Relevance of Graph Literacy in the Development of Patient-Centered

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Exploring Differences Among Student Populations During Climate Graph Reading Tasks: an Eye Tracking Study Rachel M

Journal of Astronomy & Earth Sciences Education – December 2018 Volume 5, Number 2 Exploring Differences Among Student Populations During Climate Graph Reading Tasks: An Eye Tracking Study Rachel M. Atkins, North Carolina State University, USA Karen S. McNeal, Auburn University, USA ABSTRACT Communicating climate information is challenging due to the interdisciplinary nature of the topic along with compounding cognitive and affective learning challenges. Graphs are a common representation used by scientists to communicate evidence of climate change. However, it is important to identify how and why individuals on the continuum of expertise navigate graphical data differently as this has implications for effective communication of this information. We collected and analyzed eye-tracking metrics of geoscience graduate students and novice undergraduate students while viewing graphs displaying climate information. Our findings indicate that during fact- extraction tasks, novice undergraduates focus proportionally more attention on the question, title and axes graph elements, whereas geoscience graduate students spend proportionally more time viewing and interpreting data. This same finding was enhanced during extrapolation tasks. Undergraduate novices were also more likely to describe general trends, while graduate students identified more specific patterns. Undergraduates who performed high on the pre-test measuring graphing skill, viewed graphs more similar to graduate students than their peers who performed lower on the pre-test. Keywords: Geoscience Education Research; Geocognition; Eye-Tracking; Graph Reading he average temperature of our planet has increased 1.5 degrees F over the past 100 years and is projected to increase another 0.5 to 8.6 degrees F over the next century (U.S. Environmental Protection Agency, 2014). -

Vlat: Development of a Visualization Literacy Assessment Test 553

IEEE TRANSACTIONS ON VISUALIZATION AND COMPUTER GRAPHICS VOL. 23, NO. 1, JANUARY 2017 551 VLAT : Development of a Visualization Literacy Assessment Test Sukwon Lee, Sung-Hee Kim, and Bum Chul Kwon, Member, IEEE Abstract— The Information Visualization community has begun to pay attention to visualization literacy; however, researchers still lack instruments for measuring the visualization literacy of users. In order to address this gap, we systematically developed a visual- ization literacy assessment test (VLAT), especially for non-expert users in data visualization, by following the established procedure of test development in Psychological and Educational Measurement: (1) Test Blueprint Construction, (2) Test Item Generation, (3) Content Validity Evaluation, (4) Test Tryout and Item Analysis, (5) Test Item Selection, and (6) Reliability Evaluation. The VLAT con- sists of 12 data visualizations and 53 multiple-choice test items that cover eight data visualization tasks. The test items in the VLAT were evaluated with respect to their essentialness by five domain experts in Information Visualization and Visual Analytics (average content validity ratio = 0.66). The VLAT was also tried out on a sample of 191 test takers and showed high reliability (reliability coeffi- cient omega = 0.76). In addition, we demonstrated the relationship between users’ visualization literacy and aptitude for learning an unfamiliar visualization and showed that they had a fairly high positive relationship (correlation coefficient = 0.64). Finally, we discuss evidence for the validity of the VLAT and potential research areas that are related to the instrument. Index Terms—Visualization Literacy; Assessment Test; Instrument; Measurement; Aptitude; Education 1INTRODUCTION Data visualizations have become more popular and important as the dressing this gap is important because measurement results from the amount of available data increases, called data democratization. -

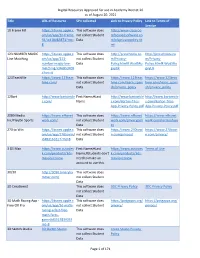

Digital Resources Approved for Use in Academy District 20 As Of

Digital Resources Approved for use in Academy District 20 as of August 20, 2021 Title URL of Resource SPII collected Link to Privacy Policy Link to Terms of Service 10 Frame Fill https://itunes.apple.c This software does http://www.classroo om/us/app/10-frame- not collect Student mfocusedsoftware.co fill/id418083871?mt= Data m/cfsprivacypolicy.ht 8 ml 123 NUMBER MAGIC https://itunes.apple.c This software does http://preschoolu.co http://preschoolu.co Line Matching om/us/app/123- not collect Student m/Privacy- m/Privacy- number-magic-line- Data Policy.html#.Wud5Ro Policy.html#.Wud5Ro matching/id46853409 gvyUk gvyUk 4?mt=8 123TeachMe https://www.123teac This software does https://www.123teac https://www.123teac hme.com/ not collect Student hme.com/learn_spani hme.com/learn_spani Data sh/privacy_policy sh/privacy_policy 12Bart http://www.bartontile First Name;#Last http://www.bartontile http://www.bartontile s.com/ Name s.com/Barton-Tiles- s.com/Barton-Tiles- App-Privacy-Policy.pdf App-Privacy-Policy.pdf 2080 Media https://www.nfhsnet This software does https://www.nfhsnet https://www.nfhsnet Inc/PlayOn Sports work.com/ not collect Student work.com/privacypoli work.com/termsofuse Data cy 270 to Win https://itunes.apple.c This software does https://www.270towi https://www.270towi om/us/app/270towin/ not collect Student n.com/privacy/ n.com/privacy/ id483161617?mt=8 Data 3 DS Max https://www.autodes First Name;#Last https://www.autodes Terms of Use k.com/products/3ds- Name;#Students don't k.com/products/3ds- max/overview need to make an max/overview account to use this. -

What Do Teachers Know and Want to Know About Special Education?

What Do Teachers Know and Want to Know About Special Education? First presenter: Angelique Aitken, University of Nebraska-Lincoln ([email protected]) Poster Abstract: Purpose The Council for Exceptional Children Professional Standards require that special education teachers have an understanding of the relevant special education laws and policies, which influence educating their students (CEC, 2015). Not only does a special educator provide academic, behavioral, and social skills instruction in accordance with their students' legally enforceable individualized education program (IEP) but federal and state laws (e.g., IDEA; 20 U.S.C. §§1400) have created compliance mechanisms that have intertwined legal topics with educating students. Furthermore, both parents and school administrators have reported that teachers are parents' primary source of special education information (Authors, under review and in preparation). Thus, it is important to understand teachers' knowledge of special education topics and processes. Method A convenience sample of 142 special education teachers across 16 states completed The Teacher Knowledge and Resources in Special Education (TKRSE) web-based survey. The TKRSE is comprised of 52 items across five domains and seven demographic items. The Accessibility of Resources domain had two items (e.g., Overall, how available are special education resources) rated on a 5-point Likert-type scale. Seventeen items (e.g., currently, how confident that you understand manifestation determination) were included in the Confidence in Special Education Topics domain and were each rated on a 4- point Likert-type scale. In the Areas of Desired Additional Knowledge domain, teachers were asked to identify the top topics that teachers would like to learn more about (e.g., Please identify the top three [special education law] topics you would like to learn more about). -

Graphing Literacy in a Seventh Grade Science Classroom

California State University, Monterey Bay Digital Commons @ CSUMB Capstone Projects and Master's Theses Capstone Projects and Master's Theses Spring 2021 Graphing Literacy in a Seventh Grade Science Classroom Tersiphone-Sheryll S. Hahn Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.csumb.edu/caps_thes_all This Master's Thesis (Open Access) is brought to you for free and open access by the Capstone Projects and Master's Theses at Digital Commons @ CSUMB. It has been accepted for inclusion in Capstone Projects and Master's Theses by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ CSUMB. For more information, please contact [email protected]. GRAPHING LITERACY IN SCIENCE CLASSROOMS 1 Graphing Literacy in a Seventh Grade Science Classroom Tersiphone-Sheryll S. Hahn Thesis Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts in Education California State University, Monterey Bay May 2021 ©2021 by Tersiphone-Sheryll Hahn. All Rights Reserved GRAPHING LITERACY IN SCIENCE CLASSROOMS 2 Graphing Literacy in a Seventh Grade Science Classroom Tersiphone-Sheryll S. Hahn APPROVED BY THE GRADUATE ADVISORY COMMITTEE __________________________________________________ Kerrie Chitwood, Ph.D. Advisor and Program Coordinator, Master of Arts in Education __________________________________________________ Wesley Henry, Ph.D. Advisor and Program Co-Coordinator, Master of Arts in Education __________________________________________________ Erin Ramirez, Ph.D. Advisor, Master of Arts in Education __________________________________________________ Daniel Shapiro, Ph.D. Interim Associate Vice President Academic Programs and Dean of Undergraduate & Graduate Studies GRAPHING LITERACY IN SCIENCE CLASSROOMS 1 Abstract Graphing literacy is an essential skill in processing and developing scientific understanding; however, students graduating from secondary science education do not exhibit the proper skills to be graphing literate. -

Tweet Archive on #Sharp17 from 5/3/2017

Tweet Archive on #sharp17 From 5/3/2017 - 7/1/2017 kamaslak: All you wanted to know and didn't know you wanted to know about technology of the books #SHARP17 https://t.co/YAolG4OZiw 5/3/2017 8:19:19 AM DHInstitute: Coming to #dhsi2017, #SHARP17 & interested in the \m/etal music community? (conf. w concert Friday; ask us for tix!) https://t.co/1pJsVwZI2S 5/3/2017 2:47:40 PM SHARP2017: RT @DHInstitute: Coming to #dhsi2017, #SHARP17 & interested in the \m/etal music community? (conf. w concert Friday; ask us for tix!) https… 5/3/2017 3:54:04 PM PaulaJohanson: @AlyssaA_DHSI Is it okay to #SHARP17 people to attend our two #dhsiknits workshops on June 4 and June 11? 5/3/2017 5:58:42 PM bookhistories: Less than one month to go until #SHARP17! @SHARP2017 @sharpicecream 5/11/2017 9:54:30 PM lesliehowsam: RT @bookhistories: Less than one month to go until #SHARP17! @SHARP2017 @sharpicecream 5/12/2017 1:53:42 PM mulcare: Gah! If only it were possible to be in two places at the same time. #SHARP17 will be great, I'm sure, but will it b… https://t.co/ADgRuHB7dD 5/16/2017 7:05:44 PM SHARP2017: Ahoy! We have posted the detailed program for #sharp17: https://t.co/rveaXXn4eF 5/18/2017 12:42:59 AM TradeCardCarl: RT @SHARP2017: Ahoy! We have posted the detailed program for #sharp17: https://t.co/rveaXXn4eF 5/18/2017 1:10:30 AM amandalastoria: #SHARP17 conference incl 2 presentations on Alice in Wonderland: @MichaelHancher on Tenniel and me on #LewisCarroll… https://t.co/HTh9eKt4bs 5/18/2017 2:35:10 AM james_minter: RT @amandalastoria: #SHARP17 conference incl 2 presentations on Alice in Wonderland: @MichaelHancher on Tenniel and me on #LewisCarroll. -

Discourses Of

“ABOUT AVERAGE” A PRAGMATIC INQUIRY INTO SCHOOL PRINCIPALS’ MEANINGS FOR A STATISTICAL CONCEPT IN INSTRUCTIONAL LEADERSHIP A Thesis Submitted to the Faculty of Graduate Studies and Research In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Education University of Regina by Darryl Milburn Hunter Regina, Saskatchewan April 2014 Copyright 2014: Darryl M. Hunter UNIVERSITY OF REGINA FACULTY OF GRADUATE STUDIES AND RESEARCH SUPERVISORY AND EXAMINING COMMITTEE Darryl Milburn Hunter, candidate for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Education, has presented a thesis titled, “About Average” A Pragmatic Inquiry into School Principals’ Meanings for a Statistical Concept in Instructional Leadership, in an oral examination held on April 1, 2014. The following committee members have found the thesis acceptable in form and content, and that the candidate demonstrated satisfactory knowledge of the subject material. External Examiner: *Dr. Jerald Paquette, Professor Emeritus, University of Western Ontario Supervisor: Dr. William R. Dolmage, Educational Administration Committee Member: Dr. Ronald Martin, Educational Psychology Committee Member: **Dr. Larry Steeves, Educational Administration Committee Member: Dr. Katherine Arbuthnott, Department of Psychology Chair of Defense: Dr. Ronald Camp, Kenneth Levene Graduate School *via SKYPE **via Teleconference Abstract This mixed methods, sequential, exploratory study addresses the problem, “How significant are statistical representations of ‘average student achievement’ for school administrators as instructional leaders?” Both phases of the study were designed within Charles Sanders Peirce’s pragmatic theory of interpretation. In the first, phenomenological phase, 10 Saskatchewan school principals were each interviewed three times and invited to read aloud three different student achievement reports. Principals generally held a “centre-of-balance” conception for the average, which related to perspectives deriving from their organizational position. -

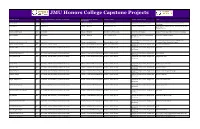

JMU Honors College Capstone Projects

JMU Honors College Capstone Projects Student Name Year Department (Where Capstone Completed) College (Where Capstone Advisor Name Advisor Classification Title Completed) Jin, Jing Jing 2015 Accounting College of Business Sandra Cereola, Ph.D. Associate Professor of Accounting Cybersecurity Disclosure Effectiveness on Public Companies Jones, Maria 2017 Accounting College of Business Luis Betancourt, Ph.D. Professor of Accounting The Expanded Auditor's Report: A Case Study From the United Kingdom Catania, Luke Francis 2018 Accounting College of Business Timothy J. Louwers, Ph.D. Professor of Accounting Frank J. Wilson: The Father of Forensic Accounting Aboite, Saleem 2019 Accounting College of Business Paul L. Raston, Ph.D. Assistant Professor of Chemistry and The P.A.L. Program Initiative Biochemistry Associate Professor of Sociology and The Archaeological Investigation of The Fannie Brauckmann, Katherine Nicole 2020 Anthropology College of Arts and Letters Dennis B. Blanton, Ph.D. Anthropology Thompson House, Greenville, Virginia Linder, Austen Coffman 2018 Art, Design, and Art History College of Visual and Performing Arts Richard D. Hilliard, M.F.A Associate Professor of Art, Design, and A World of Possiblilities Art History Chandler, Maya 2017 Art, Design, and Art History/Architectural Design College of Visual and Performing Arts Evelyn C. Tickle, M.Arch. Assistant Professor of Art, Design, and Wal-seum Art History Dunnenberger, Emilie E. 2017 Art, Design, and Art History/Architectural Design College of Visual and Performing Arts Evelyn C. Tickle, M.Arch. Assistant Professor of Art, Design, and The FARMacy Art History Faber, Kimberly M. 2017 Art, Design, and Art History/Architectural Design College of Visual and Performing Arts Evelyn C. -

Dyscalculia in Higher Education

DYSCALCULIA IN HIGHER EDUCATION By Simon Drew A Doctoral Thesis Submitted for the award of Doctor of Philosophy at Loughborough University September 2015 © Simon Drew 2015 Sisyphus by Lacie Cummings Abstract This research study provides an insight into the experiences of dyscalculic students in higher education (HE). It explores the nature of dyscalculia from the student perspective, adopting a theoretical framework of the social model of disability combined with socio-cultural theory. This study was not aimed at understanding the neurological reasons for dyscalculia, but focussed on the social effects of being dyscalculic and how society can help support dyscalculic students within an HE context. The study’s primary data collection method was 14 semi-structured interviews with officially identified dyscalculic students who were currently, or had been recently, studying in higher education in the UK. A participant selection method was utilised using a network of national learning support practitioners due to the limited number of participants available. A secondary data collection method involved reflective learning support sessions with two students. Data were collected across four research areas: the identification process, HE mathematics, learning support and categorisations of dyscalculia. A fifth area of fitness to practise could not be examined in any depth due to the lack of relevant participants, but the emerging data clearly pinpointed this as a significant area of political importance and identified a need for further research. A framework of five categories of dyscalculic HE student was used for data analysis. Participants who aligned with these categories tended to describe differing experiences or coping behaviours within each of the research areas. -

Practitioner Perception of the Implementation of Evidence-Based

PRACTITIONER PERCEPTION OF THE IMPLEMENTATION OF EVIDENCE-BASED PRACTICES IN THE SPECIAL EDUCATION CLASSROOM: A CASE STUDY by Jolene G. Swezey Liberty University A Dissertation Presented in Partial Fulfillment Of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy Liberty University 2021 2 PRACTITIONER PERCEPTION OF THE IMPLEMENTATION OF EVIDENCE-BASED PRACTICES IN THE SPECIAL EDUCATION CLASSROOM: A CASE STUDY by Jolene Gail Swezey A Dissertation Presented in Partial Fulfillment Of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy Liberty University, Lynchburg, VA 2021 APPROVED BY: Andrea P. Beam, EdD, Committee Chair James L. Eller, EdD, Committee Member 3 ABSTRACT The purpose of this qualitative instrumental case study was to identify factors that inform the decision-making process of 11 special education practitioners for the implementation of evidence-based practices in the classroom at Central Combined School (pseudonym). The theoretical framework for this study is Lipsky’s street-level bureaucracy theory. Street-level bureaucracy theory states that social services workers use discretion to administer required policies. Understanding how special educators act as street-level bureaucrats will provide new insights into teacher perception of the decision-making process for implementing evidence-based practices. The central research question asked, What are the factors that inform the decision- making process for special education practitioners for the implementation of evidence-based practices in the classroom? Data were collected using individual interviews, an online focus group, and documents/archival records. Data analysis consisted of categorical aggregation, development of naturalistic generalizations, and development of themes. Five themes developed from the research of this study: collaboration, expectations, environment, individualization, and training. -

TEACHER INTERPRETATION and APPLICATION of GRAPHED BEHAVIORAL DATA THROUGHOUT the RTI PROCESS by COLLEEN PATRICIA ANN BELMONTE

TEACHER INTERPRETATION AND APPLICATION OF GRAPHED BEHAVIORAL DATA THROUGHOUT THE RTI PROCESS By COLLEEN PATRICIA ANN BELMONTE A dissertation submitted to the School of Graduate Studies Rutgers, The State University of New Jersey In partial fulfillment of the requirements For the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Graduate Program in Education Written under the direction of Judith R. Harrison And approved by _____________________________________ _____________________________________ _____________________________________ _____________________________________ New Brunswick, New Jersey May, 2020 © 2020 Colleen Patricia Ann Belmonte ALL RIGHTS RESERVED ABSTRACT OF THE DISSERTATION Teacher Interpretation and Application of Graphed Behavioral Data Throughout the RTI Process By COLLEEN PATRICIA ANN BELMONTE Dissertation Director: Judith R. Harrison Students with or at-risk of High Incidence Disabilities (HID) experience a multitude of negative outcomes. To intervene early, many schools have elected to implement evidence-based practices within Response to Intervention (RTI). RTI targets the academic and behavioral progress of students deemed “at risk” for HID with increasingly intensive interventions. Throughout the RTI process, teachers play a critical role in data-based decision-making by collecting, interpreting, and applying behavioral data. However, very limited research has explored teacher ability, confidence, or usefulness to engage in this role. As such, the purpose of this study was to explore pre-service and in-service teachers’ ability, confidence, willingness, and perceived usefulness to interpret and apply behavioral data before and after a brief behavior analytic training titled “Collecting, Interpreting, and Applying Graphed Behavioral Data” (CIA-GBD), and the factors that influenced each outcome. One hundred and one participants completed a survey and 24 participants attended CIA-GBD. -

Does Face Orientation Affect the Perception of a Model and The

ASSOCIATION FOR CONSUMER RESEARCH Labovitz School of Business & Economics, University of Minnesota Duluth, 11 E. Superior Street, Suite 210, Duluth, MN 55802 Does Face Orientation Affect the Perception of a Model and the Evaluation of Advertised Product? Jaewoo Park, Musashi University, Japan Charles Spence, University of Oxford, UK Hiroaki Ishii, Seikei University, Japan Taku Togawa, Chiba University of Commerce, Japan [to cite]: Jaewoo Park, Charles Spence, Hiroaki Ishii, and Taku Togawa (2018) ,"Does Face Orientation Affect the Perception of a Model and the Evaluation of Advertised Product? ", in E - European Advances in Consumer Research Volume 11, eds. Maggie Geuens, Mario Pandelaere, and Michel Tuan Pham, Iris Vermeir, Duluth, MN : Association for Consumer Research, Pages: 35-29. [url]: http://www.acrwebsite.org/volumes/1700125/volumes/v11e/E-11 [copyright notice]: This work is copyrighted by The Association for Consumer Research. For permission to copy or use this work in whole or in part, please contact the Copyright Clearance Center at http://www.copyright.com/. Competitive Papers—Full Does Face Orientation Affect the Perception of a Model and the Evaluation of Advertised Product? Jaewoo Park, Musashi University, Japan Charles Spence, University of Oxford, UK Hiroaki Ishii, Seikei University, Japan Taku Togawa, Chiba University of Commerce, Japan ABSTRACT in the viewer’s left visual field, tend to be more easily recognized We report two experiments designed to demonstrate that a left- (Siéroff 2001; Yamamoto et al. 2005). For instance, Yamamoto et ward (vs. rightward) facing model’s face increases the perceived al. had their participants match either a left or right oblique view of trustworthiness of a model and subsequently the increased trustwor- familiar faces (e.g., a portrait of Gandhi) with names presented either thiness positively affect the evaluation of advertised products.