C H a P T E R N Y

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Broken Fences

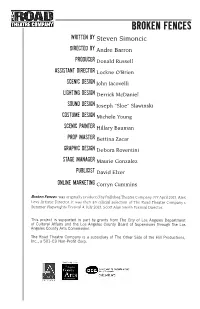

BROKEN FENCES WRITTEN BY Steven Simoncic DIRECTED BY Andre Barron PRODUCER Donald Russell ASSISTANT DIRECTOR Lockne O’Brien SCENIC DESIGN John Iacovelli LIGHTING DESIGN Derrick McDaniel SOUND DESIGN Joseph “Sloe” Slawinski COSTUME DESIGN Michele Young SCENIC PAINTER Hillary Bauman PROP MASTER Bettina Zacar GRAPHIC DESIGN Debora Roventini STAGE MANAGER Maurie Gonzalez PUBLICIST David Elzer ONLINE MARKETING Corryn Cummins Broken Fences was originally produced by Ballybeg Theatre Company, NY April 2013, Alex Levy Artistic Director. It was then an official selection of The Road Theatre Company’s Summer Playwrights Festival 4, July 2013, Scott Alan Smith Festival Director. This project is supported in part by grants from The City of Los Angeles Department of Cultural Affairs and the Los Angeles County Board of Supervisors through the Los Angeles County Arts Commission. The Road Theatre Company is a subsidiary of The Other Side of the Hill Productions, Inc., a 501-C3 Non-Profit Corp. head_a1 A NOTE FROM THE ARTISTICHEAD_A2 DIRECTORS Deartext Road block. Patrons: styles Whether vary. this is your first visit to the Road or you are a returning part of our theatre family, we welcome you to another exciting series of Road Repertory. This exciting experiment of running two shows at a time on a convertible set was such a hit for us last season, we decided to do it again. Thanks to the Summer Playwrights Festival, the Road has found itself with a true embarrassment of riches when it comes to new plays, and this first duo exemplifies our mission at its finest. Steven Simoncic’s exciting and provocative Broken Fences was a part of the Festival several summers ago, and we felt the time was right to present it to you now, directed by Andre Barron, who guided our hit production of Sharr White’s The Other Place last season. -

What's New in the Arts

THE SAN DIEGO UNION-TRIBUNE SUNDAY• MARCH 28, 2021 E9 V IRTUALLY SPEAKING UCTV University of California Televi- sion (UCTV) is making a host of videos available on its website (uctv.tv/life-of-the-mind) during What’s new this period of social distancing. Among them, with descriptions ARMCHAIR TRAVEL courtesy of UCTV (text written by the UCTV staff): in DININGthe arts “Tales of Human History Told by Neanderthal and Denisovan DNA”: It’s well known that as Celebrating 50 years of Queen with 50 weeks’ worth of free clips anatomically modern humans THEATER dispersed out of Africa, they BY DAVID L. CODDON encountered and mated with The film adaptation of playwright other hominins such as Neander- Kemp Powers’ “One Night in thals and Denisovans. The ability e’ve all got a list of those bands we wish we’d seen in concert but never did. Miami,” for which he wrote the to identify and excavate extinct screenplay, earned Powers an At the top of mine would be Queen with Freddie Mercury. hominin DNA from the genomes Oscar nomination. Having really It’s hard to believe it’ll be 30 years this November since the passing of of contemporary individuals enjoyed it, I looked forward Mercury, he of arguably the most distinctive voice in rock ’n’ roll history. reveals considerable information eagerly to streaming a staged W about human history and how The 2018 biopic “Bohemian Rhapsody” was a diverting reminder of Mercury’s talent, reading of Powers’ new play those encounters with Neander- “Christa McAuliffe’s Eyes Were but a new clips show on Queen’s official YouTube Channel honoring the group’s 50-year thals and Denisovans shaped the Blue.” anniversary is a gift for fans that will keep on giving — for 50 weeks. -

TORCH Spring 09.Qxd

TORCH • Spring 2009 1 TORCH magazine is the official publication of Lee LEE UNIVERSITY University, Cleveland, Tennessee. It is intended to inform, educate and give SPRING 2009 insight to alumni, parents VOL. 51, NO. 1 and friends of the university. TORCH It is published quarterly and mailed free to all alumni of the university. Other 4 Soon to be History 16 $400,000 + subscriptions are available As preparations are made for its razing this Thanks to all alumni who pitched in to help the by calling the alumni office summer, science alumni share their reflections alumni office top yet another milestone in the at 423-614-8316. on a building which steered their academic Annual Alumni Fund. TORCH MAGAZINE destiny while a student at Lee. Cameron Fisher, editor 22 A National Championship … and George Starr, sports editor 11 On the Honor Roll … Again Much More Bob Fisher, graphic designer Lee’s service learning benevolence program Since the Lee women’s soccer team won nation- CONTRIBUTING WRITERS continues to gain recognition, rubbing shoul- als, the honors, awards and recognitions for the Kelly Bridgeman, Michelle Boll- ders and even outshining Ivy League programs. team and the university continue to roll in. man, Brian Conn, Paul Conn, Rebekah Eble, Cameron Fisher, Whitney Hemphill, Harrison Keely, Christie Kleinmann, Ryan McDermott, George Starr, Joyanna Weber. PHOTOGRAPHERS Brian Conn, Cameron Fisher, Whitney Hemphill, Andrew Millar, George Starr, Sherry Vincent, Mike Wesson. TORCH welcomes and encourages Letters to the Editor, Who’s Where entries and other inquiries for consideration of publication. Submissions should be accompanied by the name, address, phone number and e-mail address of the sender. -

Adopted Budget

KNOX COUNTY TENNESSEE ADOPTED BUDGET Proposed Hardin Valley High FISCAL YEAR 2006-2007 Michael R. Ragsdale County Mayor KNOX COUNTY, TENNESSEE Fiscal Year 2007 BUDGET “Delivering essential services to Knox County citizens, while building the economic base and related infrastructure needed to be competitive in the 21st century.” Executive Sponsors: Mike Ragsdale, County Mayor John Werner II, Sr. Finance Director Prepared by: John Troyer, Comptroller, Deputy Finance Director Ann Acuff, Accounting/Budget Manager Jack Blackburn, Budget Analyst Dora Compton, Chief Executive Assistant TABLE OF CONTENTS Introductory Section Office of the County Mayor Message------------------------------------------------------- 1 Major Initiatives ------------------------------------------------------------------------------- 2 State of the Community Speech-------------------------------------------------------------- 4 Local Economic Condition and Outlook-------------------------------------------------- 10 Roster of Publicly Elected Officials ------------------------------------------------------- 16 Government Structure/Financial Guidelines and Policies ------------------------------ 18 Basis for Budget Presentation-------------------------------------------------------------- 22 County Organizational Charts Citizens---------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- 27 Knox County Government------------------------------------------------------------------ 28 Budget Process Budget Planning Calendar ------------------------------------------------------------------ -

Delta Music Heritage Research Project - Part I

II’m’m GGoin’oin’ OOverver ’’nn OOl’l’ HHelenaelena Arkansas Delta Music Heritage Research Project - Part I Prepared for Department of Arkansas Heritage Delta Cultural Center Helena, Arkansas Helena-West Helena Prepared by Advertising and Promotion Commission Mudpuppy & Waterdog, Inc. Helena, Arkansas Versailles, Kentucky December 31, 2015 I’m Goin’ Over’ n Ol’ Helena . Delta Music Heritage Research Project Part I Prepared by Joseph E. Brent Maria Campbell Brent Mudpuppy & Waterdog, Inc. 129 Walnut Street Versailles, Kentucky 40383 Prepared for Katie Harrington, Director Department of Arkansas Heritage Delta Cultural Center 141 Cherry Street Helena, Arkansas 72342 Cathy Cunningham, Chairman Helena-West Helena Advertising and Promotion Commission PO Box 256 Helena, Arkansas 72342 December 31, 2015 Table of Contents Part I Acknowledgments ...............................................................................................................1 Introduction ........................................................................................................................3 Musical Heritage of the Arkansas Delta ............................................................................5 Blues Music in the Arkansas Delta ....................................................................................7 Blues Artists of the Arkansas Delta ....................................................................................37 Part II The Growth of Popular Music ...........................................................................................1 -

Grace Notes July & August 2021

Grace Notes July & August 2021 Our Mission Statement: To know Christ & make Christ known Grace Episcopal Church 106 Lowell St. Manchester, NH Illustration byFreshour Andrew Table of Contents Rector’s Reflection - Returning to Communal Worship ............ 3 A Beautiful Day in the Neighborhood! ...................................... 4 Manchester Pride 2021 ............................................................... 5 Drive-By Eucharist ..................................................................... 5 Getting To Know You : Shelley Kesselman - Part One ............. 6 Grace Church Book Group Update ............................................ 9 Garden Prayer and Outdoor Care Thank You .......................... 11 Too Big, or Not Too Big? Interesting Question ....................... 12 Steeple Repair Update .............................................................. 13 June Hybrid Worship ............................................................... 13 Thank You from CHAMPS ..................................................... 14 Thank You from Marlene ......................................................... 15 Congratulations to Andrew Freshour ....................................... 15 Congratulations to Elizabeth Cleveland ................................... 16 Congratulations Middle School Graduates .............................. 16 Congratulations to Mannix Muir .............................................. 17 Zachary Stagnaro at the Palace Theatre ................................... 17 Congratulations to Kaydance Lassonde -

BY Lee Rainie and Janna Anderson

FOR RELEASE JUNE 6, 2017 BY Lee Rainie and Janna Anderson FOR MEDIA OR OTHER INQUIRIES: Lee Rainie, Director, Internet, Science and Technology research Janna Anderson, Director, Imagining the Internet Center, Elon University Dana Page, Senior Communications Manager 202.419.4372 www.pewresearch.org RECOMMENDED CITATION Pew Research Center, June 2017, “The Internet of Things Connectivity Binge: What are the Implications?” Available at: http://www.pewinternet.org/2017/06/06/the- internet-of-things-connectivity-binge-what-are-the- implications/ 1 PEW RESEARCH CENTER About Pew Research Center Pew Research Center is a nonpartisan fact tank that informs the public about the issues, attitudes and trends shaping America and the world. It does not take policy positions. The center conducts public opinion polling, demographic research, content analysis and other data-driven social science research. It studies U.S. politics and policy; journalism and media; Internet, science and technology; religion and public life; Hispanic trends; global attitudes and trends; and U.S. social and demographic trends. All of the center’s reports are available at www.pewresearch.org. Pew Research Center is a subsidiary of The Pew Charitable Trusts, its primary funder. For this project, Pew Research Center worked with Elon University’s Imagining the Internet Center, which helped conceive the research, collect, and analyze the data. © Pew Research Center 2017 www.pewresearch.org 2 PEW RESEARCH CENTER The Internet of Things Connectivity Binge: What Are the Implications? Connection begets connection. In 1999, 18 years ago, when just 4% of the world’s population was online, Kevin Ashton coined the term Internet of Things, Neil Gershenfeld of MIT Media Lab wrote the book “When Things Start to Think,” and Neil Gross wrote in BusinessWeek: “In the next century, planet Earth will don an electronic skin. -

Through the Eye of a Needle

WORLD PREMIERE THROUGH THE EYE OF A NEEDLE WRITTEN BY Jami Brandli DIRECTED BY Ann Hearn PRODUCERS Mia Fraboni, Tracey Silver ASSISTANT DIRECTOR Tom Knickerbocker SCENIC DESIGN Pete Hickok LIGHTING DESIGN Derrick McDaniel COSTUME DESIGN Mary Jane Miller SOUND DESIGN David B. Marling PROPS Megan Moran & Christine Joëlle FOOD WRANGLER Samuel Martin Lewis STAGE MANAGER Maurie Gonzalez ASSITANT STAGE MANAGER Adam Duarte GRAPHIC DESIGNER Cece Tsou PUBLICIST David Elzer ONLINE MARKETING Kay Capasso MUSIC CONSULTANT Dimitris Mahlis MARTIAL ARTS CONSULTANT: High Key Fitness Karate Master Shaunt Benjamin DIALECT COACH Andrea Odinov Fuller Through the Eye of a Needle was developed through LAUNCH PAD Summer Reading Series at the University of California, Santa Barbara Department of Theatre and Dance in 2017, Risa Brainin, Director.Through the Eye of a Needle is presented by special arrangement with the Robert A. Freedman Dramatic Agency, Inc. This project is supported in part by grants from The City of Los Angeles Department of Cultural Affairs and the Los Angeles County Board of Supervisors through the Los Angeles County Arts Commission. The Road Theatre Company is a subsidiary of The Other Side of the Hill Productions, Inc., a 501-C3 Non-Profit Corp. head_a1 A NOTE FROM THE ARTISTICHEAD_A2 DIRECTORS Deartext Road block. Patrons, Welcomestyles vary. back to the third MainStage show of the Road Theatre’s 26th season. Following the very successful, much-discussed Ovation recommended world premiere of Sharr White’s Stupid Kid, we continued our journey into stories of young people in process, often challengingly so. From the back roads of Colorado, we moved to the heart of Brooklyn on Christmas Eve, and explored the complicated, tragic world of Anna Ziegler’s three bright 30-somethings in our record-selling A Delicate Ship, a production that moved audiences across age ranges, sensibilities and backgrounds, thanks to Ms. -

BY Lee Rainie and Janna Anderson

FOR RELEASE AUGUST 10, 2017 BY Lee Rainie and Janna Anderson FOR MEDIA OR OTHER INQUIRIES: Lee Rainie, Director, Internet, Science and Technology research Janna Anderson, Director, Imagining the Internet Center, Elon University Tom Caiazza, Communications Manager 202.419.4372 www.pewresearch.org RECOMMENDED CITATION Pew Research Center, August 2017, “The Fate of Online Trust in the Next Decade“ Available at: http://www.pewinternet.org/2017/08/10/the- fate-of-online-trust-in-the-next-decade/ 1 PEW RESEARCH CENTER About Pew Research Center Pew Research Center is a nonpartisan fact tank that informs the public about the issues, attitudes and trends shaping America and the world. It does not take policy positions. The center conducts public opinion polling, demographic research, content analysis and other data-driven social science research. It studies U.S. politics and policy; journalism and media; Internet, science and technology; religion and public life; Hispanic trends; global attitudes and trends; and U.S. social and demographic trends. All of the center’s reports are available at www.pewresearch.org. Pew Research Center is a subsidiary of The Pew Charitable Trusts, its primary funder. For this project, Pew Research Center worked with Elon University’s Imagining the Internet Center, which helped conceive the research, collect, and analyze the data. © Pew Research Center 2017 www.pewresearch.org 2 PEW RESEARCH CENTER The Fate of Online Trust in the Next Decade Trust is a social, economic and political binding agent. A vast research literature on trust and “social capital” documents the connections between trust and personal happiness, trust and other measures of well-being, trust and collective problem solving, trust and economic development and trust and social cohesion. -

Extensions of Remarks E739 EXTENSIONS of REMARKS

June 11, 2019 CONGRESSIONAL RECORD — Extensions of Remarks E739 EXTENSIONS OF REMARKS IN RECOGNITION OF DENVER EAST REMEMBERING THE LIFE AND RECOGNIZING COLONEL TIMOTHY HIGH SCHOOL’S ‘WE THE PEO- LEGACY OF MR. HOWELL BEGLE HOLMAN PLE’ NATIONAL FINALS FIRST PLACE WIN HON. DONALD S. BEYER, JR. HON. TRENT KELLY OF MISSISSIPPI OF VIRGINIA HON. DIANA DeGETTE IN THE HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES IN THE HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES OF COLORADO Tuesday, June 11, 2019 Tuesday, June 11, 2019 IN THE HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES Mr. KELLY of Mississippi. Madam Speaker, Tuesday, June 11, 2019 Mr. BEYER. Madam Speaker, I rise today to today I recognize Colonel Timothy Holman of ask the House of Representatives to join me the United States Army for his extraordinary Ms. DEGETTE. Madam Speaker, I rise in celebrating the exemplary life of Mr. Howell dedication and service to our Nation. Colonel today to congratulate Denver East High Begle—a veteran Army captain, lawyer, advo- Holman will soon transition from his current School on its first-place finish in the 2019 na- cate for R&B singers’ rights and my dear assignment as the Chief of the United States tional finals of the ‘We the People’ competition friend. Army House Liaison Division in the House of sponsored by the Center for Civic Education. Howell’s life was spent in service to his Representatives to the Deputy for the Army’s The students and teachers of the Denver East country and helping others. After receiving his Unity and Inclusion Office. High School team should feel exceptionally law degree from the University of Michigan in With an impressive and proven record of proud of this outstanding achievement.