engels, 1966 Carrière: werkte bij een federaal armoede-bestrijdings programma, 1966-1967; leraar engels op een high school, 1967-1969; full-time schrijver sedert 1969. Familie: getrouwd met Gerda Ann Cerra, 1966 Woont in Orange, Californië. (foto: Fantastic Fiction) Detective: Michael Tucker (o.ps. Brian Coffey) detective: Odd Thomas kan de doden zien en ziet in zijn dromen wat mensen te wachten staat. Odd Thomas: 1. Odd Thomas 2003 De gave 2004 Luitingh ook verschenen als filmeditie odt: Odd Tomas: De gave 2015 Luitingh 2. Forever Odd 2005 De vriendschap 2006 Luitingh 3. Brother Odd 2006 De broeder 2007 Luitingh 4. Odd Hours 2008 De ziener 2008 Luitingh 5. Odd Apocalypse 2012 De miljardair 2012 Luitingh 6. Deeply Odd 2013 De lifter 2013 Luitingh~Sijthoff 7. Saint Odd 2015 graphic novels: In Odd We Trust #12 2008 Odd Is on Our Side #13 2010 House of Odd #14 2012 novellas: 1. Odd Interlude Part One 2012 2. Odd Interlude Part Two 2012 3. Odd Interlude Part Three 2012 4. Odd Interlude 2012 Het motel 2013 Luitingh~Sijthoff omslag ondertitel: A Special Odd Thomas Adventure 5. You Are Destined to Be Together Forever 2014 omnibus: The Complete Thomas Odd Series 2016 bevat: Odd Thomas Forever Odd Brother Odd Odd Hours Odd Apocalypse Odd Interlude Deeply Odd Saint Odd andere crimetitels: -

False Memory, 2012, 751 Pages, Dean Koontz, 0345533291, 9780345533296, Random House LLC, 2012

False Memory, 2012, 751 pages, Dean Koontz, 0345533291, 9780345533296, Random House LLC, 2012 DOWNLOAD http://bit.ly/12ZIuyC http://goo.gl/RciKx http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/False_Memory NEW YORK TIMESBESTSELLER  No fan of Dean Koontz or of psychological suspense will want to miss this extraordinary novel of the human mind’s capacity to torment—and destroy—itself.  It’s a fear more paralyzing than falling. More terrifying than absolute darkness. More horrifying than anything you can imagine. It’s the one fear you cannot escape no matter where you run . no matter where you hide.  It’s the fear of yourself. It’s real. It can happen to you. And facing it can be deadly.  False Memory. Fear for your mind. DOWNLOAD http://goo.gl/RPq4p http://bit.ly/1iCYniY Odd Thomas , Dean Koontz, 2004, Fiction, 446 pages. Over the course of two days, Odd Thomas, his soulmate Stormy Llewellyn, and an assortment of allies make their way through a dark, terrifying world in which past and present. Odd Apocalypse , Dean Koontz, Jul 31, 2012, Fiction, 400 pages. The fifth Odd Thomas thriller from the master storyteller. Odd finds refuge at a rundown mansion, but soon discovers a frightening presence.. Whispers , Dean Koontz, Dec 6, 2012, Fiction, 386 pages. A beautiful woman scarred by a hateful past. A compassionate cop haunted by a childhood bruised by poverty. Violence brought them together. An unspeakable abomination may tear. Brother Odd An Odd Thomas Novel, Dean Koontz, Jun 29, 2007, Fiction, 384 pages. NEW YORK TIMES BESTSELLER BONUS: This edition contains an excerpt from Dean Koontz's The City. -

Recovering Memories of Stories

FORGOTTEN, BUT NOT GONE: RECOVERING MEMORIES OF EMOTIONAL STORIES A Thesis by JUSTIN DEAN HANDY Submitted to the Office of Graduate Studies of Texas A&M University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF SCIENCE December 2011 Major Subject: Psychology Forgotten, but Not Gone: Recovering Memories of Emotional Stories Copyright 2011 Justin Dean Handy FORGOTTEN, BUT NOT GONE: RECOVERING MEMORIES OF EMOTIONAL STORIES A Thesis by JUSTIN DEAN HANDY Submitted to the Office of Graduate Studies of Texas A&M University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF SCIENCE Approved by: Chair of Committee, Steven M. Smith Committee Members, Lisa Geraci Louis G. Tassinary Head of Department, Ludy T. Benjamin, Jr. December 2011 Major Subject: Psychology iii ABSTRACT Forgotten, but Not Gone: Recovering Memories of Emotional Stories. (December 2011) Justin Dean Handy, B.A., High Point University Chair of Advisory Committee: Dr. Steven M. Smith Laboratory methods for studying memory blocking and recovery include directed forgetting, retrieval-induced forgetting, and retrieval bias or memory blocking procedures. These methods primarily use word lists. For example, striking, reversible forgetting effects have been reported for both emotional (e.g., expletives) and non- emotional (e.g., tools) categorized lists of words. The present study examined forgetting and recovery of richer, more episodic materials. Participants studied a series of brief narrative passages varying in emotional intensity, such as a vignette involving torture or child abuse (emotional) vs. vignettes about cycling or insects (non-emotional). Free recall of the 1-word titles of the vignettes (e.g., Torture, Cyclist) showed a strong memory blocking effect, and cues from the stories on a subsequent cued recall test reversed the effect. -

Silent Corner Discussion Questions by Dean Koontz

Silent Corner Discussion Questions by Dean Koontz Author Bio: (from Fantastic Fiction & Dean Koontz website) Dean Koontz is acknowledged as one of today's most celebrated and successful writers. His books are published in 38 languages and he has sold over 500 million copies to date. Dean Koontz lives in Southern California with his wife, Gerda, their golden retriever, Elsa, and the enduring spirit of their goldens, Trixie and Anna. Characters: Jane Hawk – Former FBI agent. Used to provide investigative support for the FBI Behavioral Science Unit. Widowed four months ago. Her husband, Nick, was a Marine. They have a son, Travis (5). Her mother is deceased. Her father is a famous musician. Mr. Drood – The alias of the man/group threatening Jane and Travis. Name taken from “A Clockwork Orange.” Kipp Garner – Radburn’s partner/henchman who enjoys violence. John Harrow – Special Agent in Charge of the LA FBI office. Nick Hawk – Former Marine. Unexpectedly and uncharacteristically kills himself with a knife. Married to Jane Hawk. Booth Hendrickson – Works in the Department of Justice. Becomes Silverman’s handler after his infection. Randolph Kohl – Director of Homeland Security. Gwyneth Lambert – Widow. Her husband, Gordon, was a former marine Lieutenant General who committed suicide. David James Michael – On the board of the Gernsback institute (What if Conference). Inherited a fortune. Venture capitalist who funds high tech startups – Shenneck’s technology and Far Horizons. William Sterling Overton – Lawyer. Friend/works for Senneck. Member of Aspasia. Jimmy Radburn – Hacker/cracker extraordinaire. Thinks of himself as a cyberspace pirate. His real name is Robert Branwick. -

Bibliography of Reviews of the Works for Dean Koontz As Removed from the Manuscript of the Collectors Guide to Dean Koontz by Michael P

A (very incomplete) Bibliography of reviews of the works for Dean Koontz as removed from the manuscript of The Collectors Guide to Dean Koontz by Michael P. Sauers to be published by Cemetery Dance Publications in 2011 The story behind this document can be found @ http://www.travelinlibrarian.info/CGTDK/2010/08/12/review-removal/ After the Last Race by Dean R. Koontz Reviews Kirkus Reviews v42 Sept. 1, 1974 p961 Publisher’s Weekly v206 Sept. 23, 1974 p148 Library Journal v99 Oct. 1, 1974 p2505 NEW YORK TIME BOOK REVIEW Jan. 12,1975 p18 Best Sellers v34 Feb. 1, 1975 p498 Publisher’s Weekly v208 Nov. 17, 1975 p99 Anti-Man by Dean R. Koontz Reviews Luna Monthly 26/27:33 Jl/Aug 1971 -Evers, J. The Bad Place by Dean R. Koontz Reviews New York Times Feb. 08,1989 pC26 -McDowell, E. Kirkus Reviews v57 Nov. 1, 1989 p1551 Booklist v86 Nov. 15, 1989 p618 Publisher’s Weekly Nov. 24,1989 p59 -Steinberg, S. Library Journal v114 Dec 1989 p170 (2) -Annichiarico, Mark Connoisseur v219 Dec 1989 p40 -Sawhill, Ray Rave Reviews #22, Dec/Jan (1989/90) p71 -Frank A. LaPorto The Blood Review v1 #2, Jan 1990 p51 -Richard Wellgosh The Blood Review v1 #2, Jan 1990 p51 -Mark Grahm West Coast Review of Books v15 #3 1990 p29 Atlanta Journal-Constitution Jan 21 1990 sec N p8 -Janet Ward LA Times Book Review Jan. 21, 1990 p12 Boston Globe Jan 25 1990 p75 -Bob MacDonald San Francisco Chronicle Feb 4 1990 sec REV p6 -Leila Raim New York Times Book Review Feb. -

Grandiloquent Dictionary Third Edition

Grandiloquent Dictionary Third Edition C.S. Bird February 25, 2006 ii . c 2006, C.S. Bird and Associates First published in electronic form in December 1998. First published in paperback in June 1999. Second Printing, January 2003 Third Printing, January 2006 No part of this book may be reproduced in any form, including but not limited to electronic copies and photocopies, without the express written consent of the authors or any agent chosen by the authors. A abacinate - To blind by putting a hot copper basin near someone's eyes abcedarian - A person who teaches the alphabet abderian - given to incessant or idiotic laughter abecedarian - A person who is learning the alphabet abishag - A child born to a married man's mistress ablegate - A representative of the pope who assists in selecting cardinals abligurition - Excessive spending on food and drink ablutophobia - A fear of bathing abnormous - Something which is misshapen acarophobia - 1.A fear of insects acarophobia - 2.A fear of mites acarophobia - 3. A fear of small things, especially bugs acathasia - The habit of sitting down accidia - A feeling of being unable to think or act due to excessive sadness accipitrine - having a nose like a hawk's beak accoucheur - A man who assists in delivering babies, usually at home accubation - The practice of eating or drinking while lying down accubitus - Sharing a bed for sleeping only aceldama - A blood soaked battlefield acerbophobia - See acerophobia acerophobia - The fear of sourness achluophobia - A fear of darkness or of the night acosmist -

RAR AVANT LAFT 19.Pdf

LOS T AND F 0 U N D TI " ES No. 19, May 1986 S3 Al Ackerman S. Gustav Hagglund John Adams wf. heineman Ivan ArgUelles Bob Heman Vittore Baroni Crag Hill C. Mehrl Bennett G. Huth John Bennett Charles L. Johnson John M. Bennett Snow White Jung William E. Bennett M. Kettner Bliss Blood Mark Laba Ernest Noyes Brookings John Wingo long John Buckner Alexander Martin Paula Claire Patrick McKinnon Robin Crozier Mike Murphy jwcurry Nico Hal J. Daniel III B. Z. Niditch William Virgil Davis Bern Porter Michael Dec Jerry Ratch Greg Evason H. Michael Sanders Charles Henri Ford Andrew Savage Joachim Frank Reepak Shakya Loss Pequeno Glazier Bill Shields Jim Grabill Stacey Sollfrey David Greenberger Paul Weinman Andrew J. Grossman Irving Weiss Jake Berry Vittore Baroni Cover by Vittore Baroni Thanks to David Greenberger and the DUPLEX PLANET for the Brookings poem and the spit interview. Thanks to The Harl Vincent Memorial Foundation for a grant helping to make this issue possible. DENTAL PROTECTION Apologies to jwcurry and Mark Laba whose poems in this issue should have been in the last issue Women wrap their mouths around men like pogo sticks but were left out by the Editor whose head was to feel what a vibration is like full of spit. from the inside in John M. Bennett, Editor stretching their protection around their mouths forming the curve of a plastic sealer that reminds them that smiling is their only way of knowing something is pulling their lips (SHIRKING) from the inside out letting the top lip act as the external ~ that pushes the whole face With the support of into the plastic the Ohio Arts Council C1C making sure the curve is too narrow for them to widen their eyes into Subscription: $10 for 5 numbers. -

Winter Moon Ebook

WINTER MOON PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Dean R Koontz | 472 pages | 31 Jul 2012 | Random House USA Inc | 9780345533470 | English | New York, United States Winter Moon PDF Book Jack is picked up by a snowplow driver, Harlan Moffit, and sees the house on fire when they pull in the driveway. Necessary cookies are absolutely essential for the website to function properly. I have loved all of Nicole Poole's work she just makes each voice to the characters distinct. She becomes addicted to the game because she is unable to leave her hospital room and sees this as her only way to escape reality and make friends. What do I need to see a meteor shower? He sees beauty Take advantage of a dark night sky to see the planets. A cool March wind sprang up. This solstice is the summer solstice in the Northern Hemisphere, where it is the longest day of the year. You wouldn't believe the mess they make, disgusting, things I'd be embarrassed to talk about. Use the Interactive Night Sky Map to find out what planets are visible tonight and where. Also known as the autumnal fall equinox in the Northern Hemisphere, the September Equinox is considered by many as the first day of fall. A common explanation is that Colonial Americans adopted many of the Native American names and incorporated them into the modern calendar. We read about the love of family but there is the open story of Lakota and possibly Melody? Special talent is lagging at the right moment before someone or something attacks him and somehow his enemies end up defeated while he remains unharmed. -

Kamus-Psikologi.Pdf

Dictionary of Psychological Testing, Assessment and Treatment by the same author The Psychology of Ageing An Introduction 4th edition ISBN 978 1 8431 0426 1 An Asperger Dictionary of Everyday Expressions 2nd edition ISBN 978 1 84310 518 3 Dictionary of Cognitive Psychology ISBN 978 1 85302 148 0 Dictionary of Developmental Psychology ISBN 978 1 85302 146 6 Key Ideas in Psychology ISBN 978 1 85302 359 0 Dictionary of Psychological Testing, Assessment and Treatment Second Edition Ian Stuart-Hamilton Jessica Kingsley Publishers London and Philadelphia First edition published in 1995 Paperback edition published in 1996 This edition published in 2007 by Jessica Kingsley Publishers 116 Pentonville Road London N1 9JB, UK and 400 Market Street, Suite 400 Philadelphia, PA 19106, USA www.jkp.com Copyright © Ian Stuart-Hamilton 1995, 1996, 2007 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced in any material form (including photocopying or storing it in any medium by electronic means and whether or not transiently or incidentally to some other use of this publication) without the written permission of the copyright owner except in accordance with the provisions of the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988 or under the terms of a licence issued by the Copyright Licensing Agency Ltd, 90 Tottenham Court Road, London, England W1T 4LP. Applications for the copyright owner’s written permission to reproduce any part of this publication should be addressed to the publisher. Warning: The doing of an unauthorised act in relation to a copyright work may result in both a civil claim for damages and criminal prosecution. -

2018 Mizmor Anthology Manuscript

Mizmor Anthology 2018 Poetry Collection www.PoeticaPublishing. com Managing Editor Michal Mahgerefteh Visiting Editors David King Daniel Pravda Rabbi Dr. Israel Zoberman Cover Art: “Vineyard” Digital Painting Michal Mahgerefteh www.Mitak-Art.com All rights reserved. The writers published in this edition retain complete copyright ownership for their own work. No part of this book may be used or reproduced in any form without prior written permission from the copyright owner or publisher, except for reviewers who wish to quote brief passages. Copyright First Edition 2019. Anthology Publisher: Poetica Publishing Company www.PoeticaPublishing.com 5215 Colley Ave #138 Norfolk, Virginia 23508 ©2019 Poetica Magazine ISSN: 1541-1923 (2002-2019) Printed in the United States of America. This edition is sponsored by Ben and Michal Mahgerefteh in memory of their mothers Bibi and Varda z’l Contents Yong Takahashi, CONTAINMENT 1 J. R. Solonche, I WANTED TO MAKE A COVENANT WITH THE WIND 2 Adrian Schnall, MOTHER WOULDN’T LISTEN TO WAGNER 4 Anna Wysocki-Cronan, AUSCHWITZ: A WALK 6 Leonard Orr, FLEEING RAN IN THE FAMILY 8 Sarah Brown Weitzman, CAIN FIRST BORN 10 Sarah Brown Weitzman, HOME 12 Sarah Brown Weitzman, A HISTORY OF BLUE 14 Sarah Brown Weitzman, THEY WHO ONCE 17 Sarah Brown Weitzman, THE STONE READER 18 Richard Schiffman, SUNDRY HUNGERS 20 Richard Schiffman, PASSOVER 21 Wilderness Sarchild, APPLE PIE 22 Joanne Jagoda, WELCOMING THE SHABBATH BRIDE 24 Stephen Nielsen, MENORAH 25 Steven Sher, OUTSIDE THE CENTRAL BUS STATION IN JERUSALEM 26 Steven -

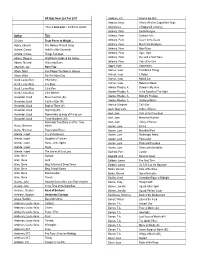

AR Quiz Short List Fall 2011 Titles in Bold Print = Nonfiction Section

AR Quiz Short List Fall 2011 Andrews, V.C. Pearl in the Mist Angelou, Maya I Know Why the Caged Bird Sings Titles in bold print = nonfiction section Anonymous It Happened to Nancy Anthony, Piers Castle Roogna Author Title Anthony, Piers Centaur Aisle 50 Cent From Pieces to Weight… Anthony, Piers Golem in the Gears Abbey, Edward The Monkey Wrench Gang Anthony, Piers Man From Mundania Achebe, Chinua Anthills of the Savannah Anthony, Piers Night Mare Achebe, Chinua Things Fall Apart Anthony, Piers Ogre, Ogre Adams, Douglas Hitchhiker's Guide to the Galaxy Anthony, Piers Roc and a Hard Place Adams, Richard Watership Down Anthony, Piers Vale of the Vole Adamson, Joy Born Free Appelt, Kathi Underneath Albom, Mitch Five People You Meet in Heaven Asimov, Isaac Foundation Trilogy Albom, Mitch For One More Day Asimov, Isaac I, Robot Alcott, Louisa May Inheritance Asimov, Isaac Naked Sun Alcott, Louisa May Jo's Boys Asimov, Isaac Robots of Dawn Alcott, Louisa May Little Men Atwater-Rhodes, A. Demon in My View Alcott, Louisa May Little Women Atwater-Rhodes, A. In the Forests of The Night Alexander, Lloyd Black Cauldron (#2) Atwater-Rhodes, A. Midnight Predator Alexander, Lloyd Castle of Llyr (#3) Atwater-Rhodes, A. Shattered Mirror Alexander, Lloyd Book of Three (#1) Atwood, Margaret Cat's Eye Alexander, Lloyd High King (#5) Auch, Mary Jane Ashes of Roses Alexander, Lloyd Remarkable Journey of Prince Jen Auel, Jean Clan of the Cave Bear Alexander, Lloyd Taran Wanderer (#4) Auel, Jean Mammoth Hunters Absolutely True Diary of a Part -Time Auel, Jean